by Edward Ford Jr. | Aug 19, 2024 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Social Justice |

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

These words are among the opening lines of the Declaration of Independence. It is a bold declaration, and one that we as a nation should in every era strive towards. However, the reality is that we have yet to attain this ideal. These words written should remind each of us that we are made in the Imago Dei – the image of God. We are entitled to inalienable rights. What is an inalienable right you might wonder? It is a right to freedom; a right to have your voice heard; a right to have clean air, water, food and housing. These rights were given to us by our Creator and therefore, no government should be able to deny them. Again, we have had to strive in many ways to live up to this standard. The horrific legacy of treatment towards indigenous people, race-based chattel-slavery, lynching, black codes, Jim Crow, Voter Suppression, Red-Lining, and Mass Incarceration are indicators to us that we are still on the journey to living up to what was written in our Declaration. Within each generation there is a remnant of people of good faith who must decide to call out the present injustice and reject evil and wrongdoing at every angle.

Sojourner Truth Memorial in Florence, Massachusetts.

Lynne Graves, CC BY-ND

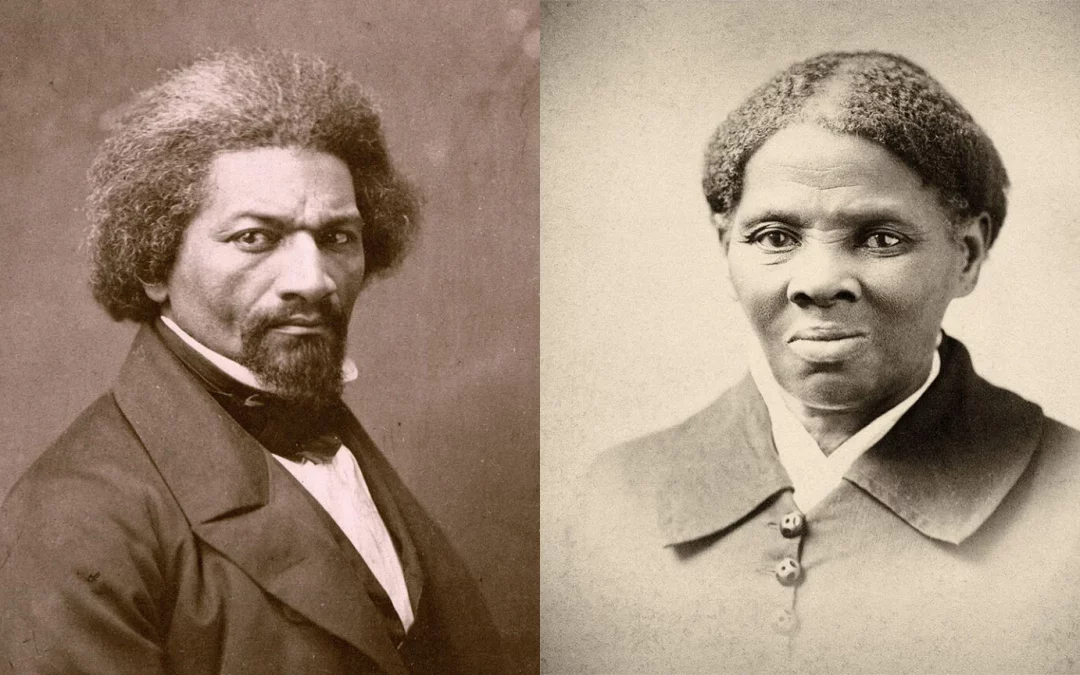

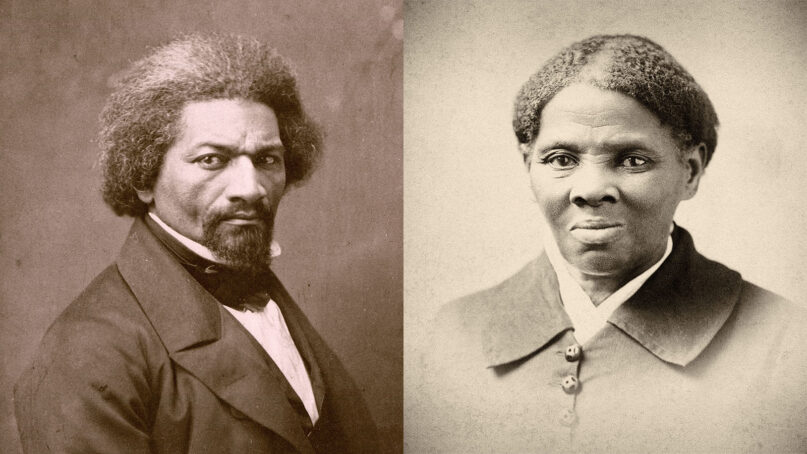

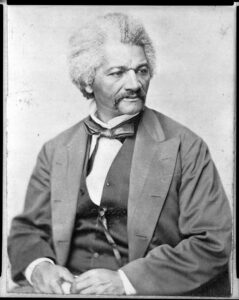

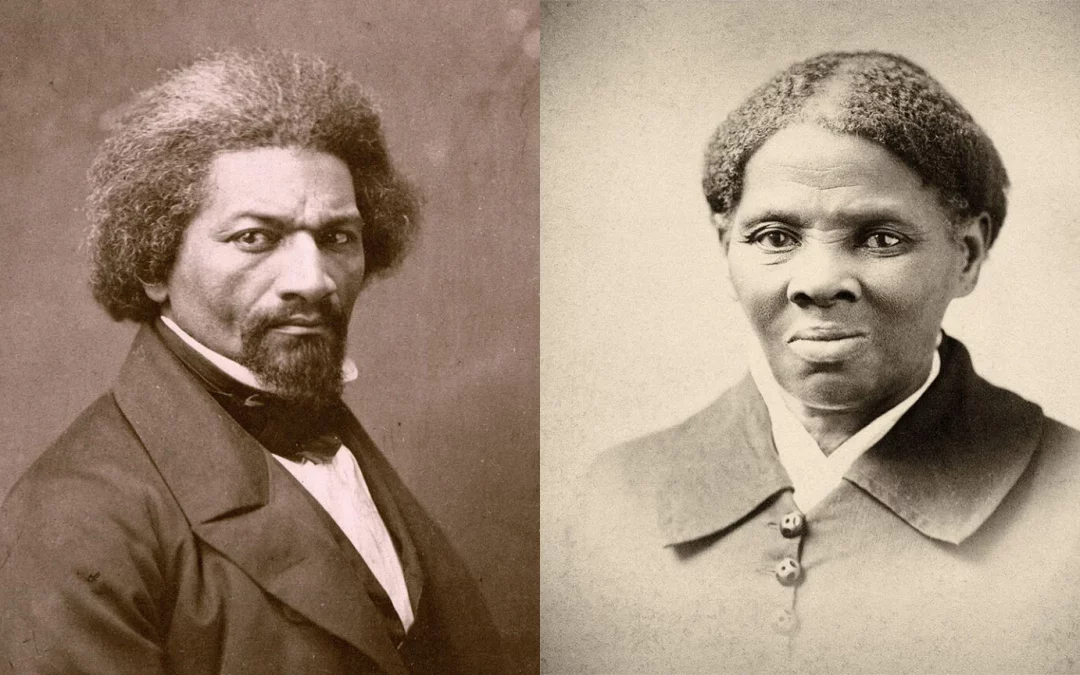

During the Abolition Movement, Frederick Douglas and Sojourner Truth were among abolition leaders who were led by their deep Christian faith to push for the abolition of race-based chattel slavery. They looked to the Declaration of Independence as a document that applied the moral laws of creation to our newly formed nation and how all people ought to be treated. The use of the declaration was much a part of the argument for abolition, and rightfully so. The argument was to highlight blatant hypocrisies that were being ignored for the benefit of the planter class. The same argument was used during America’s 2nd Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s-60s. Our country is much familiar with the name of Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. How many of us truly know what was said in that speech besides “I have a dream”? The correct title of the speech that King delivered, was “Normalcy, Never Again.” Within this speech King is quoted saying, “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men – yes, black men as well as white men – would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” King was appealing to our nation’s better angels and trying to reveal to us the reality that we had not been true to what we wrote on paper. In his final speech, titled “I’ve been to the Mountaintop”, delivered before a Memphis crowd on April 3rd, 1968 the day before he was assassinated, King said “All we say to America is to be true to what you said on Paper”. King was referring back to our Declaration and the bold promises of liberty and justice for all we continue to tout to this very day.

