by Emily McFarlan Miller, RNS | Nov 3, 2022 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Heritage, Social Justice |

WHEATON, Ill. (RNS) — The Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr. still remembers clearly the moment as a teenager he thought he was going to die.

Parker was 16 years old, visiting family in Mississippi, when he woke in the early morning hours to the sound of voices in the house. Moments later, the door to his bedroom opened and a man pointed a flashlight and a pistol in his face.

He shut his eyes tight, but the shot never came.

The man moved on to the next bedroom and the next before finding and kidnapping his cousin — Emmett Till.

It was the last time he saw his best friend alive, Parker, now in his 80s, told a packed concert hall Tuesday night (Oct. 25) at Wheaton College, the evangelical flagship school in the Chicago suburbs.

What happened next — Till’s brutal murder, his mother’s decision to allow an open casket at the 14-year-old victim’s funeral, so the country could see what had been done to her son — shone a light on racial violence in the United States and became a catalyst for the civil rights movement.

Mamie Till-Mobley weeps at her son’s funeral on Sept. 6, 1955, in Chicago. (Chicago Sun-Times/AP Photo)

“A picture’s worth a thousand words. That picture made a statement. It went throughout the world, all over the world, and it still speaks,” Parker said of the photographs of Till in his casket, taken by David Jackson and first published in Jet magazine.

The story of Till continues to resonate because it “provides us with a lens to understand racial conflict in our own moment,” said Theon Hill, associate professor of communications at Wheaton College and primary organizer and moderator of Tuesday’s event, “Remembering Emmett Till: A Conversation on Race, Nation and Faith.”

“When we see George Floyd killed right in front of us due to the officer’s knee,” said Hill, “when we see Breonna Taylor’s death, when we see Ahmaud Arbery, we’re trying to make sense of what’s happening, and Till’s death, as tragic as it will always be, provides us with a grammar to understand this is what’s happening and this is how you might respond in your moment.”

The enduring relevance of Till’s death is apparent in the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, making lynching a federal hate crime and signed in March by President Joe Biden, nearly 70 years after Till’s murder.

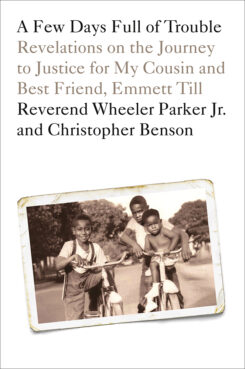

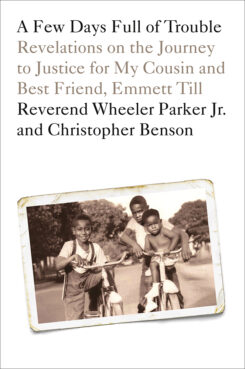

“A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on the Journey to Justice for My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett Till” by the Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr. and Christopher Benson. Courtesy image

It’s also borne out in the critical acclaim for a new film, “Till,” centering on Till’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, and her fight for justice for her son, which appears in theaters nationwide this week. In January, Parker will publish his recollections of his cousin, “A Few Days Full of Trouble: Revelations on the Journey to Justice for My Cousin and Best Friend, Emmett Till.”

It was 30 years before anybody asked Parker his account of what had happened over the handful of days in 1955 he and his cousin, who lived in Chicago, spent in Mississippi visiting family, according to Parker, the last surviving witness to Till’s abduction.

In Parker’s account, Till is a jokester, the boy next door he accompanied fishing, picnicking and on other trips. When his cousin found out he was planning to take the train down South to visit his grandfather, he insisted on going too.

“If you didn’t live in Mississippi at that time or experience what it was like, you have no idea what it was like,” Parker said.

He had lived in the South until he was 7 and knew “what you had to do to stay alive and what could happen to you,” he said.

Till didn’t.

When the younger boy whistled in the presence of a white woman outside a store, Parker said, the cousins left in a hurry. He worried what could happen in a place and time when a Black man couldn’t so much as look at a white woman, he said.

But days passed, and they’d nearly forgotten about the incident. Then came the moment Parker heard voices in his grandfather’s home at about 2:30 a.m. on a Sunday morning, asking about the boys from Chicago.

“Sunday morning should be the safest place on earth for a young man in his house — on Sunday morning, waiting to go to church,” he said.

Shaking and sure he was about to die, he prayed, “God, if you just let me live, I’m going to get my life together.”

That Monday, he returned to Chicago alone, his life changed “completely,” said Parker, now pastor and district superintendent of the Argo Temple Church of God in Christ in Summit, Illinois.

