by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jul 1, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News |

WASHINGTON (RNS) — Well-known names from the world of gospel music and the Black church gathered at the Museum of the Bible to hail the contributions of African American churches and to call for continued efforts toward building unity and bridging divides.

The “Blessing of the Elders,” an awards celebration held Thursday (June 23) just blocks from the U.S. Capitol, specifically honored seven leaders known for their contributions in megachurches, denominational leadership, civil rights, music and religious broadcasting.

The Rev. A.R. Bernard, an honoree and a Brooklyn, New York, pastor, described the Black church, in its varied expressions, as a repository of Black culture in America.

“Embracing Christianity, Blacks didn’t seek to imitate white Christianity — oh no, instead we created a parallel religious culture, our own brand of Christianity with our own hymns, music, style of worship, much influenced by the challenge of slavery,” Bernard said in the museum’s World Stage Theater.

“Christianity gave Blacks hope in the midst of a hopeless situation, and we’re not done yet. I believe the 21st century will see the Black church lead the way to hope and healing in a deeply divided nation.”

One honoree, Bishop Charles E. Blake Sr., the former top leader of the Church of God in Christ, was unable to attend due to medical reasons.

“Bishop Blake wanted me to tell you he was sorry he couldn’t be here,” said Harry Hargrave, chief executive officer of the Museum of the Bible. “He’s coming off of COVID. He’s feeling much better.”

Jon Sharpe, the museum’s chief relations officer, and the Rev. Tony Lowden, pastor of the Georgia church where former President Jimmy Carter is a member, took the stage to explain how the predominantly Black gathering came to be.

Sharpe said he had a vision two decades ago that “the Black church is going to lead spiritual renewal in America.”

The museum executive, who is white, shared his idea over dinner with Lowden, an African American man who had attended a 2020 fatherhood conference at the museum. Lowden said the concept — which Bernard now calls a “movement” — resonated with him.

“There was a move that we had to answer, asking us to come together, go around the nation to talk about how we can bring the Black church together to lead,” Lowden said.

Over the course of the more than three-hour ceremony, coming together and overcoming were recurrent themes.

Over the course of the more than three-hour ceremony, coming together and overcoming were recurrent themes.

“The only way we can go forward now is with ‘love one another,’” said honoree John Perkins, a civil rights veteran and reconciliation advocate, quoting the New Testament book of 1 John and elevating the church as a whole over congregations attended by Black or white people. “‘He that loves knoweth God. He that loveth not knoweth not God.’”

North Carolina pastor Shirley Caesar, an honoree known for her award-winning gospel singing, spoke of worshipping in the “red church,” based on the sacrifice of Jesus, rather than at a Black church or a white church.

And Dallas pastor Tony Evans also spoke of a unified church, saying, “It’s time to go public as the Black church and white church of the kingdom of God, the glory of God and the advancement of his rule in history. It’s time for the church to lead the way.”

Bishop Vashti McKenzie, an honoree and the first woman prelate in the more than 200-year-old African Methodist Episcopal Church, said she accepted her award “on behalf of women who have been pushed to the margins of church culture, yet their gifts continue to make room for them.” As McKenzie stood between her daughter and granddaughter, whom she asked to join her on stage, she urged others to adhere to the biblical admonition to “stand firm.”

Actor and producer Denzel Washington, one of the presenters at the event, noted his spiritual trajectory was shaped by two of the evening’s honorees as they led churches on opposite U.S. coasts — Blake’s West Angeles Church of God in Christ in Los Angeles and Bernard’s Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn.

Actor and producer Denzel Washington, one of the presenters at the event, noted his spiritual trajectory was shaped by two of the evening’s honorees as they led churches on opposite U.S. coasts — Blake’s West Angeles Church of God in Christ in Los Angeles and Bernard’s Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn.

“It’s been an amazing 40-year journey from Bishop Blake’s church, where I first was filled with the Holy Spirit, to tonight,” Washington said, noting that Bernard, “a man of God with a mind of God,” had asked the actor to speak during his time of tribute. “It has been a blessing for all of us to be students of Pastor A.R. Bernard. It’s been a blessing for me personally to have someone that I can talk to, ask questions.”

