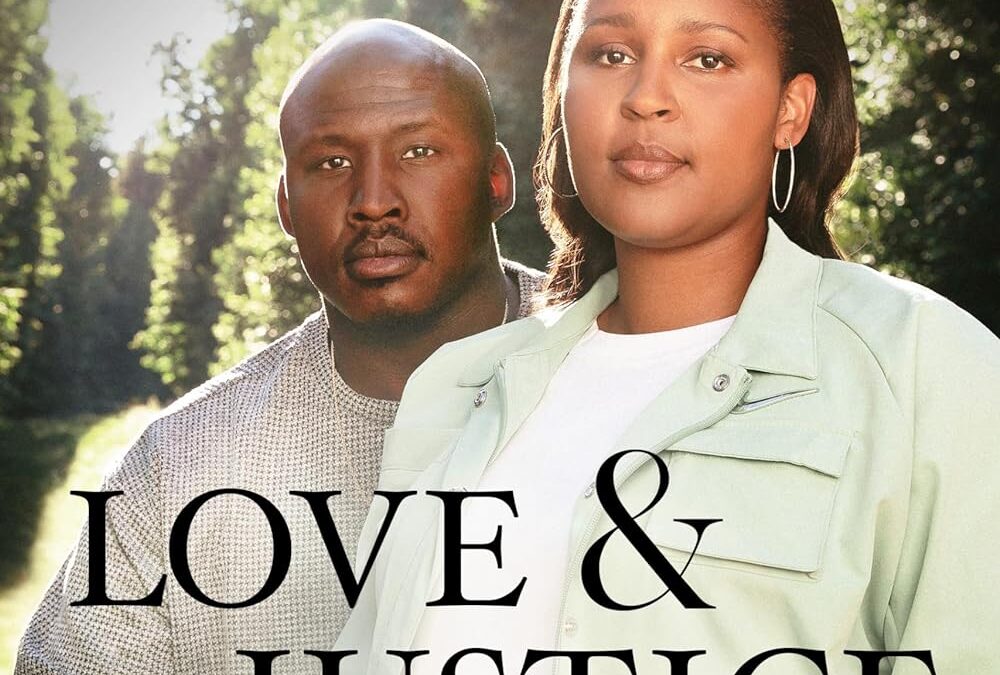

Love, Basketball, & Justice: An Interview with Maya Moore Irons & Jonathan Irons

Maya Moore was a WNBA Champion, MVP, and superstar when she left the game in her prime to pursue more justice in the US criminal justice system. The incarcerated man she advocated for, Jonathan Irons, had been advocating for prison reform from the inside. Now the two are married and sharing their story through their book Love & Justice. UrbanFaith sat down with Maya and Jonathan to talk about their incredible story following Jesus to sacrifice and live out their faith by seeking justice for the least of these. Excerpts from the interview below have been edited for length and clarity.

Allen

We are here with Jonathan Irons and Maya Moore Irons to talk about their book Love and Justice, the story of their incredible journeys; Jonathan in advocating for justice and Maya in joining in that justice fight after being a WNBA superstar. Can you talk about just that how the context and the environments that you are you all were in, allowed you to see that injustice in different ways?

Jonathan

I mean, it’s not hard. Like kids that are going on struggling and poverty and in situations that are just unfair and disadvantaged. I volunteered with kids down at the school called Peace Prep. And like they are aware, like they’re very intelligent. They are aware that they’re not getting the same type of resources and as other kids in other schools. They are aware that their city is riddled with addicts and there’s criminal activity that’s going on. They think police don’t like them and don’t care about them. And I won’t say that they’re making it up. Like I had so many different examples of things that just showed me that I wouldn’t be treated like everybody else [growing up]. And it just felt like people were being dismissive. Like my teacher didn’t like that I had so much energy. I was always up and down up and down up and down. Maya had a teacher that basically allowed her to stand around and use her energy and she turned into sports and encouraged her like, burn your energy off. Be a kid. Like for me, I didn’t have that experience. And I was aware of that. I was aware that I was treated different than other kids. I went I went to a friend’s house and they had a toilet. I didn’t have one. I’m like, man, what is that? They were like “oh that’s a toilet. That’s where we use the bathroom.” I’m used to a five gallon bucket and bathing in a tin tub. And then fast forward into prison. Like, I’m seeing like the racial inequality. I’m like, how is it that we’re the minority here [in America], but there are more black people that are in prison than there are any other race. I don’t understand this. What’s going on? And then I started to dig into it. I started to look at statistics. I started to read case law and treaties. I started to watch the news. I started asking questions. I started to let my curiosity just run wild. And I got to really see like all the injustices that are happening, happening around me. It got so bad that I overcame my own fear and I started to advocate for other people. I advocated for ice in prison because they stopped giving it to us for a long time. Filed complaints about that and basically talked to the warden face to face and like explained like, “hey, man, this is a basic human right in here that the Supreme Court has already said that we need yet we are not getting that.” And there is a list of things like you don’t have to worry about getting all those other things that were missing. Just give us this. Like just fighting for basic things. It’s like, if you if you have eyes to see, you cannot miss it. That’s why I kind of share some of the some of the things that were happening in prison to me.

Allen

And what about you Maya?

Maya

I think when we, you know, we’re born into the generation that we’re born into. And Ava DuVernay had a quote, I think she was quoting someone else about our mindset…about how we do this together. And the illustration was you inherit this house. We’re all living in this house. And we look at the house and there’s mold over here. There’s some foundations that are just rotting away. There’s broken windows over here and we say, we didn’t break that window. I’m not responsible for the mold over there. But this is the house that we’ve been given. And so it’s our responsibility to fix it as much as we can as best as we can. We have to look at people as people first and foremost. That’s the fundamental skill. Like in basketball, first thing you learn to do other than dribble is shoot. The fundamental skill is you have to be able to see people. We need other people who’ve gone before to help us know. The house is broken like what do we do? [We go to] that mom, grandma, grandpa, like somebody ahead of us. Help me know how to respond to this and say don’t panic baby I know this looks bad, but we can fix this. I had people to show me this is something we can do to help this system correct. And then also just being in relationship, that’s the majority of the work is not being afraid to be in a relationship with the people who have been stepped on. I had a measure of privilege. And I tried to use that to say hey, I’m no better than you. We’re both humans, you deserve to be treated like a human. I’m just saying everybody have basic humanity. Then your work ethic, or your gifts can kind of, you know take you where it goes but basic humanity cannot be a negotiable. So that’s kind of where I came in of like, I didn’t know this was happening. We need to do something because we can do something with this house that we inherited.

Allen

Can you talk about what you how your faith has motivated and played into [your work]?

Jonathan

Yeah, as you look into the Bible, you won’t find Superman in the Bible. You won’t find Batman. You won’t find people that were flawless outside of Jesus. Like everybody [had flaws]. Moses was a murderer. You could just pick anybody a character in the Bible any person in the Bible and see something. And what that does is it lets you know you’re not alone in your flaws and your weaknesses. And what that does, they call us to remember when we see other people that are struggling that are going through things. It calls us to look at them like, “hey, I have my weaknesses. We all need to have compassion on each other. We all need to help each other.” It calls us to remember those people that are less fortunate than we are.. We are supposed to want them to have the same things that we would want. We have to remember the vulnerable. Everybody’s got something going on, whether they want to admit it or not, whether it’s in the forefront or not, we all wrestle with things. And we are called to just lean into each other and be a part of community and show up for each other. And be present and speak out against injustice and things that are happening in this world. And me reading through the Bible and seeing that playing that out. Like, that is that is that to me that’s God talking to me through this word, and through other people, through my environment. God is asking you to remember those people and care for those people where you can that are disadvantaged.

Allen

Yeah, Matthew 25 right, if you did for the least of these you did it to me. Maya, can you talk about how your faith plays into this work? Because it’s a huge step going from where you were to where you are now and focused on caring for the least of these and seeking justice.

Jonathan

I was one of the least of these.

Maya

Man, understanding God’s story, right? God has given us a story. And he says there’s a competing story. There’s the story of the world, of the flesh, of devil is like what does that mean? And it’s a way of seeing that is contrary to the kingdom of God. Every day, we have a choice to make. Are we going to believe God’s story, which is the real story or are we going to believe this world story, this empire story? I think we just unfortunately see some of these systems that have been set up in our house right… in our culture. That are so empire and just crush people and dehumanize and devalue and use and manipulate and coerce all based off of [the idea that] I want to preserve myself.

I’m so fortunate to have been able to feel like I’ve been walking with the Lord since around middle school where my faith became my own, before my name became a name. I had that basketball experience with an awareness [that] my identity is “I’m God’s daughter,” and my purpose is not building my name [or] becoming the best, or making the most money. That wasn’t what got me up out of bed. And so when the when the time came where God was like really making it clear to my heart the shift that I needed to make out of that sports entertainment rhythm into a different rhythm that was unknown. [What was it] going to look like when I stepped away from the game in 2019? But I knew it was leading me towards doing more in this kingdom story that I was learning more about, which required me to give some stuff up; some of my comforts, my status or whatever you want to call it in order to be the hands and feet of Jesus and show up and do the hard things and get educated humble myself learn from people. When I was able to speak and use my platform, I could be helpful and accurate in trying to encourage and equip people. It’s about seeing God’s kingdom as clearly and as rightly as I can and then being able to live my life in a way that makes that kingdom a reality as much as I can every day. Which again is going to probably mean some sacrifice right, love costs. Jesus did sacrifice a lot for love, restoration, and redemption. But it was for the joy that was set before Him. Looking ahead to that future joy. We might not see the full benefit of what our lives are going to do but we’re tasting it now in bits. Until that fullness comes into play. But it is the center of all that we do.

Allen

Jonathan your story is unfortunately not unique enough that there are so many people who are subject to this criminal justice system that the statistics are pointing to that, but that you offer hope that there is something in the midst of it to be gained and that there are is a fight to be fought. Maya you gave up a lot. But showed there’s more to life than WNBA of success and living out our faith can mean a lot for us. So I just thank you both so much. Any last words of wisdom for young folks were out there?

Jonathan

I want to say you can’t make this type of story up. [The one I lived.] You can’t do that. And I’ll say this, it can be your darkest moments. Don’t forget that God loves you. And God got your back. All you got to do is seek a relationship with Him. I promise you. You won’t regret it.

Allen

Maya any parting words?

Maya

I would just say when you get discouraged because it can be [discouraging], it’s just it’s part of life. If you look into the dark it’s discouraging, but don’t stay there. There is something. There are people. There are things in motion that are happening that you can plug into. I’d say get plugged in to something because we can’t just look at the dark things by ourselves in our inner room. If we’re going to look at hard stuff you’ve to link arms and be like, we’re going to look at this together and we’re going to do something together. So, my encouragement is always get plugged in to something already happening and stuff will happen out of that. Keep encouraged and keep moving forward. The black church has modeled resilient ways for centuries. It’s not a new thing. There’s a legacy there. Learn and plug into those elders. There are people who have [wisdom], there’s jewels that are still alive that we can have conversations with and glean from. Let us continue to lift up our people who have gone before and make sure they’re appreciated and that we’re receiving what they can pour out. Because those are team members that need to be honored and still have something to offer us. Keep learning.

Nika

Nika

Allen

Allen