I raise the example of King, Truth, and Douglas, as they were each Christian leaders who gave themselves to the plight of justice in their respective eras. The lives of these American Christians among many others give us a glimpse into how we as Christians can engage in the movement for justice from a biblical worldview in our society today. We must ask ourselves as Christians, how can we aid in helping our nation truly live up to its highest ideals of liberty and justice for all? How can we progress our nation towards valuing everybody as image bearers in and throughout our systems?

First we have to look back at the scriptures and principles of God’s Word. Jesus shares the story of the Good Samaritan in Luke chapter 10:25-37, for good reason. He is breaking down cultural barriers and helping those of his day to see one another as fellow image bearers. Earlier in the chapter Jesus effectively answers a religious law expert’s question regarding the greatest commandments (v. 27). Jesus essentially had the man answer his own question! The passage is as follows: “He answered, ‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’; and ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ ‘You have answered correctly,’ Jesus replied. “Do this and you will live.” But he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” This is when Jesus shares the famous Good Samaritan story with him and how he was the only one of three people to stop and help the person who had just been beaten and robbed on the side of the road. The exchange between the two continues. In verses 36-37, Jesus asks him, “Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” The expert in the law replied, “The one who had mercy on him.” Jesus told him, “Go and do likewise.”

This passage is timeless. It provides a view into God’s heart towards all of humanity, how Jesus came as the rendering of God’s mercy towards us, and how he requires us to show mercy to others. In Luke 4:18-19, Jesus makes his own opening declaration as he begins his three-and-a-half-year world-changing ministry. He says, “The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

We who carry on the Great Commission, who have a duty to spread the Gospel to all, must recognize we have to fulfill this duty in word and deed. The early church in the Book of Acts spread the Gospel and they also initiated humanitarian help to those in need. There are so many issues in our modern world today, that we as the body of Christ have the capability to impact in a positive way. From helping the unhoused, resolving food insecurity in entire communities, to pushing our policy makers to make healthcare more affordable, and taking numerous policy actions that will uplift all people. We are to be a voice for the voiceless. There is no greater place of refuge and strength for the weary, the broken and the hurting than the church today. We must live the Gospel through our actions and that includes standing up for the poor, the marginalized, and the oppressed of society.

Reverend Edward Ford Jr. is a Former Elected Official in Connecticut, a Community Advocate, Organizer, Healthcare Administrator, and Public Theologian. He is currently studying for a Master’s Degree in Divinity at Yale University in New Haven, CT.

Reverend Edward Ford Jr. is a Former Elected Official in Connecticut, a Community Advocate, Organizer, Healthcare Administrator, and Public Theologian. He is currently studying for a Master’s Degree in Divinity at Yale University in New Haven, CT.

Sources:

National Archives. The Declaration of Independence. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

Carla S. King and William M. King. “Be True to What you Said on Paper.” History Colorado. Jan. 14th, 2021. https://www.historycolorado.org/story/discourse/2021/01/14/be-true-what-you-said-paper

by Allen Reynolds, UrbanFaith Editor | Jan 31, 2023 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News |

Every Black History Month we see a million memes, quotes, and images of Black people who have played an important role in shaping the story and lives of black people in America. We have heard about Martin Luther King Jr., Harriett Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Rosa Parks more times than we can count. If we’ve grown up with good black history education which is rare in these yet to be United States of America, then we might know Booker T. Washington or Maya Angelou. We know there is an active attempt to publicly whitewash black history as though the systemic destruction, repression, and marginalization of our history wasn’t enough. As a result it becomes more important than ever to teach and tell Black History.

But in an attempt to reclaim our history, let us not forget the key role faith played in the lives of so many of our black leaders. There is a reason why belief in God and practice of faith were so key in the lives of many (but not all) people we talk about during Black History Month. So let’s lift up the faith of our black heroines and heroes this month as we continue to live out our own faith. Below are just some notable examples of historical moments and key black leaders who were influenced by their faith.

Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey was an abolitionist and former slave who planned and organized an armed slave rebellion to free the slaves in Charleston, SC. Charleston was the largest slave trading port in the United States during the early 1800s. He was the slave of a ship captain who won the lottery and paid for his own freedom with his earnings, but was not able to pay for his family’s freedom. As a result he became intent on ending the institution of slavery itself. Vesey was a worshipper and small group teacher at the African Church which became Mother Emmanuel AME Church, and his faith informed his advocacy for abolition.

