by Ben Finley, Associated Press | Oct 15, 2021 | Black History, Headline News, Heritage |

Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, holds a one-cent coin from 1817 on Wednesday Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. The coin helped archaeologists confirm that a recently unearthed brick-and-mortar foundation belonged to one of the oldest Black churches in the United States. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (AP) — The brick foundation of one of the nation’s oldest Black churches has been unearthed at Colonial Williamsburg, a living history museum in Virginia that continues to reckon with its past storytelling about the country’s origins and the role of Black Americans.

The First Baptist Church was formed in 1776 by free and enslaved Black people. They initially met secretly in fields and under trees in defiance of laws that prevented African Americans from congregating.

By 1818, the church had its first building in the former colonial capital. The 16-foot by 20-foot (5-meter by 6-meter) structure was destroyed by a tornado in 1834.

First Baptist’s second structure, built in 1856, stood there for a century. But an expanding Colonial Williamsburg bought the property in 1956 and turned it into a parking lot.

First Baptist Pastor Reginald F. Davis, whose church now stands elsewhere in Williamsburg, said the uncovering of the church’s first home is “a rediscovery of the humanity of a people.”

“This helps to erase the historical and social amnesia that has afflicted this country for so many years,” he said.

Colonial Williamsburg on Thursday announced that it had located the foundation after analyzing layers of soil and artifacts such as a one-cent coin.

For decades, Colonial Williamsburg had ignored the stories of colonial Black Americans. But in recent years, the museum has placed a growing emphasis on African-American history, while trying to attract more Black visitors.

Reginald F. Davis, from left, pastor of First Baptist Church in Williamsburg, Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist, and Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, stand at the brick-and-mortar foundation of one the oldest Black churches in the U.S. on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. Colonial Williamsburg announced Thursday Oct. 7, that the foundation had been unearthed by archeologists. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

The museum tells the story of Virginia’s 18th century capital and includes more than 400 restored or reconstructed buildings. More than half of the 2,000 people who lived in Williamsburg in the late 18th century were Black — and many were enslaved.

Sharing stories of residents of color is a relatively new phenomenon at Colonial Williamsburg. It wasn’t until 1979 when the museum began telling Black stories, and not until 2002 that it launched its American Indian Initiative.

First Baptist has been at the center of an initiative to reintroduce African Americans to the museum. For instance, Colonial Williamsburg’s historic conservation experts repaired the church’s long-silenced bell several years ago.

Congregants and museum archeologists are now plotting a way forward together on how best to excavate the site and to tell First Baptist’s story. The relationship is starkly different from the one in the mid-20th Century.

“Imagine being a child going to this church, and riding by and seeing a parking lot … where possibly people you knew and loved are buried,” said Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist. She is also board president of the Let Freedom Ring Foundation, which is aimed at preserving the church’s history.

Colonial Williamsburg had paid for the property where the church had sat until the mid-1950s, and covered the costs of First Baptist building a new church. But the museum failed to tell its story despite its rich colonial history.

“It’s a healing process … to see it being uncovered,” Harshaw said. “And the community has really come together around this. And I’m talking Black and white.”

The excavation began last year. So far, 25 graves have been located based on the discoloration of the soil in areas where a plot was dug, according to Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology.

Gary said some congregants have already expressed an interest in analyzing bones to get a better idea of the lives of the deceased and to discover familial connections. He said some graves appear to predate the building of the second church.

It’s unclear exactly when First Baptist’s first church was built. Some researchers have said it may already have been standing when it was offered to the congregation by Jesse Cole, a white man who owned the property at the time.

First Baptist is mentioned in tax records from 1818 for an adjacent property.

Gary said the original foundation was confirmed by analyzing layers of soil and artifacts found in them. They included an one-cent coin from 1817 and copper pins that held together clothing in the early 18th century.

Colonial Williamsburg and the congregation want to eventually reconstruct the church.

“We want to make sure that we’re telling the story in a way that’s appropriate and accurate — and that they approve of the way we’re telling that history,” Gary said.

Jody Lynn Allen, a history professor at the nearby College of William & Mary, said the excavation is part of a larger reckoning on race and slavery at historic sites across the world.

“It’s not that all of a sudden, magically, these primary sources are appearing,” Allen said. “They’ve been in the archives or in people’s basements or attics. But they weren’t seen as valuable.”

Allen, who is on the board of First Baptist’s Let Freedom Ring Foundation, said physical evidence like a church foundation can help people connect more strongly to the past.

