by Allen Reynolds, UrbanFaith Editor | Dec 14, 2021 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Social Justice |

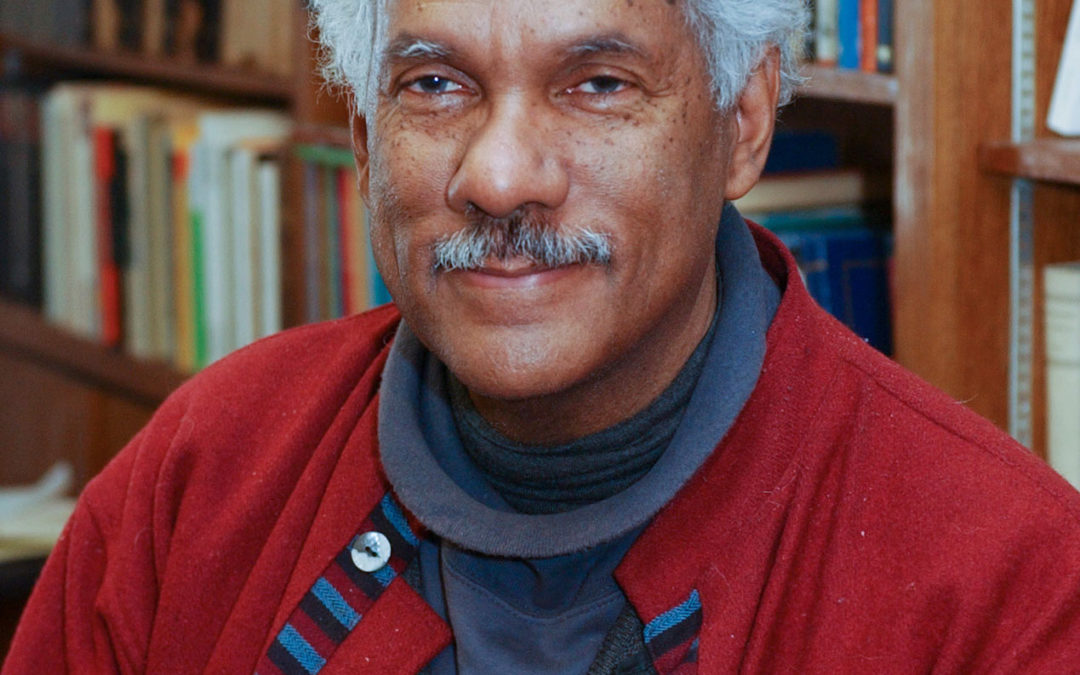

Rev. Dr. Frederick Haynes III is no stranger to speaking truth to power and empowering black communities. He has been leading Friendship West Baptist Church in Dallas, TX for decades as they empower Black people spiritually, economically, and politically.

UrbanFaith sat down with Dr. Haynes to discuss their recent #100DaysofBuyingBlack initiative which honors and extends the legacy of Black Wall Street as part of their commemoration of 100 years since the Tulsa Race Massacre and bombing of Greenwood in 1921. Friendship West encourages us to buy from black businesses starting with this 100 day campaign and continuing into the future. More information about the initiative is below.

—-

Friendship-West Baptist Church is taking things to the next level in the conclusion of its year-long commemoration of the Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Okla. by promoting 100 Days of Buying Black (100DBB). Participants are challenged to use Black-owned businesses for their service and product needs for 100 days nationwide. Led by senior pastor and social justice activist, Rev.

Dr. Frederick D. Haynes III, the goal of this challenge is to continue the legacy of Black Wall Street by circulating dollars within the Black community to strengthen its economic base. 100 Days of Buying Black will start on September 23, 2021 and will end on December 31, 2021.

As Friendship-West strives to carry the torch and reimagine a new Black Wall Street for Black communities across the nation, participants are encouraged to track and report their weekly spending with black-owned businesses. Friendship-West will measure the number of dollars spent in the black community by participants and provide weekly check-ins. Participants can visit friendshipwest.org/buyingblack100 to download the weekly spending tracker and report their amount.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Nov 4, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

(RNS) — Two and a half centuries ago, Francis Asbury arrived in the United States from Great Britain, bringing with him what would become the Methodist faith. He went on to spread it across the country, with St. George’s Church in Philadelphia as his home base.

St. George’s will mark the occasion of Asbury’s arrival with a weekend of events at the end of October. But the historic church, which remains the oldest continually used Methodist building in the United States, is also the starting point of three African American churches and one denomination after a “walkout” by Black worshippers.

Over time, recounts the Rev. Mark Salvacion, St. George’s current pastor, African Americans —some recently freed from slavery — were segregated to the sides of the church, to the back of the building and to a balcony, preventing them from receiving Communion on the church’s main floor.