He was inspired by the Haitian revolution and planned to flee to Haiti with the freed slaves after the rebellion. He inspired other abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, David Walker, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. It is well noted that the abolition of slavery was a result of the work of Christian abolitionists.

The Christianity of Vesey and David Walker after him did not advocate for passive waiting to slavery to end. As he read Isaiah, Amos, and especially Exodus he were convinced that armed rebellion could be used by God to bring freedom to enslaved Africans. He began to preach a radical liberation theology from the Old Testament almost exclusively as he prepared for rebellion. Denmark Vesey resurfaced as a popular figure in recent years in the aftermath of the horrendous shooting at Mother Emmanuel AME Church in 2016.

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer was the founder and vice-chairperson of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which successfully unseated the all-white Mississippi delegation at the Democratic Party’s convention in 1968. This and other efforts earned her the title “First Lady of Civil Rights.”

In 1962, Fannie Lou became involved with the Civil Rights Movement when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee held a meeting in Ruleville, Mississippi. She and 17 others went to the county courthouse and tried to register to vote. Because they were African American, they were given an impossible registration test which they all failed. Fannie Lou’s life became a living hell. She was threatened, shot at, cursed and abused by angry mobs of white men including being beat almost to death by the police and imprisoned in Mississippi in 1963 for registering to vote.

Fannie Lou Hamer often sang spirituals at rallies, protests, and even in jail. Her faith in God is what she felt carried her through those difficult experiences. She quoted the Bible to shame her oppressors, encourage her followers, and hold her ministerial colleagues in the SCLC and SNCC accountable. She was a devout member of William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, and let her faith permeate everything she did.

Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander, JD is a civil rights lawyer and advocate, a legal scholar and the author of the New York Times best seller “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.” The book helped to start a national debate about the crisis of mass incarceration in the United States and inspired racial-justice organizing and advocacy efforts nationwide.

Alexander performed extensive research on mass incarceration, racism in law and public policy, and racial justice to write her book published in 2010. She has lectured and taught widely on her work as a professor of law and religion at Stanford University, The Ohio State University, and Union Theological Seminary. The New Jim Crow became a foundational text for many of the reforms being advocate for by various organizations involved in the recent push for criminal justice reform and the movement for black lives.

Alexander was driven by her faith to advocate for justice system reforms, believing that God called her to it and seeing it as her reasonable service. Her faith drives her advocacy for justice for the marginalized, care and compassion for all people, and teaching. She feels as though her work in law and faith are inextricably linked, and that people of faith are poised to serve one of the most important roles in changing the system. She is currently a visiting professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York exploring the spiritual and ethical dimensions of the fight against mass incarceration.

https://www.nps.gov/people/denmark-vesey.htm

https://www.pbs.org/thisfarbyfaith/people/denmark_vesey.html?pepperjam=&publisherId=120349&clickId=3860507074&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_campaign=affiliate

https://urbanfaith.com/2021/10/faith-endurance-of-civil-rights-activist-fannie-lou-hamer-revealed-in-new-biography.html/

https://divinity.yale.edu/news/michelle-alexander-mass-incarceration-believing-possibility-redemption-and-forgiveness

https://www.nytimes.com/by/michelle-alexander

A Salute to Black Civil Rights Leaders, Richard L. Green, Chicago: Empak Enterprises,1987, p. 11

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 20, 2022 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Heritage |

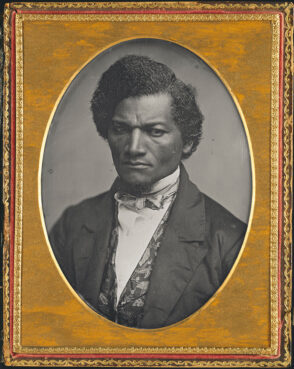

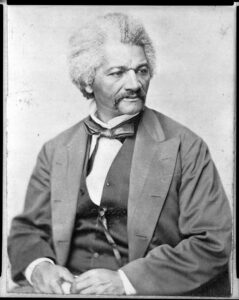

(RNS) — Frederick Douglass called the Bible one of his most important resources and was involved in Black church circles as he spent his life working to end what he called the “peculiar institution” of slavery.