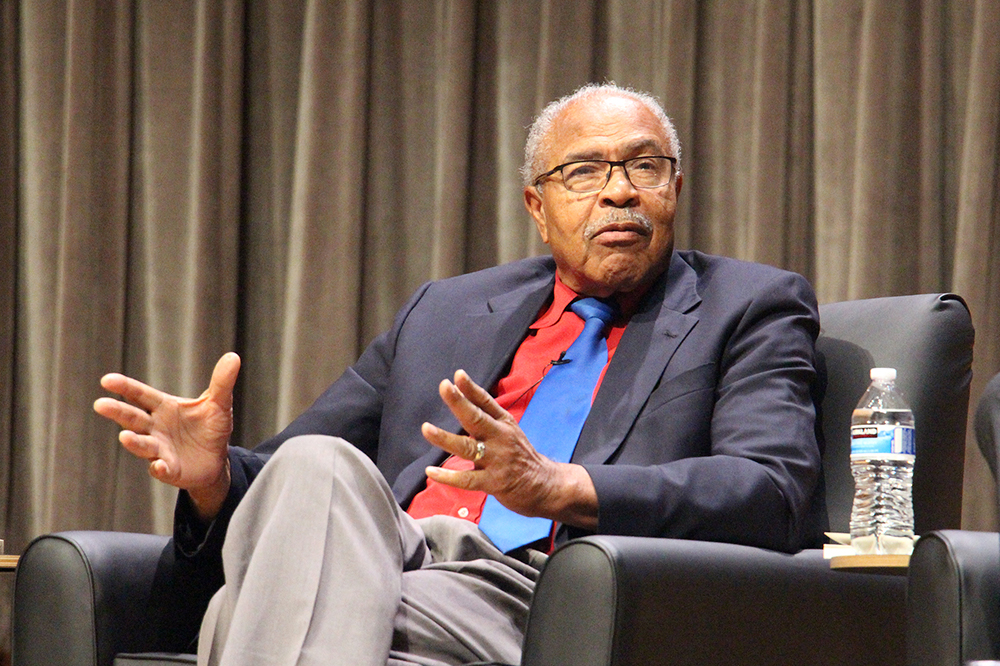

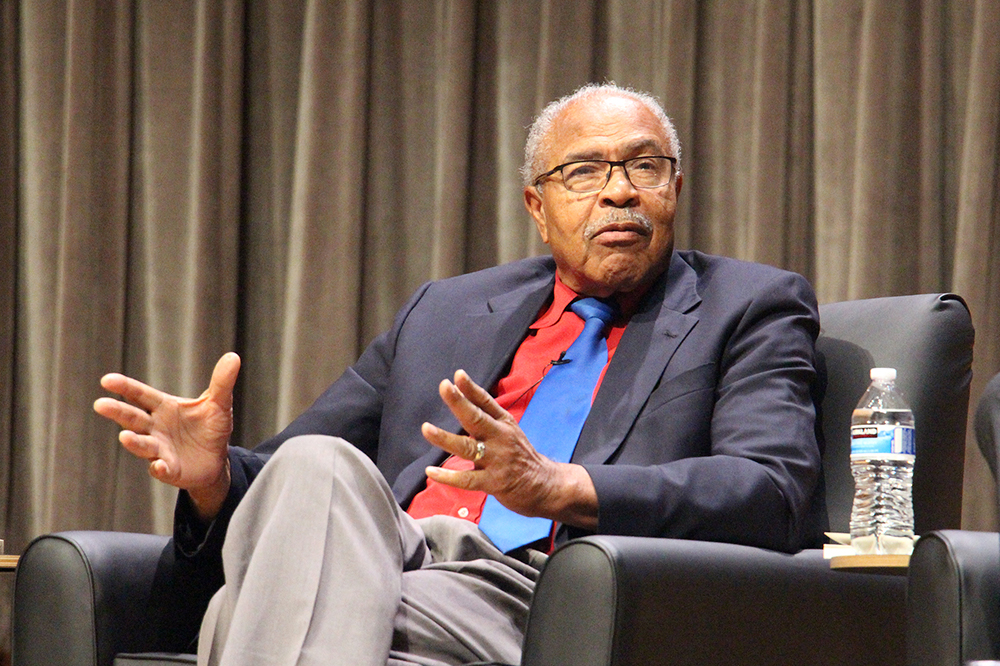

The Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr. speaks during the “Remembering Emmett Till: A Conversation on Race, Nation and Faith” event at Wheaton College, Oct. 25, 2022, in Wheaton, Illinois. RNS photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

What happened to Till changed the country, too.

Dave Tell, author of the 2019 book “Remembering Emmett Till,” told the audience Tuesday night that he had become invested in civil rights because of Till’s story.

“The Till story prompted a new generation to stand up for justice, and I think the good news of the night is that the Till story — Rev. Parker’s story — is still motivating a new generation,” Tell said.

It’s a story, he said, the U.S. needs to hear today more than ever. Considering the stories of Floyd and others against the backdrop of Till’s murder, it’s hard to minimize their killings as “a problem of a bad apple or bad cop,” he said.

And the church has a role to play in sharing that story, both Tell and Parker agreed.

The biblical Book of Genesis tells the story of Abel, murdered by his brother Cain, Tell pointed out. In the story, God says Abel’s blood cries out to him from the ground, where Cain has tried to bury what he did.

If God demands that voices that have been buried be brought to light as part of the work of justice and healing, shouldn’t the church? Tell asked.

“We’ve got to keep the legacy going — got to keep the story going — and not with animosity,” Parker added.

“Just tell the story. It’s history. It’s real. Tell what happened,” he said.

by Emily McFarlan Miller, RNS | Oct 11, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News |

Wheaton College has an open library commemorating Tolkien and the “Lord of the Rings” universe, formally known as the Marion E. Wade Center, at the college in Wheaton, Illinois. RNS Photo by Emily Miller

WHEATON, Illinois (RNS) — It started with an inkling.