Salvacion describes this and other parts of St. George’s history in the church’s “Time Traveler” program for teen confirmation students learning about their faith and in classes of middle-age adults training to become certified lay ministers.

Teenage confirmation students attend a “Time Traveler” program at Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia in 2018. Photo courtesy of HSG

“It’s not just telling happy stories about Francis Asbury itinerating to West Virginia,” said Salvacion, pastor of what is now called Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church. “It’s uncomfortable stories about race and the meaning of race in the United Methodist Church.”

The turning point for many African American worshippers, already dissatisfied with mistreatment, was a Sunday morning in the late 1700s. Lay preacher Richard Allen saw another Black church leader, Absalom Jones, forcibly pulled up while praying on his knees at St. George’s.

That led Allen and some of the other Black attendees to leave what was then known as St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church and strike out on their own — in different ways.

Portraits of Absalom Jones, from left, Harry Hosier and Richard Allen in Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church museum in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of HSG

“This raised a great excitement and inquiry among the citizens, in so much that I believe they were ashamed of their conduct,” wrote Richard Allen in his autobiography. “But my dear Lord was with us, and we were filled with fresh vigour to get a house erected to worship God in.”

In 1791, Allen, who had been a popular preacher at St George’s 5 a.m. service, started what is now Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Asbury dedicated its first building, a former blacksmith shop, in 1794.

“Here’s Asbury and he comes in and he still has this kind of relationship with Richard Allen that is more than just collegial,” the Rev. Mark Tyler, current pastor of Mother Bethel, said of the men who were the first bishops of the Methodist and AME churches, respectively.

“I mean, you go out of your way as the representative and the saint of Methodism in America and you dedicate Mother Bethel. That is a statement that you’re behind this and endorsing it.”

Bronze statue of Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, on the property of Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia on July 6, 2016. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

In 1816, after winning a court battle for its independence from the Methodist Episcopal Church, Allen started the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the nation’s first Black denomination.

Jones went on to serve as a lay leader of the African Church that began in 1792. Two years later, the congregation became affiliated with the Episcopal Church and was renamed the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. Jones was ordained a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802.

Arthur Sudler, director of the Historical Society & Archives at the 1,000-member church, said the 250th anniversary of Asbury’s U.S. arrival is significant not only for the three Philadelphia congregations that began after discord with St. George’s but also for the city and the three denominations they now represent.

“It’s an epochal moment simply because Francis Asbury’s role in helping develop Methodism in America, in part through his participation there at St. George’s, is one of those factors that gave birth to the Black Christian experience in Philadelphia,” he said. “And in America more broadly, because of the seminal role of Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, and Harry Hosier and their connections between what became these three denominations, the AME Church, the United Methodist Church and the Episcopal Church.”

Service at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in 2019. Photo by Dale Williams for D’Zighner Studios

Hosier initially stayed at St. George’s with other Black attenders who did not leave with Jones and Allen. He also was a closer colleague to Asbury than the other two men, having been a traveling companion who preached with the Methodist leader across the South. Allen, a free man, had declined the offer, avoiding a risky return to the region of the country where slavery remained legal.

Hosier helped found another Philadelphia Methodist congregation, which initially met in people’s homes and eventually became known as Mother African Zoar United Methodist Church. Asbury dedicated its building in 1796 and preached there a number of times, according to the United Methodist Church’s General Commission on Archives and History.

After it celebrated its 225th anniversary, Mother Zoar retained its name but merged with New Vision United Methodist Church in north Philadelphia, with a current average of 75 people at in-person worship services. It thus remains the oldest Black congregation in the United Methodist tradition in continuous existence.

Portrait of Francis Asbury in 1813 by John Paradise. Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery/Creative Commons

Given the steps of Allen and Jones, why did Hosier and other Black worshippers who once prayed at St. George’s remain within the Methodist Church?

“That is a million-dollar question,” said the Rev. William Brawner, the part-time pastor of Mother Zoar.

He said he assumes “those who left with Absalom, those who left with Richard were tired and figured that they could not change the system of injustice from the inside.” The founders of Zoar chose a different approach, hoping that remaining Methodist would help “change the hearts and minds of the people that were literally oppressing them.”

All these years later, Brawner said he does not judge the different decisions made by African American worshippers at St. George’s, who were unable to freely use spiritual practices that were different from those of white congregants and reflected beliefs some had brought with them from Africa.

“I think people left because of feeling uncomfortable and unaccepted in one place,” he said. “So the split could be celebrated now because of what has become of the split, but people didn’t split out of privilege. People split out of pain. They split because they were hurting.”

The emotions arising from the divisions transcended the centuries.

The Rev. Mark Tyler. Courtesy photo

Tyler, whose church has more than 700 members today, recalled the 2009 service when congregants of Mother Bethel worshipped at St. George’s for what was believed to be the first joint Sunday morning service since the 1700s. As the preacher for that day, he said the gathering was a “cathartic moment,” prompting many of his church’s members to weep.

