by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Mar 10, 2022 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News |

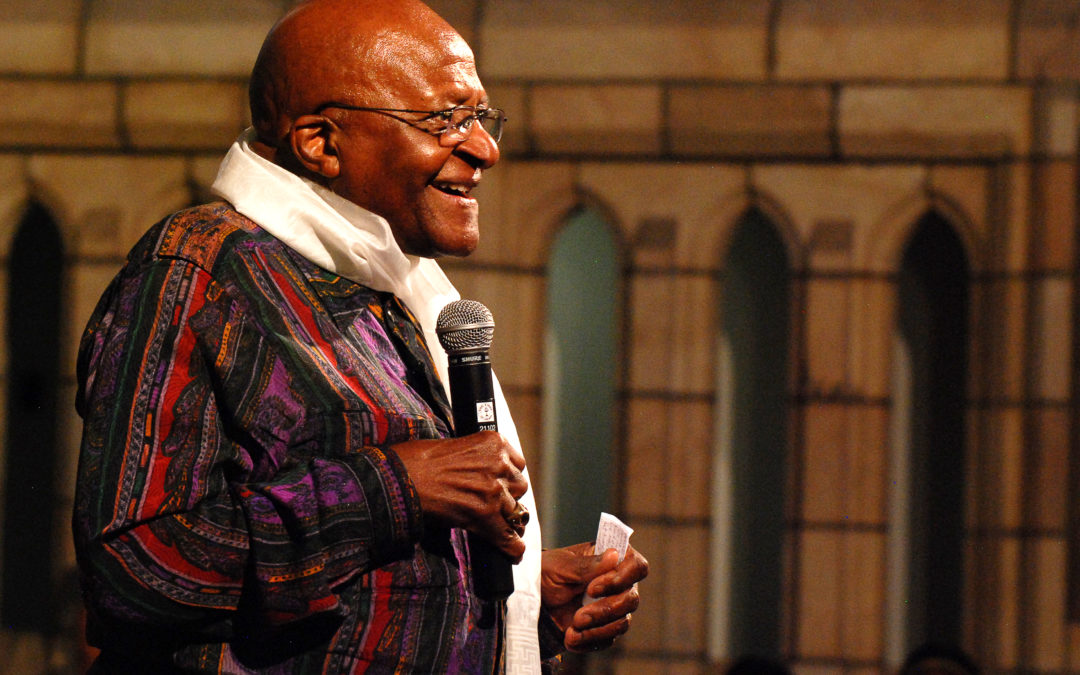

(RNS) — Andrew Young, a former civil rights leader, Georgia congressman and United Nations ambassador, doesn’t use “the Rev.” before his name much.

But the man who directed Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1960s said every stage of his adult life has been a form of ministry.

“I have viewed everything I’ve done as a pastorate,” Young, a onetime small-church pastor, said in a Wednesday (March 2) interview. “I really thought of Congress as my 500-member church.”

Likewise, he recalled making “pastoral calls” and praying with ambassadors representing some of the 150 countries that were then U.N. members.

“My model for almost every job I’ve had has been the model of a pastor servicing a congregation,” Young said. “As the mayor of Atlanta, I just had a million-member church.”

Born into, raised in and ordained by the Congregational Church — now known as the United Church of Christ — he has been a member of Atlanta’s First Congregational Church, a predominantly Black house of worship, since 1961. As he prepares to turn 90 on March 12, he continues to preach there on the third Sunday of each month.

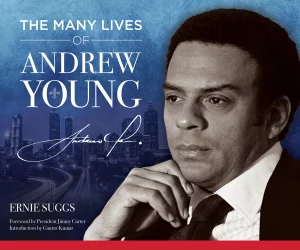

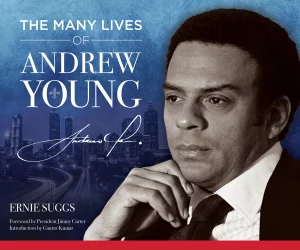

Young is marking his birthday with a four-day celebration from March 9–12, starting with a livestreamed “Global Prayer for Peace” worship service at the Atlanta church, followed by a peace walk, debut of the book “The Many Lives of Andrew Young” and a sold-out gala.

The graduate of what was then called Hartford Theological Seminary spoke to Religion News Service about voting rights battles then and now, religious aspects of the civil rights movement and his memories of working with King.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You intend to preach on peace and reconciliation to mark your 90th birthday. Has Russia’s invasion of Ukraine changed your planned message?

No, it hasn’t. Russia’s invasion has made my message even more central to the problems we’re having around the world. And Russia’s invasion is tragic and it’s even more tragic because it’s televised. But there are similar situations in many, many countries — in Latin America, Africa and other parts of Europe. And in these United States, we’re having a battle to protect the right to vote here in 2022.

You originally had plans to pursue dental school instead of seminary. What made you change your mind and do you ever regret the route you ended up taking?

