The forgotten story of Black soldiers and the Red Ball Express during World War II

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower had a problem. In June 1944, Allied forces had landed on Normandy Beach in France and were moving east toward Nazi Germany at a clip of sometimes 75 miles (121 kilometers) per day.

With most of the French rail system in ruins, the Allies had to find a way to transport supplies to the advancing soldiers.

“Our spearheads … were moving swiftly,” Eisenhower later recalled. “The supply service had to catch these with loaded trucks. Every mile doubled the difficulty because the supply truck had always to make a two-way run to the beaches and back, in order to deliver another load to the marching troops.”

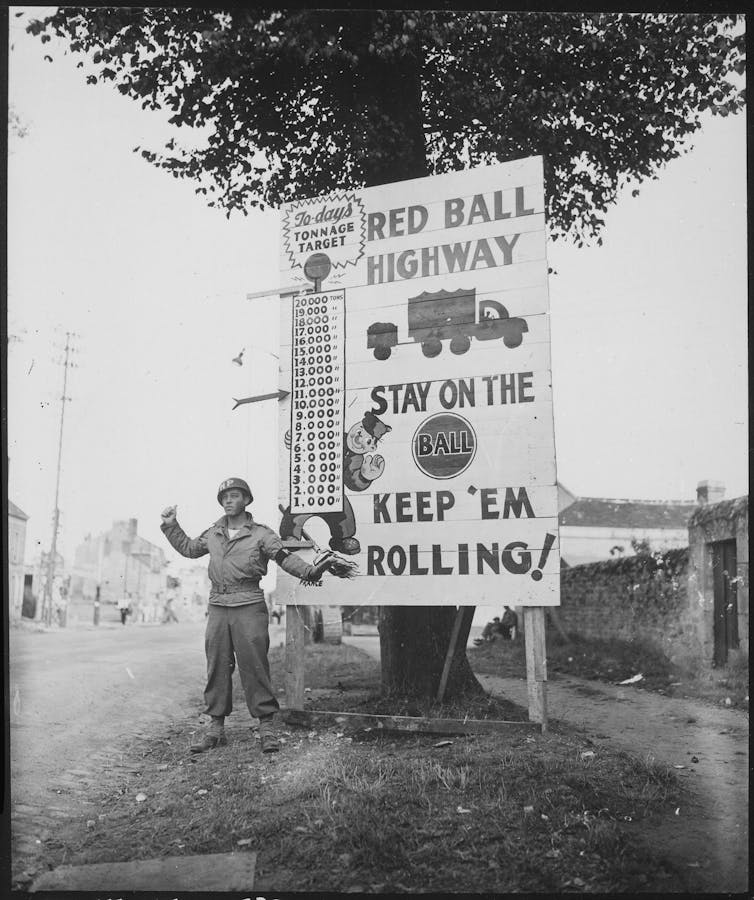

The solution to this logistics problem was the creation of the Red Ball Express, a massive fleet of nearly 6,000 2½-ton General Motors cargo trucks. The term Red Ball came from a railway tradition whereby railmen marked priority cars with a red dot.

From August through November 1944, 23,000 American truck drivers and cargo loaders – 70% of whom were Black – moved more than 400,000 tons of ammunition, gasoline, medical supplies and rations to battlefronts in France, Belgium and Germany.

These Red Ball Express trucks and the Black men who drove and loaded them made the U.S. Army the most mobile and mechanized force in the war.

They also demonstrated what military planners have long understood – logistics shape what is possible on the fields of battle.

That’s a point well known in today’s war in Ukraine: As the Russian invasion stretches into its second month, logistics have been an important factor.

Supplying the front lines

The Red Ball Express gave the Allies a strategic advantage over the German infantry divisions, which were overly reliant on rail, wagon trains and horses to move troops and supplies.

A typical German division during the same period had nearly 10 times as many horses as motor vehicles and ran on oats just as much as oil. This limited the range of the vaunted Blitzkrieg, or lightning attacks, because German tanks and motorized units could not move far ahead of their infantry divisions and supplies.

Driving day and night, the Red Ball truckers earned a reputation as tireless and fearless troops. They steered their loud, rough-driving trucks down pitch-black country roads and through narrow lanes in French towns. They drove fast and adopted the French phrase “tout de suite” – immediately, right now – as their motto.

Gen. George C. Patton “wanted us to eat, sleep, and drive, but mostly drive,” one trucker recalled.

James Rookard, a 19-year-old truck driver from Maple Heights, Ohio, saw trucks get blown up and feared for his life.

“There were dead bodies and dead horses on the highways after bombs dropped,” he said. “I was scared, but I did my job, hoping for the best. Being young and about 4,000 miles away from home, anybody would be scared.”

Patton concluded that “the 2½ truck is our most valuable weapon,” and Col. John D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander’s son, argued that without the Red Ball truck drivers, “the advance across France could not have been made.”

Fighting Nazis and racism

The Red Ball Express was a microcosm of the larger Black American experience during World War II. Prompted by the Pittsburgh Courier, an influential Black newspaper at the time, Black Americans rallied behind the Double V campaign during the war, which aimed to secure victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home.

Many soldiers saw their service as a way to demonstrate the capabilities of their race.

The Army assigned Black troops almost exclusively to service and supply roles, because military leaders believed they lacked the intelligence, courage and skill needed to fight in combat units.

Despite the racism they encountered during training and deployment, Black troops served bravely in every theater of World War II. Many saw patriotism and a willingness to fight as two characteristics by which manhood and citizenship were defined.

The boundaries between combat roles and service roles also blurred in war zones. Black truck drivers often had to fight their way through enemy pockets and sometimes required armored escorts to get valuable cargo to the front.

Many of the white American soldiers who relied on supplies delivered by the Red Ball Express recognized the drivers’ valor at the time.

[There’s plenty of opinion out there. We supply facts and analysis, based in research. Get The Conversation’s Politics Weekly.]

An armored division commander credited the Red Ball drivers with allowing tankers to refuel and rearm while fighting. The Black drivers “delivered gas under constant fire,” he said. “Damned if I’d want their job. They have what it takes.”

A 5th Armored Division tank driver said, “If it wasn’t for the Red Ball we couldn’t have moved. They all were Black drivers and they delivered in the heat of combat. We’d be in our tanks praying for them to come up.”

Logistics in Ukraine

Days into the war, Ukraine’s armed forces destroyed all railway links between Ukraine and Russia to thwart the transport of Russian military equipment and tanks.

Relying on trucks and road networks, Russian convoys encountered fuel shortages and counterattacks from Ukrainian military and civilians.

The Russian military’s ability to move supplies across extended distances – as well as Ukraine’s ability to disrupt those supply lines – is pivotal in determining the future direction of the war.![]()

Matthew Delmont, Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Professor of History, Dartmouth College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.