Salvacion and the clergy of the other churches say occasional joint gatherings have continued since then, such as some of the congregations sharing Easter sunrise services and the annual Episcopal Church observance honoring Absalom Jones.

St. George’s currently has about 15-20 worshippers and a membership of about 50. It expects dozens of United Methodists and invited guests from other churches to attend the Oct. 30-31 commemoration.

Its pastor also expects exchanges and shared events will continue in the future among the congregations whose first members left his church building.

“We all view this history as being common history that we share,” said Salvacion, an Asian man who is one of St. George’s first pastors of color.

Interior of Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative Commons

Tyler said the ongoing connections between St. George’s and Mother Bethel probably weren’t envisioned by anyone two centuries ago.

“The current relationship of these two congregations is, in some ways, a sign of hope for what’s possible,” he said. “If it can happen in these two congregations maybe it’s possible for us as a country and as a world. I have to take it for what it is — just a small sign of hope, in spite of all the kind of guarded optimism that I have.”

by Ben Finley, Associated Press | Oct 15, 2021 | Black History, Headline News, Heritage |

Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, holds a one-cent coin from 1817 on Wednesday Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. The coin helped archaeologists confirm that a recently unearthed brick-and-mortar foundation belonged to one of the oldest Black churches in the United States. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (AP) — The brick foundation of one of the nation’s oldest Black churches has been unearthed at Colonial Williamsburg, a living history museum in Virginia that continues to reckon with its past storytelling about the country’s origins and the role of Black Americans.

The First Baptist Church was formed in 1776 by free and enslaved Black people. They initially met secretly in fields and under trees in defiance of laws that prevented African Americans from congregating.

By 1818, the church had its first building in the former colonial capital. The 16-foot by 20-foot (5-meter by 6-meter) structure was destroyed by a tornado in 1834.

First Baptist’s second structure, built in 1856, stood there for a century. But an expanding Colonial Williamsburg bought the property in 1956 and turned it into a parking lot.

First Baptist Pastor Reginald F. Davis, whose church now stands elsewhere in Williamsburg, said the uncovering of the church’s first home is “a rediscovery of the humanity of a people.”

“This helps to erase the historical and social amnesia that has afflicted this country for so many years,” he said.

Colonial Williamsburg on Thursday announced that it had located the foundation after analyzing layers of soil and artifacts such as a one-cent coin.

For decades, Colonial Williamsburg had ignored the stories of colonial Black Americans. But in recent years, the museum has placed a growing emphasis on African-American history, while trying to attract more Black visitors.

Reginald F. Davis, from left, pastor of First Baptist Church in Williamsburg, Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist, and Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, stand at the brick-and-mortar foundation of one the oldest Black churches in the U.S. on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. Colonial Williamsburg announced Thursday Oct. 7, that the foundation had been unearthed by archeologists. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

The museum tells the story of Virginia’s 18th century capital and includes more than 400 restored or reconstructed buildings. More than half of the 2,000 people who lived in Williamsburg in the late 18th century were Black — and many were enslaved.

Sharing stories of residents of color is a relatively new phenomenon at Colonial Williamsburg. It wasn’t until 1979 when the museum began telling Black stories, and not until 2002 that it launched its American Indian Initiative.

First Baptist has been at the center of an initiative to reintroduce African Americans to the museum. For instance, Colonial Williamsburg’s historic conservation experts repaired the church’s long-silenced bell several years ago.

Congregants and museum archeologists are now plotting a way forward together on how best to excavate the site and to tell First Baptist’s story. The relationship is starkly different from the one in the mid-20th Century.

“Imagine being a child going to this church, and riding by and seeing a parking lot … where possibly people you knew and loved are buried,” said Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist. She is also board president of the Let Freedom Ring Foundation, which is aimed at preserving the church’s history.

Colonial Williamsburg had paid for the property where the church had sat until the mid-1950s, and covered the costs of First Baptist building a new church. But the museum failed to tell its story despite its rich colonial history.

“It’s a healing process … to see it being uncovered,” Harshaw said. “And the community has really come together around this. And I’m talking Black and white.”

The excavation began last year. So far, 25 graves have been located based on the discoloration of the soil in areas where a plot was dug, according to Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology.

Gary said some congregants have already expressed an interest in analyzing bones to get a better idea of the lives of the deceased and to discover familial connections. He said some graves appear to predate the building of the second church.

It’s unclear exactly when First Baptist’s first church was built. Some researchers have said it may already have been standing when it was offered to the congregation by Jesse Cole, a white man who owned the property at the time.

First Baptist is mentioned in tax records from 1818 for an adjacent property.

Gary said the original foundation was confirmed by analyzing layers of soil and artifacts found in them. They included an one-cent coin from 1817 and copper pins that held together clothing in the early 18th century.