My father chose dentistry. I never chose dentistry. Even as a 12-year-old, though I might have been working in a dental laboratory that my father wanted me to learn the business, I knew I didn’t want to do anything that confined me to an office. I’ve always been too full of energy and too rambunctious to stay in one place.

Even though you ended up doing ministry of different sorts, you also didn’t stay in one pulpit as some people pursuing ministry do.

We likened the ministry of the civil rights movement to the ministry of Paul and the apostles. Martin had one church. Most of us were ordained. But we pastored communities, cities, and we saw ourselves as pastors to the nation and to the world.

You were a staffer and later president of the National Council of Churches, which has risen and declined in prominence over the years. What do you consider the state of ecumenical relations now?

We have not been able to worship in our congregation for two years now. But we have (online) services, and I usually preach every third Sunday. And I get calls from as far as Switzerland and Tanzania, California, London, where friends somehow find it.

I don’t know what state the organized church is (in). But I think people are becoming and have become more seriously spiritual than at any time in my life.

The book “The Many Lives of Andrew Young” notes that when you entered the civil rights movement, you wrote, “I’ve had about enough of ‘church work’ and am anxious to do the work of the church.” Is there something about the movement’s religious aspects that many may not know?

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

You mentioned voting rights earlier. How do you feel about the state of voting rights, given that you helped lead the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as it sought improved voting rights and now all these years later, it’s still a topic of contention?

I’m shocked that we still have to struggle for the right to vote.

And I think that the changes in Georgia — they are structured now to steal the election. And the voting rights bills that were sent to, I think, some 30 states, they’re the same bill with the same level of corruption and the licensing of voter control. And we don’t have a Congress or a Supreme Court that’s willing to stand up now.

There’s a lot of photos in the new coffee table book about you. Are there any that relate to your religious life, your ministry, that mean the most to you?

Well, actually the one that shows me getting beat up in St. Augustine. That was probably the biggest test of my faith because I ended up leading about 50 people, mostly women and children, into a group of a couple hundred Klansmen who had been deputized by the sheriff to beat us up. I left them on one side of the street and I crossed over, trying to reason with the Klan. I was doing pretty good until somebody came up behind me and hit me with something, and then I didn’t remember anything.

But that was (shortly) before the Congress voted to pass the ’64 Civil Rights Act. And I got up and I went down to the next corner and tried to talk to the Klan on that corner. And fortunately there, when they swung at me, I ducked. And a great big policeman, biggest policeman I’ve ever seen — he was about six-six, six-seven — he walked up and said, ‘Let these people alone. You’re going to kill somebody.’ And he moved the Klan out of the way, and we were able to march.

That was one of the times that nonviolence was really on trial.

You are continuing to preach at First Congregational in Atlanta about every month — often at services featuring jazz music. It doesn’t sound like you’re anywhere near just putting your feet up at age 90.

No. There’s a song, old spiritual, that folks used to sing: “I keep so busy serving my Jesus, I ain’t got time to die.”

I just feel blessed. I have lived a blessed life. You can’t earn it, but I’ve tried to be faithful.

by Jemar Tisby | Feb 11, 2022 | Black History, Headline News, Heritage |

February 1st marks the beginning of Black History Month. Each year U.S. residents set aside a few weeks to focus their historical hindsight on the particular contributions that people of African descent have made to this country. While not everyone agrees Black History Month is a good thing, here are several reasons why I think it’s appropriate to celebrate this occasion.

The History of Black History Month

First, let’s briefly recount the advent of Black History Month. Also called African American History Month, this event originally began as Negro History Week in 1926. It took place during the second week of February because it coincided with the birthdates of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Harvard-trained historian, Carter G. Woodson, is credited with the creation of Negro History Week.

In 1976, the bicentennial of the United States, President Gerald R. Ford expanded the week into a full month. He said the country needed to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

Objections to Black History Month

Black History Month has been the subject of criticism from both Blacks and people of other races. Some argue that it is unjust and unfair to devote an entire month to a single people group. Others contend that we should celebrate Black history throughout the entire year. Setting aside only one month, they say, gives people license to neglect this past for the remaining eleven months.

Despite the objections, though, I believe some good can come from devoting a season to remembering a people who have made priceless deposits into the account of our nation’s history. Here are five reasons why we should celebrate Black History Month.

1. Celebrating Black History Months Honors the Historic Leaders of the Black Community

I have the privilege of living in Jackson, Mississippi which is the site of many significant events in Black History. I’ve heard Myrlie Evers, the wife of slain Civil Rights leader Medgar Evers, speak at local and state events. It’s common to see James Meredith, the first African American student at Ole Miss, in local churches or at community events.

Heroes like these and many more deserve honor for the sacrifice and suffering they endured for the sake of racial equality. Celebrating Black History Month allows us to pause and remember their stories so that we can commemorate their achievements.

