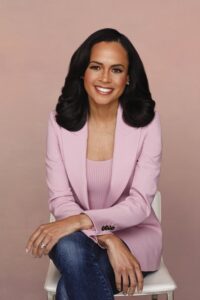

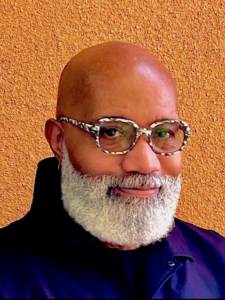

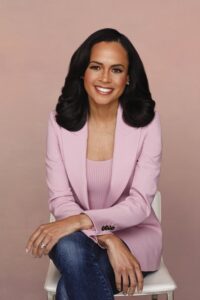

UrbanFaith contributor Maina Mwaura sat down with Linsey Davis her co-author Michael Tyler to talk about her newest children’s book The Smallest Spot of a Dot, which explores our common humanity. Excerpts of the interview are below edited for clarity and length, the full audio interview is above.

Maina:

How do you write these books, Linsey? Like you’re on the news every day. You have a big life going on. How do you do this?

Linsey:

Well, the very easy answer is Michael Tyler. He’s the brain trustee. We started working together on the last book, “The Small Spot of a Dot,” and that was something that had really been on my heart for a long time that I wanted to do a story about the Human Genome Project, but I couldn’t figure out how to conceptualize it in a way that would be palatable for the youngest crowd. And the idea that our DNA is 99.9% alike. So I just had a brainstorming session with Michael, and he immediately came up with the idea of spots or dots. And so every since that, I was like, “All right, Michael, you roll with me. We’re gonna do the next book together as well. And he has been my partner ever since. But you know what? The thing to me is that the kids’ books for me have always been the fun part of what I do. I’ve always considered myself to be a storyteller. It’s just that normally I’m talking about murder and mayhem and missing in chaos. And so I didn’t really always want my son to watch me doing the news, but he wanted to kind of see what mom is doing. But this to me was a way to share the good news. And with my first book, “The World is Wake,” which was really an homage, just a love letter to God, just about His majesty and His creations, including us. I always feel like you make time for the things you’re passionate about. And so as far as like, how do I have the time? I, one, it’s something, it’s a nice positive outlet. It’s something that I want to do. But also I think that we make time for the things that we want to do.

Maina:

Why do you think kids resonate with your book?

Linsey

Well, I’m glad to hear that that is the case. One thing I would say early on, because my son was really my muse, I would always use him as kind of the sample audience. I would look at and study what he found interesting, intriguing in books, what really grabbed his attention, the books that he wanted to keep reading again and again. And I also kind of went into this– I always feel like whatever you do, you study the greats who did it before you. And so for me, everybody would have a different opinion about who the greats are. But for me, it was Dr. Susan, Shell Silverstein. Those were the book authors who I really loved as a child. I looked at what was really effective, what really grabbed my attention. And one of the things I thought was they all had great messaging. There was meaning. They had great rhymes, but there was [meaning]. It wasn’t just about popcorn and bubble gum for the sake of it. There were things that you could really take away. And that’s what I’m hoping [to share]. It’s kind of like candy-coated medicine. Something that’s good for you but tastes good too. It goes down smooth. And I think that’s what at least I’m aspiring for. And I hope that it is resonating with kids.

Maina

So you come up with these ideas. Do you call Michael up immediately and go, hey, I got another idea? How does that work?

Linsey

Maybe we had two or three phone calls. Michael, you could help me remember first small spot of a dot when we were coming up with that original idea. But I want to say it was within that first phone call that you came up with the dots. You correct me if I’m wrong. Do you remember how that happened?

Michael

That is correct. Because I remember you calling me up after you had done a reading to a classroom of children. And I think it was. And you discussed the human genome project with a classroom of children. And you were fascinated that they were about it. And you called me up and said, there’s something here. We got to figure out how to get them to understand that. And for me, the lessons that I got in the life that lasted the longest all came by way of metaphor. My mother was a metaphor magician. And so I always thought if you give somebody a physical model to keep in their mind, they will always be able to associate the lesson with it. And then genes and double helixes and things like that are far too complex for children to comprehend. Far too complex for many adults. For me to comprehend. And so I figured particularly when Linsey and I wanted to focus on this one salient truth that came out of human genome project. And that is that 99.9% of all of our genes are alike, are identical. That only 1/10 of 1% is different than it counts for our individual looks and individual distinction. And I am thinking, how do we show them how much that 99.9 is and how much that 0.1 is? And I could do that just by getting them to understand something that’s already in their universal frame of reference. And that’s bots and dots.

Maina

I’m talking to people all across here who are asking me, are we going to make it through this? And when I see you on in the morning times, sometimes when you’re filling in, I always go, how does she do it? There’s so much bad news. So here’s a simple question. Are we going to make it through this season? I mean, are we going to come out OK, remembering the 99% here?