Harriet Tubman sensed divine inspiration amid her actions to free herself and dozens of others who had been enslaved in the American South.

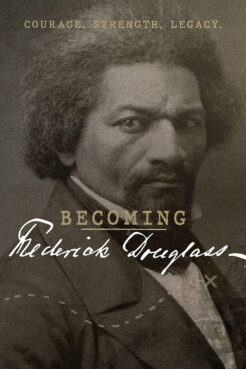

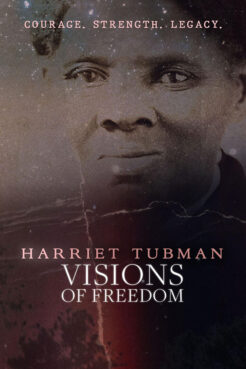

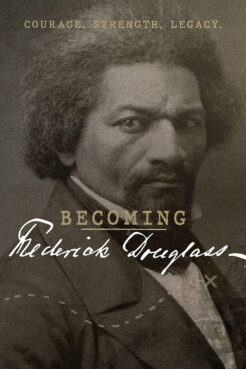

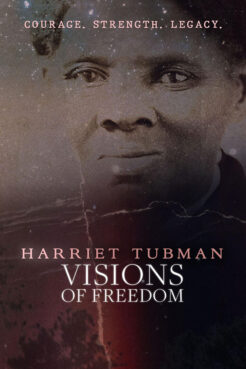

The two abolitionists are subjects of a twin set of documentaries, “Becoming Frederick Douglass” and “Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom,” co-productions of Maryland Public Television and Firelight Films and released by PBS this month (October).