“The fact that the church still exists — that it’s still thriving — that story needs to be told,” Allen said. “People need to understand that there was a great resilience in the African American community.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 12, 2021 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Heritage |

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in 2016. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

(RNS) — A century and a half ago, nine young men and women embarked on a trip from Fisk University, establishing a tradition of singing spirituals that both funded their Nashville, Tennessee, school and introduced the musical genre to the world.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, based at the historically Black university founded by the abolitionist American Missionary Association and later tied to the United Church of Christ, started traveling 150 years ago on Oct. 6, 1871. They since have continued to sing so-called slave songs such as “Down by the Riverside” and “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and stood on stages from New York’s Carnegie Hall to Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium.

Musical director Paul Kwami has led the group since 1994 and sang with it when he was a Fisk student in the 1980s. Then and now he views the songs as not only expressions of the religious beliefs of enslaved people, but also of the original singers and the ones who continue to sing today.

“There are songs like ‘Ain’t-a That Good News,’ which is a song that talks about having a crown in heaven, having a robe in heaven,” said Kwami, a member of a nondenominational Full Gospel church in Nashville. “Well, they’ve never been to heaven, but then they’re singing about heaven — that’s an expression of faith.”

Kwami, a native of Ghana, in West Africa, talked with Religion News Service about how the ensemble began, who should sing spirituals and which of the songs are his favorites.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in Jubilee Hall at Fisk University on Oct. 29, 2020. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers won their first Grammy in 2020 for an album that celebrates almost a century and a half of music. What does that say about the endurance of the group and the music that they have sung for so long?

The album was actually produced on the (university’s) 150th anniversary. But then, of course, it is the Fisk Jubilee Singers who won the Grammy, which actually makes me realize that people still recognize who the Fisk Jubilee Singers are. And people still appreciate the music. Additionally, people realize Fisk Jubilee Singers are artists and do not limit themselves to just Negro spirituals. There’s versatility in our choice of music when we have celebrations.

How do you define spirituals, and differentiate them from other forms of African American music sung in Black churches and beyond?

The Negro spirituals are songs that were created by the slaves during their time of slavery. But when we talk about music like jazz or blues or gospel, those genres of music came long after the Negro spirituals were established. And some people even say these other forms of music were birthed out of the Negro spirituals.

When we talk about the Negro spiritual and, say, gospel music, the performance styles are completely different. Gospel music simply deals with church music with a lot of instrumental accompaniment, clapping, a lot of improvisation. But with the Negro spiritual, even though there may be some improvisation, it doesn’t involve a lot of improvisation. Traditionally, Negro spirituals don’t call for instrumental accompaniment.

When the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing, the music is a cappella. The original Fisk Jubilee Singers transformed the Negro spiritual into an art form or concert spiritual. And because of that, clapping, for example, is not recognized as part of a performance of Negro spirituals.

Spirituals are known for their layers of meaning, some of which were hidden to slave masters. Can you give an example of one that is often sung by Fisk Jubilee Singers that reflects that?

One we often sing is “Steal Away to Jesus.” (One) meaning is that we will run away to the North — because we’re stealing away to Jesus — and Jesus was referring to a place of freedom.

When George White, a music professor and Fisk’s treasurer, decided to have singers from the school perform the spirituals for white audiences as fundraisers, was his idea supported by many or was it controversial or both?

To leave Fisk with a group of students to go on a tour, singing to raise money — that was opposed. The administration at Fisk at that time did not believe he would succeed. They thought this was more of an experimental adventure because no one had ever done that. He was not sure of how audiences would receive Black young people singing so he taught them to sing Western (and European) classical music with a hope that would be more attractive to the various audiences. The Fisk Jubilee Singers were also not willing to sing the Negro spirituals because those songs were very sacred to them. But eventually, they started singing the Negro spirituals to the delight of their audiences.

The spirituals were “concertized” for performance for these fundraisers. Do you think anything was lost as the songs moved from the field where slaves had labored to concert halls where people paid to hear them sung?

I don’t think anything was lost. I read a quote by one of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers, and in this book he transcribes some of the songs they sang. I look at the melodies and they’re the same melodies we sing except the arrangements may be different.

How were the singers received at a time when slavery had just ended and African Americans were not welcome in many venues that were segregated?

