Fannie Lou Hamer recorded 20 songs her mother taught her

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: RSS

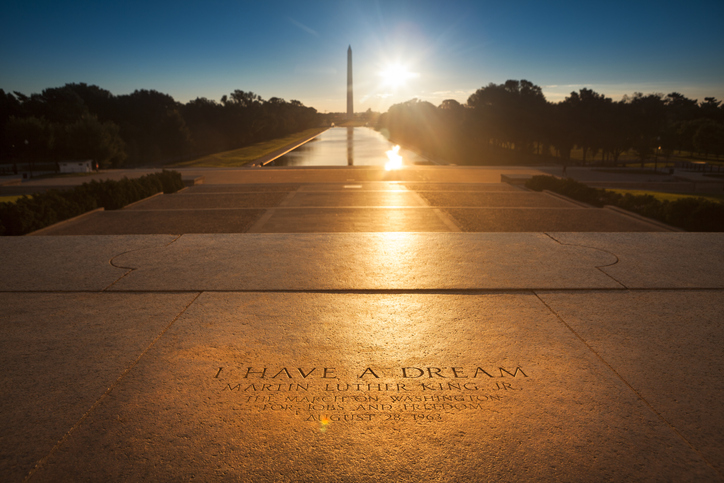

Every Black History Month we see a million memes, quotes, and images of Black people who have played an important role in shaping the story and lives of black people in America. We have heard about Martin Luther King Jr., Harriett Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and Rosa Parks more times than we can count. If we’ve grown up with good black history education which is rare in these yet to be United States of America, then we might know Booker T. Washington or Maya Angelou. We know there is an active attempt to publicly whitewash black history as though the systemic destruction, repression, and marginalization of our history wasn’t enough. As a result it becomes more important than ever to teach and tell Black History.

But in an attempt to reclaim our history, let us not forget the key role faith played in the lives of so many of our black leaders. There is a reason why belief in God and practice of faith were so key in the lives of many (but not all) people we talk about during Black History Month. So let’s lift up the faith of our black heroines and heroes this month as we continue to live out our own faith. Below are just some notable examples of historical moments and key black leaders who were influenced by their faith.

Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey

Denmark Vesey was an abolitionist and former slave who planned and organized an armed slave rebellion to free the slaves in Charleston, SC. Charleston was the largest slave trading port in the United States during the early 1800s. He was the slave of a ship captain who won the lottery and paid for his own freedom with his earnings, but was not able to pay for his family’s freedom. As a result he became intent on ending the institution of slavery itself. Vesey was a worshipper and small group teacher at the African Church which became Mother Emmanuel AME Church, and his faith informed his advocacy for abolition.

He was inspired by the Haitian revolution and planned to flee to Haiti with the freed slaves after the rebellion. He inspired other abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, David Walker, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. It is well noted that the abolition of slavery was a result of the work of Christian abolitionists.

The Christianity of Vesey and David Walker after him did not advocate for passive waiting to slavery to end. As he read Isaiah, Amos, and especially Exodus he were convinced that armed rebellion could be used by God to bring freedom to enslaved Africans. He began to preach a radical liberation theology from the Old Testament almost exclusively as he prepared for rebellion. Denmark Vesey resurfaced as a popular figure in recent years in the aftermath of the horrendous shooting at Mother Emmanuel AME Church in 2016.

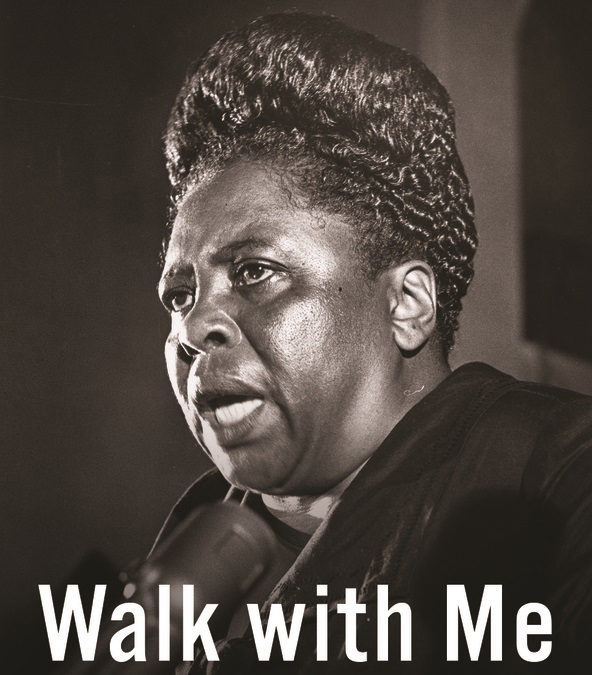

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer was the founder and vice-chairperson of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which successfully unseated the all-white Mississippi delegation at the Democratic Party’s convention in 1968. This and other efforts earned her the title “First Lady of Civil Rights.”

In 1962, Fannie Lou became involved with the Civil Rights Movement when the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee held a meeting in Ruleville, Mississippi. She and 17 others went to the county courthouse and tried to register to vote. Because they were African American, they were given an impossible registration test which they all failed. Fannie Lou’s life became a living hell. She was threatened, shot at, cursed and abused by angry mobs of white men including being beat almost to death by the police and imprisoned in Mississippi in 1963 for registering to vote.

Fannie Lou Hamer often sang spirituals at rallies, protests, and even in jail. Her faith in God is what she felt carried her through those difficult experiences. She quoted the Bible to shame her oppressors, encourage her followers, and hold her ministerial colleagues in the SCLC and SNCC accountable. She was a devout member of William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, and let her faith permeate everything she did.

Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander, JD is a civil rights lawyer and advocate, a legal scholar and the author of the New York Times best seller “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.” The book helped to start a national debate about the crisis of mass incarceration in the United States and inspired racial-justice organizing and advocacy efforts nationwide.

Alexander performed extensive research on mass incarceration, racism in law and public policy, and racial justice to write her book published in 2010. She has lectured and taught widely on her work as a professor of law and religion at Stanford University, The Ohio State University, and Union Theological Seminary. The New Jim Crow became a foundational text for many of the reforms being advocate for by various organizations involved in the recent push for criminal justice reform and the movement for black lives.

Alexander was driven by her faith to advocate for justice system reforms, believing that God called her to it and seeing it as her reasonable service. Her faith drives her advocacy for justice for the marginalized, care and compassion for all people, and teaching. She feels as though her work in law and faith are inextricably linked, and that people of faith are poised to serve one of the most important roles in changing the system. She is currently a visiting professor at Union Theological Seminary in New York exploring the spiritual and ethical dimensions of the fight against mass incarceration.

https://www.nps.gov/people/denmark-vesey.htm

https://www.pbs.org/thisfarbyfaith/people/denmark_vesey.html?pepperjam=&publisherId=120349&clickId=3860507074&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_campaign=affiliate

https://www.nytimes.com/by/michelle-alexander

A Salute to Black Civil Rights Leaders, Richard L. Green, Chicago: Empak Enterprises,1987, p. 11

(RNS) — Fannie Lou Hamer was an advocate for African Americans, women and poor people — and for many who were all three.

She lost her sharecropping job and her home when she registered to vote. She suffered physical and sexual assaults when she was taken to jail for her activism. And stories of her struggles reached the floor of the 1964 Democratic Convention — and the nation — when her emotional speech aired on television.

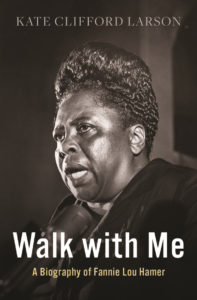

Historian Kate Clifford Larson has written a new book, “Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer,” that reveals details of the faith and life of Hamer, who was born 104 years ago Wednesday (Oct. 6) and died in 1977.

“Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer” by Kate Clifford Larson. Courtesy image

Inspired by young Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers who preached Bible passages about liberation at her church in Ruleville, Mississippi, in 1962, Hamer became a singer and speaker for equal rights and human rights.

“She crawled her way through extraordinarily difficult circumstances to bring her voice to the nation to be heard,” Larson told Religion News Service. “And she knew that she was representing so many people that were not heard.”

Larson spoke to RNS about Hamer’s faith, her favorite spirituals and how music helped the activist and advocate survive.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a biography of Fannie Lou Hamer and how would you describe her as a woman of faith?

I published a book about (Harriet) Tubman and Hamer is so similar to Harriet Tubman, only 100 years later. I decided to start looking into her life and thinking I should do a biography of Hamer. I just became hooked. There were so many similarities, and things I could see in Hamer that I just thought, we need to have a refresher about Fannie Lou Hamer and the strength of her character and how she survived such incredible adversity and found the same kind of solace that Harriet Tubman did — in her faith, in her family and the community — to keep going and fighting and to try to make the world a better place.

It seems she is relatively unknown in many circles despite the credit she’s given by civil rights veterans for her work.

It is curious that she is not well known broadly. And I hope that changes, because I think we need to look back sometimes to see how far we’ve come. And with Hamer, the things that happened to her — she faced the world by confronting that trauma, and that violence, without hate. And the only way she could do that was through her faith, and talking to God and saying: Where are you, what is happening here, give me the strength to carry this weight and to move forward. And she did. She knew hate could really destroy her — that feeling of hating the people that were trying to kill her and subjugate her. She managed to rise above it because she had a greater mission in front of her.

Why did you title the book “Walk With Me”?

The title is from the song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Mississippi, jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her. She asked Euvester to please sing with her because she needed to find strength and she needed God to be with her. So she sang that song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She needed to feel there was something bigger that would help her survive those moments where it wasn’t so clear she would survive. And I found it so powerful that she would do that. She survived that night and was able to get up and walk the next morning.

What other spirituals and gospel songs were particularly important to Hamer as she fought for voting rights and other social justice causes?

One of her favorites is “This Little Light of Mine.” She sang that everywhere, all the time. It’s kind of her anthem. There were some other spirituals, but really, most of the ones she sang a lot during the movement were those crossover folk songs, rooted in Christian spirituals, like “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” She grew up not only in a very strong church environment, the Baptist church, but she grew up in the fields of Mississippi where there were work songs in the fields, call and response songs. Where she grew up was actually the birthplace of the Delta blues music.

She also quoted the Bible to the people she differed with. Were there particular biblical lessons Hamer applied to her fight to help her fellow Black Mississippians?

She used the Bible in many different ways. She used it to shame her white oppressors who claimed also to be Christians, following the path of Christ. She would use the Bible and say: Are you following this path by what you’re doing to me, to my fellow community members and family members? And she used the Bible passages to remind Christian ministers: This is your job, and what are you doing up on that pulpit? You’re telling people to be patient. Well, in the Bible it says stand up and lead people out of Egypt.

You wrote about William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, Hamer’s congregation, throughout the book. What happened there, over the years as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups used it as a place for meetings, classes and rallies?

The church, the ministers participated in the movement and had meetings in that church at great risk to themselves and to the church, and in fact, the church was bombed a couple of times even though the fires were put out, fortunately, very quickly. There were residents in the community that took their lives and put them on the line. They were at great risk, to go to those meetings, to conduct those meetings, to go out and do voter registration drives. It was all centered on the church community because that was really the only community buildings in many of these places where people could meet together to have these discussions.

You said Hamer was at a crossroads as she first listened to those SNCC (pronounced “snick”) activists seeking more people to join their cause.

She experienced trauma, and she had been sterilized against her will — she didn’t give permission — and she had gone through this very deep depression, and it tested her faith. It tested her understanding of the world, and she came out of that and went to this meeting in Ruleville in 1962 and when she heard those young people and their passion and their willingness to put their lives on the line for her, she viewed them as the “New Kingdom.” So it was more than a crossroads for her. It was a moment where she could see the future in these young people, and she called them the “New Kingdom (right here) on earth.” If they were willing to stand up and risk their lives then she could, at 45, 46 years old, stand up herself. That was a crossroads. She made that choice to stand up, publicly, and move forward.