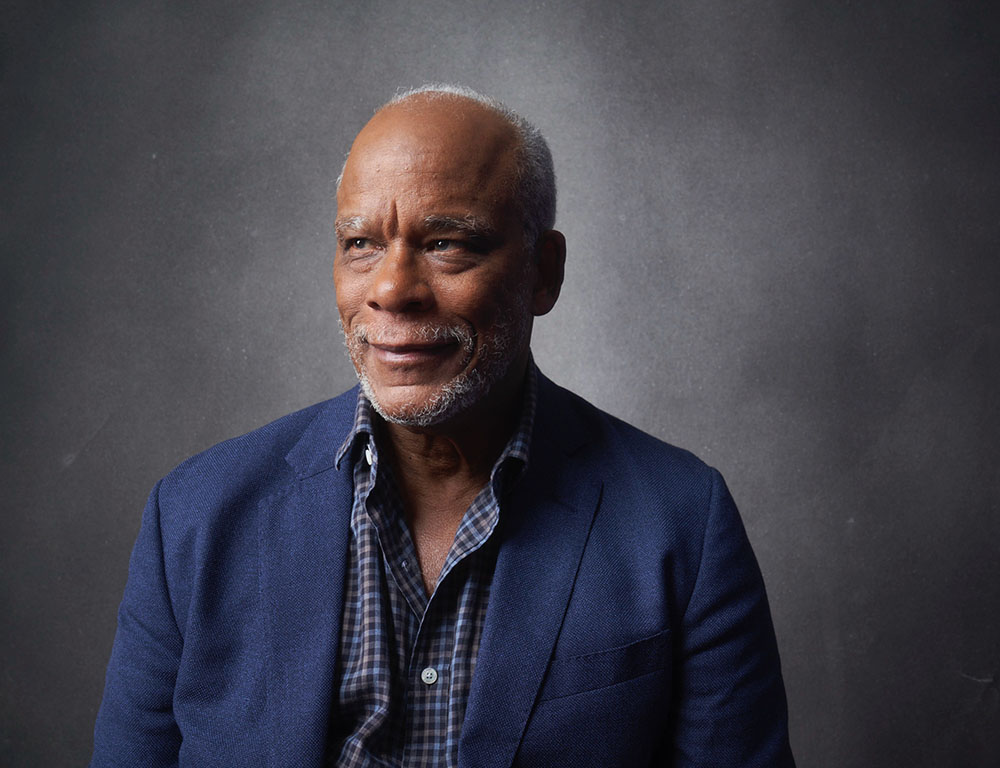

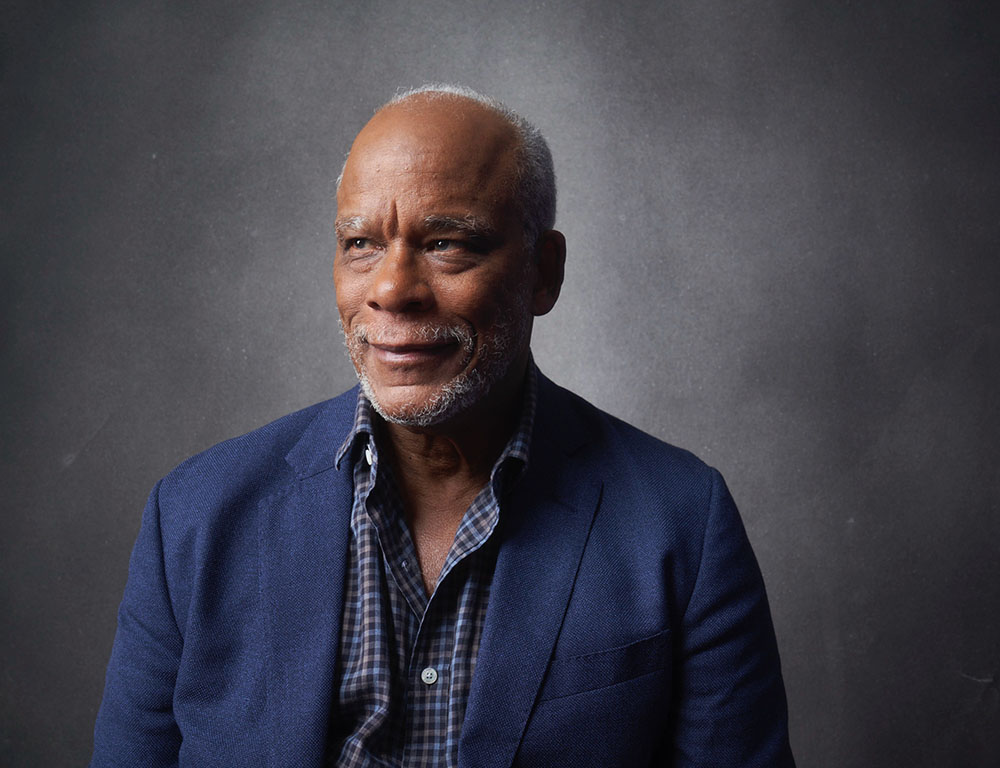

“I think that the faith journey of both Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass were a huge part of their story,” Stanley Nelson, co-director with Nicole London of the two hourlong films, said in an interview with Religion News Service.

“Religion for both Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass was the foundation in many ways of who they are.”

Stanley Nelson. Photo by Corey Nickols

The films, whose production took more than three years in part due to a COVID-19 hiatus, detail the horrors of slavery both Tubman and Douglass witnessed. Tubman saw her sister being sold to a new enslaver and torn away from her children. A young Douglass hid in a closet as he watched his aunt being beaten. They each expressed beliefs in the providence of God playing a role in the gaining of their freedom.

Scholars in both films spoke of the faith of these “original abolitionists,” as University of Connecticut historian Manisha Sinha called people like Tubman, who took to pulpits and lecterns as they strove to end the ownership of members of their race and sought to convince white people to join their cause.“The Bible was foundational to Douglass as a writer, orator, and activist,” Harvard University scholar John Stauffer told Religion News Service in an email, expanding on his comments in the film about the onetime lay preacher. “It influenced him probably more than any other single work.”

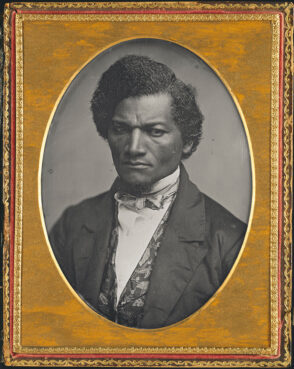

Frederick Douglass, circa 1847-52. Photo by Samuel J. Miller, courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago Stauffer said the holy book, which shaped Douglass’ talks and writings, was the subject of lessons at a Sunday school he organized to teach other slaves.

“It’s impossible to appreciate or understand Douglass without recognizing the enormous influence the Bible had on him and his extraordinary knowledge of it,” Stauffer added.

Actor Wendell Pierce provides the voice of Douglass in the films, quoting him saying in an autobiography that William Lloyd Garrison’s weekly abolitionist newspaper The Liberator “took a place in my heart second only to the Bible.”

The documentary notes that Douglass was part of Baltimore’s African Methodist Episcopal Church circles that included many free Black people. Scholars say he met his future wife Anna Murray, who encouraged him to pursue his own freedom, in that city.

“The AME Church was central in not only creating a space for African Americans to worship but creating a network of support for African Americans who were committed to anti-slavery,” said Georgetown University historian Marcia Chatelain, in the film.

The Douglass documentary is set to premiere Tuesday (Oct. 11) on PBS. It and the Tubman documentary, which first aired Oct. 4, will be available to stream for free for 30 days on PBS.org and the PBS video app after their initial air dates. After streaming on PBS’ website and other locations for a month, the films, which include footage from Maryland’s Eastern Shore where both Douglass and Tubman were born, will then be available on PBS Passport.

- Poster for “Becoming Frederick Douglass.” Courtesy image

- Poster for “Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom.” Courtesy image

The Tubman documentary opens with her words, spoken by actress Alfre Woodard.

“God’s time is always near,” she says, in words she told writer Ednah Dow Littlehale Cheney around 1850. “He set the North Star in the heavens. He gave me the strength in my limbs. He meant I should be free.”

Tubman, who early in life sustained a serious injury and experienced subsequent seizures and serious headaches, often had visions she interpreted as “signposts from God,” said Rutgers University historian Erica A. Dunbar in the film.

Portrait of Harriet Tubman taken in Auburn, New York. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress. The woman known as “Moses” freed slaves by leading them through nighttime escapes and later as a scout for the Union Army in the Civil War.

“She never accepted praise or responsibility, even, for these great feats,” Dunbar said. “She always saw herself as a vessel of her God.”

But, nevertheless, praise for Tubman came from Douglass, who noted in an 1868 letter to her that while his work was often public, hers was primarily in secret, recognized only by the “heartfelt, ‘God bless you’” from people she had helped reach freedom.

Nelson, a religiously unaffiliated man who created films about the mission work of the United Methodist Church early in his career, said the documentary helps shed light on the importance faith held for Tubman.

“It’s something that most people don’t know and so many people who see the film for the first time are kind of surprised at that,” he said in an interview. “She felt she was guided by a divine spirit and the spirit told her what to do.”

by Barnett Wright | Sep 21, 2022 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Social Justice |

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. (AP) — When an initially blinded, and nearly lifeless, 12-year-old girl found in the rubble of a church bombing was wheeled onto the 10th floor of University Hospital in Birmingham nearly 60 years ago, one of the first people to tend to the child was Rosetta “Rose” Hughes, a nurse.

It was Hughes who stayed with Sarah Collins, the “fifth little girl” in the bombing, until a doctor arrived on that momentous Sunday, as an unforgettable chapter was being etched into the city’s history.

Hughes was on duty on Sept. 15, 1963, when a bomb demolished the 16th Street Baptist Church, killing Addie Mae Collins, 14; Denise McNair, 11; Carole Rosamond Robertson, 14; and Cynthia Wesley, 14 and injuring dozens of parishioners.

One of the surviving girls was Sarah Collins, sister of Addie Mae. On that Sunday, staff at the emergency clinic at University Hospital received the bodies of the four children killed and tended to scores of others who were injured. Sarah Collins was among the wounded, and one of the first to see her was Hughes.

“When I saw her that Sunday, … she was just covered with soot and ashes (and blood),” Hughes recalled in an exclusive interview with The Birmingham Times. “(It) looked like she was gone. … I thought she wasn’t going to wake up. … She was not moving.”

That was 59 years ago.

On Thursday, Birmingham commemorated the explosion that proved to be a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement, became a catalyst for change in the United States, and ultimately prompted global efforts for equality and human rights.

Hughes, who turns 101 in October and still lives in Birmingham, is believed to be one of the last remaining workers on duty at the hospital the day of the bombing.

Last month, for the first time since the bombing, Hughes and Rudolph, now 71, reunited for their first one-on-one, lengthy discussion of the events on that pivotal day in world history.