2. Celebrating Black History Month Helps Us to Be Better Stewards of the Privileges We’ve Gained

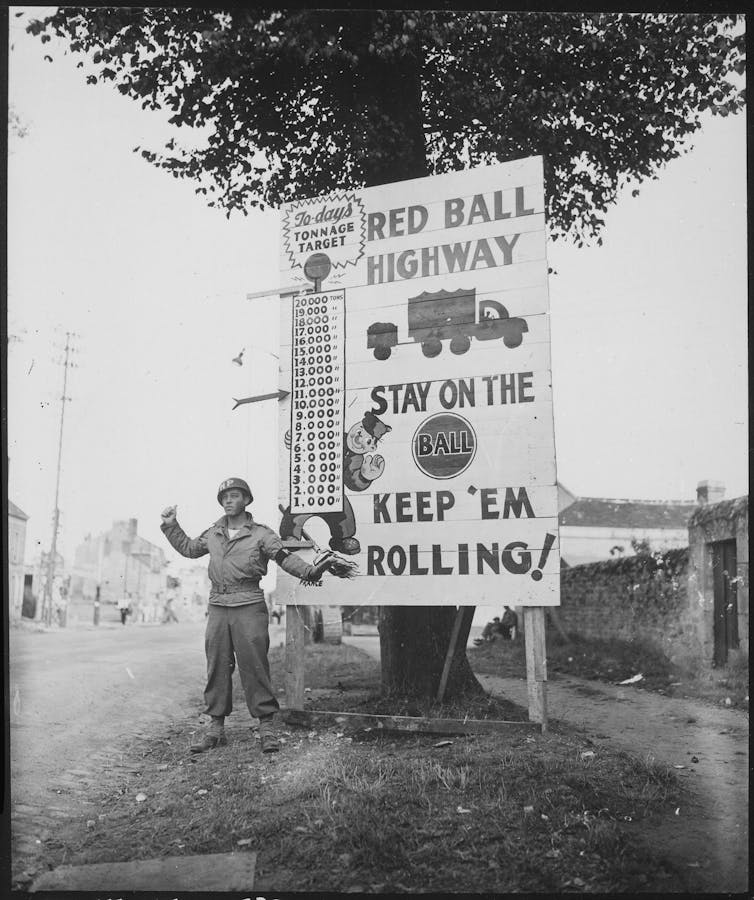

Several years spent teaching middle school students impaled me with the reality that if we don’t tell the old, old stories the next generation, and we ourselves, will forget them. It pained me to have to explain the significance of the Harlem Renaissance and the Tuskegee Airmen to children who had never learned of such events and the men and women who took part in them.

To what would surely be the lament of many historic African American leaders, my students and so many others (including me) take for granted the rights that many people before them sweated, bled, and died to secure. Apart from an awareness of the past we can never appreciate the blessings we enjoy in the present.

3. Celebrating Black History Month Provides an Opportunity to Highlight the Best of Black History & Culture

All too often only the most negative aspects of African American culture and communities get highlighted. We hear about the poverty rates, incarceration rates, and high school drop out rates. We are inundated with images of unruly athletes and raunchy reality TV stars as paradigms of success for Black people. And we are daily subject to unfair stereotypes and assumptions from a culture that is, in some aspects, still learning to accept us.

Black History Month provides the chance to focus on different aspects of our narrative as African Americans. We can applaud Madam C.J. Walker as the first self-made female millionaire in the U.S. We can let our eyes flit across the verses of poetry Phyllis Wheatley, the first African American poet and first African American female to publish a book. And we can groove to soulful jazz and somber blues music composed by the likes of Miles Davis and Robert Johnson. Black History Month spurs us to seek out and lift up the best in African American accomplishments.

4. Celebrating Black History Month Creates Awareness for All People

I recall my 8th grade history textbook where little more than a page was devoted to the Civil Rights Movement. I remember my shock as a Christian to learn about the formation of the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church because in all my years in churches and Christian schools no one had ever mentioned it.

Unfortunately it seems that, apart from intentional effort, Black history is often lost in the mists of time. When we observe Black History Month we give citizens of all races the opportunity to learn about a past and a people of which they may have little awareness.

5. Celebrating Black History Month Reminds Us All that Black History Is Our History

It pains me to see people overlooking Black History Month because Black history—just like Latino, Asian, European, and Native American history—belongs to all of us. Black and White, men and women, young and old. The impact African Americans have made on this country is part of our collective consciousness. Contemplating Black history draws people of every race into the grand and diverse story of this nation.

Why Christians Should Celebrate Black History Month

As a believer, I see racial and ethnic diversity as an expression of God’s manifold beauty. No single race or its culture can comprehensively display the infinite glory of God’s image, so He gave us our differences to help us appreciate His splendor from various perspectives.

God’s common and special grace even work themselves out in the providential movement of a particular race’s culture and history. We can look back on the brightest and darkest moments of our past and see God at work. He’s weaving an intricate tapestry of events that climax in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

And one day Christ will return. On that day we will all look back at the history–not just of a single race but of people from every nation, tribe, and tongue–and see that our Creator had a plan all along. He is writing a story that points to His glory, and in the new creation, His people won’t have a month set aside to remember His greatness. We’ll have all eternity.

Originally published in February 2020

![]()

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.