by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jan 13, 2022 | Headline News, Social Justice |

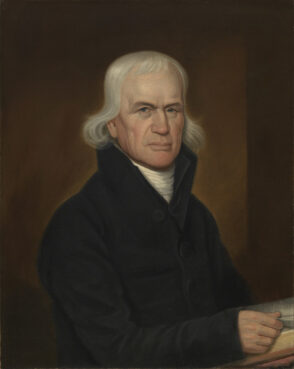

Howard Thurman was a theologian and mystic who taught at both Howard University and Boston University. Photo courtesy of Emory University

‘(RNS) — Hartford International University for Religion and Peace has launched its new Howard Thurman Center for Justice and Transformational Ministry, an expansion of its longtime Black Ministries Program, named for the 20th-century theologian and mystic.

Joel N. Lohr, president of the university that previously was known as Hartford Seminary, said the center fits into the school’s strategic plan that focuses on peace building.

“It was my hope that this would be a moment to grow, to envision a center that would do more to support students, justice and ministry,” he said at a Tuesday (Jan. 11) webinar that officially launched the center and was attended by alumni, as well as Thurman’s grandchildren.

The center, which is a $2 million project, is supported by a $1 million grant from the Lilly Endowment Inc. The grant will support a resource center, pay for a Black church scholar and assure that students will not be excluded if they cannot afford the coursework.

The HTC will be led by Bishop Benjamin Watts, who will also continue to lead the Black Ministries Program founded in 1982 by the late Christian Methodist Episcopal Senior Bishop Thomas Hoyt.

“The center’s North Star will be Thurman’s insistence on social justice and responsibility within a spiritual framework,” said Watts in an introductory video during the launch event.

In live comments, Watts spoke of plans to move beyond the center’s regional focus in its two-year certificate course and to become a national model of theological training for pastors and lay people. He said the center also wants to expand the training to include health, wellness and trauma education.

“Those of us of faith have to find ways to continually engage with other persons, and particularly our youth who seem to be falling away from our worship centers,” he said.

During a live interview, Watts asked the Rev. Walter Fluker, editor of “The Papers of Howard Washington Thurman,” to describe the center’s namesake, who died in 1981.

“Thurman, like great mystics — the Dalai Lama, Bishop Tutu — if you meet them, they’re always laughing, because they understand the deep, tragic sense of life and it’s only because of their deep sense of the tragic that they’re able to look at the world and laugh at the world,” said Fluker, a professor at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. ”To meet Howard Thurman is to meet not a detached mystic unconcerned about the affairs of the world, but a very earthly human being.”

The launch event also featured video comments from the Rev. Andrew Young, a longtime civil rights activist who worked with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and is an alumnus of the Connecticut university, and an interview with former Spelman College President Beverly Daniel Tatum, who earned a master’s in religious studies from the school.

READ THIS STORY AT RELIGIONNEWS.COM

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Nov 9, 2021 | Commentary, Headline News |

(RNS) — Former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell, known as a four-star general and as a onetime secretary of defense, was remembered at his funeral at the Washington National Cathedral Friday (Nov. 5) as a man of the Episcopal faith.

(RNS) — Former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell, known as a four-star general and as a onetime secretary of defense, was remembered at his funeral at the Washington National Cathedral Friday (Nov. 5) as a man of the Episcopal faith.

Longtime colleague and friend Richard Armitage, who served as deputy secretary of state under Powell, recalled how their regular 7 a.m. morning calls shifted to 9:30 on Sunday mornings, after his supervisor had returned from church.

“Colin loved the church: He loved the ceremony. He loved the liturgy. He loved the high hymns, which made him extremely happy,” said Armitage, who served with Powell in the State Department during the George W. Bush administration, during the private ceremony that was livestreamed on YouTube.

“And he would answer the same way every Sunday. He said, ‘Oh yes, I was at church. And I want you to know I’m in the state of grace.’ And I would answer the same way every Sunday: ‘Colin, if you’re not in the state of grace, who among us is?’ And that was every day for almost 40 years, the same opening remarks.”

