by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 6, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

(RNS) — Fannie Lou Hamer was an advocate for African Americans, women and poor people — and for many who were all three.

She lost her sharecropping job and her home when she registered to vote. She suffered physical and sexual assaults when she was taken to jail for her activism. And stories of her struggles reached the floor of the 1964 Democratic Convention — and the nation — when her emotional speech aired on television.

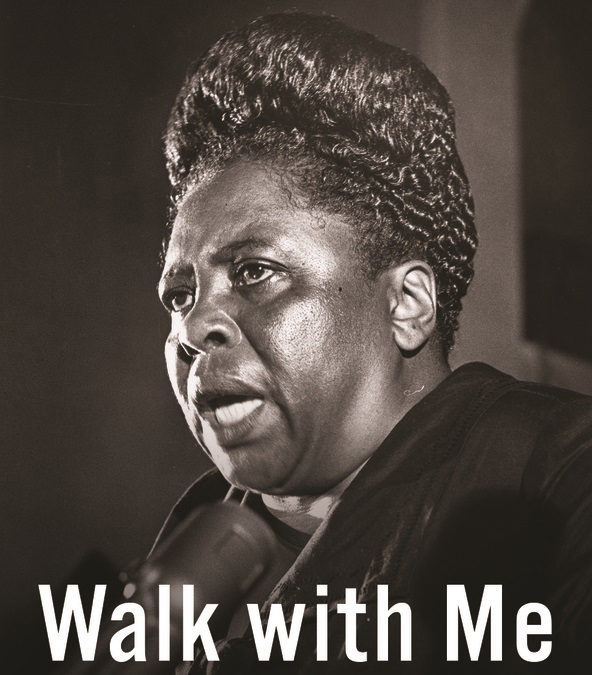

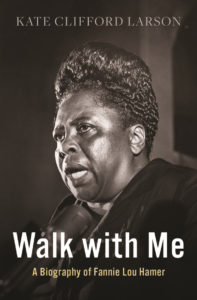

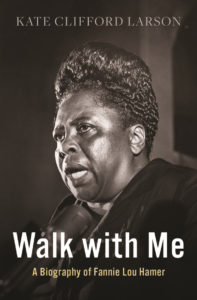

Historian Kate Clifford Larson has written a new book, “Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer,” that reveals details of the faith and life of Hamer, who was born 104 years ago Wednesday (Oct. 6) and died in 1977.

“Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer” by Kate Clifford Larson. Courtesy image

Inspired by young Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers who preached Bible passages about liberation at her church in Ruleville, Mississippi, in 1962, Hamer became a singer and speaker for equal rights and human rights.

“She crawled her way through extraordinarily difficult circumstances to bring her voice to the nation to be heard,” Larson told Religion News Service. “And she knew that she was representing so many people that were not heard.”

Larson spoke to RNS about Hamer’s faith, her favorite spirituals and how music helped the activist and advocate survive.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a biography of Fannie Lou Hamer and how would you describe her as a woman of faith?

I published a book about (Harriet) Tubman and Hamer is so similar to Harriet Tubman, only 100 years later. I decided to start looking into her life and thinking I should do a biography of Hamer. I just became hooked. There were so many similarities, and things I could see in Hamer that I just thought, we need to have a refresher about Fannie Lou Hamer and the strength of her character and how she survived such incredible adversity and found the same kind of solace that Harriet Tubman did — in her faith, in her family and the community — to keep going and fighting and to try to make the world a better place.

It seems she is relatively unknown in many circles despite the credit she’s given by civil rights veterans for her work.

It is curious that she is not well known broadly. And I hope that changes, because I think we need to look back sometimes to see how far we’ve come. And with Hamer, the things that happened to her — she faced the world by confronting that trauma, and that violence, without hate. And the only way she could do that was through her faith, and talking to God and saying: Where are you, what is happening here, give me the strength to carry this weight and to move forward. And she did. She knew hate could really destroy her — that feeling of hating the people that were trying to kill her and subjugate her. She managed to rise above it because she had a greater mission in front of her.

Why did you title the book “Walk With Me”?

The title is from the song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Mississippi, jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her. She asked Euvester to please sing with her because she needed to find strength and she needed God to be with her. So she sang that song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She needed to feel there was something bigger that would help her survive those moments where it wasn’t so clear she would survive. And I found it so powerful that she would do that. She survived that night and was able to get up and walk the next morning.

What other spirituals and gospel songs were particularly important to Hamer as she fought for voting rights and other social justice causes?

One of her favorites is “This Little Light of Mine.” She sang that everywhere, all the time. It’s kind of her anthem. There were some other spirituals, but really, most of the ones she sang a lot during the movement were those crossover folk songs, rooted in Christian spirituals, like “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” She grew up not only in a very strong church environment, the Baptist church, but she grew up in the fields of Mississippi where there were work songs in the fields, call and response songs. Where she grew up was actually the birthplace of the Delta blues music.

She also quoted the Bible to the people she differed with. Were there particular biblical lessons Hamer applied to her fight to help her fellow Black Mississippians?

She used the Bible in many different ways. She used it to shame her white oppressors who claimed also to be Christians, following the path of Christ. She would use the Bible and say: Are you following this path by what you’re doing to me, to my fellow community members and family members? And she used the Bible passages to remind Christian ministers: This is your job, and what are you doing up on that pulpit? You’re telling people to be patient. Well, in the Bible it says stand up and lead people out of Egypt.

You wrote about William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, Hamer’s congregation, throughout the book. What happened there, over the years as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups used it as a place for meetings, classes and rallies?

The church, the ministers participated in the movement and had meetings in that church at great risk to themselves and to the church, and in fact, the church was bombed a couple of times even though the fires were put out, fortunately, very quickly. There were residents in the community that took their lives and put them on the line. They were at great risk, to go to those meetings, to conduct those meetings, to go out and do voter registration drives. It was all centered on the church community because that was really the only community buildings in many of these places where people could meet together to have these discussions.

You said Hamer was at a crossroads as she first listened to those SNCC (pronounced “snick”) activists seeking more people to join their cause.

She experienced trauma, and she had been sterilized against her will — she didn’t give permission — and she had gone through this very deep depression, and it tested her faith. It tested her understanding of the world, and she came out of that and went to this meeting in Ruleville in 1962 and when she heard those young people and their passion and their willingness to put their lives on the line for her, she viewed them as the “New Kingdom.” So it was more than a crossroads for her. It was a moment where she could see the future in these young people, and she called them the “New Kingdom (right here) on earth.” If they were willing to stand up and risk their lives then she could, at 45, 46 years old, stand up herself. That was a crossroads. She made that choice to stand up, publicly, and move forward.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Sep 28, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

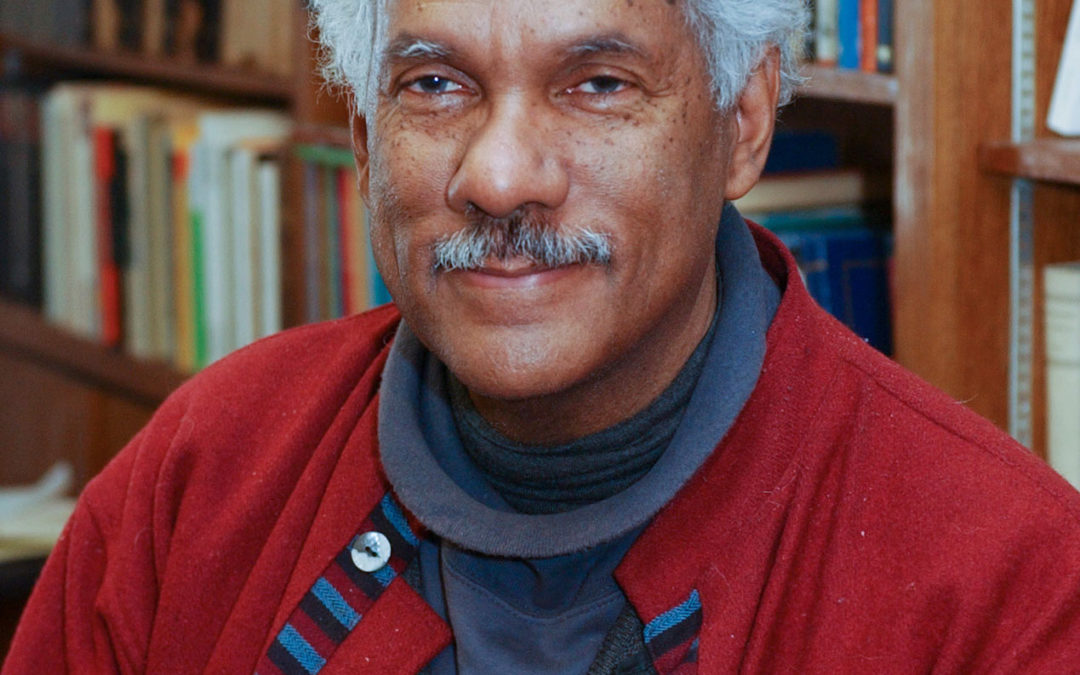

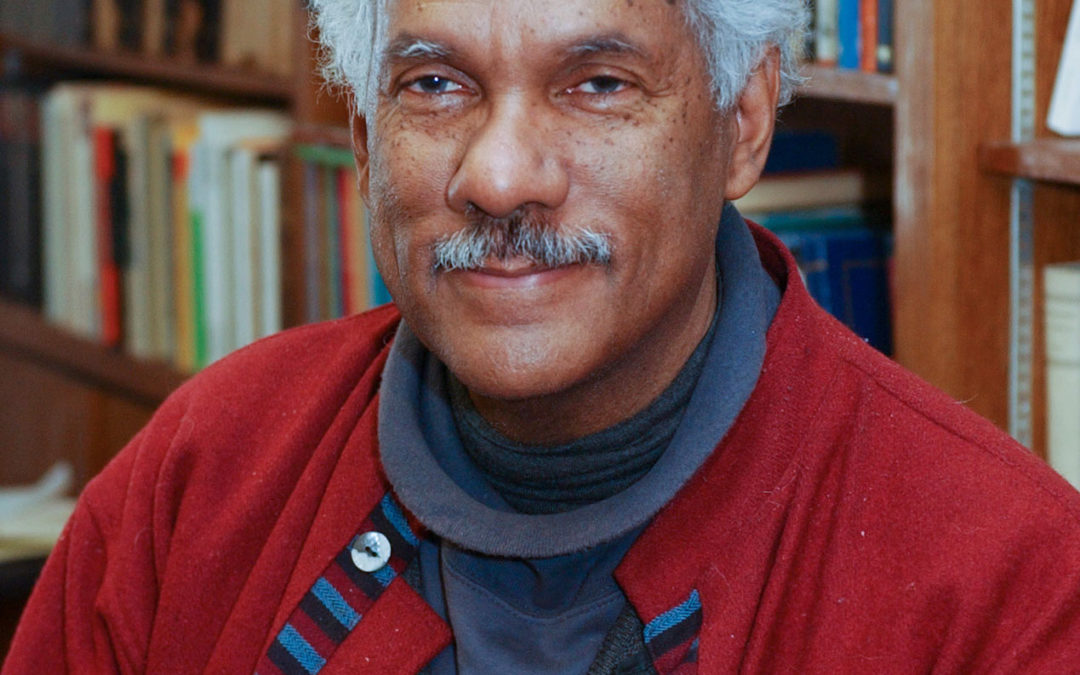

(RNS) — Albert J. Raboteau, an American religion historian who helped students and journalists enhance their understanding of African American religion, has died.

The scholar died on Saturday (Sept. 18) in Princeton, New Jersey, years after being diagnosed with Lewy Body Dementia, Princeton University announced. He was 78.

A Princeton faculty member since the 1980s, Raboteau reached emeritus status in 2013. He chaired the university’s religion department from 1987 to 1992 and was dean of its graduate school from 1992-93.

“Professor Raboteau taught me so much: how to move about the archive, how to trust and be comfortable with my questions, and how to write clearly and with sophistication,” Eddie Glaude Jr., chair of Princeton’s African American studies department, said in a Princeton statement. “His brilliance knew no boundaries. His work helped create an entire field, and he could move just as easily in the fields of literature and film.”

When a book editor came to campus seeking to learn about Raboteau’s next book, a Princeton appreciation noted, the author instead arranged a meeting with the editor and Glaude, leading to the publication of the then-graduate student’s first book.

In addition to his years of mentoring students, Raboteau also gave journalists his perspective on the history of the Black church and contemporary religious attempts to address racism.

At a 2015 Faith Angle Forum discussion, he addressed reporters on the topic ” Forgiveness and the African American Church Experience.” Raboteau said small, face-to-face cross-racial gatherings, such as Bible studies and sharing meals, could be more important than statements of apology about racism by predominantly white denominations.

“What we are as a nation is a collection of disparate stories, an ever exfoliating set of separate stories and what we need to bind us together is to be able to hear the stories of others in face-to-face encounter,” he said. “And that can be sponsored by churches; churches would be a natural place to sponsor that kind of face-to-face contact.”

Raboteau was known for his writings about African American faith, most especially the book “Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South” as well as “Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African American Religious History” and “Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans.”

An “In Memoriam” Princeton tribute described his 2002 book “A Sorrowful Joy” as a volume that reflected “the stakes of the study of African American religious history as a Black man from Bay St. Louis, Mississippi whose father was murdered by a white man before he was born and as a Christian believer whose religious formation took place first in the Roman Catholic Church and in later years in Eastern Orthodoxy.”

Across social media this week, scholars of religion described Raboteau’s personal influence on them.

“For me, Al wasn’t the usual kind of mentor,” tweeted Anthea Butler, professor of religion at the University of Pennsylvania. “He was an ideal to me about both scholarship and spirituality.”

She added, in the last tweet of a thread that seemed to give a nod to his conversion to Orthodox Christianity: “Finally (and not sure if he would a. like this or b. chastise me) but I would pay a lot of money if someone painted Al Raboteau as an icon. For me, he is the patron saint of the study of African American Religion. May he rest in eternal peace and bliss.”

Cornel West, a Princeton emeritus professor who now teaches at Union Theological Seminary, tweeted after the death of his colleague of more than four decades that Raboteau “was the Godfather of Afro-American Religious Studies & the North Star of deep Christian political sensibilities! I shall never forget him!”

Raboteau also was the author of “African American Religion,” a 1999 volume in the “Religion in American Life” series published by Oxford University Press.

He wrote in its first chapter of the historical role of slave preachers and other Black pioneers whose sermons reached free Black people as well as the enslaved.

“The growth of Baptist and Methodist churches between 1770 and 1820 changed the religious complexion of the South by bringing large numbers of slaves into membership in the church and by introducing even more to the basics of Christian belief and practice,” he wrote. “The black church had been born.”

In 2016, when the U.S. Postal Service honored African Methodist Episcopal Church founder Richard Allen with a postage stamp, Raboteau told Religion News Service: “The unwillingness of the Methodists to accept the independent leadership of Black preachers like Allen and the institution of segregated seating led Allen and (clergyman Absalom) Jones to found independent Black churches.”

Late in life, Raboteau continued to interpret lessons of religious and racial history in his 2016 book “American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals and Their Struggle for Social and Political Justice.” He said the book, which included chapters on Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer, was based on his “Religious Radicals” seminar that he taught undergraduate students at Princeton for several years.

Raboteau wrote the book’s introduction as the U.S. marked the 50th anniversary of Alabama’s Selma to Montgomery voting march.

“Memory and mourning combine in prophetic insistence on inner change and outer action to reform systemic structures of racism,” he said.

Raboteau added an anecdote about his own visit to Selma several years before with Princeton alumni and students who visited a museum close to the town’s famous Edmund Pettus Bridge, where activists had once been beaten back by state troopers. On the trip, a Black museum guide who was beaten on the bridge as a young girl encountered a retired white Presbyterian minister who had joined the demonstrations after King requested support from the nation’s clergy.

“It was a moment of shared pathos that transcended time,” he recalled. “For me it was the high point of the trip. I no longer needed to cross the bridge.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jul 21, 2021 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News |

(RNS) — Just-retired Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie is an apologist for an adaptive style of leadership. It’s what has helped her succeed as the first woman to hold many roles in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. And it’s a style of leadership she said was needed during the pandemic.

“Adaptive leadership means that you are faced with situations but do not have a solution or answer that comes from past experiences, so you have to adapt,” she said in an interview on Thursday (July 15), a week after her retirement began at the close of her denomination’s General Conference in Orlando, Florida.

“You have to know how to pivot, you have to step back, get on the balcony, survey the scene, throw out what you know or what you think you know and then find the answer that’s going to fit this issue right here.”

McKenzie, who remains the national chaplain of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority, acknowledged this approach appeals to her because that’s the way she’s lived her life as a female trailblazer in her 205-year-old denomination. In 2000, McKenzie was the first woman elected bishop and later the first to serve as president of its Council of Bishops and chair of the General Conference Commission, which organizes the denomination’s quadrennial meeting.

Now one of five women bishops elected in the AME Church, McKenzie remains ready to answer anyone who questions their ability to lead.

“Do I think women can do this? Yes,” she said. “Do I think women are called to this? Yes. Do I think the women that have been elected in my denomination have done an exceptional job? Absolutely.”

As she led AME regional districts in Africa, Tennessee and Texas, McKenzie said she focused on her work rather than her title, letting the results speak for themselves. She modeled holding babies with AIDS to show it was safe and proved it was worthwhile to develop church websites to help attract new members and it was practical to use golf tournaments as fundraisers for church projects and seminary scholarships.

As she spoke at the conclusion of the General Conference bishops’ retirement service on July 9, she thanked her husband, former NBA guard Stan McKenzie (the first male episcopal supervisor of missionary work in the AME Church), her denomination and God for their support.

“What God did for me is evidence of what God can do for you,” she said. “For if God could do this, God can do what God promises you. That can be done no matter who says it can’t be.”

McKenzie, 74, talked with Religion News Service about her journey as a female bishop, those who paved the way for her to reach that role, and what’s next for her and for her denomination.

Bishop Vashti Murphy McKenzie, center, outgoing pastor of Payne Memorial African Methodist Episcopal Church in Baltimore, bids longtime member Helen Thorton farewell on her last Sunday at the church in Sept. 2000. At left is her husband, Stan McKenzie. Photo by Carl Bower

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Looking back as the first woman bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, is there a way you would sum up your experience since 2000?

Being the first of anything, there is no book. There is no DVD. There’s no movie. There’s nobody in front of you, to be able to share back experiences of what it’s going to look like and feel like and be like and so you’re charting your own way. And as people receive you — not only as you are in your position but also receive you as a human being — and begin to see you have something to bring to the table and be able to embrace the uniqueness of my femininity. I do what bishops have to do, but I don’t do them in the same way because I’m Vashti.

Your family has long been in the journalism business, running the Afro American newspaper chain. You wrote newspaper articles starting at age 16 and as bishop you oversaw denominational publications including The Christian Recorder. What was it like to move from being in the news business to becoming a newsmaker?

It was a little bit different being on the other side of the microphone, the other side of the camera and on the other side of the notepad, really, because I grew up telling some other people’s stories. And then the shift comes where then you become the story. And so, my intention was not to have my episcopal career be about me. That my episcopal career would be about the people I serve. So I was intentional, to focus on the work, rather than the first. God didn’t just call me to be first. God called me to do the work. And so that’s what I focused on in each of the districts I served.

You mentioned in the “Echoes from the General Conference” documentary that, though 2000 was a turning point for women bishops, it was preceded by earlier actions. What and/or who paved the way?

Well, many, many women. Many women whose names were not written, who did not get a footnote, who were in the margins. Faces and names people have forgotten a long time ago. Beginning with Jarena Lee. Jarena Lee stood at her time, when Bishop Richard Allen says he’s not going to license women. But God created an opportunity and she stood, and so then off she goes to walking and preaching hundreds of miles.

Elizabeth Scott ran for the episcopacy for many, many, many years. The women who were appointed presiding elders, the women who were appointed pastors, and did fabulous work because if they didn’t, then they would never give another woman a chance.

The 2021 episcopal address, the message of the bishops to the denomination during the General Conference, spoke of longtime struggles for women to gain ordination, and the rank of bishop. What action do you think is needed still?

What seems to be difficult for the church at large — and I’m talking about the universal church, denominations at large — is the inability of embracing inclusivity, as far as women is concerned. Just because you’re at the table, doesn’t mean it’s success for all women. Just because there’s one presiding elder, one woman who is a bishop, doesn’t mean the playing field is level for all women. And so in order for that to happen, we have to be intentional, and intentional means you don’t promote or assign just because a woman is a woman. You recognize her gifts. When I ran, I didn’t run on a platform saying elect me because I’m a woman. I ran on a platform that says elect me because I’m qualified.

Was there something you’re particularly proud of achieving in ecumenical or interfaith circles?

Most of my ministry is focused within the AME Church but I preach everywhere. I have preached for the Presbyterian women, the Baptist women. I preached for the Hampton (University) Ministers’ Conference with denominations from all over, for the United Methodist Church, for the United Methodist annual conferences. And in that way, sharing prophetically also helps to shape people’s embracing women. I have preached at Catholic churches. I have spoken in Jewish communities.

I have preached in seminaries, and it’s so important for the female seminarians to be able to see someone who is their same gender, who has the same kind of uniqueness, as an encouragement to see the broader picture, to see ministry beyond your own front door.

The AME Church has voted to start an ad hoc committee on LGBTQ matters. Do you think it may be turning a corner about acceptance of LGBTQ people, just as the denomination turned a corner on women bishops 21 years ago?

I think dialogue is going to be good for the church because there are different people in different places having different kinds of conversations and to be able to have open conversation, which an ad hoc committee would provide, where the church is gathered, will be healthy and may be helpful.

Do you see an end to the ban on same-sex marriage?

I think we’re going to have to wait and see the conversation, the power of the conversation. I just think it’s just too hard to predict at this moment. We have to remember the church, the broader church, has a hard time dealing with racism. Church, period, had a hard time dealing with sexism. They have a hard time dealing with agism, classism. And now, this is the next wrestle. And after this wrestle, there’ll be another, and there’ll be another, and there’ll be another, and there’ll be another.

So now that you have reached retirement as an AME bishop, what’s next for you?

I’m going to continue with Selah (Leadership Encounters for Women, her professional women’s empowerment organization) because I have a passion for leadership. I plan to write. This is a good time to sit down and put some thoughts down on paper. And then, as they say, we’ll look into the horizon to see what also is next.

This story has been corrected to clarify that the African Methodist Episcopal Church has a ban on same-sex marriage. It does not have a ban on ordination of LGBTQ persons.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jun 8, 2021 | Headline News |

Rodman Allen hugs his mother after the 2021 Wilberforce University Commencement, Saturday, May 29, 2021, in Wilberforce, Ohio. Courtesy photo

(RNS) — There are usually lots of cheers and applause at university commencements.

But 2020 and 2021 graduates of Wilberforce University, a school affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, had an extra reason to celebrate during their ceremony on Saturday (May 29) in Wilberforce, Ohio.

Their president announced that any debts they still owed to the historically Black university had been forgiven.

“Because you have shown that you are capable of doing work under difficult circumstances, because you represent the best of your generation, we wish to give you a fresh start,” said President Elfred Anthony Pinkard. “So therefore the Wilberforce University board of trustees has authorized me to forgive any debt. Your accounts have been cleared and you don’t owe Wilberforce anything. Congratulations.”

As soon as Pinkard said the words “forgive any debt,” the masked students started screaming, shouting and jumping, prompting him to smile and laugh before he continued his surprise announcement, which was streamed live on Wilberforce’s YouTube channel.

When he added “accounts have been cleared” there were more cheers, jumps and hand-waving among the black-robed students wearing green and gold stoles.

In a statement on the university’s website, the school said the amount of debt forgiveness for both classes totals more than $375,000 for the 166 new alumni.

It said the “zero balance” was the result of scholarships from the United Negro College Fund Inc., Jack and Jill Inc. and other institutions that aided students in the spring and fall semesters of 2020 and the spring of 2021.

It noted all student also benefited from the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund established through the CARES Act. In particular, that financial assistance had previously helped the students whose balances due to the school would have prevented them from registering for their fall classes in 2020.

One student spoke of the difference the debt forgiveness will make for him in the years ahead.

“I couldn’t believe it when he said it,” Rodman Allen, now a 2021 alumnus, said in a statement. “It’s a blessing. I know God will be with me. I’m not worried. I can use that money and invest it into my future.”

During the ceremony the university also awarded posthumous doctorate degrees to civil rights leaders Fannie Lou Hamer and Medgar Evers.

Wilberforce, the oldest private historically Black school operated and owned by African Americans, was founded in 1856.

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jun 2, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

(RNS) — On the first Wednesday in May, as the centennial of the Tulsa massacre approached, the Rev. Robert R.A. Turner stood outside Tulsa City Hall with his megaphone, as he does every week.

“Tulsa, you will reap what you sow and that which you have done unto the least of these my children, Jesus said, you have done also unto me,” said Turner, 38, the pastor of Historic Vernon African Methodist Episcopal Church, captured on a video posted on Facebook.

“We come here to say, for your own benefit, you ought to do reparations not tomorrow, not even next week, not next month, not next year, but we demand reparations now!”

Turner’s Vernon AME is one of the plaintiffs in a suit filed in September that calls for the city of Tulsa and other defendants to pay reparations to relatives of victims and survivors of the May 31, 1921, massacre that destroyed a part of town known as “Black Wall Street.”

Beginning with false rumors spread though the Oklahoma city that a young Black man had assaulted a white female elevator operator, within about 16 hours, a white mob killed an estimated 300 Black people and destroyed thousands of homes, businesses and churches.

As Tulsa pauses to mark the somber centenary in its Greenwood district, where Black Wall Street was located, Turner and other Black people of faith are among those saying the time has come to repay as well as to remember.

The lawsuit argues that the tragedy is a continuing “public nuisance” that Tulsa should remedy through monetary means.

Among the suit’s petitions to the Tulsa County District Court are payments to descendants of those who were killed, injured or displaced by the massacre; development of educational and mental health programs for individuals and organizations in Greenwood and North Tulsa; and a scholarship program for “Massacre descendants” for post-secondary education in Oklahoma.

The suit states that Vernon AME Church, “founded in 1905, is the only standing Black-owned structure from the Historic Black Wall Street era and the only edifice that remains from the Massacre. Vernon’s sanctuary burned in the Massacre. The basement was the only part of the red brick building that remained.”

The church joins other plaintiffs in charging that they never received resources to recover from the trauma and damage of the massacre.

The city, responding in court documents to the suit, questioned the framing of its claims and the idea that the city’s current problems can be attributed to 100-year-old wrongs.

“At its base level, Plaintiffs are attempting to seek reparations for the events of June 1921 while working around the inherent statute of limitations problems that have thwarted other lawsuits bringing similar claims,” the city argued.

It added that the suit’s claims of continuing racial inequalities are “nebulous” and said “community wide issues such as racial disparity are caused by a number of factors and cannot be traced to specific actions or omissions to act of or by the City, nor is it a nuisance that can be simply abated by the City.”

In 2001, the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 called for reparations for the massacre, including payment to survivors and descendants, a scholarship fund, establishment of an economic development zone in the historic area, and a memorial for reburial of remains of victims found in unmarked graves.

“Perhaps this report, and subsequent humanitarian recovery events by the governments and the good people of the state will extract us from the guilt and confirm the commandment of a good and just God — leaving the deadly deeds of 1921 buried in the call for redemption, historical correctness, and repair,” wrote then-state Rep. Don Ross in the prologue of the report.

Turner, who arrived in the city in 2017 to lead his church, agrees with all of the commission’s recommendations and hopes for a full criminal investigation. His petition for reparations has been signed by more than 26,000 people.

“This is about sin and an abominable sin — racism,” said the minister, who calls the massacre a “genocide of people simply because of the color of their skin.”

Gregory Thompson, co-author of a new book, “Reparations: A Christian Call for Repentance and Repair,” said the Tulsans’ demands show how the movement for reparations has extended beyond atonement for the United States’ involvement in slavery to repairing societal ills, and that not just the federal government but local and regional officials are being called to account.

“It’s not to say that I don’t think the federal government should be involved — I do,” said Thompson, a white scholar who directs Voices Underground, a team of researchers and community members focused on the history of the Underground Railroad in the Philadelphia area. “But I think community-based reparations allow African American leaders a lot more agency in this conversation than if it’s located at the federal government, which is not equitably representative of African Americans.”

Regional reparations initiatives have become more common of late. Since the 1990s, descendants of survivors of the 1923 massacre in the majority-Black enclave of Rosewood, Florida, have received state scholarships.

In March, the Evanston City Council, in Illinois, began approving reparations that provide mortgage and other housing assistance to local Black residents to make amends for racially discriminatory housing practices. In April, Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam signed a bill mandating that five of the state’s older public universities pay for scholarships or community redevelopment programs, starting in 2022, to benefit descendants of enslaved workers who built them.

Vernon AME is one of 23 churches in Greenwood that predate the massacre, of which 13 survived, according to a tally by Faith Still Standing, an ecumenical group of congregations that have rebuilt in the area or beyond it.

The Rev. Robert Givens pastors Christ Temple Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, a congregation that was founded in Greenwood but has since moved. Its original building was still new when it was destroyed in the massacre.

“When we think of Black Wall Street, it was tremendously a thriving area of all-Black businesses,” said Givens. “So a lot of the churches were just now getting started in that area” when they were burned down.

“Nothing was ever done for them or to help them in that situation,” said Christ Temple’s trustee board chairperson, Annette Gathron, of the people who lost homes, businesses and belongings along with their churches.

Some of those whose families survived the massacre have become key figures in the city’s Black history. The late John Hope Franklin, the famed historian, was a member of Christ Temple, and his father, attorney B.C. Franklin, helped pay off the church’s mortgage on the brick building it constructed after the massacre.

Gathron said she hopes to attend some of the worship services marking the centennial.

A ” Unity Day Worship Guide ” for congregations to use on the last Sunday in May is included in an online list of options for commemorative activities.

Gathron said she also intends to keep younger members of her family aware of the history of the city where she has lived for more than 60 years.

“I think that it’s good that we are remembering and I plan to take my great-grands to some of this so they can understand the struggles that we have had,” she said.

She traditionally takes nieces and nephews visiting from across the country on a walking tour through historic Greenwood, including a stop at Vernon AME.

“I think it’s important for them to know that they can achieve because this, at one time, was a very thriving community.”

On May 31, Tucker’s 130-member church, which opened in a rebuilt sanctuary in 1928, plans to dedicate “a prayer wall for racial healing” that will include an exterior wall of the basement that survived 100 years ago.

Once built, Turner hopes it will draw people of all faiths and none for prayer and meditation. “The idea behind it is to have people of all nations come and to pray and talk to God to help us with this racial healing that we need in the world,” he said.

You can hear from Pastor Robert Turner alongside other leaders virtually tonight (June 2, 2021) at Friendship West Baptist Church in Dallas, TX as they commemorate the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 in A Sankofa Moment. Conversation will also feature Nancy St. Jacobs, VP of Community Business Development for Truist Bank, and Lamar Tyler, Founder of Traffic Sales & Profit moderated by Dr. Frederick D. Haynes III.