Republished from Religion News Service

(RNS) — At St. Ann’s Episcopal Church in the Chicago suburb of Woodstock, Illinois, the once weekly Christian education program is now monthly, and known as “Second Sunday Sunday School.”

At Crossroads Community Cathedral, an Assemblies of God church in East Hartford, Connecticut, “children’s church” continues to thrive each weekend, and “The Little Drummer Dude” production was presented in early December, but Christian education for young people is described as “one of our greatest weaknesses.”

At Mattie Richland Baptist Church in Pineview, Georgia, the adults have been back in Sunday school and the kids led a Black history presentation, but the bus that picks up children for their education program will remain idle until January.

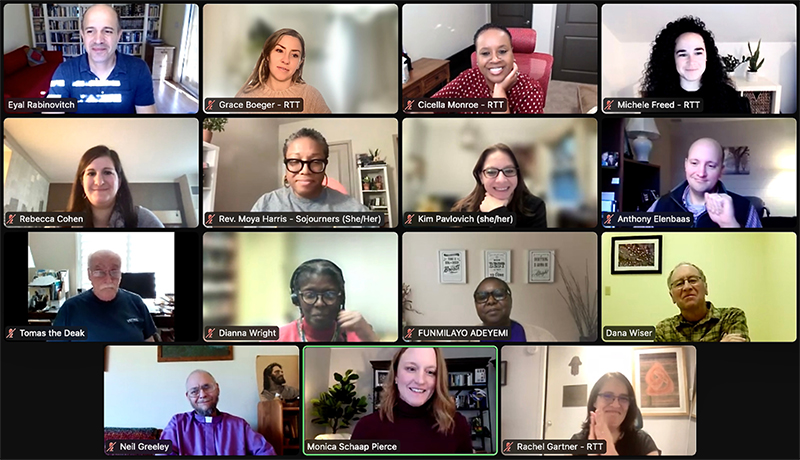

Sunday school, adult forums and other Christian formation classes, already threatened by declines in worship attendance, have been further challenged since COVID-19 shuttered churches and sent their services online. A study by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research said more than half were disrupted in some way. Other research shows religious education for adults has bounced back more than for younger church members.

Scott Thumma speaks during the annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion on Nov. 12, 2022, in Baltimore. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“For some, it continued without any real major disruptions, and for others, it basically collapsed,” said Scott Thumma, the institute’s director, summing up its 2022 pandemic-related research during an October event at Yale Divinity School. “And the easiest way to make it collapse was to keep religious education for children and youth online. If you kept it online, you probably don’t have a religious education program now.”

The Rev. Scott Zaucha, pastor of St. Ann’s in Woodstock, a mostly white congregation with about 50 attending on Sundays, said its Sunday school had ceased to exist before the pandemic because of its aging congregation. He wondered how to begin it again and learned that online Christian education was not the answer because it seemed like “another thing to try to keep up with” when regular schooling was online.

RELATED: Half of churches say Sunday school, other education programs disrupted by pandemic

Zaucha found that meeting one Sunday a month in person was the best route, realizing that even if families choose St. Ann’s as their congregational home, they may not be weekly attenders.

“When you have only a few families with kids at your church, and you have two kids on this Sunday and six kids on that Sunday,” he said, “they’re all sort of spread out. But if you say, ‘Hey, families, we’re going to have Sunday school once a month.’ Then it lets them know when is the best Sunday for them to come if they’re only going to choose one.”

Crafts made by children in Sunday school classes decorate St. Ann’s Episcopal Church in Woodstock, Illinois. Photo courtesy of St. Ann’s

In Orthodox churches, research shows that the parishes that never ceased holding in-person religious education classes for their children and teenagers fared better than those that halted the Sunday school lessons, with some even increasing the number of attendees. The combination of attending worship as well as Sunday school and seeing other youth on a regular basis became crucial for their participation.

“For them, it has become even more valuable through the pandemic for those parishes, which kept young people together,” said Alexei Krindatch, national coordinator of the National Census of Orthodox Christian Churches, in an interview conducted at the Religious Research Association conference in November. “It was an excuse to get together.”

At Crossroads, a multicultural congregation with about 1,500 gathering each weekend, online campus pastor Luke Monahan has tried numerous options to keep adults and kids engaged since the start of the pandemic. In 2020 there were daily adult devotional videos and two a week for kids. Online options appealed more to the adults than to the kids — his own youngster, at age 6, “shut the little laptop and ran away,” he said. An online kids’ church video he had developed gained little traction.

“One month, I didn’t put it out and didn’t notify anyone on purpose,” said Monahan, who also directs IT and education at the Connecticut church. “Nobody said, ‘Where did that video go?’”

Thumma said in his presentation at Yale that adults have had a much more positive reaction to religious education that is not in person. “Adults seem to love religious education online,” he said. “And we’re hearing stories about all kinds of Bible studies, all kinds of prayer meetings, all kinds of education events that are happening online for adults, but not for children and youth.”

Publishing companies are seeking to respond.

Urban Ministries Inc. has found that adults, even those who aren’t tech-savvy, are interested in its digital platform, Precepts Digital, which launched this year. The video-enhanced Bible study is meant for individuals or small groups.

An individual uses the Precepts Digital Bible study program. Photo courtesy of Urban Ministries Inc.

“We have been encouraged by the oldest members of our audience embracing digital,” said UMI CEO Jeffrey Wright, whose Christian education publishing company primarily serves African American congregations. “You expect pushback from nondigital natives. And in one focus group, a person commented, ‘Well, you know, it’s harder but it’s worth it.’”

After the pandemic caused a significant drop — Wright estimates a 60% to 80% decrease — in requests for materials for children and youth in the African American community, the company is working on a children’s version of its digital Bible lessons.

“We have a crisis of catechism going on in America right now,” Wright said, expressing concern for the religious upbringing of the youngest generation.

“If you think about it, a 4- or 5-year-old kid, say, born in 2017 or 2018, has never been in an Easter program or a Christmas program and given that little speech you gave when you were a little kid up in the front of the church. Hasn’t happened. Children aren’t being served.”

Children color an Illustrated Ministry poster during Advent. Photo courtesy of Illustrated Ministry

Illustrated Ministry, a 7-year-old publishing company that aimed at progressive Christian congregations, also has sought to provide materials to churches as they shifted from in-person to online and, sometimes, back and forth again, depending on the stage of the pandemic.

Adam Walker Cleaveland, who founded the company in Racine, Wisconsin, said he is seeing a greater demand for resources that provide stand-alone lessons for those who may not be attending Sunday school week after week.

Adam Walker Cleaveland. Photo by Karen Walker

“Since COVID, we have seen increasing need for curriculum and resources that are extremely flexible, extremely adaptable,” he said.

Though many of Illustrated Ministry’s products, including children’s bulletins, children’s ministry curricula and pages to color, are designed for children, they can also be used in intergenerational activities around a table at home.

Walker Cleaveland said his organization is also keeping in mind the volunteer teachers — also in shorter supply since the start of the pandemic — who are preparing for Bible lessons, making sure the work is not too time-consuming.

“In terms of our materials, we try to make it so that there isn’t that in-depth prep required, there’s not a huge supply list,” he said. “So you don’t have to make a trip to Michael’s every week before Sunday school.”

Pastor Florine Newberry, who leads Mattie Richland Baptist, said its membership rolls have grown from 50 to 96 as the congregation shifted from predominantly Black to a more diverse group after welcoming people who stopped to listen to her outdoor sermons during the pandemic.

After preaching at her church’s front door to people who remained seated socially distant near their cars, the congregation is back inside and adult Sunday school started earlier this year. But formal Christian education for teens and children has been limited due to the pandemic and concerns about respiratory syncytial virus, commonly called RSV.

Youth give presentations on Black history at Mattie Richland Baptist Church in Pineview, Georgia. Photo by Ja’Qwan Davenport

Instead, Newberry has picked up the phone and suggested particular Scriptures to encourage them when they told her of bullying that’s occurred at school.

But Newberry is looking forward to Jan. 1, when she expects to use her church’s bus to pick up children for Sunday school after deciding it is safe to transport them again.

“If you can get ’em while they’re at that age, you can really make a difference,” she said of the children who’ve been inquiring about when she’s going to pick them up.

“Once I get them back in Sunday school, I’ll be happy.”