Originally, they were not well received. There are accounts where people would go into the concerts, listen to the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing and not even give donations. There are accounts of Fisk Jubilee Singers going into hotels and hotel owners, realizing they were Black people, turned them away, wouldn’t give them a place to sleep or food to eat. There was a time when George White was able to purchase first-class coach (train) tickets for them but they were refused admittance into the first-class coaches because of the color of their skin. There is a painting somewhere that someone depicted them looking more like animals on stage singing. So they did go through those types of experiences as they went on their first tour. But I always say the young Fisk students who went out to raise funds for the university kept their focus on their mission and also were able to sing their songs and win the hearts of many people.

There have been debates over whether white people singing spirituals is a form of cultural appropriation. And I wonder where you stand on that issue.

As a musician I don’t agree with that because growing up in Ghana, we were taught songs like the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s “Messiah.” The performance of music, I don’t believe should be limited to one specific culture. Because music, rather, brings people together. I would rather encourage people of every culture to learn music of other cultures.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers sang with The Erwins, a Southern gospel group, in February, including the song ” Watch and See.” How often do the Fisk singers sing music other than spirituals and is that generally well received, or are they criticized for not sticking with the music tradition for which they’re known?

I think one of the reasons we won the Grammy is because we sang with other people and the album consists of a variety of music that actually would not be classified as Negro spirituals. The album consisted of country music. We had some blues. We had gospel. We do want to be remembered as an ensemble that sings Negro spirituals but when there are occasions that call for us to sing other types of music and if it fits into our schedule, we are going to do so.

Do you have a favorite spiritual sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers and, if so, which one and why?

I have a lot of favorite spirituals. One of them is ” Lord, I’m Out Here on Your Word.” I like that spiritual because it’s a song that helps me to be committed to my work. A line in the song says “If I die on the battlefield, Lord, I’m out here on your Word.” That is telling me that no matter what goes on, I am out to serve God. And I know he is a faithful God. And I have to be faithful to him as well. If I’m serving him, then no matter what’s going on, I trust him to provide whatever I need to succeed in my work.

Another is “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” I love that song, again, because it gives me the idea that God takes care of us.

by Anthony Jones II | Oct 10, 2021 | Headline News, Prayers & Devotionals |

The Parable of the Prodigal Son follows the aloof youngest Son of a wealthy household. Convinced of his own maturity and confined to his father’s way of life, the Son asks his father for his inheritance early in order to move to the city and create a life for himself. After magnificently failing in this endeavor, the Son returns home to his father and asks for his forgiveness. In response to his child’s rebellion, the father welcomes him back home with open arms and even throws a decadent celebration to commemorate his return.

When reading this parable, most people identify with the Son. The metaphor of the story lends itself to such an interpretation with the father representing the unconditional forgiveness of God and the Son representing the hubris and fallible nature of humanity. However, this story is more complex than it might seem at first glance. When viewed again we can learn a valuable lesson about forgiveness from this parable. One of the main themes throughout Jesus’ ministry on Earth is the idea of forgiveness. In one of his most famous speeches, Jesus talks at length about how you should treat people who have wounded you in the past. For instance in Matthew 5:49-50, Jesus says:

but I tell you, do not resist an evil perSon. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to the other cheek also. And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well.

Only a few verses later, Jesus goes on to clarify his position on retaliation even further. In Matthew 5:44, he gives his timeless instruction to love your neighbor as yourself, an idea echoed in Mark 11:31 when asked to discuss which commandments are most important. To Christ, the desire for revenge and retaliation in the face of adversity are distractions from witnessing the humanity present in that perSon and treating the conditions that gave rise to the conflict in the first place. Instead of returning force with force, Christian conflict resolution might look more like turning the other cheek or donating your coat to someone who needs it more than yourself. It would also look like the open and loving acceptance of a father recovering his prodigal Son.

The Father in The Story of the Prodigal Son is the true role model of this story, not the Son. It is the Father who provides the listener with a vision for what forgiveness is. Throughout the end of the parable, the older brother begins to take a more prominent role in the story, asking questions that an observer might and second-guessing his father’s choices. He blames his brother for squandering his wealth and grows jealous in response to the warm welcome his brother received from his father. This contrasts with the Father who disregards his Son’s failings and welcomes him back into his household despite them. This distinction is important because it shows us the difference between the love of man and Christ’s forgiveness. Human relationships can be eroded by breaches in trust and changes in character. A relationship with Christ is constant, motivated by love that transcends broken trust and perSonal pain. This is not to say that we should stick by every perSon who hurts us. What Jesus shows in the Parable of the Prodigal Son is to be like the father. Despite all of the time and money wasted by his Son, the father chooses to accept him back when met with a genuine apology.