It was the 1950s. Clyde S. Kilby, then an English professor at Wheaton College, had a feeling about a British author he’d been reading named C.S. Lewis — that he was “probably going to be famous one day,” according to Crystal Downing, co-director of Wheaton’s Marion E. Wade Center.

So Kilby wrote to Lewis and started collecting books and letters written by the author. He met some of Lewis’ friends and family.

Years later, he was traveling to England to work with Lewis’ Oxford University colleague J.R.R. Tolkien on “The Silmarillion,” a collection of stories that fill in the background of Tolkien’s beloved “Lord of the Rings” trilogy.

Decades later, the professor’s collection of letters and books has grown to become the Marion E. Wade Center, one of the foremost research centers not only on Lewis, but also Tolkien and five other British Christian authors who had influenced Lewis’ work.

Now the Wade Center is preparing for an influx of archival materials and interest as Tolkien and his fantasy world of Middle-earth have once again grabbed the spotlight.

RELATED: Tolkien fans hope to turn his house into a ‘Rivendell’ for writers and filmmakers

After years of speculation, the first two episodes of “The Rings of Power” — the multimillion dollar prequel series produced by Amazon Studios and inspired by the appendices to Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” novels, debuted Thursday night (Sept. 1) on Prime Video, Amazon’s streaming service.

“Tolkien probably would never have gotten published if it weren’t for Lewis,’” Downing said.

“And, of course, Lewis wouldn’t be famous if it weren’t for Tolkien because Tolkien is the one who convinced him he could be a Christian.”

The Wade Center can feel like the evangelical Christian college’s best-kept secret, housed in a cozy building that looks like a stone English cottage nestled into Wheaton’s suburban Chicago campus.

Laura Schmidt, archivist and Tolkien specialist at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College. RNS Photo by Emily Miller

But Laura Schmidt, archivist and Tolkien specialist at the center, said, “Tolkien knew about Wheaton College. He knew about the Wade Center.”

Pre-pandemic, the Wade Center welcomed about 10,000 people a year, ranging from elementary students from Chicago-area school districts to scholars from around the world.

Its archive includes books belonging to authors Lewis, Tolkien, Dorothy Sayers, George MacDonald, G.K. Chesterton, Owen Barfield and Charles Williams (including more than 2,400 from Lewis’ personal library alone). It also includes original manuscripts of their work, letters they wrote and oral history recordings of people who knew them.

Among its treasures are rare, autographed first editions of Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings” trilogy and “The Hobbit,” all featuring cover artwork designed by the author himself.

Marion E Wade Center, home to the Tolkien Library, is housed on the campus of Wheaton College in Illinois. RNS Photo by Emily Miller

An exhibit in the museum shows how those covers have changed over time, from Tolkien’s artful eye of Sauron circled by Elvish script to a 1980s paperback featuring an Olan Mills-style portrait of the dwarf Gimli and elf Legolas with flowing, romance-novel hair.

Another exhibit atop the dining room table from Lewis’ house displays merchandise that accompanied the popular “Lord of the Rings” films released in the early 2000’s and more recent films based on “The Hobbit.” There is a Lego scene of The Shire; a letter opener made to look like Bilbo Baggins’ Elven sword, Sting; even a board game.

The museum also features the small, nearly hobbit-sized desk at which Tolkien wrote “The Hobbit” and much of “Lord of the Rings,” as well as the dip pen he used to write, slightly melted on the end he used to tamp his pipe tobacco. Its most popular attraction, though, is the wardrobe carved by Lewis’ grandfather that inspired his beloved children’s story “The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.”

Yes, there are fur coats inside.

On Tuesday, scholars from Ireland and Australia perused texts in the reading room, home to at least one copy of every book published by the seven Wade authors, as well as nearly everything ever published about them.

Meanwhile, across campus, members of the Wheaton College Tolkien Society shared their plans for watching “The Rings of Power” while manning a table at Wheaton’s club and ministry fair. The series had yet to premiere, and members were feeling both excited and apprehensive.

Elizabeth Church, president of the Wheaton College Tolkien Society, was one of several students helping to run a booth about the club at the school’s Club and Ministry Fair. RNS Photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

Tolkien Society President Elizabeth Church said that what drew her to Tolkien’s stories was the “found family aspect.” In the “Lord of the Rings” series, the Fellowship of the Ring brings together hobbits, elves, dwarves, humans and others for a single purpose: to destroy the one ring and defeat evil.

Church has found a similar family in Wheaton’s Tolkien Society, she said.

“We’re very much like the fellowship in the books in that we are a ragtag bunch of people who come together for one goal, which is to be a fellowship,” the senior said.

The first two episodes of “The Rings of Power” set up an epic battle between good and evil. In one of its opening scenes, a young Galadriel, who will become the elven Lady of Lórien in “Lord of the Rings,” questions how to recognize the light when evil masquerades as good.

The answer comes near the end of the episode: “Sometimes we cannot know until we have touched the darkness.”

Light and dark, good and evil are themes found throughout Tolkien’s work, Schmidt said before watching the new series.