“It’s more than a blessing to meet her because she took care of me,” Rudolph said during the interview. “When I was younger, I didn’t know how she looked or anything because I was practically blind then. So, just to see her now and know her is a blessing. She’s looking real good.

Hughes recalled working on the 10th floor of University Hospital, which was known as the “Eye” floor, when young Sarah was wheeled in.

“I remember they brought her to the emergency room, and I was working on the Eye floor. We had the surgery up there, and they sent her to eye surgery. … She was on a stretcher, and I took care of her until they called the doctor to come in,” said Hughes, who recalls the doctor’s name only as “Pearson” and that he arrived with a toddler.

Medical staff from across the city were being called in to help with the influx of patients. Many of the doctors were scheduled to be off that weekend, and that likely included Dr. Pearson, who came to the hospital with his son. While Hughes could not remember the doctor’s first name, University of Alabama at Birmingham records show a “Dr. Robert S. Pearson” as a resident in ophthalmology at the facility in the early 1960s.

“It was a Sunday morning, and the doctor’s wife had gone to church, so he was watching the baby and had to bring him (to the hospital). … I babysat while (Dr. Pearson) checked on Sarah,” Hughes recalled.

“(Dr. Pearson) came back out and sent her back downstairs to the where she was examined at first. … They took her back on a stretcher. She was still asleep … and I didn’t have to do anything. I just had to watch her. She was also covered with ashes and smoke.”

Even though she was 12 at the time of the bombing, Collins-Rudolph, still has vivid memories of what happened.

“That’s one day I will never forget,” she said. “I remember, you know, when they operated on my eyes. … I remember when they took the glass out of my eyes, glass from my face. … The doctor had told me there were about 20 to 26 pieces of glass in my face altogether.

“I know when the doctor operated on my eyes, they put this bandage on it. … Maybe about a week later, they took the bandage off. At first, the doctor asked me, ‘What do you see out of your left eye?’ I told him, ‘I just see a little light.’ He asked me the same question (about my right eye). I said, ‘I can’t see anything.’ So, he said I was blinded instantly in my right eye.

“When (the doctor) was talking to my mother, I remember hearing him tell her that eventually I would start seeing out of my left eye because I was real young and the sight would start coming back. When I was getting ready to leave the hospital, I remember (the doctor) telling (my mother) to bring me back in February because they were going to have to remove my right eye, and that’s what they did. I went back in February, and that’s when they removed my right eye and fit me with a prosthetic.”

Sarah has had problems with her eyesight for the past 59 years. She developed glaucoma in her left eye and was initially given drops for the eye.

“That didn’t work too good, and they tried another drop. It didn’t work too good either, so they tried a third drop,” she recalled. “When the drops stopped doing any good, (the doctor) said he would have to operate and give me an incision in that (left) eye. They put an incision in there to drain the fluid. … If he had not done that, I would have gone blind.”

Even today, Rudolph still must visit an eye doctor every six months.

“I had to pay for that out of my own pocket,” she said. “I would always wonder to myself, … ‘I was in that bombing, and I got hurt. How come I had to foot these bills by myself when it wasn’t my fault?’”

While the state apologized to Rudolph two years ago, it hasn’t yet honored her request for restitution.

At the reunion with Hughes, husband George Rudolph, who has been at Sarah Rudolph’s side for the past two decades and knows about survival after his first tour of duty as a 19-year-old during the Vietnam War, said his wife has strength he has not seen.

“For my wife to survive what she went through and not hold any animosity toward the KKK because she forgave them, that’s a strong person,” he said. “She didn’t want to hold her hatred in her heart for those Klansmen. When she said, ‘I forgive you,’ that was such a powerful statement. Very powerful. … She is just a strong Black lady and amazing. I love my wife. I thank God for Sarah.”

Reverend Edward Ford Jr. is a Former Elected Official in Connecticut, a Community Advocate, Organizer, Healthcare Administrator, and Public Theologian. He is currently studying for a Master’s Degree in Divinity at Yale University in New Haven, CT.

Reverend Edward Ford Jr. is a Former Elected Official in Connecticut, a Community Advocate, Organizer, Healthcare Administrator, and Public Theologian. He is currently studying for a Master’s Degree in Divinity at Yale University in New Haven, CT. Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander