Black History month is a time for special celebration

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: RSS

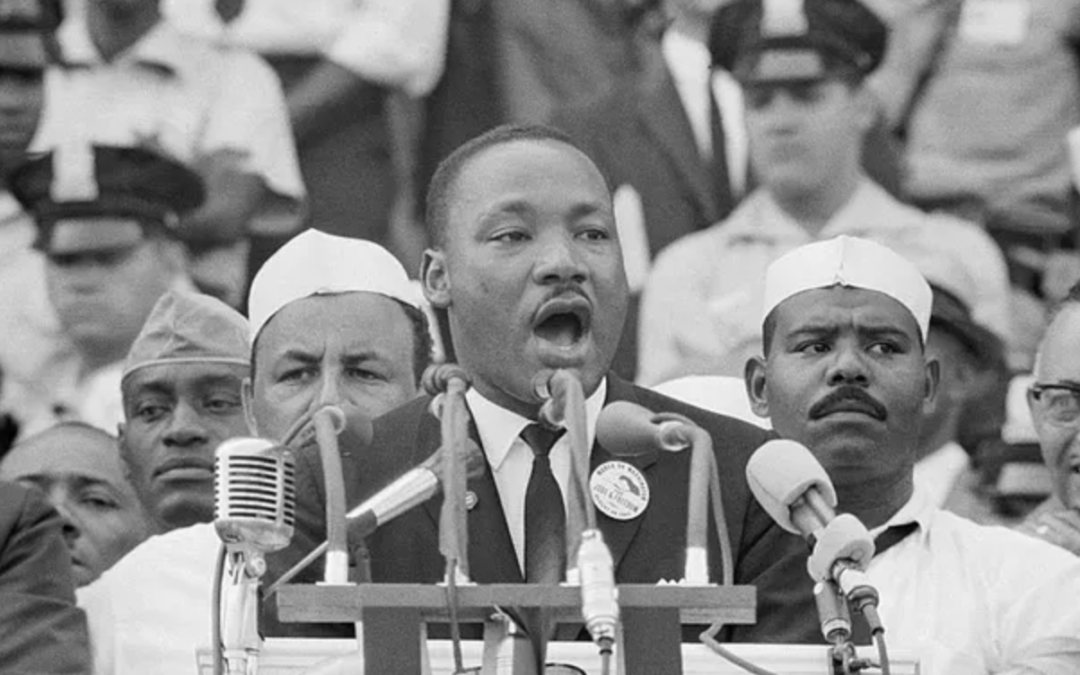

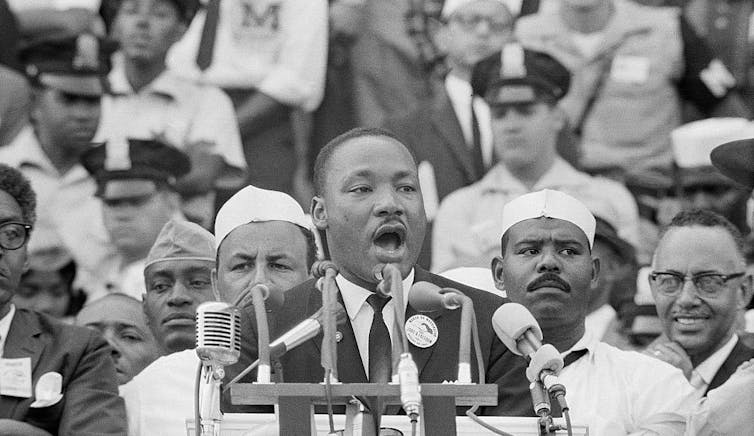

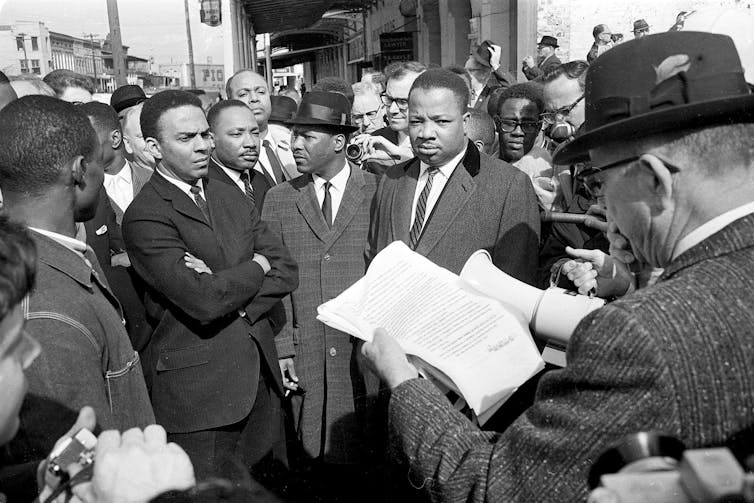

The name Martin Luther King Jr. is iconic in the United States. President Barack Obama mentioned King in both his Democratic National Convention nomination acceptance and victory speeches in 2008, when he said,

“[King] brought Americans from every corner of this land to stand together on a Mall in Washington, before Lincoln’s Memorial…to speak of his dream.”

Indeed, much of King’s legacy lives on in such arresting oral performances. They made him a global figure.

King’s preaching used the power of language to interpret the gospel in the context of black misery and Christian hope. He directed people to life-giving resources and spoke provocatively of a present and active divine interventionist who summons preachers to name reality in places where pain, oppression and neglect abound.

In other words, King used a prophetic voice in his preaching – the hopeful voice that begins in prayer and attends to human tragedy.

So what led to the rise of the black preacher and shaped King’s prophetic voice?

In my book, “The Journey and Promise of African American Preaching,” I discuss the historical formation of the black preacher. My work on African American prophetic preaching shows that King’s clarion calls for justice were offspring of earlier prophetic preaching that flowered as a consequence of the racism in the U.S.

First, let’s look at some of the social, cultural and political challenges that gave birth to the black religious leader, specifically those who assumed political roles with the community’s blessing and beyond the church proper.

In slave society, black preachers played an important role in the community: they acted as seers interpreting the significance of events; as pastors calling for unity and solidarity; and as messianic figures provoking the first stirrings of resentment against oppressors.

The religious revivalism or the Great Awakening of the 18th century brought to America a Bible-centered brand of Christianity – evangelicalism – that dominated the religious landscape by the early 19th century. Evangelicals emphasized a “personal relationship” with God through Jesus Christ.

This new movement made Christianity more accessible, livelier, without overtaxing educational demands. Africans converted to Christianity in large numbers during the revivals and most became Baptists and Methodists. With fewer educational restrictions placed on them, black preachers emerged in the period as preachers and teachers, despite their slave status.

Africans viewed the revivals as a way to reclaim some of the remnants of African culture in a strange new world. They incorporated and adopted religious symbols into a new cultural system with relative ease.

Despite the development of black preachers and the significant social and religious advancements of blacks during this period of revival, Reconstruction – the process of rebuilding the South soon after the Civil War – posed numerous challenges for white slaveholders who resented the political advancement of newly freed Africans.

As independent black churches proliferated in Reconstruction America, black ministers preached to their own. Some became bivocational. It was not out of the norm to find pastors who led congregations on Sunday and held jobs as schoolteachers and administrators during the work week.

Others held important political positions. Altogether, 16 African Americans served in the U.S. Congress during Reconstruction. For example, South Carolina’s House of Representatives’ Richard Harvey Cain, who attended Wilberforce University, the first private black American university, served in the 43rd and 45th Congresses and as pastor of a series of African Methodist churches.

Others, such as former slave and Methodist minister and educator Hiram Rhoades Revels and Henry McNeal Turner, shared similar profiles. Revels was a preacher who became America’s first African American senator. Turner was appointed chaplain in the Union Army by President Abraham Lincoln.

To address the myriad problems and concerns of blacks in this era, black preachers discovered that congregations expected them not only to guide worship but also to be the community’s lead informant in the public square.

Many other events converged as well, impacting black life that would later influence King’s prophetic vision: President Woodrow Wilson declared entrance into World War I in 1917; as “boll weevils” ravaged crops in 1916 there was widespread agricultural depression; and then there was the rise of Jim Crow laws that were to legally enforce racial segregation until 1965.

Such tide-swelling events, in multiplier effect, ushered in the largest internal movement of people on American soil, the Great “Black” Migration. Between 1916 and 1918, an average of 500 Southern migrants a day departed the South. More than 1.5 million relocated to Northern communities between 1916 and 1940.

A watershed, the Great Migration brought about contrasting expectations concerning the mission and identity of the African American church. The infrastructure of Northern black churches were unprepared to deal with the migration’s distressing effects. Its suddenness and size overwhelmed preexisting operations.

The immense suffering brought on by the Great Migration and the racial hatred they had escaped drove many clergy to reflect more deeply on the meaning of freedom and oppression. Black preachers refused to believe that the Christian gospel and discrimination were compatible.

However, black preachers seldom modified their preaching strategies. Rather than establishing centers for black self-improvement focused on job training, home economics classes and libraries, nearly all Southern preachers who came North continued to offer priestly sermons. These sermons exalted the virtues of humility, good will and patience, as they had in the South.

Three clergy outliers – one a woman – initiated change. These three pastors were particularly inventive in the way they approached their preaching task.

Baptist pastor Adam C. Powell Sr., the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ) pastor Florence S. Randolph and the African Methodist Episcopal bishop Reverdy C. Ransom spoke to human tragedy, both in and out of the black church. They brought a distinctive form of prophetic preaching that united spiritual transformation with social reform and confronted black dehumanization.

Bishop Ransom’s discontentment arose while preaching to Chicago’s “silk-stocking church” Bethel A.M.E. – the elite church – which had no desire to welcome the poor and jobless masses that came to the North. He left and began the Institutional Church and Social Settlement, which combined worship and social services.

Randolph and Powell synthesized their roles as preachers and social reformers. Randolph brought into her prophetic vision her tasks as preacher, missionary, organizer, suffragist and pastor. Powell became pastor at the historic Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. In that role, he led the congregation to establish a community house and nursing home to meet the political, religious and social needs of blacks.

The preaching tradition that these early clergy fashioned would have profound impact on King’s moral and ethical vision. They linked the vision of Jesus Christ as stated in the Bible of bringing good news to the poor, recovery of sight to the blind and proclaiming liberty to the captives, with the Hebrew prophet’s mandate of speaking truth to power.

Similar to how they responded to the complex challenges brought on by the Great Migration of the early 20th century, King brought prophetic interpretation to brutal racism, Jim Crow segregation and poverty in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Indeed, King’s prophetic vision ultimately invited his martyrdom. But through the prophetic preaching tradition already well established by his time, King brought people of every tribe, class and creed closer toward forming “God’s beloved community” – an anchor of love and hope for humankind.

This is an updated version of a piece first published on Jan. 15, 2017.

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter. ]

Editor’s note: This piece has been corrected to state that President Woodrow Wilson declared entrance into World War I in 1917.![]()

Kenyatta R. Gilbert, Professor of Homiletics, Howard University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

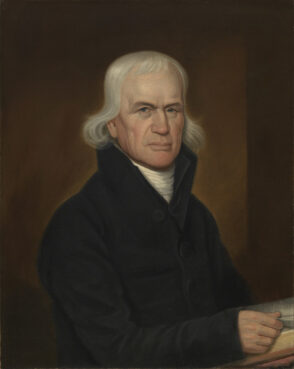

(RNS) — Two and a half centuries ago, Francis Asbury arrived in the United States from Great Britain, bringing with him what would become the Methodist faith. He went on to spread it across the country, with St. George’s Church in Philadelphia as his home base.

St. George’s will mark the occasion of Asbury’s arrival with a weekend of events at the end of October. But the historic church, which remains the oldest continually used Methodist building in the United States, is also the starting point of three African American churches and one denomination after a “walkout” by Black worshippers.

Over time, recounts the Rev. Mark Salvacion, St. George’s current pastor, African Americans —some recently freed from slavery — were segregated to the sides of the church, to the back of the building and to a balcony, preventing them from receiving Communion on the church’s main floor.

Salvacion describes this and other parts of St. George’s history in the church’s “Time Traveler” program for teen confirmation students learning about their faith and in classes of middle-age adults training to become certified lay ministers.

Teenage confirmation students attend a “Time Traveler” program at Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia in 2018. Photo courtesy of HSG

“It’s not just telling happy stories about Francis Asbury itinerating to West Virginia,” said Salvacion, pastor of what is now called Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church. “It’s uncomfortable stories about race and the meaning of race in the United Methodist Church.”

The turning point for many African American worshippers, already dissatisfied with mistreatment, was a Sunday morning in the late 1700s. Lay preacher Richard Allen saw another Black church leader, Absalom Jones, forcibly pulled up while praying on his knees at St. George’s.

That led Allen and some of the other Black attendees to leave what was then known as St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church and strike out on their own — in different ways.

Portraits of Absalom Jones, from left, Harry Hosier and Richard Allen in Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church museum in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of HSG

“This raised a great excitement and inquiry among the citizens, in so much that I believe they were ashamed of their conduct,” wrote Richard Allen in his autobiography. “But my dear Lord was with us, and we were filled with fresh vigour to get a house erected to worship God in.”

In 1791, Allen, who had been a popular preacher at St George’s 5 a.m. service, started what is now Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Asbury dedicated its first building, a former blacksmith shop, in 1794.

“Here’s Asbury and he comes in and he still has this kind of relationship with Richard Allen that is more than just collegial,” the Rev. Mark Tyler, current pastor of Mother Bethel, said of the men who were the first bishops of the Methodist and AME churches, respectively.

“I mean, you go out of your way as the representative and the saint of Methodism in America and you dedicate Mother Bethel. That is a statement that you’re behind this and endorsing it.”

Bronze statue of Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, on the property of Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia on July 6, 2016. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

In 1816, after winning a court battle for its independence from the Methodist Episcopal Church, Allen started the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the nation’s first Black denomination.

Jones went on to serve as a lay leader of the African Church that began in 1792. Two years later, the congregation became affiliated with the Episcopal Church and was renamed the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. Jones was ordained a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802.

Arthur Sudler, director of the Historical Society & Archives at the 1,000-member church, said the 250th anniversary of Asbury’s U.S. arrival is significant not only for the three Philadelphia congregations that began after discord with St. George’s but also for the city and the three denominations they now represent.

“It’s an epochal moment simply because Francis Asbury’s role in helping develop Methodism in America, in part through his participation there at St. George’s, is one of those factors that gave birth to the Black Christian experience in Philadelphia,” he said. “And in America more broadly, because of the seminal role of Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, and Harry Hosier and their connections between what became these three denominations, the AME Church, the United Methodist Church and the Episcopal Church.”

Service at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in 2019. Photo by Dale Williams for D’Zighner Studios

Hosier initially stayed at St. George’s with other Black attenders who did not leave with Jones and Allen. He also was a closer colleague to Asbury than the other two men, having been a traveling companion who preached with the Methodist leader across the South. Allen, a free man, had declined the offer, avoiding a risky return to the region of the country where slavery remained legal.

Hosier helped found another Philadelphia Methodist congregation, which initially met in people’s homes and eventually became known as Mother African Zoar United Methodist Church. Asbury dedicated its building in 1796 and preached there a number of times, according to the United Methodist Church’s General Commission on Archives and History.

After it celebrated its 225th anniversary, Mother Zoar retained its name but merged with New Vision United Methodist Church in north Philadelphia, with a current average of 75 people at in-person worship services. It thus remains the oldest Black congregation in the United Methodist tradition in continuous existence.

Portrait of Francis Asbury in 1813 by John Paradise. Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery/Creative Commons

Given the steps of Allen and Jones, why did Hosier and other Black worshippers who once prayed at St. George’s remain within the Methodist Church?

“That is a million-dollar question,” said the Rev. William Brawner, the part-time pastor of Mother Zoar.

He said he assumes “those who left with Absalom, those who left with Richard were tired and figured that they could not change the system of injustice from the inside.” The founders of Zoar chose a different approach, hoping that remaining Methodist would help “change the hearts and minds of the people that were literally oppressing them.”

All these years later, Brawner said he does not judge the different decisions made by African American worshippers at St. George’s, who were unable to freely use spiritual practices that were different from those of white congregants and reflected beliefs some had brought with them from Africa.

“I think people left because of feeling uncomfortable and unaccepted in one place,” he said. “So the split could be celebrated now because of what has become of the split, but people didn’t split out of privilege. People split out of pain. They split because they were hurting.”

The emotions arising from the divisions transcended the centuries.

The Rev. Mark Tyler. Courtesy photo

Tyler, whose church has more than 700 members today, recalled the 2009 service when congregants of Mother Bethel worshipped at St. George’s for what was believed to be the first joint Sunday morning service since the 1700s. As the preacher for that day, he said the gathering was a “cathartic moment,” prompting many of his church’s members to weep.

Salvacion and the clergy of the other churches say occasional joint gatherings have continued since then, such as some of the congregations sharing Easter sunrise services and the annual Episcopal Church observance honoring Absalom Jones.

St. George’s currently has about 15-20 worshippers and a membership of about 50. It expects dozens of United Methodists and invited guests from other churches to attend the Oct. 30-31 commemoration.

Its pastor also expects exchanges and shared events will continue in the future among the congregations whose first members left his church building.

“We all view this history as being common history that we share,” said Salvacion, an Asian man who is one of St. George’s first pastors of color.

Interior of Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative Commons

Tyler said the ongoing connections between St. George’s and Mother Bethel probably weren’t envisioned by anyone two centuries ago.

“The current relationship of these two congregations is, in some ways, a sign of hope for what’s possible,” he said. “If it can happen in these two congregations maybe it’s possible for us as a country and as a world. I have to take it for what it is — just a small sign of hope, in spite of all the kind of guarded optimism that I have.”

Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, holds a one-cent coin from 1817 on Wednesday Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. The coin helped archaeologists confirm that a recently unearthed brick-and-mortar foundation belonged to one of the oldest Black churches in the United States. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (AP) — The brick foundation of one of the nation’s oldest Black churches has been unearthed at Colonial Williamsburg, a living history museum in Virginia that continues to reckon with its past storytelling about the country’s origins and the role of Black Americans.

The First Baptist Church was formed in 1776 by free and enslaved Black people. They initially met secretly in fields and under trees in defiance of laws that prevented African Americans from congregating.

By 1818, the church had its first building in the former colonial capital. The 16-foot by 20-foot (5-meter by 6-meter) structure was destroyed by a tornado in 1834.

First Baptist’s second structure, built in 1856, stood there for a century. But an expanding Colonial Williamsburg bought the property in 1956 and turned it into a parking lot.

First Baptist Pastor Reginald F. Davis, whose church now stands elsewhere in Williamsburg, said the uncovering of the church’s first home is “a rediscovery of the humanity of a people.”

“This helps to erase the historical and social amnesia that has afflicted this country for so many years,” he said.

Colonial Williamsburg on Thursday announced that it had located the foundation after analyzing layers of soil and artifacts such as a one-cent coin.

For decades, Colonial Williamsburg had ignored the stories of colonial Black Americans. But in recent years, the museum has placed a growing emphasis on African-American history, while trying to attract more Black visitors.

Reginald F. Davis, from left, pastor of First Baptist Church in Williamsburg, Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist, and Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, stand at the brick-and-mortar foundation of one the oldest Black churches in the U.S. on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. Colonial Williamsburg announced Thursday Oct. 7, that the foundation had been unearthed by archeologists. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

The museum tells the story of Virginia’s 18th century capital and includes more than 400 restored or reconstructed buildings. More than half of the 2,000 people who lived in Williamsburg in the late 18th century were Black — and many were enslaved.

Sharing stories of residents of color is a relatively new phenomenon at Colonial Williamsburg. It wasn’t until 1979 when the museum began telling Black stories, and not until 2002 that it launched its American Indian Initiative.

First Baptist has been at the center of an initiative to reintroduce African Americans to the museum. For instance, Colonial Williamsburg’s historic conservation experts repaired the church’s long-silenced bell several years ago.

Congregants and museum archeologists are now plotting a way forward together on how best to excavate the site and to tell First Baptist’s story. The relationship is starkly different from the one in the mid-20th Century.

“Imagine being a child going to this church, and riding by and seeing a parking lot … where possibly people you knew and loved are buried,” said Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist. She is also board president of the Let Freedom Ring Foundation, which is aimed at preserving the church’s history.

Colonial Williamsburg had paid for the property where the church had sat until the mid-1950s, and covered the costs of First Baptist building a new church. But the museum failed to tell its story despite its rich colonial history.

“It’s a healing process … to see it being uncovered,” Harshaw said. “And the community has really come together around this. And I’m talking Black and white.”

The excavation began last year. So far, 25 graves have been located based on the discoloration of the soil in areas where a plot was dug, according to Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology.

Gary said some congregants have already expressed an interest in analyzing bones to get a better idea of the lives of the deceased and to discover familial connections. He said some graves appear to predate the building of the second church.

It’s unclear exactly when First Baptist’s first church was built. Some researchers have said it may already have been standing when it was offered to the congregation by Jesse Cole, a white man who owned the property at the time.

First Baptist is mentioned in tax records from 1818 for an adjacent property.

Gary said the original foundation was confirmed by analyzing layers of soil and artifacts found in them. They included an one-cent coin from 1817 and copper pins that held together clothing in the early 18th century.

Colonial Williamsburg and the congregation want to eventually reconstruct the church.

“We want to make sure that we’re telling the story in a way that’s appropriate and accurate — and that they approve of the way we’re telling that history,” Gary said.

Jody Lynn Allen, a history professor at the nearby College of William & Mary, said the excavation is part of a larger reckoning on race and slavery at historic sites across the world.

“It’s not that all of a sudden, magically, these primary sources are appearing,” Allen said. “They’ve been in the archives or in people’s basements or attics. But they weren’t seen as valuable.”

Allen, who is on the board of First Baptist’s Let Freedom Ring Foundation, said physical evidence like a church foundation can help people connect more strongly to the past.

“The fact that the church still exists — that it’s still thriving — that story needs to be told,” Allen said. “People need to understand that there was a great resilience in the African American community.”

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in 2016. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

(RNS) — A century and a half ago, nine young men and women embarked on a trip from Fisk University, establishing a tradition of singing spirituals that both funded their Nashville, Tennessee, school and introduced the musical genre to the world.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, based at the historically Black university founded by the abolitionist American Missionary Association and later tied to the United Church of Christ, started traveling 150 years ago on Oct. 6, 1871. They since have continued to sing so-called slave songs such as “Down by the Riverside” and “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and stood on stages from New York’s Carnegie Hall to Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium.

Musical director Paul Kwami has led the group since 1994 and sang with it when he was a Fisk student in the 1980s. Then and now he views the songs as not only expressions of the religious beliefs of enslaved people, but also of the original singers and the ones who continue to sing today.

“There are songs like ‘Ain’t-a That Good News,’ which is a song that talks about having a crown in heaven, having a robe in heaven,” said Kwami, a member of a nondenominational Full Gospel church in Nashville. “Well, they’ve never been to heaven, but then they’re singing about heaven — that’s an expression of faith.”

Kwami, a native of Ghana, in West Africa, talked with Religion News Service about how the ensemble began, who should sing spirituals and which of the songs are his favorites.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in Jubilee Hall at Fisk University on Oct. 29, 2020. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers won their first Grammy in 2020 for an album that celebrates almost a century and a half of music. What does that say about the endurance of the group and the music that they have sung for so long?

The album was actually produced on the (university’s) 150th anniversary. But then, of course, it is the Fisk Jubilee Singers who won the Grammy, which actually makes me realize that people still recognize who the Fisk Jubilee Singers are. And people still appreciate the music. Additionally, people realize Fisk Jubilee Singers are artists and do not limit themselves to just Negro spirituals. There’s versatility in our choice of music when we have celebrations.

How do you define spirituals, and differentiate them from other forms of African American music sung in Black churches and beyond?

The Negro spirituals are songs that were created by the slaves during their time of slavery. But when we talk about music like jazz or blues or gospel, those genres of music came long after the Negro spirituals were established. And some people even say these other forms of music were birthed out of the Negro spirituals.

When we talk about the Negro spiritual and, say, gospel music, the performance styles are completely different. Gospel music simply deals with church music with a lot of instrumental accompaniment, clapping, a lot of improvisation. But with the Negro spiritual, even though there may be some improvisation, it doesn’t involve a lot of improvisation. Traditionally, Negro spirituals don’t call for instrumental accompaniment.

When the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing, the music is a cappella. The original Fisk Jubilee Singers transformed the Negro spiritual into an art form or concert spiritual. And because of that, clapping, for example, is not recognized as part of a performance of Negro spirituals.

Spirituals are known for their layers of meaning, some of which were hidden to slave masters. Can you give an example of one that is often sung by Fisk Jubilee Singers that reflects that?

One we often sing is “Steal Away to Jesus.” (One) meaning is that we will run away to the North — because we’re stealing away to Jesus — and Jesus was referring to a place of freedom.

When George White, a music professor and Fisk’s treasurer, decided to have singers from the school perform the spirituals for white audiences as fundraisers, was his idea supported by many or was it controversial or both?

To leave Fisk with a group of students to go on a tour, singing to raise money — that was opposed. The administration at Fisk at that time did not believe he would succeed. They thought this was more of an experimental adventure because no one had ever done that. He was not sure of how audiences would receive Black young people singing so he taught them to sing Western (and European) classical music with a hope that would be more attractive to the various audiences. The Fisk Jubilee Singers were also not willing to sing the Negro spirituals because those songs were very sacred to them. But eventually, they started singing the Negro spirituals to the delight of their audiences.

The spirituals were “concertized” for performance for these fundraisers. Do you think anything was lost as the songs moved from the field where slaves had labored to concert halls where people paid to hear them sung?

I don’t think anything was lost. I read a quote by one of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers, and in this book he transcribes some of the songs they sang. I look at the melodies and they’re the same melodies we sing except the arrangements may be different.

How were the singers received at a time when slavery had just ended and African Americans were not welcome in many venues that were segregated?

Originally, they were not well received. There are accounts where people would go into the concerts, listen to the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing and not even give donations. There are accounts of Fisk Jubilee Singers going into hotels and hotel owners, realizing they were Black people, turned them away, wouldn’t give them a place to sleep or food to eat. There was a time when George White was able to purchase first-class coach (train) tickets for them but they were refused admittance into the first-class coaches because of the color of their skin. There is a painting somewhere that someone depicted them looking more like animals on stage singing. So they did go through those types of experiences as they went on their first tour. But I always say the young Fisk students who went out to raise funds for the university kept their focus on their mission and also were able to sing their songs and win the hearts of many people.

There have been debates over whether white people singing spirituals is a form of cultural appropriation. And I wonder where you stand on that issue.

As a musician I don’t agree with that because growing up in Ghana, we were taught songs like the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s “Messiah.” The performance of music, I don’t believe should be limited to one specific culture. Because music, rather, brings people together. I would rather encourage people of every culture to learn music of other cultures.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers sang with The Erwins, a Southern gospel group, in February, including the song ” Watch and See.” How often do the Fisk singers sing music other than spirituals and is that generally well received, or are they criticized for not sticking with the music tradition for which they’re known?

I think one of the reasons we won the Grammy is because we sang with other people and the album consists of a variety of music that actually would not be classified as Negro spirituals. The album consisted of country music. We had some blues. We had gospel. We do want to be remembered as an ensemble that sings Negro spirituals but when there are occasions that call for us to sing other types of music and if it fits into our schedule, we are going to do so.

Do you have a favorite spiritual sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers and, if so, which one and why?

I have a lot of favorite spirituals. One of them is ” Lord, I’m Out Here on Your Word.” I like that spiritual because it’s a song that helps me to be committed to my work. A line in the song says “If I die on the battlefield, Lord, I’m out here on your Word.” That is telling me that no matter what goes on, I am out to serve God. And I know he is a faithful God. And I have to be faithful to him as well. If I’m serving him, then no matter what’s going on, I trust him to provide whatever I need to succeed in my work.

Another is “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” I love that song, again, because it gives me the idea that God takes care of us.