Powell, who died Oct. 18 from COVID-19 complications, was honored at a nearly two-hour private ceremony. Hundreds of people gathered under the cathedral’s neo-Gothic arches, including President Biden and two former presidents, Barack Obama and George W. Bush, and their wives, and former Secretary of State and first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton.

“With faith in Jesus Christ, we receive the body of our brother Colin Luther Powell for burial,” said Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry, who met the general’s casket at the doors of the cathedral with Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, leader of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington.

Some family members of Powell, 84, had key roles in the service that mixed the high church liturgy of the cathedral with the military precision of uniformed service members bearing Powell’s coffin and escorting his family.

His son, former Federal Communications Chairman Michael K. Powell, gave a tribute, along with Armitage and former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who preceded Powell in that position. His daughter, Annemarie Powell Lyons, read from the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Micah: “And what does the Lord require of you but to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?”

The Rev. Stuart A. Kenworthy drew on that Scripture as he spoke of Powell’s faith.

“Colin knew his God through all his years,” said Kenworthy in his homily, a role the former Army National Guard chaplain also played at the 2016 funeral of former first lady Nancy Reagan. “His faith was of first importance, and his life was marked by those words of the Prophet Micah.”

He also encouraged those remembering Powell to embrace their Christian faith.

“God raised Jesus so that you and I might share in his resurrection, and if you turn to him and accept him in faith, he will come into you and raise you into that new and eternal life now,” Kenworthy preached. “Just as he has for your beloved Colin, who now stands upon another shore and in a greater light, with that multitude of saints that no mortal can number.”

Prior to the homily, the Rev. Joshua D. Walters, rector of the Powell family’s church in McLean, Virginia, read words of Jesus from the Gospel of John: “Do not let your hearts be troubled. Believe in God, believe also in me.”

Congregants, masked during the continuing pandemic, stood to sing the hymns “Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee” and “Precious Lord.” Soloist Wintley Phipps sang “How Great Thou Art.”

In an earlier statement issued after Powell’s death, Curry noted Powell was a lifelong Episcopalian.

“I pray for his family and all his many loved ones, and I give thanks for his model of integrity, faithful service to our nation and his witness to the impact of a quiet, dignified faith in public life,” the presiding bishop said at the time. “He cared about people deeply. He served his country and humanity nobly. He loved his family and his God unswervingly.”

Though not generally known for his ties to religion, Powell was noted for comments he once made about then-Senator Obama’s faith.

Obama, in a statement released on the day of Powell’s death, spoke of his deep appreciation of Powell’s endorsement of his presidential candidacy when the general had been affiliated with past Republican administrations.

“At a time when conspiracy theories were swirling, with some questioning my faith, General Powell took the opportunity to get to the heart of the matter in a way only he could,” said Obama in the statement, referring to rumors that he was a Muslim.

At the time, Powell said, “The correct answer is, he is not a Muslim; he’s a Christian.”

But then Powell added a follow-up: “But the really right answer is, ‘What if he is?’ Is there something wrong with being a Muslim in this country? The answer’s no, that’s not America. Is there something wrong with some 7-year-old Muslim-American kid believing that he or she could be president?”

Powell also was among the top picks of likely voters who were religious and considering potential vice presidents when the then-senator was seeking the presidency in 2008.

But Armitage and other speakers mostly put politics aside as they recalled the man who was their friend, family member or colleague.

The former deputy secretary of state noted he and Powell had different preferences for hymns. Armitage recited the final verse of “Rough Side of the Mountain,” which speaks of standing “before God’s throne” when the race of life has concluded.

“Be real quiet,” Armitage told the congregation. “Listen real carefully. And you might hear our savior say, ‘Colin, welcome home. And here’s your starry crown.'”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Nov 4, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

(RNS) — Two and a half centuries ago, Francis Asbury arrived in the United States from Great Britain, bringing with him what would become the Methodist faith. He went on to spread it across the country, with St. George’s Church in Philadelphia as his home base.

St. George’s will mark the occasion of Asbury’s arrival with a weekend of events at the end of October. But the historic church, which remains the oldest continually used Methodist building in the United States, is also the starting point of three African American churches and one denomination after a “walkout” by Black worshippers.

Over time, recounts the Rev. Mark Salvacion, St. George’s current pastor, African Americans —some recently freed from slavery — were segregated to the sides of the church, to the back of the building and to a balcony, preventing them from receiving Communion on the church’s main floor.

Salvacion describes this and other parts of St. George’s history in the church’s “Time Traveler” program for teen confirmation students learning about their faith and in classes of middle-age adults training to become certified lay ministers.

Teenage confirmation students attend a “Time Traveler” program at Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia in 2018. Photo courtesy of HSG

“It’s not just telling happy stories about Francis Asbury itinerating to West Virginia,” said Salvacion, pastor of what is now called Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church. “It’s uncomfortable stories about race and the meaning of race in the United Methodist Church.”

The turning point for many African American worshippers, already dissatisfied with mistreatment, was a Sunday morning in the late 1700s. Lay preacher Richard Allen saw another Black church leader, Absalom Jones, forcibly pulled up while praying on his knees at St. George’s.

That led Allen and some of the other Black attendees to leave what was then known as St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church and strike out on their own — in different ways.

Portraits of Absalom Jones, from left, Harry Hosier and Richard Allen in Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church museum in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of HSG

“This raised a great excitement and inquiry among the citizens, in so much that I believe they were ashamed of their conduct,” wrote Richard Allen in his autobiography. “But my dear Lord was with us, and we were filled with fresh vigour to get a house erected to worship God in.”

In 1791, Allen, who had been a popular preacher at St George’s 5 a.m. service, started what is now Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Asbury dedicated its first building, a former blacksmith shop, in 1794.

“Here’s Asbury and he comes in and he still has this kind of relationship with Richard Allen that is more than just collegial,” the Rev. Mark Tyler, current pastor of Mother Bethel, said of the men who were the first bishops of the Methodist and AME churches, respectively.

“I mean, you go out of your way as the representative and the saint of Methodism in America and you dedicate Mother Bethel. That is a statement that you’re behind this and endorsing it.”

Bronze statue of Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, on the property of Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia on July 6, 2016. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

In 1816, after winning a court battle for its independence from the Methodist Episcopal Church, Allen started the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the nation’s first Black denomination.

Jones went on to serve as a lay leader of the African Church that began in 1792. Two years later, the congregation became affiliated with the Episcopal Church and was renamed the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. Jones was ordained a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802.

Arthur Sudler, director of the Historical Society & Archives at the 1,000-member church, said the 250th anniversary of Asbury’s U.S. arrival is significant not only for the three Philadelphia congregations that began after discord with St. George’s but also for the city and the three denominations they now represent.

“It’s an epochal moment simply because Francis Asbury’s role in helping develop Methodism in America, in part through his participation there at St. George’s, is one of those factors that gave birth to the Black Christian experience in Philadelphia,” he said. “And in America more broadly, because of the seminal role of Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, and Harry Hosier and their connections between what became these three denominations, the AME Church, the United Methodist Church and the Episcopal Church.”

Service at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in 2019. Photo by Dale Williams for D’Zighner Studios

Hosier initially stayed at St. George’s with other Black attenders who did not leave with Jones and Allen. He also was a closer colleague to Asbury than the other two men, having been a traveling companion who preached with the Methodist leader across the South. Allen, a free man, had declined the offer, avoiding a risky return to the region of the country where slavery remained legal.

Hosier helped found another Philadelphia Methodist congregation, which initially met in people’s homes and eventually became known as Mother African Zoar United Methodist Church. Asbury dedicated its building in 1796 and preached there a number of times, according to the United Methodist Church’s General Commission on Archives and History.

After it celebrated its 225th anniversary, Mother Zoar retained its name but merged with New Vision United Methodist Church in north Philadelphia, with a current average of 75 people at in-person worship services. It thus remains the oldest Black congregation in the United Methodist tradition in continuous existence.

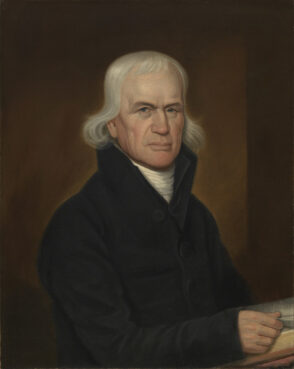

Portrait of Francis Asbury in 1813 by John Paradise. Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery/Creative Commons

Given the steps of Allen and Jones, why did Hosier and other Black worshippers who once prayed at St. George’s remain within the Methodist Church?

“That is a million-dollar question,” said the Rev. William Brawner, the part-time pastor of Mother Zoar.

He said he assumes “those who left with Absalom, those who left with Richard were tired and figured that they could not change the system of injustice from the inside.” The founders of Zoar chose a different approach, hoping that remaining Methodist would help “change the hearts and minds of the people that were literally oppressing them.”

All these years later, Brawner said he does not judge the different decisions made by African American worshippers at St. George’s, who were unable to freely use spiritual practices that were different from those of white congregants and reflected beliefs some had brought with them from Africa.

“I think people left because of feeling uncomfortable and unaccepted in one place,” he said. “So the split could be celebrated now because of what has become of the split, but people didn’t split out of privilege. People split out of pain. They split because they were hurting.”

The emotions arising from the divisions transcended the centuries.

The Rev. Mark Tyler. Courtesy photo

Tyler, whose church has more than 700 members today, recalled the 2009 service when congregants of Mother Bethel worshipped at St. George’s for what was believed to be the first joint Sunday morning service since the 1700s. As the preacher for that day, he said the gathering was a “cathartic moment,” prompting many of his church’s members to weep.

Salvacion and the clergy of the other churches say occasional joint gatherings have continued since then, such as some of the congregations sharing Easter sunrise services and the annual Episcopal Church observance honoring Absalom Jones.

St. George’s currently has about 15-20 worshippers and a membership of about 50. It expects dozens of United Methodists and invited guests from other churches to attend the Oct. 30-31 commemoration.

Its pastor also expects exchanges and shared events will continue in the future among the congregations whose first members left his church building.

“We all view this history as being common history that we share,” said Salvacion, an Asian man who is one of St. George’s first pastors of color.

Interior of Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative Commons

Tyler said the ongoing connections between St. George’s and Mother Bethel probably weren’t envisioned by anyone two centuries ago.

“The current relationship of these two congregations is, in some ways, a sign of hope for what’s possible,” he said. “If it can happen in these two congregations maybe it’s possible for us as a country and as a world. I have to take it for what it is — just a small sign of hope, in spite of all the kind of guarded optimism that I have.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Nov 2, 2021 | Headline News |

(RNS) — Sen. Raphael Warnock, who continues to pastor his historic Atlanta church while serving as Georgia’s first Black U.S. senator, has received the Roosevelt Institute’s Freedom of Worship Award in a ceremony focused on racial justice.

“I really felt that the strength of his pastoral voice was unique,” Anne Roosevelt, granddaughter of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and board chair of the institute, told Religion News Service hours before Warnock was honored in a Wednesday (Oct. 13) ceremony.

“And now, he’s in this new role in addition to his role as pastor at the church, but his voice is consistently counseling, teaching, making himself vulnerable in order to help the rest of us make sense of the world,” she said.

Warnock, the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was once co-pastor, was honored on the same evening with New York Times journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones. She was awarded the institute’s Freedom of Speech and Expression Award after spearheading the newspaper’s 1619 Project that explored the history and legacy of slavery in the U.S.

The senator, interviewed during the virtual ceremony by Community Change President Dorian Warren, said he views himself as a “pastor in the Senate,” reminding the powerful not to ignore people with no wealth.

Dorian Warren, left, interviews Sen. Raphael Warnock during the Roosevelt Institute’s Four Freedoms Awards, Wednesday, Oct. 13, 2021, in a virtual ceremony. Video screengrab

“For me, faith gets engaged in the messiness of worldly struggle; it’s not hidden behind stained-glass windows,” Warnock said. “You probably could step over (the poor) but you shouldn’t. God warns us not to do that. My work is putting them always at the center. Because in their faces we see the face of God.”

The respective names of the Four Freedoms Awards are taken from fundamental liberties laid out in a 1941 speech to Congress by Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was elected to four terms in the Oval Office. He spoke of the “freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world.”

His granddaughter, 73, said the institute, which has published reports and fact sheets on racial inequities, chose to take an “extra step” toward racial justice through this year’s awards.

“This is one event where we could say, ‘So what does it mean to be an anti-racist giver of awards?’” she said. “And to challenge ourselves and bring it to our own consciousness.”

Anne Roosevelt opens the Roosevelt Institute’s Four Freedoms Awards virtual ceremony, Wednesday, Oct. 13, 2021. Video screengrab

Anne Roosevelt acknowledged that African Americans and other people of color were often left out of her grandfather’s New Deal reforms.

“We are still falling short of making sure that we deliver the same benefits of our democracy to every person in our country,” she said.

While Anne Roosevelt’s grandfather and grandmother, Eleanor Roosevelt, were lifelong Episcopalians, she said she was raised Catholic and is not currently affiliated with a denomination. But as a member of the committee that nominated Warnock for his award, she said she appreciates him as a leader and as a person of faith.

“I don’t often reflect on Jesus, but when I do, I picture him being surrounded by the people who followed him,” she said. “He taught them how to live, how to live as the fullest and best expression of humanity. And I feel like Senator Warnock is in that mode.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 12, 2021 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Heritage |

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in 2016. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

(RNS) — A century and a half ago, nine young men and women embarked on a trip from Fisk University, establishing a tradition of singing spirituals that both funded their Nashville, Tennessee, school and introduced the musical genre to the world.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, based at the historically Black university founded by the abolitionist American Missionary Association and later tied to the United Church of Christ, started traveling 150 years ago on Oct. 6, 1871. They since have continued to sing so-called slave songs such as “Down by the Riverside” and “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and stood on stages from New York’s Carnegie Hall to Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium.

Musical director Paul Kwami has led the group since 1994 and sang with it when he was a Fisk student in the 1980s. Then and now he views the songs as not only expressions of the religious beliefs of enslaved people, but also of the original singers and the ones who continue to sing today.

“There are songs like ‘Ain’t-a That Good News,’ which is a song that talks about having a crown in heaven, having a robe in heaven,” said Kwami, a member of a nondenominational Full Gospel church in Nashville. “Well, they’ve never been to heaven, but then they’re singing about heaven — that’s an expression of faith.”

Kwami, a native of Ghana, in West Africa, talked with Religion News Service about how the ensemble began, who should sing spirituals and which of the songs are his favorites.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers in Jubilee Hall at Fisk University on Oct. 29, 2020. Photo by Bill Steber and Pat Casey Daley

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers won their first Grammy in 2020 for an album that celebrates almost a century and a half of music. What does that say about the endurance of the group and the music that they have sung for so long?

The album was actually produced on the (university’s) 150th anniversary. But then, of course, it is the Fisk Jubilee Singers who won the Grammy, which actually makes me realize that people still recognize who the Fisk Jubilee Singers are. And people still appreciate the music. Additionally, people realize Fisk Jubilee Singers are artists and do not limit themselves to just Negro spirituals. There’s versatility in our choice of music when we have celebrations.

How do you define spirituals, and differentiate them from other forms of African American music sung in Black churches and beyond?

The Negro spirituals are songs that were created by the slaves during their time of slavery. But when we talk about music like jazz or blues or gospel, those genres of music came long after the Negro spirituals were established. And some people even say these other forms of music were birthed out of the Negro spirituals.

When we talk about the Negro spiritual and, say, gospel music, the performance styles are completely different. Gospel music simply deals with church music with a lot of instrumental accompaniment, clapping, a lot of improvisation. But with the Negro spiritual, even though there may be some improvisation, it doesn’t involve a lot of improvisation. Traditionally, Negro spirituals don’t call for instrumental accompaniment.

When the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing, the music is a cappella. The original Fisk Jubilee Singers transformed the Negro spiritual into an art form or concert spiritual. And because of that, clapping, for example, is not recognized as part of a performance of Negro spirituals.

Spirituals are known for their layers of meaning, some of which were hidden to slave masters. Can you give an example of one that is often sung by Fisk Jubilee Singers that reflects that?

One we often sing is “Steal Away to Jesus.” (One) meaning is that we will run away to the North — because we’re stealing away to Jesus — and Jesus was referring to a place of freedom.

When George White, a music professor and Fisk’s treasurer, decided to have singers from the school perform the spirituals for white audiences as fundraisers, was his idea supported by many or was it controversial or both?

To leave Fisk with a group of students to go on a tour, singing to raise money — that was opposed. The administration at Fisk at that time did not believe he would succeed. They thought this was more of an experimental adventure because no one had ever done that. He was not sure of how audiences would receive Black young people singing so he taught them to sing Western (and European) classical music with a hope that would be more attractive to the various audiences. The Fisk Jubilee Singers were also not willing to sing the Negro spirituals because those songs were very sacred to them. But eventually, they started singing the Negro spirituals to the delight of their audiences.

The spirituals were “concertized” for performance for these fundraisers. Do you think anything was lost as the songs moved from the field where slaves had labored to concert halls where people paid to hear them sung?

I don’t think anything was lost. I read a quote by one of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers, and in this book he transcribes some of the songs they sang. I look at the melodies and they’re the same melodies we sing except the arrangements may be different.

How were the singers received at a time when slavery had just ended and African Americans were not welcome in many venues that were segregated?

Originally, they were not well received. There are accounts where people would go into the concerts, listen to the Fisk Jubilee Singers sing and not even give donations. There are accounts of Fisk Jubilee Singers going into hotels and hotel owners, realizing they were Black people, turned them away, wouldn’t give them a place to sleep or food to eat. There was a time when George White was able to purchase first-class coach (train) tickets for them but they were refused admittance into the first-class coaches because of the color of their skin. There is a painting somewhere that someone depicted them looking more like animals on stage singing. So they did go through those types of experiences as they went on their first tour. But I always say the young Fisk students who went out to raise funds for the university kept their focus on their mission and also were able to sing their songs and win the hearts of many people.

There have been debates over whether white people singing spirituals is a form of cultural appropriation. And I wonder where you stand on that issue.

As a musician I don’t agree with that because growing up in Ghana, we were taught songs like the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s “Messiah.” The performance of music, I don’t believe should be limited to one specific culture. Because music, rather, brings people together. I would rather encourage people of every culture to learn music of other cultures.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers sang with The Erwins, a Southern gospel group, in February, including the song ” Watch and See.” How often do the Fisk singers sing music other than spirituals and is that generally well received, or are they criticized for not sticking with the music tradition for which they’re known?

I think one of the reasons we won the Grammy is because we sang with other people and the album consists of a variety of music that actually would not be classified as Negro spirituals. The album consisted of country music. We had some blues. We had gospel. We do want to be remembered as an ensemble that sings Negro spirituals but when there are occasions that call for us to sing other types of music and if it fits into our schedule, we are going to do so.

Do you have a favorite spiritual sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers and, if so, which one and why?

I have a lot of favorite spirituals. One of them is ” Lord, I’m Out Here on Your Word.” I like that spiritual because it’s a song that helps me to be committed to my work. A line in the song says “If I die on the battlefield, Lord, I’m out here on your Word.” That is telling me that no matter what goes on, I am out to serve God. And I know he is a faithful God. And I have to be faithful to him as well. If I’m serving him, then no matter what’s going on, I trust him to provide whatever I need to succeed in my work.

Another is “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.” I love that song, again, because it gives me the idea that God takes care of us.

(RNS) — Former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell, known as a four-star general and as a onetime secretary of defense, was remembered at his funeral at the Washington National Cathedral Friday (Nov. 5) as a man of the Episcopal faith.

(RNS) — Former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell, known as a four-star general and as a onetime secretary of defense, was remembered at his funeral at the Washington National Cathedral Friday (Nov. 5) as a man of the Episcopal faith.