Between prayers and speeches, a range of Black church music was featured, including from co-hosts BeBe Winans and Erica Campbell — who also harmonized a bit of “Amazing Grace” while awaiting a working teleprompter. Wintley Phipps, Pastor Marvin Winans, Lecrae, the Clark Sisters, Tramaine Hawkins, Fred Hammond and Anthony Brown & group therAPy also performed.

The Blessing of the Elders initiative, which thus far has included a steering committee and been supported by the Museum of the Bible and partnering foundations, individuals and corporate sponsors, is now a not-for-profit corporation that Bernard will chair. In an interview before the gala, he said its next steps could include a documentary, an exhibit or a curriculum about the history of the Black church that would be particularly intended for white churches “to walk a mile in our shoes.”

Steve Green, board chair and founder of the museum, said in a separate interview that a temporary exhibit centered on the Black church — delving more into the subject than what is already featured in its Bible in America permanent exhibit — is a possibility at his facility.

“To be able to do a deep dive within the Black community and the Black church is an exciting opportunity for us to consider because there is a story to be told,” he said.

The evening ended with a blessing of the celebrated elders, but Bishop T.D. Jakes, another honoree, made it clear the concluding prayer should not be solely for the seven people with bios in the program but rather all those who gathered to laud them.

“Perhaps the greatest elders are not on this stage; perhaps the greatest elders are you,” he said. “So if we bless the elders and exclude you from the blessing, we will have missed the opportunity of God’s attention. Because the future is in your hands and your mouth. We’ve all spoken. The next message is on you.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | May 18, 2022 | Headline News, Social Justice |

(RNS) — Soon after a white 18-year-old shooter targeted Black customers of a community grocery store in Buffalo, New York, on Saturday (May 14), the Rev. Denise Walden, executive director of Voice Buffalo, a social justice and equity organization, was coordinating clergy to offer grief counseling and help families immediately and, she hopes, for the foreseeable future.

She was also grieving personally: She knows the families of most of the 10 people killed in the massacre.

“This is going to take more than a week, more than a month, more than six months,” said Walden, a member of the clergy team at First Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, a predominantly Black congregation in Buffalo. “We need long-term solutions and support.”

Walden’s 25-year-old organization is a local chapter of Live Free, a Christian organization that has in recent years focused on preventing community violence, which now has new questions to answer, Walden said, about “the hate that caused this person to come into this community and create such a horrible, violent violation to our community.”

She said more resources are needed to counter hate in general and to cope with the reaction from Buffalo’s Black community. “When tragedy strikes and those things are not in place,” Walden said, “we create an environment that can become even more dangerous because people don’t know what to do to process their grief and their trauma.”

Walden, 42, spoke with Religion News Service about her connections to the people who died on Buffalo’s East Side, who the community has lost and what it needs now.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The massacre on Saturday occurred at a grocery store in your neighborhood. How did you react to the violence that happened there?

I’m a seven-minute walk away from the grocery store. It’s our community store. We’re there regularly. As far as how I reacted, I think I’m still trying to figure that out. For me it was, how do I show up with and in my community, just being a resource and, hopefully, a person to bring some peace and love that are all much needed in this time. And just being as comforting to those who are closest to the pain from this as possible.

You were one of the officiants of a vigil on Sunday outside the Tops grocery store. What words did you find to say?

It was hard. I think we know that there’s a need for comfort. There’s a need for love in our community. And that was the word, reminding people that we are still a strong community; reminding those of us that live here that in spite of this heinous act that we’ve seen, this is still home. This is our home.

You helped notify family members of those who were killed. Was that an unexpected responsibility or have you done that in the past?

That is definitely an unexpected responsibility. I’ve done little bits of it in my clergy capacity. For our organization it’s completely different and completely new. And I’ve never had to show up that way in something so tragic, and also something that is so closely impacting me as well.

The Rev. Denise Walden. Photo via Voice Buffalo

It must have been very difficult.

Difficult doesn’t even describe it. I don’t think that there are words that can describe what was felt by these families and especially when our community is already in such a deep period of grief just still coming out of the pandemic. And then to now have loved ones ripped away from (them) so violently. That’s very difficult news to deliver to anybody.

Some of those lost have been described as church mothers or community mothers and a deacon — people who may have helped others cope when something like this happens in their community.

They are some of the matriarchs and the pillars of our community. They will be missed in ways that I don’t think I can do justice to describing, but who bring joy to this community. They’re the ones who help stand and hold this community together. Check those of us that need to be checked when we need to be checked. They are such an instrumental part of our community. I know some of them have snatched up my kid, like, “Hey, young man, get it together.” That is a huge loss to our entire community.

How will faith leaders address the mental health needs that there are now?

One of the asks that Voice and our partners have been consistently making is for culturally responsive services — people who understand there is some generational trauma here. People that they can feel a sense of community and trust with. There are very big cultural dynamics at play here. We’re working really hard to coordinate faith effortsalongside mental health providers and we’ve had a call out for faith leaders who are also licensed in providing (such) services.

Is that clergy of color who would understand some of the cultural and long-term dynamics here?

Yes, that can do grief counseling, trauma, counseling, all of those typesof things. But we’ve also put out a call to clergy to just be a presence in this community. Just be a presence of peace, a presence of comfort, a presence of love in this community. Because at the end of the day, that’s what’s going to help us start to process. That’s what’s going to help us start to heal.

Before the shooting, what were you planning to do this week?

I was getting ready to go to my sister’s graduation. She’s graduating with her second master’s degree and with honors. We were planning a great family Saturday to just all be together before I was leaving out of town. (But) I need to be here with my family. That’s my actual family, my husband and my children, but I also need to be here with my family that is my community. And so, for that reason, I won’t be traveling, and I’m grateful because she understands.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | May 5, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News |

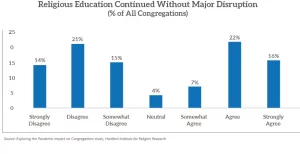

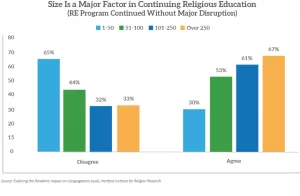

(RNS) — Sunday school and other Christian education programs have suffered during the COVID-19 pandemic, with half of congregations surveyed saying their programs were disrupted.

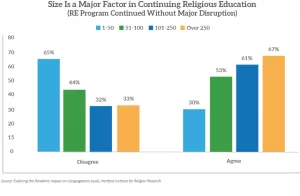

A March 2022 survey by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research found that larger churches with more than 100 people were more successful in maintaining their educational programming for children and youth, often using in-person or hybrid options. Smaller churches, especially those with 50 or fewer attendees, were least likely to say they continued religious education without disruption.

Scott Thumma, principal investigator of the Exploring the Pandemic Impact on Congregations project, said the findings echoed concerns about general education of schoolchildren, where researchers have seen declines in learning over the last two years.

“My sense is that people knew what good robust Sunday school was or what a successful vacation Bible school was,” said Thumma, drawing in part on open-ended comments in the survey. “And they couldn’t parallel that using Zoom or using livestreaming or using take-home boxes of activities. It just wasn’t the same thing. And so when they evaluated it, it just didn’t measure up to what they previously knew as the standard of a good quality religious education program.”

The findings are the third installment in the five-year project, a collaboration with 13 denominations from the Faith Communities Today cooperative partnership and institute staffers.

The new report, “Religious Education During the Pandemic: A Tale of Challenge and Creativity,” is based on responses from 615 congregations across 31 denominations.

Comparing data from 2019, churches surveyed in March 2022 reported that the attendance of their religious education programs had decreased an average of 30% among children younger than 13 and 40% among youth, ages 13-17.

“Analysis showed that those who closed their programs had the greatest decline in involvement even after they restarted,” the new report states. “Likewise, churches that moved religious education online lost a higher percentage of participants than churches who modified their efforts with safety protocols but continued meeting in person either outdoors or in small groups.”

The report notes that it’s not surprising the smallest churches experienced the most disruption in their religious education, given the decline in volunteer numbers and additional stresses on clergy during the pandemic.

“In the smallest churches (1-50 attendees) pastors were most likely in charge of the religious education programs, while for those between 51 and 100 worshippers, volunteers bore the bulk of leadership responsibilities,” according to the report.

Overall, evangelical churches reported experiencing the least disruption to their educational programs, while mainline churches reported the most, followed by Catholic and Orthodox congregations.

Vacation Bible school, long a staple of congregational outreach to local communities, has also been shaken by COVID-19. More than a third (36%) of churches offered such programs prior to the pandemic. That number decreased to 17% in 2020 and jumped back to 36% in the summer of 2021. Slightly less than a third (31%) reported VBS plans for 2022.

While children’s programming was greatly affected by congregational change during the pandemic, adult religious programs saw the smallest decreases compared with pre-pandemic levels, with a quarter growing since 2019 and an almost equal percentage (23%) remaining even.

But, as with children’s programs, churches with 50 or fewer worshippers saw the greatest loss in adult religious education, while those with more than 250 in worship attendance increased their adult programs by an average of 19%.

Some congregations reported moving Sunday school activities to weeknights or vacation Bible schools from weekday mornings to later hours, with mixed results.

“One said they ‘went from a typical 200+ kids to about 35,’” the report notes, and they “’shortened the number of days and moved VBS to the afternoon.’”

Thumma said innovations including intergenerational and kid-friendly programming helped sustain programs for people of all ages in some congregations. These included revamping of the children’s message time during worship to be more inclusive or older members greeting children who run by during Zoom sessions. Some churches called their all-ages activities “messy church” or “Sunday Funday” as they used interactive educational events.

“It becomes, out of necessity, intergenerational because that allows you to have robust energy and lots of people there,” he said. “But it really is directed at the kids being involved in the life of the congregation in a way that isn’t, like, ‘OK, you go to your class’ and ‘you go to your classes,’ and the classes don’t ever mingle.”

Whether creative steps such as new intergenerational activity will continue remains to be seen, Thumma added.

“I think it should because that’s a valuable strategy,” he said. “One of the things that we’ve seen in lots of our research is the more intergenerational the congregation is, the more it has a diversity of any degree, the more likely they are to be vital and thriving.”

The findings in the new report of the project, which is funded by the Lilly Endowment, have an estimated overall margin of error of plus or minus 4 percentage points.

READ THIS STORY AT RELIGIONNEWS.COM

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Mar 10, 2022 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News |

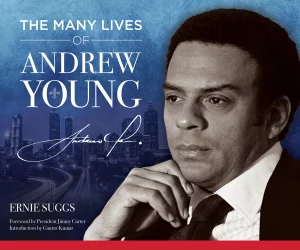

(RNS) — Andrew Young, a former civil rights leader, Georgia congressman and United Nations ambassador, doesn’t use “the Rev.” before his name much.

But the man who directed Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1960s said every stage of his adult life has been a form of ministry.

“I have viewed everything I’ve done as a pastorate,” Young, a onetime small-church pastor, said in a Wednesday (March 2) interview. “I really thought of Congress as my 500-member church.”

Likewise, he recalled making “pastoral calls” and praying with ambassadors representing some of the 150 countries that were then U.N. members.

“My model for almost every job I’ve had has been the model of a pastor servicing a congregation,” Young said. “As the mayor of Atlanta, I just had a million-member church.”

Born into, raised in and ordained by the Congregational Church — now known as the United Church of Christ — he has been a member of Atlanta’s First Congregational Church, a predominantly Black house of worship, since 1961. As he prepares to turn 90 on March 12, he continues to preach there on the third Sunday of each month.

Young is marking his birthday with a four-day celebration from March 9–12, starting with a livestreamed “Global Prayer for Peace” worship service at the Atlanta church, followed by a peace walk, debut of the book “The Many Lives of Andrew Young” and a sold-out gala.

The graduate of what was then called Hartford Theological Seminary spoke to Religion News Service about voting rights battles then and now, religious aspects of the civil rights movement and his memories of working with King.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You intend to preach on peace and reconciliation to mark your 90th birthday. Has Russia’s invasion of Ukraine changed your planned message?

No, it hasn’t. Russia’s invasion has made my message even more central to the problems we’re having around the world. And Russia’s invasion is tragic and it’s even more tragic because it’s televised. But there are similar situations in many, many countries — in Latin America, Africa and other parts of Europe. And in these United States, we’re having a battle to protect the right to vote here in 2022.

You originally had plans to pursue dental school instead of seminary. What made you change your mind and do you ever regret the route you ended up taking?

My father chose dentistry. I never chose dentistry. Even as a 12-year-old, though I might have been working in a dental laboratory that my father wanted me to learn the business, I knew I didn’t want to do anything that confined me to an office. I’ve always been too full of energy and too rambunctious to stay in one place.

Even though you ended up doing ministry of different sorts, you also didn’t stay in one pulpit as some people pursuing ministry do.

We likened the ministry of the civil rights movement to the ministry of Paul and the apostles. Martin had one church. Most of us were ordained. But we pastored communities, cities, and we saw ourselves as pastors to the nation and to the world.

You were a staffer and later president of the National Council of Churches, which has risen and declined in prominence over the years. What do you consider the state of ecumenical relations now?

We have not been able to worship in our congregation for two years now. But we have (online) services, and I usually preach every third Sunday. And I get calls from as far as Switzerland and Tanzania, California, London, where friends somehow find it.

I don’t know what state the organized church is (in). But I think people are becoming and have become more seriously spiritual than at any time in my life.

The book “The Many Lives of Andrew Young” notes that when you entered the civil rights movement, you wrote, “I’ve had about enough of ‘church work’ and am anxious to do the work of the church.” Is there something about the movement’s religious aspects that many may not know?

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

You mentioned voting rights earlier. How do you feel about the state of voting rights, given that you helped lead the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as it sought improved voting rights and now all these years later, it’s still a topic of contention?

I’m shocked that we still have to struggle for the right to vote.

And I think that the changes in Georgia — they are structured now to steal the election. And the voting rights bills that were sent to, I think, some 30 states, they’re the same bill with the same level of corruption and the licensing of voter control. And we don’t have a Congress or a Supreme Court that’s willing to stand up now.

There’s a lot of photos in the new coffee table book about you. Are there any that relate to your religious life, your ministry, that mean the most to you?

Well, actually the one that shows me getting beat up in St. Augustine. That was probably the biggest test of my faith because I ended up leading about 50 people, mostly women and children, into a group of a couple hundred Klansmen who had been deputized by the sheriff to beat us up. I left them on one side of the street and I crossed over, trying to reason with the Klan. I was doing pretty good until somebody came up behind me and hit me with something, and then I didn’t remember anything.

But that was (shortly) before the Congress voted to pass the ’64 Civil Rights Act. And I got up and I went down to the next corner and tried to talk to the Klan on that corner. And fortunately there, when they swung at me, I ducked. And a great big policeman, biggest policeman I’ve ever seen — he was about six-six, six-seven — he walked up and said, ‘Let these people alone. You’re going to kill somebody.’ And he moved the Klan out of the way, and we were able to march.

That was one of the times that nonviolence was really on trial.

You are continuing to preach at First Congregational in Atlanta about every month — often at services featuring jazz music. It doesn’t sound like you’re anywhere near just putting your feet up at age 90.

No. There’s a song, old spiritual, that folks used to sing: “I keep so busy serving my Jesus, I ain’t got time to die.”

I just feel blessed. I have lived a blessed life. You can’t earn it, but I’ve tried to be faithful.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Feb 22, 2022 | Commentary, Faith & Work, Headline News |

WASHINGTON (RNS) — The Rev. Melech E.M. Thomas attended two seminaries and graduated from the second, a historically Black theological school, in 2016.

That academic journey has put him in the pulpit of an African Methodist Episcopal Church in North Carolina.

But his pursuit of a Master of Divinity degree also left him about $80,000 in debt.

“The tuition was less, but I still had to live,” he said, describing other seminary-related costs after his transfer from Princeton Theological Seminary to the Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology at Virginia Union University. “I’m in seminary full time. And I got to make sure I’m paying rent, that I’m eating, all those other expenses.”

Thomas traveled to the nation’s capital in early February for a meeting with other graduates, leaders and students of Black theological schools to discuss possible solutions for the disproportionately high debt of Black seminarians.

Delores Brisbon, leader of the Gift of Black Theological Education & Black Church Collaborative, said it’s important for leaders to understand the sacrifices being made by students who pursue seminary degrees in historically Black settings.

“We need to address this issue of debt,” she said, opening the collaborative’s two-day event, “and determine what we’re going to do about it.”

According to data from the Association of Theological Schools, debt incurred by Black graduates in the 2019-2020 academic year averaged $42,700, compared with $31,200 for white grads.

Data shows 30% of Black graduates in the 2020-2021 academic year had debt of $40,000 or more, compared with 11% of white graduates.

Thomas, 34, said his debt, necessary to achieve his degree and gain ordination, has led to a church appointment that “pays me enough to pay rent,” but not his other living expenses. Yet, Thomas said he knows he’s in a better situation than some other graduates of historically Black seminaries.

“I’m grateful,” he said. “But it’s extremely tough.”

The collaborative includes five Black theological schools — Hood Theological Seminary, Interdenominational Theological Center, Payne Theological Seminary, Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology and Shaw University Divinity School. Lilly Endowment Inc. has given three grants between 2014 and 2020 totaling $2.75 million to the In Trust Center for Theological Schools to help facilitate coordination and increased mutual support between the schools, including the recent meeting about student debt.

The Rev. Jo Ann Deasy, co-author of a 2021 report on the ATS Black Student Debt Project, told the dozens gathered at a Washington hotel that the project came about as researchers discovered how “Black students were just burdened by debt more than any others.”

She said ATS is seeking to help change perceptions about what the project calls the “financial ecology of Black students” as seminarians seek training to become religious leaders, churches hope to hire them and theological institutions consider expanding financial networks to aid them.

“We’re trying to help people shift their understanding of finances from really individual responsibility to a broader systemic understanding of how finances operate in our communities and in our churches,” she said. “This is just a part of that shift toward understanding that it’s not the students’ fault but that this is a bigger issue that we need to address together.”

The report described “money autobiographies” of students who sought financially stable circumstances as they attended theological schools, whether historically Black, white or multiracial.

“They noted the disparities in financial support, particularly from congregations and denominations, between themselves and their White colleagues, a disparity that was often not seen or acknowledged by their peers or the institutions they attended,” the report states.

The average annual tuition for an M.Div. — before any scholarships are considered — is $13,100 for free-standing Protestant schools and $12,500 for Protestant schools related to a college or university. Chris Meinzer, senior director and COO of ATS, said that, on average, it takes students about four years to complete an M.Div. degree.

Seminary graduates who attended the Washington event spoke of having few scholarship options and having to take out loans to pay for expenses including or beyond tuition.

“It’s the cost of being enrolled and the cost of student fees along with your books,” said the Rev. Jamar Boyd II, senior manager of organizational impact at the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, which supports African American ministries. Depending on the class and the number of books required, it could amount to as much as $600 to $700 in a semester, said Boyd, 27, a graduate of Virginia Union University’s theological school.

“If you’re a full-time student taking three or four classes, that’s a paycheck,” he said.

Minister Kathlene Judd, a theologian in residence at an Evangelical Lutheran Church in America congregation in North Carolina, said she eventually chose debt over the mental stress of working, studying and supporting a family at the same time.

She worked in information technology as she went through seminary and continues that career as she pays off her debts after originally hoping to pay for seminary without taking out loans.

“If I’m being fully transparent, I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” said Judd, 38, who graduated from Shaw University Divinity School in 2020.

She said it was a “big decision” to borrow money to continue the education she felt God called her to pursue.

“But honestly, it came down to my mental and emotional health,” she said.

Many students and grads, like Judd, are at least bivocational.