It is very easy to forgive someone who is close to you or someone who hurt you once in the distant past but forgiveness is not just an action. It is a mindset to treat people with love regardless of your opinion of them. This idea does not just extend to our close friends and relatives. It also applies to race, gender, and even nationality. As Christians, we are called to grow God’s kingdom. That is very hard to do when petty grudges and bottled resentment not only promotes self-righteous gatekeeping but also drives internal divisions within the Church. First and foremost, we must remember that regardless of our history we were all the Prodigal Son. When put in the father’s position we know what we should do, but what truly matters is if we act like our heavenly Father.

by James Alexander, Jr. | Oct 8, 2021 | Faith & Work, Headline News |

In church, we often hear people make reference to “being a good steward over what God has given us.” But do we really know what that means?

Many would argue that the Bible talks more about money and stewardship than almost anything else. That suggests to us that what God has to say about money is pretty important.

Yes, there are more ways of practicing stewardship than ways that involve money, but money is what people struggle with most. Let’s address God’s posture toward our finances this particular article—we’ll save parts II and III on personal finance tips and church finances for another time.

First, many Christians have an incorrect biblical understanding about money. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve simply mentioned money and a Christian said, “Don’t talk to me about money. You know the Bible says that money is the root of all evil!” Well… no, it doesn’t. First Timothy 6:10 says that “the LOVE of money is the root of all [kinds of] evil.” And that makes a big difference. Money itself isn’t evil. Money is necessary. It’s the love of money that makes people do evil things to acquire more money. Essentially, the Bible is warning us not to make money our idol or god. If Christians spend their time avoiding money conversations, how can we expect to acquire any money or manage the money we have well?

So how does the Bible say we should manage money? Luckily, Jesus gives us a parable (a short story that makes a point) about managing money! But it might not be quite what you realized when you heard it in Sunday School or heard it preached…

Matthew 25:14–30 and Luke 19:12–28 are parables about financial investment that Jesus tells to illustrate what the kingdom of God is like. Yes, you read that right. Jesus tells a story about stewardship and managing currency (fittingly called “talents,” making it translatable to non-monetary gifts as well) to illustrate what God’s rule is like. The stories have some minor differences, so I’ll stick with the more popular version in Matthew 25.

Briefly, the story goes like this: a man has three people that work for him. (We can call them servants or employees.) He leaves them five talents, two talents, and one talent, respectively, while he travels to another country. (A talent could be interpreted as a way of making money or money itself. For this, let’s just say a talent is worth $10,000.) When he comes back after a long time, the first employee now has ten talents ($100,000), the second has four talents ($40,000), and the last one gives his talent ($10,000) back to his employer. The employer rewards the two servants that made him money, but calls the other one wicked and “cast[s] the unprofitable servant into outer darkness” where it says there’ll be “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 25:30, KJV). Yeah… he sends the unprofitable “wicked” servant to (symbolic) hell.

Briefly, the story goes like this: a man has three people that work for him. (We can call them servants or employees.) He leaves them five talents, two talents, and one talent, respectively, while he travels to another country. (A talent could be interpreted as a way of making money or money itself. For this, let’s just say a talent is worth $10,000.) When he comes back after a long time, the first employee now has ten talents ($100,000), the second has four talents ($40,000), and the last one gives his talent ($10,000) back to his employer. The employer rewards the two servants that made him money, but calls the other one wicked and “cast[s] the unprofitable servant into outer darkness” where it says there’ll be “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matthew 25:30, KJV). Yeah… he sends the unprofitable “wicked” servant to (symbolic) hell.

Whoa! That’s what the kingdom of God is like? According to Jesus—yep. But let’s unpack what this story is trying to tell us. It’s not saying that if we don’t make money (for God or ourselves), we’re going to hell. It’s something much more subtle and fundamental. So here are the three reasons the employer (who presumably represents God in this parable) is upset and what God is trying to tell us.

1. “Talents” lose value over time unless you grow them.