Colonial Williamsburg and the congregation want to eventually reconstruct the church.

“We want to make sure that we’re telling the story in a way that’s appropriate and accurate — and that they approve of the way we’re telling that history,” Gary said.

Jody Lynn Allen, a history professor at the nearby College of William & Mary, said the excavation is part of a larger reckoning on race and slavery at historic sites across the world.

“It’s not that all of a sudden, magically, these primary sources are appearing,” Allen said. “They’ve been in the archives or in people’s basements or attics. But they weren’t seen as valuable.”

Allen, who is on the board of First Baptist’s Let Freedom Ring Foundation, said physical evidence like a church foundation can help people connect more strongly to the past.

“The fact that the church still exists — that it’s still thriving — that story needs to be told,” Allen said. “People need to understand that there was a great resilience in the African American community.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 12, 2021 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Heritage |

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in 2016. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

(RNS) — A century and a half ago, nine young men and women embarked on a trip from Fisk University, establishing a tradition of singing spirituals that both funded their Nashville, Tennessee, school and introduced the musical genre to the world.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, based at the historically Black university founded by the abolitionist American Missionary Association and later tied to the United Church of Christ, started traveling 150 years ago on Oct. 6, 1871. They since have continued to sing so-called slave songs such as “Down by the Riverside” and “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and stood on stages from New York’s Carnegie Hall to Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium.

Musical director Paul Kwami has led the group since 1994 and sang with it when he was a Fisk student in the 1980s. Then and now he views the songs as not only expressions of the religious beliefs of enslaved people, but also of the original singers and the ones who continue to sing today.

“There are songs like ‘Ain’t-a That Good News,’ which is a song that talks about having a crown in heaven, having a robe in heaven,” said Kwami, a member of a nondenominational Full Gospel church in Nashville. “Well, they’ve never been to heaven, but then they’re singing about heaven — that’s an expression of faith.”

Kwami, a native of Ghana, in West Africa, talked with Religion News Service about how the ensemble began, who should sing spirituals and which of the songs are his favorites.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in Jubilee Hall at Fisk University on Oct. 29, 2020. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers won their first Grammy in 2020 for an album that celebrates almost a century and a half of music. What does that say about the endurance of the group and the music that they have sung for so long?

The album was actually produced on the (university’s) 150th anniversary. But then, of course, it is the Fisk Jubilee Singers who won the Grammy, which actually makes me realize that people still recognize who the Fisk Jubilee Singers are. And people still appreciate the music. Additionally, people realize Fisk Jubilee Singers are artists and do not limit themselves to just Negro spirituals. There’s versatility in our choice of music when we have celebrations.

How do you define spirituals, and differentiate them from other forms of African American music sung in Black churches and beyond?

The Negro spirituals are songs that were created by the slaves during their time of slavery. But when we talk about music like jazz or blues or gospel, those genres of music came long after the Negro spirituals were established. And some people even say these other forms of music were birthed out of the Negro spirituals.

When we talk about the Negro spiritual and, say, gospel music, the performance styles are completely different. Gospel music simply deals with church music with a lot of instrumental accompaniment, clapping, a lot of improvisation. But with the Negro spiritual, even though there may be some improvisation, it doesn’t involve a lot of improvisation. Traditionally, Negro spirituals don’t call for instrumental accompaniment.

When the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing, the music is a cappella. The original Fisk Jubilee Singers transformed the Negro spiritual into an art form or concert spiritual. And because of that, clapping, for example, is not recognized as part of a performance of Negro spirituals.

Spirituals are known for their layers of meaning, some of which were hidden to slave masters. Can you give an example of one that is often sung by Fisk Jubilee Singers that reflects that?

One we often sing is “Steal Away to Jesus.” (One) meaning is that we will run away to the North — because we’re stealing away to Jesus — and Jesus was referring to a place of freedom.

When George White, a music professor and Fisk’s treasurer, decided to have singers from the school perform the spirituals for white audiences as fundraisers, was his idea supported by many or was it controversial or both?

To leave Fisk with a group of students to go on a tour, singing to raise money — that was opposed. The administration at Fisk at that time did not believe he would succeed. They thought this was more of an experimental adventure because no one had ever done that. He was not sure of how audiences would receive Black young people singing so he taught them to sing Western (and European) classical music with a hope that would be more attractive to the various audiences. The Fisk Jubilee Singers were also not willing to sing the Negro spirituals because those songs were very sacred to them. But eventually, they started singing the Negro spirituals to the delight of their audiences.

The spirituals were “concertized” for performance for these fundraisers. Do you think anything was lost as the songs moved from the field where slaves had labored to concert halls where people paid to hear them sung?

I don’t think anything was lost. I read a quote by one of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers, and in this book he transcribes some of the songs they sang. I look at the melodies and they’re the same melodies we sing except the arrangements may be different.

How were the singers received at a time when slavery had just ended and African Americans were not welcome in many venues that were segregated?

Originally, they were not well received. There are accounts where people would go into the concerts, listen to the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing and not even give donations. There are accounts of Fisk Jubilee Singers going into hotels and hotel owners, realizing they were Black people, turned them away, wouldn’t give them a place to sleep or food to eat. There was a time when George White was able to purchase first-class coach (train) tickets for them but they were refused admittance into the first-class coaches because of the color of their skin. There is a painting somewhere that someone depicted them looking more like animals on stage singing. So they did go through those types of experiences as they went on their first tour. But I always say the young Fisk students who went out to raise funds for the university kept their focus on their mission and also were able to sing their songs and win the hearts of many people.

There have been debates over whether white people singing spirituals is a form of cultural appropriation. And I wonder where you stand on that issue.

As a musician I don’t agree with that because growing up in Ghana, we were taught songs like the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s “Messiah.” The performance of music, I don’t believe should be limited to one specific culture. Because music, rather, brings people together. I would rather encourage people of every culture to learn music of other cultures.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers sang with The Erwins, a Southern gospel group, in February, including the song ” Watch and See.” How often do the Fisk singers sing music other than spirituals and is that generally well received, or are they criticized for not sticking with the music tradition for which they’re known?

I think one of the reasons we won the Grammy is because we sang with other people and the album consists of a variety of music that actually would not be classified as Negro spirituals. The album consisted of country music. We had some blues. We had gospel. We do want to be remembered as an ensemble that sings Negro spirituals but when there are occasions that call for us to sing other types of music and if it fits into our schedule, we are going to do so.

Do you have a favorite spiritual sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers and, if so, which one and why?

I have a lot of favorite spirituals. One of them is ” Lord, I’m Out Here on Your Word.” I like that spiritual because it’s a song that helps me to be committed to my work. A line in the song says “If I die on the battlefield, Lord, I’m out here on your Word.” That is telling me that no matter what goes on, I am out to serve God. And I know he is a faithful God. And I have to be faithful to him as well. If I’m serving him, then no matter what’s going on, I trust him to provide whatever I need to succeed in my work.

Another is “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” I love that song, again, because it gives me the idea that God takes care of us.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 6, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

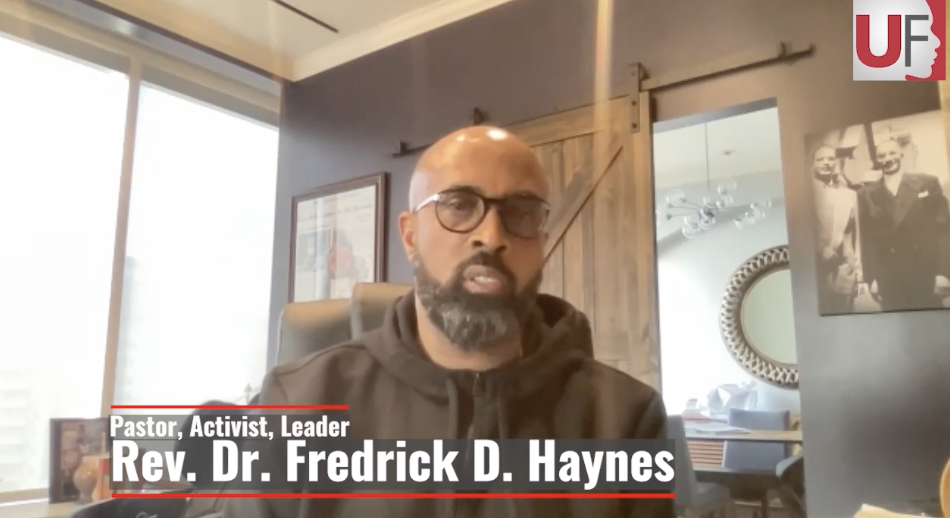

(RNS) — Fannie Lou Hamer was an advocate for African Americans, women and poor people — and for many who were all three.

She lost her sharecropping job and her home when she registered to vote. She suffered physical and sexual assaults when she was taken to jail for her activism. And stories of her struggles reached the floor of the 1964 Democratic Convention — and the nation — when her emotional speech aired on television.