The Rev. Lawrence Ganzy Jr. is in his fourth year at Hood Theological Seminary, where he attends a track that allows him to pastor an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in South Carolina while taking classes on Friday nights and Saturdays. During the week, he’s an admissions officer for Strayer University.

Prior to seminary, his work through the Carolina College Advising Corps, a government program for University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill graduates to counsel low-income high school students, helped him afford the start of his theological studies.

“That paid for my first year of seminary,” said Ganzy, 26. “Then when I got to the next year, that money was gone.”

Keynoting the opening night of the collaborative meeting, the Rev. Michael Brown, president of Payne Theological Seminary in Wilberforce, Ohio, pointed to the portion of the Lord’s Prayer that says “forgive us our debts as we forgive those who are indebted to us” in the Gospel of Matthew.

“Debt keeps us chained to the past and it doesn’t open up possibilities for the future,” he said, “and so the idea of the forgiveness of debt in the Lord’s Prayer is that it releases you to do things for God.”

During the event, graduates spoke of the additional financial struggles they faced, such as debt affecting their credit scores as they try to purchase a car and escalating rent, sometimes in historically Black neighborhoods that have been gentrified.

Brisbon pointed out that Black theological schools may have small endowments and may not get support from their alumni, in part because of the often-lower salaries received by their graduates.

“Black preachers may love their school as much as somebody else but they can’t give money that they don’t have,” she said.

The ATS report noted that a 2003 Pulpit & Pew study found that, on average, Black clergy salaries were about two-thirds those of white clergy. In a 2019 Christian Century essay, scholars noted that a study by the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference found that one-third of Black pastors believed they were “fairly and adequately compensated as a professional” while 67% said that they had “particular financial stress” at that current time.

The Rev. Leo Whitaker, executive minister of the Baptist General Convention of Virginia, told Religion News Service that some clergy in the more than 1,000 churches in his Black state denomination are often “bivocational if not trivocational” to make ends meet, especially when they are located in a region like the state’s Northern Neck rather than the city of Richmond.

Whitaker suggested to collaborative members that they look to U.S. government programs that offer debt forgiveness to educators and doctors who serve in needy communities, noting they should offer the same for seminary grads. He hopes collaborative members will discuss his idea with seminary and education officials.

“You’re serving a stressed community and you’re financially stressed yourself without the ability to make the necessary funds and it’s not about them having a choice of where they choose to serve,” he said, noting that Methodist bishops appoint clergy and Baptist clergy go where congregations have called them to serve. “In ministry our location is not always assigned to us by choice.”

Bishop Teresa Jefferson-Snorton of the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, a historic Black denomination, said laypeople and clergy may not be aware of the sacrifices made by seminarians and recent graduates as they pay seminary tuition that is far more than what she paid 40 years ago.

“Most of our highly organized denominations don’t really have a grasp on what they are actually doing or not doing to support theological education,” Jefferson-Snorton added. “Although in many cases we promote it, we encourage it. But we don’t resource it and I think that needs to be brought to the attention of the church.”

RNS receives funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. RNS is solely responsible for this content.

Over the course of the more than three-hour ceremony, coming together and overcoming were recurrent themes.

Over the course of the more than three-hour ceremony, coming together and overcoming were recurrent themes. Actor and producer Denzel Washington, one of the presenters at the event, noted his spiritual trajectory was shaped by two of the evening’s honorees as they led churches on opposite U.S. coasts — Blake’s West Angeles Church of God in Christ in Los Angeles and Bernard’s Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn.

Actor and producer Denzel Washington, one of the presenters at the event, noted his spiritual trajectory was shaped by two of the evening’s honorees as they led churches on opposite U.S. coasts — Blake’s West Angeles Church of God in Christ in Los Angeles and Bernard’s Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn.

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.

That it was grounded in social gospel and in biblical theology. That Martin Luther King did his doctorate in the time of people like (theologians) Paul Tillich and Reinhold Niebuhr, and he carried Howard Thurman’s little book “Jesus and the Disinherited” in his briefcase all the time. And during the civil rights movement, we had worship every night.