A Black history primer on African Americans’ fight for equality – 5 essential reads

As the father of Black history, Carter G. Woodson had a simple goal – to legitimize the study of African American history and culture.

To that end, in 1912, shortly after becoming the second African American after W.E.B. Du Bois to earn a Ph.D. at Harvard, Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915.

More than 100 years later, Woodson’s goal and his work detailing the struggle of Black Americans to obtain full citizenship after centuries of systemic racism is still relevant today.

As dozens of GOP-controlled state legislatures across the U.S. have either considered or enacted laws restricting how race is taught in public schools, The Conversation U.S. has published numerous stories over the years exploring the rich terrain of Black history – and the never-ending quest to form what the Founding Fathers called a more perfect union.

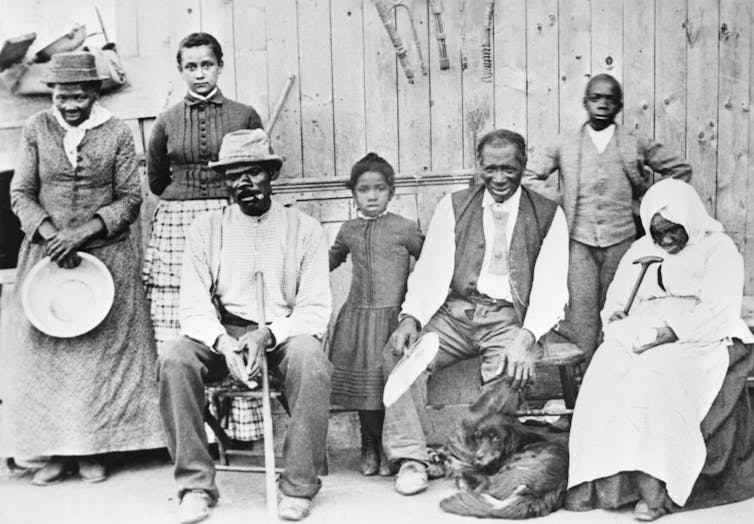

1. From the Underground Railroad to Civil War battlefields

Armed with a deep faith, Harriet Tubman is most famous for her successes along the Underground Railroad, the interracial network of abolitionists who enabled Black people to escape from slavery along secret routes in the South to freedom in the North and Canada.

But Tubman’s activities as a Civil War spy are less well known.

As historian and Tubman biographer Kate Clifford Larson wrote, Tubman’s devotion to America’s promise of freedom endured, despite suffering decades of enslavement and second-class citizenship.

“I had reasoned this out in my mind,” Tubman once said. “There was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death. If I could not have one, I would have the other; for no man should take me alive.”

2. Juneteenth and the myths of emancipation

As a scholar of race and colonialism, Kris Manjapra wrote that Emancipation Days – Juneteenth in Texas – are not what many people think.

“Emancipations did not remove all the shackles that prevented Black people from obtaining full citizenship rights,” Manjapra noted. “Nor did emancipations prevent states from enacting their own laws that prohibited Black people from voting or living in white neighborhoods.”

Between the 1780s and 1930s, over 80 emancipations from slavery occurred, from Pennsylvania in 1780 to Sierra Leone in 1936.

In fact, there were 20 separate emancipations in the United States alone from 1780 to 1865.

3. An image of a lynching found in a family photo album

As director of the Lynching in Texas project, historian Jeffrey L. Littlejohn provided the very kind of analysis that Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and Republican legislators in Texas want to ban from public schools.

Among the many documents and relics Littlejohn has received, one package stood out. Inside was a family album of photographs filled with the usual images of memories – a vacation, a wedding anniversary dinner – but also, one of the lynching of a Black man.

During the Jim Crow era, lynchings occurred regularly in Texas – with 16 in 1922 alone.

But in 2021, the GOP-controlled state Legislature in Texas enacted a law prohibiting K-12 educators from teaching that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from … the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”

In other words, as Littlejohn wrote, “this interpretation holds that slavery, racism and racism’s deadly manifestation, lynching, did not serve as systemic forces that shaped Texas history but were instead aberrations.”

The photo album serves as a direct challenge to that interpretation.

4. Black soldiers fight racism and Nazis during World War II

In his book “Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad,” historian Matthew Delmont explored the idea of Black patriotism and how many Black soldiers saw their service as a way to demonstrate the capabilities of their race.

Prompted by the Pittsburgh Courier, an influential Black newspaper during the 1940s, Delmont wrote that Black Americans rallied behind the Double V campaign during the war – victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home.

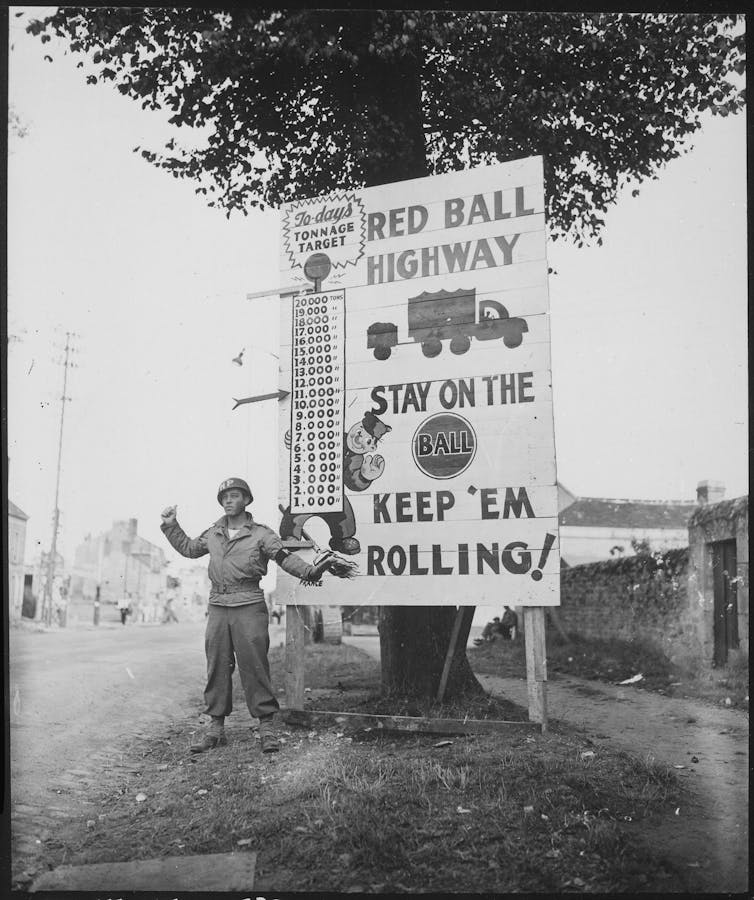

During the war, the Red Ball Express, the Allied forces’ transportation unit that delivered supplies to the front lines, was one example of such exceptional performance.

From August through November 1944, the mostly Black force moved more than 400,000 tons of ammunition, gasoline, medical supplies and rations to battlefronts in France, Belgium and Germany.

5. An NBA champion’s cerebral fight for equal rights

In his biography of Bill Russell, “King of the Court,” Aram Goudsouzian wrote that the NBA champion sought to find worth in basketball amid the racial tumult of the civil rights movement.

He emerged from that crucible by crafting a persona that one teammate called “a kingly arrogance.”

Russell, who died July, 31, 2022, was the NBA’s first Black superstar, its first Black champion and its first Black coach.

As a civil rights activist, Russell questioned the nonviolence philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr. and defended the militant ideas of Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam. He refused to accept segregated accommodations in the Deep South and recalled instances of police brutality during his childhood in Oakland, California.

“It’s a thing you want to scream,” Russell wrote. “I MUST HAVE MY MANHOOD.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.![]()

Howard Manly, Race + Equity Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.