And Schmidt, who advises the Tolkien Society, expects the series to get dark.

The Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College includes a wide variety of memorabilia including cards, miniature swords and other decorations symbolic of “The Hobbit” and “The Lord of the Rings” series. RNS Photo by Emily McFarlan Miller

It’s drawn from writings set before the events of “Lord of the Rings,” when the evil sorcerer Sauron is handing out what Schmidt jokingly called “friendship rings” to men, dwarves and elves that he’ll later use to control Middle-earth. It’s a long time before the conclusion of “The Return of the King,” the final book in Tolkien’s series, when good ultimately triumphs over evil.

Those themes are also part of the reason why the author’s work not only endures nearly 70 years after it first was published, but also has inspired what has been called the most expensive TV show ever made.

“I think that’s going to really resonate with people in this time and era now, because there’s a lot of darkness that we’re trying to figure out. That’s why these books are pertinent to our time, and it’s going to, hopefully, inspire hope in people’s hearts that the fight is worth fighting,” Schmidt said.

“Maybe we’ll get a ‘Return of the King’ in a few years.”

by Christine A. Scheller | Nov 25, 2018 | Headline News |

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.

As vice president of the Multiethnic Student Association at Taylor, Canada successfully petitioned the school to restructure its ethnic recruiter position and to re-establish its director of multiethnic student services position. He was also an original member of Taylor Black Men, a student group that provided support for young men who didn’t necessarily feel comfortable discussing the unique challenges they faced with White classmates.

“I was really excited that I was able to do that, but there’s also this sadness that I have now because, although I felt like it was important, it painted a lot of my senior year,” said Canada, who occasionally writes for UrbanFaith.

He was compelled to act, he said, because he feared that no one else would if he didn’t. “I was blessed enough that I had a lot of coping skills,” he explained. “I could ‘code switch,’ and sometimes get in that middle world, where I could deal with both cultures, but there were several students who couldn’t.”

It is those students that concern a number of professionals who work at Christian colleges around the nation, and especially those affiliated with the Council of Christian Colleges and Universities. The CCCU, an international association of Christian institutions of higher education, seeks to provide resources and support for the students, faculty, and administrations of its member schools. Assisting students of color with their often difficult transition into the culture of predominately White Christian campuses has become one of its chief missions during its 36 years of existence.

Slow but Steady Progress

Twelve years ago the CCCU established a Racial Harmony Award to celebrate the achievements of its member institutions in the areas of “diversity, racial harmony, and reconciliation.”

In 2001, the organization’s board affirmed its commitment. “If we do not bring the issues of racial-ethnic reconciliation and multi-ethnicity into the mainstream of Christian higher education, our campuses will always stay on the outside fringes,” remarked Sam Barkat, former board member and provost of Nyack College in Nyack, New York.

CCCU schools have made “steady gains” since then, according to a report co-authored by Robert Reyes, research director at Goshen College’s Center for Intercultural Teaching and Learning and a member of CCCU’s Commission for Advancing Intercultural Competencies.

Robert Reyes: “We’re supposed to be unified as Christians.”

Reyes and his colleagues found that overall percentage of students of color increased from 16.6 percent to 19.9 percent at CCCU schools between 2003 and 2009 and graduation rates for these students also increased, from 14.8 percent to 17 percent, which still only adds up to a tiny fraction of all students at CCCU’s 115 North American affiliate schools.

According to Reyes, CCCU has a new research director and is developing a proactive research agenda related to these issues. This kind of research “creates a certain level of anxiety,” he said, because it categorizes people and theoretically separates us when we’re supposed to be unified as Christians. “I think it’s a misunderstanding of what the unity of the body is, and what unity means in the Christian faith,” said Reyes.

For those, like Reyes and Canada, who are engaged in diversity work on CCCU campuses, the task can feel like slogging through a murky swamp. UrbanFaith talked to current and former diversity workers at nine CCCU schools about their efforts and experiences. We repeatedly heard that students of color face unique challenges on these campuses and that CCCU schools are not always prepared, or willing, to deal with them. We also heard about successes and how challenging they can be.

The Problem — a Whole Different God

Multiple sources said students of color at Christian colleges are routinely harassed with racially insensitive jokes and comments by members of their campus communities, for example, and that this harassment is sometimes not taken seriously enough by school administrators.

When racism isn’t overt, students often feel like they won’t be accepted by their school communities unless they suppress their ethnic identities. Many students feel profoundly lonely on majority-White CCCU campuses, our sources said.

Dante Upshaw, for example, has been both a student and a staff member at evangelical schools. He recalled the challenge that worship presented when he was a student at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago.

“For the average White student, it’s an easy crossover. … It’s kind of this big youth group. But for the Black student, the Hispanic student, this is a whole different God,” said Upshaw.

He was unfamiliar with the songs that were sung in chapel, for example, and found himself in conversations about what constitutes godly worship. “I was a young person having to articulate and defend. That’s a lot of pressure for a freshman,” said Upshaw.

Monica Smith: “We haven’t gone far enough.”

Monica Smith has seen the same phenomenon played out on her school’s campus. As assistant to the provost for multicultural concerns at Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania, she said students of color once complained to her about being judged for skipping chapel services that felt culturally foreign to them. They were told they should be able to worship no matter what kind of music or speaker was up front. “The retort was, ‘You’re right, so why can’t it sound like what I’m used to?’” said Smith, who also teaches courses in social work.

Smith and her colleagues have identified four specific areas of challenge that confront students of color at Eastern: financial, academic, social, and spiritual. “If students are struggling in those areas, they really can’t pay attention in the classroom,” said Smith.

The university is making headway, but it’s slow, she said. “As much as we have done administratively and in the academic arena, I still don’t know that our university’s administration has gone far enough with this.”

Institutional Challenges — Like Turning the Titanic

Upshaw served as a minority recruiting officer and assistant director of the office of multi-cultural development at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, in the early 2000s. He said the number of non-White students who were in pain over their experience at the school would have been as big as his admissions file.

He recalled leaving school one day to commute home to Chicago when he saw a student of color sitting on the stairs “like a lonely puppy.” Upshaw read the student’s demeanor as saying, “You about to leave me here, man? You’re actually going to leave and go to your home?”

Dante Upshaw: “Too many students felt alone.”

“There were just too many students like that, where they felt so alone on this beautiful, immaculate campus with great food service and great athletics,” Upshaw said. “Those were some hard years.”

In response to the need he saw, Upshaw founded Global Urban Perspectives, a multiethnic student group devoted to urban issues. He believes it was successful in part because it helped foster healthy relationships.

“The fact that we were together in a safe setting where we were given space to be ourselves, I think that really struck a chord with many of the students,” he said.

“It’s a wealthy system, it’s an established system, it’s a strong historic system, and it’s a very Christian religious system,” said Upshaw of the institutional challenges he faced at Wheaton. “Changing a system like that would be akin to turning the Titanic … It is going to take a long time, and it’s going to be real slow.”

Even so, Upshaw said he saw “the ship” turn quickly when influential individuals decided to act. Too often, though, he saw inaction born of the fear of alienating potential donors. Upshaw left the school, in part, because he was frustrated with the administration’s commitment to a broadly applied quota system that he felt undermined his efforts to recruit more students of color.

Additive and Subtractive Approaches

Although Joshua Canada is ambivalent about his experience at Taylor University, he returned there for graduate school and now serves as an adviser to the Black Student Union at Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California, where he is also a residence director. He said not all students of color struggle with the racial dynamics on their campuses and some students rarely do.

“In their ethnic development, they’re not dealing with this tension, or this is what they’ve done their whole life and they know how to do this,” said Canada.

Joshua Canada: “To be successful, our vision of being multicultural must be transformative.”

He described two approaches to multiculturalism, one that is additive and one that is subtractive. With the additive approach, elements of non-European culture are added to the core culture, he said, and with the subtractive approach, people of color drop elements of their culture to assimilate into the majority culture.

“Students feel it, if it’s additive,” Canada said. “We did Black History Month. We did Martin Luther King Jr. Day. It’s a nice gesture, but people realize it isn’t who we are.”

“To really be successful, we have to come to a place where our vision of being multicultural is more transformative and then it really does change aspects of the institution. It really does change the big-picture experience, and not in a way that is unfaithful to the history of the institution, but that maybe acknowledges gaps.”

George Yancey is a University of North Texas sociologist and the author of numerous books, including Neither Jew nor Greek: Exploring Issues of Racial Diversity on Protestant College Campuses. (Canada’s UrbanFaith interview with Yancey prompted us to investigate the issue further.) According to Yancey, the task of student retention at Christian colleges is complicated by the evangelical community’s habitual conflation of faith and culture.

“There’s an issue in retaining students of color in higher education in general,” he told UrbanFaith, “but I think Christian College campuses have even more of a challenge because of some of the dynamics that are there. A lot of times, the way the faith is practiced is racialized. People don’t always realize it.”

Nurturing Dialogue

It wasn’t only African Americans, however, who recounted stories about the challenges students of color face at CCCU institutions. Jon Purple is dean for student life programs at Cedarville University in Cedarville, Ohio. He recalls the mother of an incoming student crying when she dropped her young Black son off at the rural Ohio campus, and not just because he was leaving home.

“She was in tears and was afraid to leave her son here, because of very real fears that some good-ol’ White boys might accost her son,” said Purple.

Continued on Page 2.

by Christine A. Scheller | Apr 27, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

Nyack College students say the number one benefit of attending Nyack is the preparation they receive to work in diverse environments. (Photo courtesy of Nyack College.)

In the years since Nyack College in Nyack, New York, shared the 2001 Council for Christian Colleges & Universities Racial Harmony Award with another college, the school has become so thoroughly immersed in racial and ethnic integration that it no longer applies to be considered for the honor, its president Michael Scales and provost David Turk told UrbanFaith on a recent visit to the campus.

“We used to submit the stuff all the time, but we decided we would just stop because our communication is on a different level. They’re talking about certain things they’re doing; we’re talking about a whole different culture,” said Turk.

“If you look back over all those awards—I was even chair for a little while—they’re giving awards for prescriptions,” said Scales.

For Nyack, “intentional diversity” is one of the school’s five core values.

“We think all these are what [founder] A.B. Simpson taught back when we first started this. So, we tried to get back to what is in our own DNA,” said Scales.