One of the first things that any good finance class will teach you is the time value of money, which simply means that money today is worth more than the same amount in the future. For some, this concept can be hard to understand, but trust me, it’s true. Money today can be invested sooner and gain more interest, so it is always worth more if used. And that’s before we consider inflation. In telling the story, Jesus is pointing out that the talents/money/earning potential that the master gave the servants was a gift that the master expected to be used for his benefit. (Sound familiar?) Jesus is clearly indicating that humans are God’s servants and that He expects us to use our talents (monetary and non-monetary) to His benefit. (The text doesn’t say “after a long time” he “settled accounts with them” for no reason; it’s symbolic of our lifetimes (Matthew 25:19, NIV).)

2. The servant wastes the talent that the master gave him.

I did say it’s only worth more if used. That’s why the Lord was so upset—the servant didn’t use the talent he was given. That means he not only wasted the talent itself (because it is worth less now than it was when he gave it to him), but also wasted all of that time that he had the talent. Imagine how much that single talent could have grown and been enhanced, but by hiding it instead of using it, he robbed it of its value. Unfortunately, some of us are guilty of doing the same thing with God because, like the servant in the stories, we’re afraid of messing up with the talent we have. This story warns us that the way to really mess up is to hide our talents and money out of fear and not utilize them for God’s glory

3. The servant/employee doesn’t put in any effort.

The biggest tragedy of this parable is that it didn’t have to end up that way for the third servant. The master points out that even if he feared him, hiding his talent (i.e., putting his money under a mattress) was the worst thing he could’ve done with it. He says, “You could have at least put my money in the bank so that it could have gained interest!” (Credit unions are also a great option these days.) This suggestion serves to tell us that even a little growth is better than no growth. Yet for some reason, many Christians think that as long as we present God with what He gave us, we’ll be fine. Not so. If we don’t help grow God’s kingdom, even a little bit, then it is as if He had not given us any gifts or talents to begin with. Putting the money in the bank was something simple that did not take much effort; how often do we not put in the effort to speak with someone about God or to pay our tithes and give our offerings? When we don’t put in the effort required to grow what God has given us, we are being the wicked servant Jesus warned us about.

In conclusion, many Christians erroneously believe that if they had more money, they would do better with it. Others say that when they make more money, they’ll pay their tithes, yet when a raise comes, they simply spend more money and never tithe. Based on the Scripture, if we did a better job of managing the little that we had, not only would we have more as a result of our good stewardship, but God would bless us with more. This is what I believe Jesus means when He says, “For whoever has will be given more … Whoever does not have, even what they have will be taken from them” (Matthew 25:29, NIV). To God, if we don’t put forth the effort to grow a little, then we won’t have the “talent,” skill, or practice needed to manage something greater.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 6, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

(RNS) — Fannie Lou Hamer was an advocate for African Americans, women and poor people — and for many who were all three.

She lost her sharecropping job and her home when she registered to vote. She suffered physical and sexual assaults when she was taken to jail for her activism. And stories of her struggles reached the floor of the 1964 Democratic Convention — and the nation — when her emotional speech aired on television.

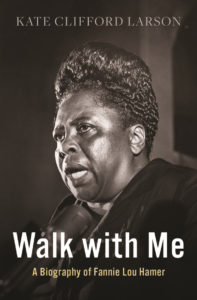

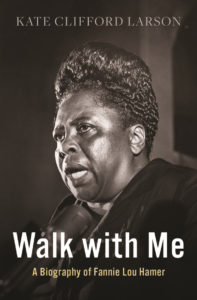

Historian Kate Clifford Larson has written a new book, “Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer,” that reveals details of the faith and life of Hamer, who was born 104 years ago Wednesday (Oct. 6) and died in 1977.

“Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer” by Kate Clifford Larson. Courtesy image

Inspired by young Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers who preached Bible passages about liberation at her church in Ruleville, Mississippi, in 1962, Hamer became a singer and speaker for equal rights and human rights.

“She crawled her way through extraordinarily difficult circumstances to bring her voice to the nation to be heard,” Larson told Religion News Service. “And she knew that she was representing so many people that were not heard.”

Larson spoke to RNS about Hamer’s faith, her favorite spirituals and how music helped the activist and advocate survive.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a biography of Fannie Lou Hamer and how would you describe her as a woman of faith?

I published a book about (Harriet) Tubman and Hamer is so similar to Harriet Tubman, only 100 years later. I decided to start looking into her life and thinking I should do a biography of Hamer. I just became hooked. There were so many similarities, and things I could see in Hamer that I just thought, we need to have a refresher about Fannie Lou Hamer and the strength of her character and how she survived such incredible adversity and found the same kind of solace that Harriet Tubman did — in her faith, in her family and the community — to keep going and fighting and to try to make the world a better place.

