Thanksgiving hymns are a few centuries old, tops – but biblical psalms of gratitude and praise go back thousands of years

Thanksgiving doesn’t ring in the ear for months on end, unlike another holiday that lies just ahead. Yet readers may remember a couple of hymns that roll around each November in church, around the dinner table, or even – for readers of a certain age – in school. One I remember well is “Come, Ye Thankful People, Come.” Then there’s “We Gather Together,” or “We Plough the Fields and Scatter.”

Interestingly, for songs associated with a distinctly American holiday, none have American origins. “Come, Ye Thankful People” was written by Henry Alford, a 19th-century English cleric who ascended to become dean of Canterbury Cathedral and supposedly rose to his feet to give thanks after every meal and at the close of every day. “We Gather Together” is much older, written in 1597 to celebrate the Dutch victory over the Spanish in the Battle of Turnhout. “We Plough the Fields” was written by a German Lutheran in 1782.

As someone who studies American culture and religious music, I’m interested in the backstory of the songs that we have come to take for granted. Someone wandering into a church and picking up a hymnal will likely find a handful of hymns filed under “thanksgiving,” but many more express a general sense of gratitude, such as “Now Thank We All Our God” and “For the Beauty of the Earth.” Even more hymns fall under the related category of praise – after all, a common response to feeling blessed or rescued is to offer praise to the higher being thought to bestow those gifts.

None of these impulses are uniquely Christian, or even religious. But hymns of praise and gratitude have been central to Jewish and Christian worship for millennia. In fact, they go back to one of the best-known scenes in the Hebrew Bible.

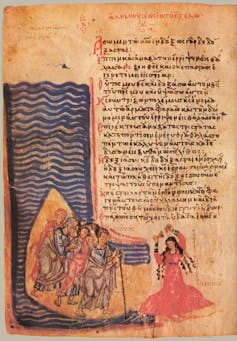

Fleeing Pharaoh

The earliest musical performance mentioned in the Hebrew Bible is “The Song of the Sea,” referring to two songs Moses and his sister Miriam sing to celebrate the Israelites’ escape from Egypt. As Pharaoh’s army pursues the fleeing slaves to the edge of the Red Sea, God opens a dry path for them before closing up the sea to swallow the soldiers, according to the Book of Exodus:

Then Miriam the prophet, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women followed her, with timbrels and dancing. Miriam sang to them: ‘Sing to the Lord, for he is highly exalted. Both horse and driver he has hurled into the sea.’

Jewish singer Debbie Friedman, who died in 2011, wrote “Miriam’s Song,” adapting these lines from Exodus into a modern favorite.

Temple worship

One research project took me deep into the world of the Hebrew Psalms, which originally were sung mainly during rituals at the temple in Jerusalem. Scholars have speculated for centuries over the composition and sequencing of these Hebrew poems that form one book of the Bible. The 150 psalms include a great many laments, expressions of praise and gratitude, and quite a few texts that combine both.

Hermann Gunkel, a pioneering Bible scholar at the turn of the 20th century, developed a system of classifying the texts in the Book of Psalms by genre, which experts still use today. What Gunkel called “Thanksgiving” psalms are texts that celebrate God’s actions to bestow blessings and alleviate affliction in particular times and places: healing from a serious illness, for example. Gunkel’s categories also include psalms that refer to gratitude for more general divine actions: creating the cosmos and the wonders of the natural world, or protecting the ancient Israelites from foreign enemies.

It’s hard to find a text more brimming with gratitude than Psalm 65, which includes verses very suitable for Thanksgiving Day:

The streams of God are filled with water

to provide the people with grain,

for so you have ordained it.

You drench its furrows and level its ridges;

you soften it with showers and bless its crops.

You crown the year with your bounty,

and your carts overflow with abundance.

A new idea: Songs about Jesus

Though the original tunes of the psalms have been long lost, their words are still a mainstay of religious singing for both Jews and Christians.

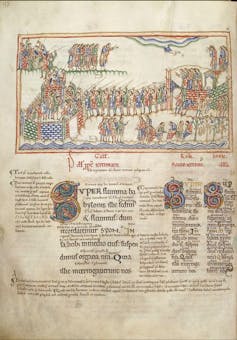

Their key role in Protestant churches today owes partly to the Reformation of the 16th century. During the Renaissance, Catholics had developed more ornate musical forms for the Mass, including the use of polyphony: songs with two or more simultaneous interwoven melodies. Protestants, on the other hand, decided that unadorned psalms, put into standard musical meters that matched existing tunes, were optimal for church.

Reformation leader Martin Luther loved music and wrote his own hymns with original words that are still popular today, such as “A Mighty Fortress is Our God.” As far as the more austere reformer John Calvin was concerned, however, the plainer the better. Unharmonized a cappella psalm singing was plenty good for the sabbath, he insisted.

Calvin’s judgment carried the day in New England, which was settled largely by Puritan Calvinists. In fact, the first book published in North America was “The Bay Psalm Book,” in 1640. It took a century for hymns with new words to start finding acceptance in churches, and even longer for organs to make an appearance there.

Gradually these restrictions began to soften, even in New England. During the 1700s, hymns began to compete with psalms in popularity. The key innovator was Isaac Watts, a talented poet who wondered why Christians couldn’t sing worship songs that referenced Jesus Christ – since the Book of Psalms, written before his birth, did not. John and Charles Wesley, founders of Methodism, were also inveterate hymn writers.

Praise yesterday and today

To modern ears, the difference between psalms and hymns is barely perceptible. Hymns often draw heavily on the images and tropes of the psalms. Even a simple-sounding Thanksgiving hymn like “We Gather Together” contains no fewer than 11 allusions to particular psalms.

Watts, the Wesley brothers and several other hymn writers were part of movements that helped birth modern evangelical Christianity. Some of the most famous hymns of thanksgiving and praise have been popularized by evangelical revivals over the centuries: “Amazing Grace,” by an 18th-century English curate, and “How Great Thou Art,” the theme song of world-famous preacher Billy Graham’s revivals.

Over the past 30 years, the booming genre of contemporary worship music, often referred to simply as praise music, has become the standard heard in megachurches and other evangelical congregations across the world. Not surprisingly, praise and gratitude are inescapable themes in this genre – whether or not they evoke a Thanksgiving feast.![]()

David W. Stowe, Professor of Religious Studies, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.