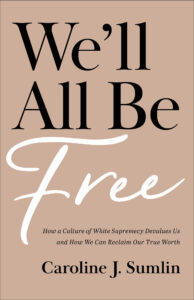

Many of us battle for self-worth in a world that is constantly bombarding us with messages that we are not enough. But author Caroline Sumlin argues that the enemy we are fighting is not just our own thoughts, but the insidious nature of white supremacy and the ways it impacts our society. UrbanFaith Editor Allen Reynolds interviewed influencer and author Caroline Sumlin about her new book We’ll All Be Free which confronts white supremacy’s assault on our self worth no matter what our background is, and shares ways we can liberate ourselves, each other, and seek healing. The book is available everywhere. The full interview is above, excerpts below have been edited for clarity and length. More about the book is below.

———————–

Allen

Hello, Urban Faith. It is a joy and a pleasure to be with just an awesome person someone who I’ve known for a long time who is doing work as an Instagram influencer as an author now that is Caroline Sumlin. And she has written a new book, We’ll All Be Free about dismantling white supremacy talking about self-worth. Why is it that you think it’s important that we deal with these difficult and tough issues?

Caroline

I think we can see the impacts of not having the tough conversations on our society. Even taking white supremacy aside, when we talk about going to therapy or we talk about dealing with mental health, we talk about trauma. We talk about those tough things. One of the most basic ways that parents sometimes explain emotions to children… is that they’re like farts. Kids don’t have any inhibitions to keep things in because they know it feels good to let out the burp, to pass gas, to cry, to get angry, to stomp our feet, right? They live and then guess what happens? They feel better because they release that stuff. As adults, we are conditioned to keep things inside, to be ashamed of it, to be ashamed of our humanity. And then what happens? The anger happens, right? The crippling and debilitating mental health [issues] happen. I could go on to name things. I mean, I even think the rise in gun violence, all of that is connected to the fact that we are not dealing with what’s going on inside, both individually, but also systemically. The culture we have created has magnified a society of people that are walking around with a lot of anger, with a lot of hurt, with a lot of unworthiness that they don’t realize is going on. Then we wonder why we see what we see in society. And I understand that people would also argue well having the conversations can also lead to “division.” And I would argue back that the reason why we see division when we have these conversations is because we have been conditioned to be defensive. We’ve been conditioned to ignore certain things and as a result we haven’t been [healthy]… But that’s all the more reason to keep going and to keep fighting and say, “Hey, we can get healthy. It takes work.” You know, no one goes to therapy and comes out smiling every day. You’re going to go to therapy and you’re going to come out with tears. You’re going to come out with anger. You may have to process some things that may feel uncomfortable at first, but then the burden starts to lift off your shoulders and it does get better. I do believe in pushing and continuing to have the conversation. I do believe that there will be a positive ending, but sometimes the messy middle is just necessary.

Allen

You have that chapter on hustle culture and how that’s tied to white supremacy. Can you just talk a little bit about that?

Caroline

Yeah, absolutely. I have an entire chapter on this because it is one of the biggest ways that white supremacy culture shows up in our daily lives. Are the entire idea of the American dream and the message that we are given as young children that if you just work hard enough and you just go to college and you’ll be able to achieve this ideal life in America, you’ll be able to buy a house, you’ll be able to have your family, you’ll be able to afford certain things and you’ll have that American dream. Over time that American dream has become a lot higher, a lot narrower. It used to be that middle class and now it’s gone beyond that at this point because again with the white supremacy culture, the standard is always moving. But I wanted to make sure that the readers were able to understand again the roots in that. I wanted to look at where [this idea comes] from where we have to achieve to be worthy. What [is] the definition of achievement, what the definition of success is, where did that come from? What is the definition of professionalism? Where does elitism come from? Where are all these different beliefs? Even the way that we look at intellect and how we score ourselves. All these things have roots, they have backgrounds. Even the economic decisions and how we’ve gotten to the point of having this free market and why again those decisions were being made.

I was able to tie all of that to racist ideas, systemic racism, white supremacy. The ideal in our country is that whiteness should always be the standard, should always be what rules the country, should always be what leads the country, should always be what’s in charge. And to be successful, you have to assimilate to that. And that comes from, again, decisions that were being made based on ensuring that there was a racial hierarchy. Creating these standards in education, these standards in professionalism, these standards in our careers to ensure that that hierarchy always maintains. If you happen to be a person of color and you happen to kind of ascend higher than what, you know, the status quo says that you’re supposed to be as a person of color, well, you had to assimilate quite a bit and you had to make sure that you essentially connect yourself or tie yourself to whiteness in order to get there. And then if you happen to be a white person, there still is the fact of the matter is the standards of whiteness are also very inhuman. They go against our natural rhythms. We’ve been conditioned to believe that going against our human rhythms, being very industrial, being very work on the clock 24/7, all those things kind of tying back to again the plantation and then the industrial revolutions, all those things [tie] to where we are now. We’re conditioned to think that that’s like normal and it’s not. Even the way that we have constructed a society to ensure that black indigenous and people of color are at the bottom, it still affects everybody because now everyone is tied to this hustle mentality, this work around the clock mentality in order to make something of yourself, in order to prove yourself worthy, in order to prove yourself to be really more white, so to speak. So that America and the western world approves of you. I could go on and on and on, which, which is why I wrote the book.

Allen

What advice would you give to the young girl, the young person who’s trying to find their self-worth in this culture that’s telling them that they’re not as valuable?

Caroline

To understand that the standards that you are being told you [must] measure up to were constructed for a reason and they were constructed not because of who you are but of maintaining that hierarchy of whiteness. So, to understand that it’s really not you. Like if you think you’re constantly swimming upstream and you’re working against a current and you just can’t figure out quite what is wrong with [you], why am I always exhausted? Why am I always trying to measure up to something? Why am I always looking in the mirror and saying something is wrong with me? It is because you’re being fed these messages left and right from every corner of society to try to tell you, “Hey, you’re not worthy,” so you can spend more money, so you can keep trying harder, so you can keep assimilating, so that white supremacy can continue to be maintained. And it’s not you. It’s them. And of course, you have to still live in this world. I wish we could just take a remote and just kind of turn it off. But unfortunately, that doesn’t work that way. And I think just knowing where it comes from and knowing that you can say no to believing those things and choosing a different route in how you approach life, I think is extremely freeing. I think the knowing the roots of it [is freeing], even if you still have to play the game a little bit. Because everyone’s gonna have to play the game a little bit, especially in the workplace. I’m not saying just, go tomorrow and start just doing things differently because you might lose your job. But I’m saying at least you know the roots of something, and you can say, “Okay. I know that it’s not me. I know that society is set up like this and I don’t have to measure my worth against this.”

Allen

What message would you give for the church about how to confront white supremacy?

Caroline

Stop being afraid to talk about it, stop being afraid to have the meetings about it and looking at how you are perpetuating white supremacy in your congregations. This is not something to be afraid of. This is not something that is against Jesus. This is something that Jesus, I believe, would be for. He would be for dismantling any system that oppresses anybody else. This is the work of Jesus. And again, it doesn’t have to be simply marching in the streets when another black person is killed or there’s another racist injustice that we see. That’s important, but it is perpetuated in our boardrooms. It’s perpetuated within leadership, and it’s perpetuated with misogyny. It’s perpetuated when you refuse to play any other worship songs in your church besides a certain group that doesn’t have any people of color in it. Let’s be real. And then you dismiss somebody that wants something else because that’s not the only way to worship. There are simple ways that white’s supremacy is perpetuated, and they all need to be talked about and confronted so that every single human being that walks through your church doors feels like they are home and welcomed there and don’t have to be on edge because they’re a person of color. But again, not even just that, for everybody because my book is We’ll All Be Free, and I make it very clear that my book is written for everybody. White supremacy harms us all. It causes all of us to deal with feeling unworthy in some type of way. And so, looking at how you’re perpetuating it is the first step to dismantling it and it’s not a conversation to be scared of. It’s not work to be scared of. It’s work that is freeing.