It seems she is relatively unknown in many circles despite the credit she’s given by civil rights veterans for her work.

It is curious that she is not well known broadly. And I hope that changes, because I think we need to look back sometimes to see how far we’ve come. And with Hamer, the things that happened to her — she faced the world by confronting that trauma, and that violence, without hate. And the only way she could do that was through her faith, and talking to God and saying: Where are you, what is happening here, give me the strength to carry this weight and to move forward. And she did. She knew hate could really destroy her — that feeling of hating the people that were trying to kill her and subjugate her. She managed to rise above it because she had a greater mission in front of her.

Why did you title the book “Walk With Me”?

The title is from the song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Mississippi, jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her. She asked Euvester to please sing with her because she needed to find strength and she needed God to be with her. So she sang that song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She needed to feel there was something bigger that would help her survive those moments where it wasn’t so clear she would survive. And I found it so powerful that she would do that. She survived that night and was able to get up and walk the next morning.

What other spirituals and gospel songs were particularly important to Hamer as she fought for voting rights and other social justice causes?

One of her favorites is “This Little Light of Mine.” She sang that everywhere, all the time. It’s kind of her anthem. There were some other spirituals, but really, most of the ones she sang a lot during the movement were those crossover folk songs, rooted in Christian spirituals, like “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” She grew up not only in a very strong church environment, the Baptist church, but she grew up in the fields of Mississippi where there were work songs in the fields, call and response songs. Where she grew up was actually the birthplace of the Delta blues music.

She also quoted the Bible to the people she differed with. Were there particular biblical lessons Hamer applied to her fight to help her fellow Black Mississippians?

She used the Bible in many different ways. She used it to shame her white oppressors who claimed also to be Christians, following the path of Christ. She would use the Bible and say: Are you following this path by what you’re doing to me, to my fellow community members and family members? And she used the Bible passages to remind Christian ministers: This is your job, and what are you doing up on that pulpit? You’re telling people to be patient. Well, in the Bible it says stand up and lead people out of Egypt.

You wrote about William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, Hamer’s congregation, throughout the book. What happened there, over the years as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups used it as a place for meetings, classes and rallies?

The church, the ministers participated in the movement and had meetings in that church at great risk to themselves and to the church, and in fact, the church was bombed a couple of times even though the fires were put out, fortunately, very quickly. There were residents in the community that took their lives and put them on the line. They were at great risk, to go to those meetings, to conduct those meetings, to go out and do voter registration drives. It was all centered on the church community because that was really the only community buildings in many of these places where people could meet together to have these discussions.

You said Hamer was at a crossroads as she first listened to those SNCC (pronounced “snick”) activists seeking more people to join their cause.

She experienced trauma, and she had been sterilized against her will — she didn’t give permission — and she had gone through this very deep depression, and it tested her faith. It tested her understanding of the world, and she came out of that and went to this meeting in Ruleville in 1962 and when she heard those young people and their passion and their willingness to put their lives on the line for her, she viewed them as the “New Kingdom.” So it was more than a crossroads for her. It was a moment where she could see the future in these young people, and she called them the “New Kingdom (right here) on earth.” If they were willing to stand up and risk their lives then she could, at 45, 46 years old, stand up herself. That was a crossroads. She made that choice to stand up, publicly, and move forward.

Briefly, the story goes like this: a man has three people that work for him. (We can call them servants or employees.) He leaves them five talents, two talents, and one talent, respectively, while he travels to another country. (A talent could be interpreted as a way of making money or money itself. For this, let’s just say a talent is worth $10,000.) When he comes back after a long time, the first employee now has ten talents ($100,000), the second has four talents ($40,000), and the last one gives his talent ($10,000) back to his employer. The employer rewards the two servants that made him money, but calls the other one wicked and “cast[s] the unprofitable servant into outer darkness” where it says there’ll be “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (

Briefly, the story goes like this: a man has three people that work for him. (We can call them servants or employees.) He leaves them five talents, two talents, and one talent, respectively, while he travels to another country. (A talent could be interpreted as a way of making money or money itself. For this, let’s just say a talent is worth $10,000.) When he comes back after a long time, the first employee now has ten talents ($100,000), the second has four talents ($40,000), and the last one gives his talent ($10,000) back to his employer. The employer rewards the two servants that made him money, but calls the other one wicked and “cast[s] the unprofitable servant into outer darkness” where it says there’ll be “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (