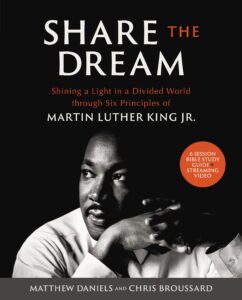

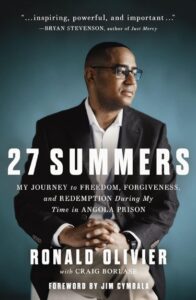

27 Summers: Ronald Olivier x UrbanFaith

UrbanFaith Editor Allen Reynolds sat down with prison chaplain and author Ronald Olivier to talk about his story of going from a life of poverty and violence to facing a life sentence in prison to being saved and freed by the power of Jesus Christ in his amazing book 27 Summers. The full interview is above, below are excerpts edited for clarity and length.

Allen

I am excited today to have with me an author, a chaplain, a man of God who has an incredible story and an incredible journey to share. And that is Mr. Ronald Olivier sharing to tell about [his] book: 27 Summers. One of the things people don’t realize is how long the justice system can take. Can you talk a little bit about the trouble of getting used to living a life that is violent or that is trouble? And really, I’m trying to get to how the idea of living a sinful lifestyle can feel so normal that we don’t realize that sooner or later it’s gonna catch up [to us].

Ronnie

Yeah, I think one of the tricks is what the enemy uses is that belief that you will never get caught. Yeah, [they] got caught, but not you. You too slick, you too sharp. He just lets us see all that we can accumulate, all this stuff, the money, the fame that comes with it. But never let us see the end of it. And most of my friends never made it out of their teens. Murder was all around me and I really thought that was my fate. I felt that’s how I supposed to go. I thought this was a way of life. You do what you do, live as long as you can live and die. And I always thought I would die before I was 21. I never thought I’d make it out my teens.

You just become accustomed to it. It’s like I heard a story about boiling a frog. You never just put them in hot water. You put them in temperate water and let the temperature increase and he’ll stay there and boil. But if you just drop them in hot water they get out.

So that’s how sin is. You know, it progresses, and you can’t figure out how to get out. I really felt like that was my fate and I couldn’t get out. Now I can look back and see all the escape routes that God was trying to get me out on. But the enemy had been blinding my mind so much to make me think that there was no way out and that’s one of the greatest lies of the enemy. Man, you’re stuck there. You never get out. This is the way life is supposed to be. No, that’s a lie.

Allen

Yeah, and I think that’s so seductive. I want to take you to that moment which I think was God moment where you realized that you weren’t going to get the death penalty but instead, were going to get life in prison. Can you talk about just what it was like literally to be placed between death and life and to find out you got life?

Ronnie

Yes, so I’m on trial for first degree murder facing the death penalty. And up until that point, everything was fun and games to me. It wasn’t real. I thought I was getting out. I didn’t feel the weight of it until I placed in the holding tank about 12 AM, 1 AM in the morning while the jury was deliberating. I can still hear the iron door slam and the key turn. And I could still hear the guards footsteps fading off until I couldn’t hear him no more. And I’m there alone in a box. And man, the weight of that was going on came crushing down on me. I was like, whoa, there’s 12 people that don’t know anything about me that are making the decision on whether I live or die. I was like, wow. And at that moment I was like, man, I don’t wanna die. I believe God used my mother’s voice. I heard her saying this so clearly to me. It was so loud in my spirit to where she said, son, if you ever in trouble that I can’t get you out, you should call on Jesus. And at that moment, I got on my knees. I’m crying and I called out to Jesus, and I had a very simple prayer. I made a deal with God. A lot of people say you don’t make deals with God. I made a deal with Him. And I said, Lord, if you don’t let them kill me, I promise you, I’ll serve you the rest of my life. And for the first time in my life, I had experienced and felt the peace of God. There was a peace that came. I didn’t know what it was then, but I just had this inward resolve that I was gonna be okay. It was this calmness that came over me. And so the jury came back with a guilty verdict of the lesser offense. That carried a mandatory life sentence without benefits of parole or probation. In layman’s terms, you die in prison. You never get out. But I like to put it like this in that holding tank, I received two life sentences. You know, the state was giving me a life sentence with no benefits. But God was giving me a life sentence with so many benefits that he encouraged me in His word to not forget them. So there it is, man. I get this life sentence and I’m headed to penitentiary. Not just jail, but penitentiary, which is a big difference.

Allen

A lot of times we think that, you know, we give our lives to Christ and then they just get better all of a sudden. I love that your story is not a story of an instant change. Why is that important?

Ronnie

I think that’s very important because I know it helped me to be patient with other young believers because you could be you could be very judgmental if you’re not careful and say, oh, they’re not born again. They’re not. But, when you think about it, just like in the natural, when a baby comes out of the womb, the baby looks like what it came out of. And so that baby, you know, that baby don’t come out looking like the little [girl or boy they will be when they’re big.] The baby looks like a little prune with all type of afterbirth on. They have to go through a process to be clean, to be fed, to be to be changed. And the baby is totally dependent on someone else. And so that’s what the discipleship comes in, you know, and even though I knew I was born again, I look like what I came out. I still was doing some of the same things. But I continued to go to church. A lot of people [put] pressure on guys, you’re going to church, you’re still doing all that. As if you’re supposed to be perfect when you go to church. But and not realizing that the church is, it’s man, it’s a spiritual hospital. People go there because they’re sick. We’re all getting some type of treatment. If you break your arm, you don’t wait till it get well, then go to the hospital. That’s absurd, you know, I’m going to get some treatment because I’m broken because I have all these issues because, you know, I’m messed up and I’m wrapped up in sin. That’s why I’m going to church. And man, we need to have people with that understanding when guys get to church to help them to disciple, to love on them, to get them where they need to be. And that’s what guys did for me, man. They discipled me. They didn’t judge me. They kept pushing me in the right direction, kept praying for me, you know, and kept being there for me. And man, that’s so important and helping young believers because they look like they’re not nothing really changed. But something did happen in their hearts, and it takes a process. And that was going on the inside coming on outside where you can see it and enjoy.

Allen

What advice would you give to young adults now who may be feeling hopeless or may feel like there’s not any way out of their situations? Because I think your story really speaks to that.

Ronnie

One thing I would say is to have hope. Man, you got you embrace the hope of glory, which is Jesus Christ. There is absolutely no hope without him. And so I would encourage you to develop that relationship. I’m not talking about religion. I’m not talking about just going to church. I’m talking about having a real personal relationship. Spending time with him, you develop your ear to hear his voice, to distinguish his voice from any other voice and allow him to lead and direct you. I was in prison. God said, look, don’t go that way. Go over here. And something would happen over there. You know, I get drugged up or killed and all this other thing. And he was he was leading and protecting me in the midst of chaos. He would do the same thing for you. But he’s not a respecter of person, but he is a respecter of faith. He just looking for someone to believe Him at His word. And I promise you God can do exceedingly, abundantly, above all you ask or think, but it’s going to be according to the power that’s working in you. You got to let him work in you. And so I just encourage you with that.