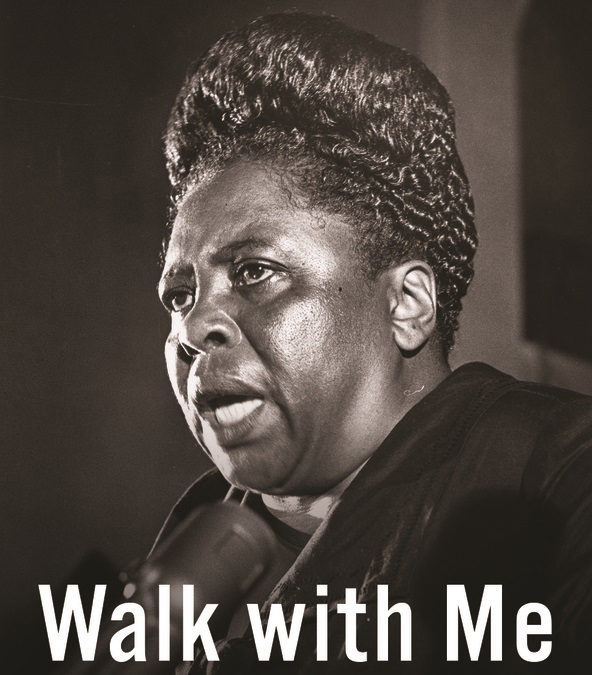

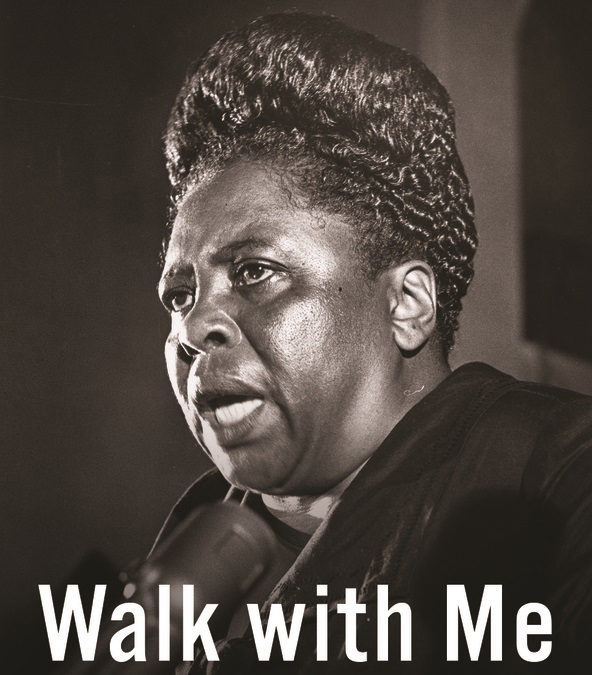

Historian Kate Clifford Larson has written a new book, “Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer,” that reveals details of the faith and life of Hamer, who was born 104 years ago Wednesday (Oct. 6) and died in 1977.

“Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer” by Kate Clifford Larson. Courtesy image

Inspired by young Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers who preached Bible passages about liberation at her church in Ruleville, Mississippi, in 1962, Hamer became a singer and speaker for equal rights and human rights.

“She crawled her way through extraordinarily difficult circumstances to bring her voice to the nation to be heard,” Larson told Religion News Service. “And she knew that she was representing so many people that were not heard.”

Larson spoke to RNS about Hamer’s faith, her favorite spirituals and how music helped the activist and advocate survive.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a biography of Fannie Lou Hamer and how would you describe her as a woman of faith?

I published a book about (Harriet) Tubman and Hamer is so similar to Harriet Tubman, only 100 years later. I decided to start looking into her life and thinking I should do a biography of Hamer. I just became hooked. There were so many similarities, and things I could see in Hamer that I just thought, we need to have a refresher about Fannie Lou Hamer and the strength of her character and how she survived such incredible adversity and found the same kind of solace that Harriet Tubman did — in her faith, in her family and the community — to keep going and fighting and to try to make the world a better place.

It seems she is relatively unknown in many circles despite the credit she’s given by civil rights veterans for her work.

It is curious that she is not well known broadly. And I hope that changes, because I think we need to look back sometimes to see how far we’ve come. And with Hamer, the things that happened to her — she faced the world by confronting that trauma, and that violence, without hate. And the only way she could do that was through her faith, and talking to God and saying: Where are you, what is happening here, give me the strength to carry this weight and to move forward. And she did. She knew hate could really destroy her — that feeling of hating the people that were trying to kill her and subjugate her. She managed to rise above it because she had a greater mission in front of her.

Why did you title the book “Walk With Me”?

The title is from the song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Mississippi, jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her. She asked Euvester to please sing with her because she needed to find strength and she needed God to be with her. So she sang that song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She needed to feel there was something bigger that would help her survive those moments where it wasn’t so clear she would survive. And I found it so powerful that she would do that. She survived that night and was able to get up and walk the next morning.

What other spirituals and gospel songs were particularly important to Hamer as she fought for voting rights and other social justice causes?

One of her favorites is “This Little Light of Mine.” She sang that everywhere, all the time. It’s kind of her anthem. There were some other spirituals, but really, most of the ones she sang a lot during the movement were those crossover folk songs, rooted in Christian spirituals, like “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” She grew up not only in a very strong church environment, the Baptist church, but she grew up in the fields of Mississippi where there were work songs in the fields, call and response songs. Where she grew up was actually the birthplace of the Delta blues music.

She also quoted the Bible to the people she differed with. Were there particular biblical lessons Hamer applied to her fight to help her fellow Black Mississippians?

She used the Bible in many different ways. She used it to shame her white oppressors who claimed also to be Christians, following the path of Christ. She would use the Bible and say: Are you following this path by what you’re doing to me, to my fellow community members and family members? And she used the Bible passages to remind Christian ministers: This is your job, and what are you doing up on that pulpit? You’re telling people to be patient. Well, in the Bible it says stand up and lead people out of Egypt.

You wrote about William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, Hamer’s congregation, throughout the book. What happened there, over the years as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups used it as a place for meetings, classes and rallies?

The church, the ministers participated in the movement and had meetings in that church at great risk to themselves and to the church, and in fact, the church was bombed a couple of times even though the fires were put out, fortunately, very quickly. There were residents in the community that took their lives and put them on the line. They were at great risk, to go to those meetings, to conduct those meetings, to go out and do voter registration drives. It was all centered on the church community because that was really the only community buildings in many of these places where people could meet together to have these discussions.

You said Hamer was at a crossroads as she first listened to those SNCC (pronounced “snick”) activists seeking more people to join their cause.

She experienced trauma, and she had been sterilized against her will — she didn’t give permission — and she had gone through this very deep depression, and it tested her faith. It tested her understanding of the world, and she came out of that and went to this meeting in Ruleville in 1962 and when she heard those young people and their passion and their willingness to put their lives on the line for her, she viewed them as the “New Kingdom.” So it was more than a crossroads for her. It was a moment where she could see the future in these young people, and she called them the “New Kingdom (right here) on earth.” If they were willing to stand up and risk their lives then she could, at 45, 46 years old, stand up herself. That was a crossroads. She made that choice to stand up, publicly, and move forward.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Sep 28, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

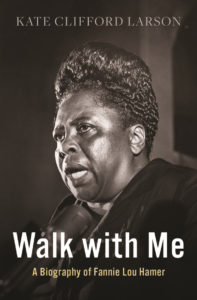

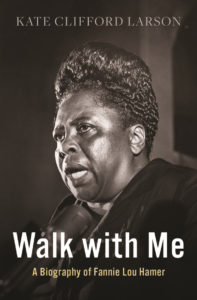

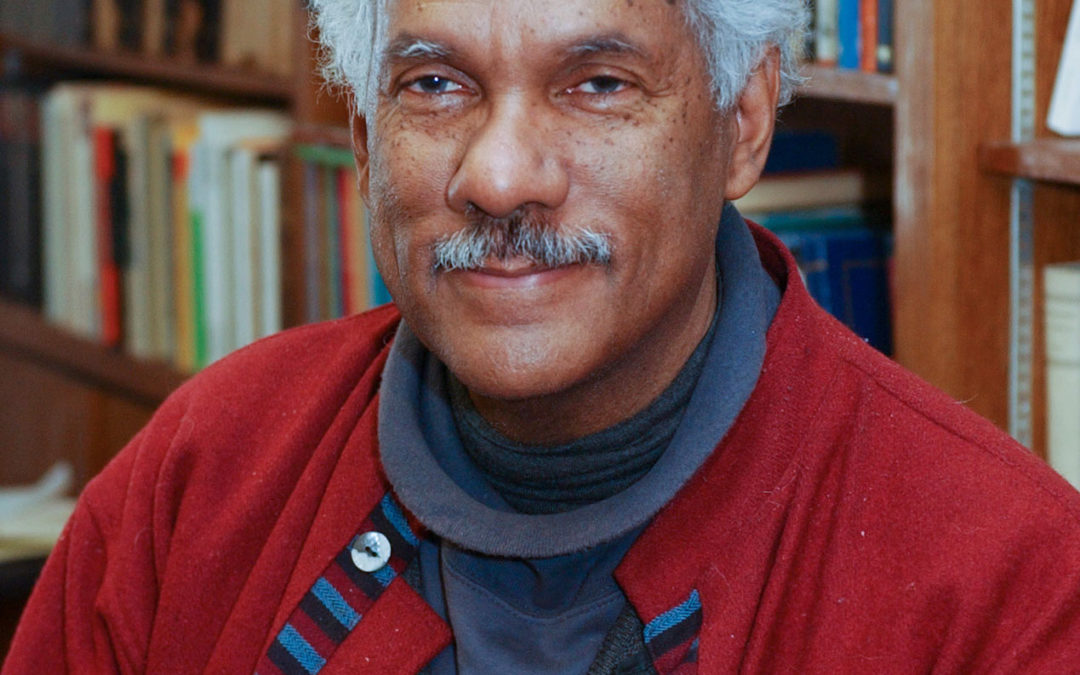

(RNS) — Albert J. Raboteau, an American religion historian who helped students and journalists enhance their understanding of African American religion, has died.