At its main campus, Nyack is 37 percent White, 24 percent Black, 14-15 percent Asian, and the rest mixed-race and other ethnicities, Scales said. At its satellite campus in Manhattan, the student body is 46 percent Black, 11 percent Asian, 28 percent Latino, and 6 percent White. There is also a high level of age and denominational diversity, Scales said, with many adult learners attending the city campus.

Diversity Mavericks: Nyack President Michael Scales and Provost David Turk. (Photo courtesy of Explorations Media L.L.C.)

The push toward integration was intentional, said Turk, who has been teaching at Nyack

since 1978. During the 1980s and 90s, the school went through “rough periods” and had difficulty retaining faculty, he said. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise when the decision was made to innovate in the late 1990s.

“We then had the luxury to develop some things in an entrepreneurial way that other schools with an entrenched faculty group just did not have. One of those ways was diversifying,” said Turk.

Scales described Nyack’s efforts as a “noble experiment,” but said it is one that hasn’t been without costs. The average building on Nyack’s main campus is 76 years old, he said, and the school has had trouble attracting “monied” White investors to update facilities.

“I think it’s changing,” said Scales. “For the first time, we have some people coming around the table who really can be transformative agents.”

Alumni are divided, said Turk. “Some will say this is the best and the greatest thing, and some will just be blunt and say, ‘Well David, I’m not going to send my daughter to your school. She might date a Black guy.’”

In surveys, students say the number one benefit of attending Nyack is the preparation they receive to work in diverse environments, Turk said.

“The truth is that the people who are going to be leading this country are the students who come to places like this,” said Scales.

Creating Sustainable Change

In order to create sustainable change, faith-based institutions must link to their history, their mission, and to biblical principles, George Fox University’s dean of transitions and inclusion Joel Perez told UrbanFaith when he was interviewed for our previous article about the challenges students of color face at Christian colleges. (Perez researched diversity at CCCU campuses for his doctoral dissertation.)

Joel Perez: 'Sustainable change must be linked to history, mission, and biblical principles.'

“Once you anchor [diversity] in those things, then it’s harder for an institution, when it does change leadership, for someone new to come in and say it’s not going to be a focus or we’re not going to talk about it anymore,” said Perez. “If schools don’t do that initially, or don’t go back and make those connections, I think it’s easier for a school to sort of lose its way in doing the work.”

Unintentional Diversity

UrbanFaith asked Turk if Nyack’s proximity to New York City gives it an advantage in attracting more faculty of color who may be reluctant to move to the rural settings where many Christian colleges are located. He rejects the common argument that geography is a deterrent to pursuing diversity, saying faculty of color want to serve and would be willing to go to rural campuses. His work with Nyack’s Manhattan campus taught him that finding qualified people is as easy as reaching out to their church networks. Now when peers tell him they can’t find non-white faculty, he asks if they’ve even tried those networks.

“I just don’t buy the argument,” said Turk.

James Steen: 'HBU's multi-racial campus is refreshing.'

At Houston Baptist University in Houston, Texas, where the student body is only one-third White, diversity is unintentional, said James Steen, its vice president of enrollment management. Instead it simply reflects the southwest Houston demographic. Forty percent of the student body lives within a 10 mile radius of the campus, he said.

“We’re not striving or working to try to attract more diversity. It’s just who we are and it’s just part of the culture. So, it’s a refreshing thing to be a part of,” said Steen, who previously worked at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, where, he says, the student body is 70 percent White.

Twenty-eight percent of Houston Baptist’s student body is Hispanic, 29 percent is White, 19 percent is African American, 14 percent is Asian, and 6 percent is multi-racial, Steen said. The faculty, however, is mostly White, but more diverse than Baylor’s.

Because Houston Baptist has had a highly diverse student body for so long, the school has “grown comfortable” with its diversity, director of student life Whittington C. Goodwin said.

“Now we’re going towards really giving each student a way that they can develop academically, socially and spiritually,” said Goodwin, who came to Houston Baptist 18 months ago from predominantly White Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama.

Houston Baptist’s diversity not only reflects community demographics, it also reflects the city’s churches, Goodwin said, many of which are “making huge pushes to really integrate those worship services, so it’s not the most segregated hour in America anymore.”

Whit Goodwin: 'Differences make for good spiritual formation opportunities.'

It can be a challenge to clearly define “who your students are” on such a racially integrated campus, said Steen. “What may appeal to one student group is not going to appeal to another student group.” For example one group may prefer a country western dance while another would opt for a hip hop concert.

“We’re cognizant of differences here, but we’re also cognizant of human nature, of what God has called us to be, and all of us living, working, studying, worshiping together makes for a really wonderful educational opportunity, but also a wonderful spiritual formation opportunity,” said Goodwin.

Waiting for the Immigration Law to Catch Up

At Lipscomb University in Nashville, Tennessee, the student body is only about 16 percent non-white, its president Randolph Lowry told UrbanFaith, but at one point last year it was the most ethnically diverse campus — religious or secular — in the state of Tennessee.

“The world is a pretty global, cross cultural place. The degree to which the school can reflect that cross-cultural nature, it’s going to be much easier for our students then to go into the world and feel comfortable and be effective,” said Lowry.

