by Doreen Ajiambo, RNS | May 13, 2019 | Headline News |

People browse the eVitabu app on a tablet provided by African Pastors Fellowship. Video screenshot via African Pastors Fellowship

KAMPALA, Uganda (RNS) — On a recent Sunday morning, dozens of South Sudanese refugees gathered inside a tent at Imvepi Refugee Camp to thank God for enabling them to found a new church.

The new Pentecostal church was partly made possible by a new app that links preachers to Bible translations and theological resources from which they can prepare sermons and teach congregants about their faith.

“It’s a new dawn for refugees,” said Pastor Chol Mayak, 48, a father of four who recently attended a training on the app. “We are going to train other refugees so that they can open more churches and spread the gospel across the camps.”

by Doreen Ajiambo, RNS | Nov 7, 2018 | Headline News |

A nun reflects during a solemn moment as Pope Francis leads a Holy Mass for the Martyrs of Uganda at the area of the Catholic Sanctuary in the Namugongo area of Kampala, Uganda, on Nov. 28, 2015. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

KAMPALA, Uganda (RNS) — Thousands of Catholics in one of the world’s poorest nations are objecting after the church asked the government to collect a 10 percent tithe from worshippers on its behalf.

A similar “church tax” in Germany has generated record revenue for the Catholic Church there, according to the German Handelsblatt newspaper — but the policy is also blamed for driving millions of people to leave the faith.

“Why should the church keep asking for money all the time?” asked John Mayanja, 46, a teacher at Kitante Primary School in the East African nation. “We are supposed to give tithe willfully and without any threats from our church leaders.”

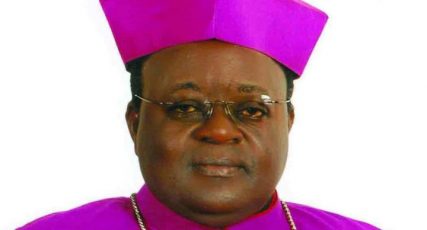

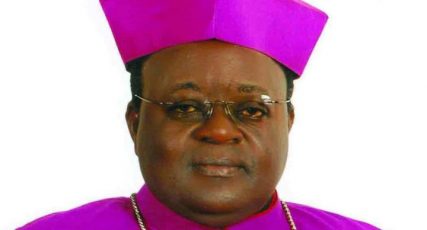

During an Oct. 28 Mass at Rubaga Cathedral in the capital city of Kampala, Archbishop Cyprian Kizito Lwanga urged the Ugandan government to immediately begin deducting a 10 percent tithe from the monthly salaries of all Catholic believers to ensure the church’s work does not stop because of lack of funds.

Archbishop Cyprian Kizito Lwanga. Photo courtesy of Archdiocese of Kampala

Lwanga said many do not voluntarily give the church 10 percent of their incomes.

“We lie to God that we pay church tithe off our monthly salaries. But during a Mass like this, whenever we ask for tithe, everyone gives only what they have at that time,” Lwanga said.

“The Bible says a tenth of whatever you earn belongs to the church, and you should give me support as I front this proposal because it is good for us.”

Some Ugandan Christians questioned the church’s motives, saying a church tax forces poor people to fund extravagant lifestyles for some priests and bishops.

“They should understand that we are paying fees for our children and servicing government loans. We have no money,” Mayanja said.

More than a third of Uganda’s nearly 43 million people live on less than $1.90 per day, the international marker of extreme poverty, according to World Bank. The Brookings Institution reports 3 in 10 households in Uganda spend more than 65 percent of their income on food.

Lwanga said he wants Catholics in Uganda to emulate their counterparts in Germany, where 8-9 percent of churchgoers’ income is deducted and channeled to the respective faiths.

“The money is used to build and renovate their churches,” said Lwanga, who also serves as chairperson of the ecumenical Uganda Joint Christian Council. “If an employee in Germany gets $10,000, the government deducts $1,000 and gives it to the church, and it is working very well.”

The Catholic Church in Germany collected a record $7.1 billion last year in taxes, Handelsblatt reported, although more than 2.2 million Germans have formally deregistered from the church since 2000. Those who deregister are no longer subject to the church tax but can no longer participate in church life — an outcome Archbishop Georg Gänswein has called a “serious problem.”

Several other European nations also collect religious taxes, which are sometimes voluntary, according to the Pew Research Center.

Catholic faithful pray in front of a cross of Jesus Christ erected by a roadside in Kakoge, north of Uganda’s capital Kampala, on October 18, 2015. Photo by James Akena/Reuters

The idea of deducting tithes from salaries was widely supported by some Ugandan officials who are also Catholic believers. Many dismissed the archbishop’s critics, saying Lwanga’s suggestions were based on Scripture.

“The archbishop was reminding the church and only Catholics that they need the money to run church activities,” said Betty Nambooze, a legislator representing Mukono, a town in central Uganda.

Catholics are Uganda’s largest religious group, but the Catholic share of the population has declined slightly in recent years. Catholics made up 39.3 percent of the population in the 2014 census, down from 41.6 percent in 2002. Around 32 percent of Ugandans are Anglican, and 14 percent are Muslim.

Religious leaders from other denominations questioned Lwanga’s strategy.

“Any believer who is not paying his or her tithe has no space in heaven. They are stealing and cheating God,” said Pastor Moses Mugisa of Redeemed Church of God, a Pentecostal church. “So there’s no need of forcing believers to pay tithe through government.”

Some vowed not to support the idea, saying the Bible does not sanction governments to collect tithes and offerings from worshippers.

“I want to ask the government to revoke credentials of any priest or bishop that petitions it to help them collect tithe,” Cyrus Rod, a bishop at Dominion Temple International, a Pentecostal church, told journalists in Kampala. “The clergy are working purely for material reward and we’ll not allow them to mislead the country. The role of priests is to collect tithes and offerings. It’s a not a political role.”

Mayanja and other Catholics said they will oppose Lwanga’s proposal because they believe it goes against Catholic teaching.

“God does not demand a certain amount of money from his people,” said Mayanja. “We give offering and tithe from our hearts. What our leaders are doing is extortion and is not based on the word of God.”

Uganda, in red, located in eastern Africa. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

by Doreen Ajiambo, RNS | Oct 18, 2018 | Headline News |

JUBA, South Sudan — During a recent Sunday service, Pastor Jok Chol led the congregation at his Pentecostal church to pray for a sustainable peace after President Salva Kiir and rebel leader Riek Machar signed the latest peace agreement in neighboring Sudan.

The two leaders signed an agreement in mid-September, hoping to end years of conflict.

“I want to rebuke the spirits of confusion in our leaders,” Chol prayed, amid cheers of “Amen” from hundreds of worshippers. “We thank God and pray that he touches the hearts of our leaders so that they can embrace the new peace agreement.”

During his sermon, Chol urged his congregants to have faith and hope and continue to pray for a sustainable peace. He said they should refuse to be divided by political leaders along ethnic lines.

“We are all children of God,” said Chol, 55, a father of three. “We should treat each other with the love of Jesus Christ. Please don’t do anything wrong because your leader has told you. Follow what the Bible says and you will be blessed.”

Chol and his congregants are among thousands of Southern Sudanese gathering in churches and various mosques across major cities and refugee camps to pray for their country, which has been embroiled in civil war since 2013.

South Sudan, red, in central Africa. Map courtesy of Creative Commons

South Sudan erupted into civil war after a power struggle ensued between Kiir and Machar. The conflict spread along ethnic lines, killing tens of thousands of people and displacing millions of others internally and outside the border. The economy has collapsed as a result of the ongoing war. Half of the remaining population of 12 million faces food shortages.

The latest treaty is the second attempt for this young nation to find peace. South Sudan became officially independent from Sudan in 2011. In 2013, civil war broke out after Kiir fired Machar as his deputy, leading to clashes between supporters of the two leaders.

A previous peace deal in 2016 tried to bring warring sides together so they could find a permanent solution. But fighting broke out in the capital city of Juba a few months later when Machar had returned from exile to become Kiir’s vice president as outlined in the peace agreement.

Under the new power-sharing arrangement Machar will once again be Kiir’s vice president.

Religious leaders such as Chol are optimistic that the latest peace agreement will hold up. They believe it is an answered prayer for thousands of faithful.

“I have hope in the new peace agreement,” said Bishop Emmanuel Murye of Episcopal Church in South Sudan. “We have been praying for peace to return to the country and we are happy that our leaders are committed to bring peace.”

Murye has been holding evangelistic meetings in refugee camps in Uganda, where more than 1 million South Sudanese have taken refuge. He said people in the camps have been praying for leaders to embrace the new deal.

“People want to come back home,” he said. “They are tired of staying in the camp. Life in the camp is not easy because there is no food to eat and children are not going to school. They have been praying for peace and they believe this is an answered prayer.”

But others still doubt the new peace deal.

South Sudan’s president, Salva Kiir, center, and opposition leader Riek Machar, right, shake hands during peace talks at a hotel in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on June 21, 2018. The two leaders signed an agreement in mid-September. (AP Photo/Mulugeta Ayene)

Fighting broke out in the country, killing 18 civilians, two days after the warring sides signed the latest agreement to end the civil war. Kiir and Machar supporters blamed each other for the attacks.

Religion has played a major role in South Sudan’s conflicts.

According to a recent report by Pew Research Center, Christians make up about 60 percent of the population of South Sudan, followed by 33 percent who are followers of African traditional religions. Six percent are Muslim.

The war for South Sudanese independence was often framed in religious terms — pitting Christians and followers of traditional religions against the Muslim leaders of Sudan.

Achol Garang, a catechist at the Bidi Bidi refugee camp in northern Uganda, said God was punishing her country for its sins. She said political leaders in South Sudan used religion as a tool to fight for independence from Sudan.

“They called themselves Christian liberators when they were fighting and promised to take us to the promised land of self-government,” said Garang, 45, a mother of five who fled Yei town in southwest South Sudan in 2015. “They lied to God and that’s the reason we are suffering now. We should just continue to pray for forgiveness of sins. We will get the answer one day.”

The South Sudanese government has accused church leaders of promoting violence among congregants by dividing them along ethnic lines.

The East Africa nation has two major tribes that have been involved in the civil war. People from Dinka tribe are loyal to Kiir, while people from Nuer tribe are led by Machar.

Religious leaders agree there has been ethnic conflict. But they say the church still remains strong.

“While individual clergy may have their own political sympathies, and while pastors on the ground continue to empathize with their local flock, the churches as bodies have remained united in calling and for an end to the killing, a peaceful resolution through dialogue, peace and reconciliation — in some cases at great personal risk,” John Ashworth, who has advised Catholic bishops and other church leaders in South Sudan, told Inter Press Service in Juba.

Chol, the Pentecostal pastor, believes the country has now found new peace after prayers.

“We must have faith that we have already found peace,” he said. “God has promised that he will never abandon his children, and we are happy he has answered our prayers.”

by Doreen Ajiambo, RNS | Oct 1, 2018 | Headline News |

Youth and young men live, beg and use drugs on the streets of Kampala, Uganda, on May 2, 2018. Drug abuse is prevalent in the homeless street community. RNS photo by Doreen Ajiambo

KAMPALA, Uganda — As dawn breaks in this bustling capital city of 1.5 million people, Pastor Moses Mugisa treks along a main road, carrying his Bible as he heads to the streets to meet young people abusing drugs.

In the Wakiso district near the capital, youths meet in various dens to smoke marijuana and shisha and to drink illicit alcohol. Along the street corners of other slums, young men and women gather in abandoned buildings and rubbish dumps.

“These young people smoke and sniff everything,” said Mugisa, 52. “The drugs turn them into near-zombies. But we are helping them to recover from the abuse.”

Mugisa, who ministers at Redeemed Church of God in Wakiso, said he was also a drug addict before he was saved by God. He is now giving moral support to people with substance abuse issues, trying to rehabilitate them and ensure they are as healthy as possible under the tough circumstances.

“I talk to them about my past experience and also encourage them to stop abusing drugs and go to rehab,” he said, reflecting on his past life. “We pray together because I understand this is more of spiritual healing than physical.”

Drug and alcohol abuse in this East African nation has affected thousands. Uganda has one of the highest per-capita rates of alcohol consumption in sub-Saharan Africa, and 9.8 percent of adults have an alcohol-use-related disorder, according to recent studies cited by the National Institutes of Health. A study of 12- to 24-year-olds in northern and central Uganda showed 70 percent had used substances of abuse and more than a third used them regularly.

Uganda, in red, located in eastern Africa. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

The situation has prompted faith leaders in the country to intervene, with many urging the government to partner with the church to combat drug abuse among youths.

The Rev. Robert Muhiirwa of Fort Portal Catholic Diocese in Kampala recently said the church is battling drug abuse among youths, but he advised the government to partner with church-allied organizations or foundations to create awareness and treat addicts.

“It’s more worrying that we have lost many lives and resourceful professionals because of alcohol and drugs,” he said when he visited a rehabilitation center allied to the Catholic Church at Wakiso this month. The center serves at least 1,200 youths. “I urge the government to partner with us so that we can create awareness among our youths.”

In 2016, Ugandan lawmakers proposed new regulations on alcohol sales, including limits on bars’ opening hours. The measure has not passed, although Uganda does plan next year to ban the sale of sachet alcohol, sold in small plastic pouches.

Meanwhile, many addicts in Kampala and other cities across the country still walk the streets and alleys, scavenging for anything they can turn into cash and begging for meals.

Frank Mutebi, 21, said he didn’t know what he was getting into when he started using drugs and he wishes he had never tried them.

“I don’t know why I’m here,” he said, referring to his life on the streets. “I feel very high when I’m drinking alcohol and smoking bhang. It makes me complete and I can think properly like others. But it’s not something I like.”

Mutebi now wants to go to rehab but he said it was expensive for his parents.

A Ugandan youth begs on the streets of Nairobi, Kenya, on Jan. 10, 2018. He came to Kenya in 2013 seeking work, but he ended up on the streets due to drug abuse. RNS photo by Doreen Ajiambo

Dr. David Basangwa, a psychiatrist in Kampala, said the rate of youths abusing drugs, especially illicit alcohol, is alarming. Most of the youths seeking treatment at his center are drug addicts who are warned of serious effects, he said.

“Abusing drugs of any kind can result in death from suffocation caused by the chemical entering the lungs and the central nervous system,” he said. “Youths should desist from taking alcohol and other drug abuse because it risks their lives.”

Meanwhile, Mugisa, the church pastor, said he will continue to save lives of drug addicts, but he urged the government to make treatment free for anyone willing to go to a rehab center.

“The problem is money,” he said. “Many youths are willing to go to rehab but they are told to pay for the services. It’s very expensive for their parents. I want to urge the government to make it free so that we can save many lives on the streets.”

by Doreen Ajiambo, RNS | Sep 27, 2018 | Headline News |

A preacher delivers the sermon with sign language during a service at Immanuel Church for the Deaf in Dar es Salaam. Video screenshot

BAGAMOYO, Tanzania — On a recent Sunday morning, Isaac Mbaga met with two friends to worship in his house in this town on the east side of the country’s major port city, Dar es Salaam.

As they began their worship service with songs, the three — all of whom are deaf — danced and signed along to the songs.

Soon, they sat and opened their Bibles and read from the Gospel of Matthew: “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.”

Then, Mbaga asked his fellow worshippers in sign language about the meaning of the Scripture. They looked at each other and replied that they did not understand the scriptural message.

“This is the problem we have as deaf people,” said Mbaga, 33, with the help of a sign language interpreter. “We desire to know the Word of God, but we have nobody to help us. We have no pastors and churches around here for deaf people.”

Mbaga and his colleagues are among many deaf Tanzanians who have few options for worship. They say there is only one church nearby where deaf people can worship through sign language interpreters.

Many others across the country who cannot make their way to the church are left to read the Bible on their own to meet their spiritual needs.

Tanzania, in red, located in eastern Africa. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

“These deaf people are very frustrated because they can’t find anywhere to worship God,” said evangelist Mary Temba, who is also deaf. “We have very few churches in the country where deaf people can go and worship. We have only one church in Dar es Salaam, and you need to travel over 300 miles to find another church. In fact, we have only two active churches where deaf people can worship.”

Temba, who oversees several deaf churches in Tanzania and in other East African nations, said churches, mosques and other places of worship in the country are unwelcoming to people with hearing disabilities.

“They really don’t care if deaf people exist in their churches or mosques,” Temba said at her home in Bagamoyo. “These places of worship have no special services for people with hearing disabilities, therefore leaving them out from active worship. This is very unfair.”

Seleman Munisi, who is deaf, has attended the Africa Independent Pentecostal Church at Bago village in Bagamoyo.

Throughout praise and worship time, Munisi danced with other worshippers and often tapped the edge of a folded fist to an open palm to indicate “Amen.”

When the pastor took to the podium to bring the message of the day, Munisi sat attentively but struggled to follow the preaching and prayers.

“I enjoyed the praise and worship service, but I didn’t hear the Word of God,” said Munisi, who is 25. “I love Jesus but I have nowhere I can go and worship. It’s the reason I come here and worship with others. I have no fare to travel to Dar es Salaam and worship with my colleagues with the help of a sign language interpreter.”

The National Bureau of Statistics Disability Survey Report of 2008 showed deafness is Tanzania’s third-most-prevalent form of disability. The number of deaf people was 607,618 in 2008 when the population of the country at the time was 42 million. The population currently stands at 56 million.

The praise team performs at Immanuel Church for the Deaf in Dar es Salaam. Video screenshot

At the Immanuel Church for the Deaf in Dar es Salaam, hundreds of deaf worshippers filled the sanctuary while others stood outside, trying to catch a glimpse through the windows during a recent church service.

The church for the deaf was founded with a group of pastors from Kenya and Uganda when they realized that there was a dire need in Tanzania. The church now has more than 700 congregants.

“We have a problem here but we are going to open more branches. We have realized that the use of sign language has helped deaf people to accept Christ and even live better lives. They are confident and they now feel loved,” said Joseph Hiza, the church’s general secretary.

Church member Agnes Salome agreed. “I’m very happy nowadays because I can worship God,” Salome said through a sign language interpreter. “I can comfortably follow the preaching by the evangelist. The worship service is great and we sing in sign language.”

Others deaf Tanzanians hope to have the same experience in the future.

“We want to worship God like other people because it’s our basic right,” said Mbaga. “I want to feel satisfied with God while I worship.”