The scholar died on Saturday (Sept. 18) in Princeton, New Jersey, years after being diagnosed with Lewy Body Dementia, Princeton University announced. He was 78.

A Princeton faculty member since the 1980s, Raboteau reached emeritus status in 2013. He chaired the university’s religion department from 1987 to 1992 and was dean of its graduate school from 1992-93.

“Professor Raboteau taught me so much: how to move about the archive, how to trust and be comfortable with my questions, and how to write clearly and with sophistication,” Eddie Glaude Jr., chair of Princeton’s African American studies department, said in a Princeton statement. “His brilliance knew no boundaries. His work helped create an entire field, and he could move just as easily in the fields of literature and film.”

When a book editor came to campus seeking to learn about Raboteau’s next book, a Princeton appreciation noted, the author instead arranged a meeting with the editor and Glaude, leading to the publication of the then-graduate student’s first book.

In addition to his years of mentoring students, Raboteau also gave journalists his perspective on the history of the Black church and contemporary religious attempts to address racism.

At a 2015 Faith Angle Forum discussion, he addressed reporters on the topic ” Forgiveness and the African American Church Experience.” Raboteau said small, face-to-face cross-racial gatherings, such as Bible studies and sharing meals, could be more important than statements of apology about racism by predominantly white denominations.

“What we are as a nation is a collection of disparate stories, an ever exfoliating set of separate stories and what we need to bind us together is to be able to hear the stories of others in face-to-face encounter,” he said. “And that can be sponsored by churches; churches would be a natural place to sponsor that kind of face-to-face contact.”

Raboteau was known for his writings about African American faith, most especially the book “Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South” as well as “Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African American Religious History” and “Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans.”

An “In Memoriam” Princeton tribute described his 2002 book “A Sorrowful Joy” as a volume that reflected “the stakes of the study of African American religious history as a Black man from Bay St. Louis, Mississippi whose father was murdered by a white man before he was born and as a Christian believer whose religious formation took place first in the Roman Catholic Church and in later years in Eastern Orthodoxy.”

Across social media this week, scholars of religion described Raboteau’s personal influence on them.

“For me, Al wasn’t the usual kind of mentor,” tweeted Anthea Butler, professor of religion at the University of Pennsylvania. “He was an ideal to me about both scholarship and spirituality.”

She added, in the last tweet of a thread that seemed to give a nod to his conversion to Orthodox Christianity: “Finally (and not sure if he would a. like this or b. chastise me) but I would pay a lot of money if someone painted Al Raboteau as an icon. For me, he is the patron saint of the study of African American Religion. May he rest in eternal peace and bliss.”

Cornel West, a Princeton emeritus professor who now teaches at Union Theological Seminary, tweeted after the death of his colleague of more than four decades that Raboteau “was the Godfather of Afro-American Religious Studies & the North Star of deep Christian political sensibilities! I shall never forget him!”

Raboteau also was the author of “African American Religion,” a 1999 volume in the “Religion in American Life” series published by Oxford University Press.

He wrote in its first chapter of the historical role of slave preachers and other Black pioneers whose sermons reached free Black people as well as the enslaved.

“The growth of Baptist and Methodist churches between 1770 and 1820 changed the religious complexion of the South by bringing large numbers of slaves into membership in the church and by introducing even more to the basics of Christian belief and practice,” he wrote. “The black church had been born.”

In 2016, when the U.S. Postal Service honored African Methodist Episcopal Church founder Richard Allen with a postage stamp, Raboteau told Religion News Service: “The unwillingness of the Methodists to accept the independent leadership of Black preachers like Allen and the institution of segregated seating led Allen and (clergyman Absalom) Jones to found independent Black churches.”

Late in life, Raboteau continued to interpret lessons of religious and racial history in his 2016 book “American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals and Their Struggle for Social and Political Justice.” He said the book, which included chapters on Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer, was based on his “Religious Radicals” seminar that he taught undergraduate students at Princeton for several years.

Raboteau wrote the book’s introduction as the U.S. marked the 50th anniversary of Alabama’s Selma to Montgomery voting march.

“Memory and mourning combine in prophetic insistence on inner change and outer action to reform systemic structures of racism,” he said.

Raboteau added an anecdote about his own visit to Selma several years before with Princeton alumni and students who visited a museum close to the town’s famous Edmund Pettus Bridge, where activists had once been beaten back by state troopers. On the trip, a Black museum guide who was beaten on the bridge as a young girl encountered a retired white Presbyterian minister who had joined the demonstrations after King requested support from the nation’s clergy.

“It was a moment of shared pathos that transcended time,” he recalled. “For me it was the high point of the trip. I no longer needed to cross the bridge.