Randolph Lowry: 'Educating undocumented immigrants is a calling.'

In addition to a school-wide service requirement that places students in cross-cultural off-campus environments, Lipscomb sponsors Conversations of Significance that bring together ethnic groups for cross-cultural dialogue and the Davidson Group, which pairs community members of different ethnicities for year-long relationship building, Lowry said. The school also admits and financially supports undocumented immigrants.

“We’d like the federal [government] to be more courageous about immigration policy, but until they do that, I think we have to look at what we feel called to do as the Christian community,” said Lowry. “Our board has recognized that Jesus continually responded to those in the world who really were the outcasts. … Some of our students of color fall in that category, and we want to do what we can to respond to their needs.”

Pursuing First-Generation Students

Interracial dialogue is a priority at Lipscomb University. (Photo courtesy of Lipscomb University.)

All the highly diverse schools UrbanFaith talked to have a significant number of first-generation students on their campuses — that is, students who are the first in their families to pursue higher education.

North Park University in Chicago, Illinois, for example, recruits first-generation students as part of its mission, regardless of their race or ethnicity, dean of diversity Terry Lindsay said. Still, 40 percent of incoming freshman were students of color in fall 2011, he said.

Like administrators at other highly diverse schools, Lindsay has heard concern expressed that North Park’s commitment to racial, ethnic, and socio-economic diversity will compromise its academic standards.

“When you intentionally go after first generation college students, they come with their fair share of challenges,” he said. “They don’t know how to seamlessly transition from high school to college. They may … struggle academically with the curriculum. Because we know that, we are very intentional about putting measures and tools in place to make sure all of these students achieve success.”

Scales said there is “a lot of racism” around the issue. When he hears that Nyack is “watering down” academics in favor of diversity, he gives critics an opportunity to reflect on the offensiveness of that perspective and tells them: “We’ve taken that issue off the table.” Additionally, Nyack has pursued every specialized accreditation available for its programs, Scales said, to insure academic rigor.

Terry Lindsay: 'Social justice is key to North Park efforts.'

Like several other schools, North Park offers a program for incoming students to help them navigate the transition to college life. The Compass Scholars program identifies students who are potentially at risk and brings them to campus prior to their first semester, Lindsay said. They are given enrichment activities and academic skill development activities that are designed to help them acclimate.

The school also employs an Early Alert Reporting System that allows faculty to identify students who are at risk in their classes. “An EARS form is done online and that information automatically goes to student development and then they intervene immediately,” said Lindsay.

North Park is affiliated with the Evangelical Covenant Church and its commitment to first-generation students reflects the denomination’s social justice focus, Lindsay said. “Our decision to remain a college that’s committed to urban education, to remain a college that’s committed to our Christian values, and to strengthen our efforts around diversity are all grounded in what the Evangelical Covenant … has always been about,” he said.

“North Park has made great strides, I believe because they have linked [diversity] to their mission,” said Perez.

Reconnecting With a Proud Legacy

Unlike Lipscomb and other Christian colleges that early in their histories adhered to a policy of segregation and barred African Americans from enrolling, Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, prides itself on in its abolitionist history. Wheaton’s new president Philip Ryken told UrbanFaith many would agree that the school’s legacy was “squandered” at times, particularly in the twentieth century, “through a lack of intentionality about racial reconciliation” that he thinks was “pervasive” in the evangelical community.

Ryken has had a lot of conversations with students of color this year about what he calls “the good, the bad, and the ugly.” “Depending on what day it is, I see our situation at Wheaton either as a glass half full or as a glass half empty,” said Ryken. “There’s no doubt that we have a lot of ongoing progress to make, particularly in the openness of our student body as a whole to experiencing other cultures and also making space for the right kinds of open dialogues about race that really lead to deeper understanding.”

Philip Ryken: 'Wheaton's proud legacy was sometimes squandered.'

One of the positives Ryken sees is the 461 students of color among the 3,000 currently on campus. When he was a Wheaton student in the 1980s, there were less than 100, he said. Forty-nine percent of these students are Asian, 18 percent are African American, and 21 percent are Hispanic, Ryken said, and many of them serve in positions of leadership on campus.

“They’re really thriving in the use of their gifts on campus. They’re not marginalized, but really flourishing,” said Ryken.

Among the ongoing challenges he sees is that “nearly all” students of color at Wheaton say other students and/or faculty have “made assumptions about them” or “made comments that were hurtful in ways that maybe even the person who said it didn’t understand.” Some students are “ready for a dialogue about ethnicity, race, culture, and the gospel,” he said, while others are “indifferent.”

The residence life staff at Wheaton is intentionally being trained to address issues of ethnicity, Ryken said, and talks are underway about designating one of Wheaton’s residence houses as an intentionally diverse living community. Additionally, a faculty development day may be set aside next year to hear from students of color as part of a proactive approach to fostering healthy dialogue about race in Wheaton’s classrooms. Although there has been a long-standing and comprehensive diversity requirement for all of Wheaton’s courses, Ryken said the faculty recognizes its need to grow in “cross-cultural competency.”

When people ask Ryken why Wheaton is re-prioritizing race, he says the most important thing to tell them is, “because this is what Scripture teaches.” But, he said, it also helps to be able to say, “because this is the school that we were founded to be.”

Reaching for the Future

Glen Kinoshita: 'Students need to be engaged on multiple levels.'

For our previous article, Glen Kinoshita, director of multi-ethnic programs and development at Biola University in La Mirada, California, told us that it can be challenging for students to shift their frame of reference, but if it is done with regularity and in community, they can grow in their “ethnic identity development.”

This takes time, Kinoshita said, and students need to be engaged on multiple levels. Individual reflection, reading articles and books, watching documentary films, and getting plugged into a larger group dialogue to gain perspective and build relationships are among the activities he suggests. Kinoshita even formed Multi Ethnic Film Productions at Biola to stimulate “thought, dialogue, and change within Christian higher education.”

While these and other Christian college leaders press ahead in embracing a multi-racial future, friends at secular institutions tell Joel Perez that the diversity conversation is changing. Instead of being driven by a Black-White binary, it has become much more nuanced. Religious diversity, multi-ethnicity, and sexual orientation are increasingly at the forefront of the discussion. Some of the schools we’ve highlighted here are already grappling with these issues. Others have only just begun.

by Dr. Vincent Bacote | Apr 10, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

SEEKING HEALING: On March 31, congregants prayed for slain Florida teen Trayvon Martin and his shooter, George Zimmerman, during a service at the First Church of Seventh Day Adventists in Washington, D.C. The prayer was focused on racial healing and asked that people exercise patience to allow the judiciary to follow its course to bring about justice. (Photo: Nicholas Kamm/Newscom)

Many words have been and will be written about the death of Trayvon Martin, and the cocktail of grief, outrage, and confusion will likely linger long after the matter is resolved in one way or another. The circumstances of this unfortunate event have directed our attention to some of the challenges we face as a nation and as human beings, with considerable focus on the persistent difficulties connected to race. Whether or not Martin was racially profiled, this tragedy presents the opportunity to take paths that will lead us to better expressions of our humanity.

As director of Wheaton College’s Center for Applied Christian Ethics I had the privilege of participating in an event entitled “Civil War and Sacred Ground: Moral Reflections on War” (co-sponsored with The Raven Foundation). Two points raised at this thought-provoking conference can be helpful as we consider the long shadow of our history with race, particularly for followers of Christ. First, I continue to hear the echo of the following statement (paraphrased here) from Luke Harlow of Oakland University: “At the time of the Civil War, white supremacy was essentially held as an article of faith.” By this, he meant most citizens in the United States, North and South. Upon hearing this, I thought, No wonder it is so difficult for us to overcome the negative legacy of race.

The fact that racial superiority was so unquestioned suggests that the social, cultural, and political fabric of the Modern West in general and the United States in particular was constructed with a view of human beings that could be generalized as “whites” (or ethnic Europeans, who admittedly had their clashes) and “others.” Though the latter were identified according a range of racial categories, they definitely were not regarded as equal to “whites,” even among Christians. Of course there were those who did regard all humans as equal, but this was truly a minority report.

While many changes have occurred in the 150 years since the Civil War began, race consciousness remains in our social and cultural DNA like a stubborn mutation, rendering it difficult for us to truly and consistently regard “others” as equal before the eyes of God and fully human. This problem of otherness is not new, but it has manifested in a particularly malevolent fashion in the construction of racial identity. Today, this means that though great changes have occurred that would have been unimaginable 150 years ago, much more needs to change if we are to really live together as caring neighbors, at least in the church if not elsewhere. Yet this is an area where Christians continue to struggle, and many find themselves exhausted in reconciliation efforts.

The stubbornness of our race problem could lead us to despair, but taking a long view in light of where we have come from instead reminds us that we must have great patience as we pursue fundamental change. This patience is not the twin of apathy, but the disposition of steadiness and faithfulness in the face of at times imperceptible transformation. Change has occurred and can occur again.

Second, and more briefly, Dr. Tracy McKenzie, chair of Wheaton College’s history department, urged us to consider the difference between moral judgment and moral reflection. Whether it is the views held by most citizens 150 years ago or today in moments of racial conflict, moral judgment is the easy path which leads us to say “I can’t believe they held/hold such views and did such things.” Moral judgment keeps us separate from those we find reprehensible or disappointing. With moral reflection, while we may be surprised, disappointed, or offended by the ideas and actions we see in others, we are also prompted to consider our own moral architecture. In the question of race and otherness, moral reflection helps us to ask: What would I have thought if I were living at that time; how do I think about those that I readily regard as “other” from me; and does someone’s “otherness” make it easier for me to conclude that they are deficient in their humanness in some way and thus make it easier for me to disregard Christ’s command to love my neighbor as myself?

Moral reflection does not refuse to identify moral failings, but it leads us to look for them in places we might not peer otherwise. Moral reflection can prompt us to look at ourselves, our church, and our world in a way that brings us to a place of repentance that leads to transformation of life and even society.

Steady, faithful patience and moral reflection hardly exhaust our strategies for changing how we honor God in addressing the problem of race, but I find them helpful. What helps you?

This essay was adapted from an article at The Christian Post and was used by permission.

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.