Linsey

Oh, yeah. I mean, to me, there’s no benefit in being a pessimist. Right? It goes back to one of my favorite quotes to Henry Ford, whether you think you can or you can’t do something, you’re right. And so, if we set out thinking, oh, boy, this is the end, then that is going to just be the beginning of the end for you personally. Right? And so I’ve always been a glass half full kind of a girl. I feel like whether it was Vietnam, whether it was the series in the ’60s, where you had JFK, MLK, RFK assassinated, I’ll bring up this quick point. I was fortunate enough to be able to do an event with Carol Simpson at the beginning of the year. And I was telling– we were talking to a class of journalists that teach at Franklin College in India. And I was saying to her– and really, they were asking questions, but I had a question for her. And that was about are things as bad now as they were then? And she felt like even though, yes, the world is on fire right now, it was so much worse in the ’60s. That was her perspective. And so the people then in the ’60s, maybe they had that same mindset of, boy, how are we going to make it? Is this the end? But they’re just like everything in life. It’s cyclical. They’re upturns and they’re downturns. The leaves fall off. They dry up. But then in spring comes the warm weather and the sunshine. And they’re back again and new revitalized. And I just feel like that’s my outlook on life. So even when things seem like, boy, just can’t get any worse and somehow it still does, I think that’s where my faith comes in. I mean, I just have to believe that as Jeremiah 29:11 says, God has a plan. And it’s for good. It’s for hope. And I just kind of live by that. And I think to not have faith is when we would become so down and out and really feeling like nothing good can come of this. I just choose to be optimistic and choose hope.

Maina

All right, Michael, I’ve got to ask this question, man. Where do you come up with these things? You take them. And it seems like you take them to another level, man. I appreciate you saying that. Do it, man. I really appreciate you saying that. I think part of it, a large part of it for me, is intrinsic. I think that everyone has a certain intrinsic trait, quality, ability that is their genius. For some people, we see them flying through there and dunking basketballs. For some people, we hear virtuosity on a horn when I listen to John Coltrane. There’s a genius there. And so for me, part of it was I had this ability, that no matter what I looked at, I had to break it down to its least common denominator. But through the years, my brain was always trained to constantly breaking things down, analyzing things. And then that gave me the ability to do reverse order on it. How do I construct it? And as quickly as I could break it down, I was able to bring it back together again and have a different understanding of it. And my fascination with words was what really drove me to be able to do this with respect to writing. Because as long as I can remember, five years old, I was always fascinated with how language came to be. Why do we even have words?

Maina

So one of my questions is, where do you get these words from? That I ended up writing? Yeah. Because the poor children, which the books are hard, Michael, they’re not easy, right? Where does that come from?

Maina

It’s really– you hit it on the head. It’s really not easy. The hardest part is the rightful for me, our children, because you have the fewest amount of words that you have to work with. And I think what enabled me is, early on in life, when other people were– for the second, third, fourth, grade, fifth, grade, sixth grade reading books, I was reading dictionaries. Because I looked at dictionaries as a way to people look at crayons. And to me, crayons allow you to draw a beautiful picture. And to me, words allow you to speak a beautiful picture. And I always wanted to be able to create the best image possible about what was in my head by using my mouth. And that meant that I had to paint with words. I had to draw with words. I couldn’t do it with tempered paints. I couldn’t do it with finger paints. I couldn’t do it with crayons. And so instead of having that eight crayon box, I was always trying to get that 148 crayon box. And that’s what’s in my head. So it started for you early. It’s what you’ve got here.

Maina

One thing I’d like to draw before we get off is– ask Lindsay, are we going to make it through?

Michael

Yeah. We’re going to make it through this season. I do wonder sometimes. She was optimistic about it. She was optimistic. And she used the word hope. And I want to give a definition for that word. Because oftentimes what I’ve learned in life is people use words and they won’t fully understand what we’re saying. That’s why we have so much communication, confusion. If you were asked a 50-year-old and a 5-year-old to define the word hope, both of them would struggle with it. If you asked them to define a word trust or truth, they would both struggle with it. And so one of my exercises in life growing up was always a write-down my own definition for a word. And the way I describe hope– and I think it varies on to what Linsey’s optimism is– to me, hope is an emotional alignment to possibility. Where you see no possibility, you are hopeless. And hopelessness to me is the most dangerous thing to the human mind. That’s what causes us to completely give up on everything. And so as long as you can align yourself to the possibility of something being better or something being more or something being recovered or something being redeemed, as long as you can align yourself to that possibility, even if it’s a 1% chance, a 1% chance is a 100% greater than no chance at all. And so I always try to align myself to the possibility of what humanity can excel to, because we’ve nowhere near gotten to that level. And there’s a big margin for us to go ahead and move towards.

Maina

Maina Maina

Maina