by Angelita Clifton | Dec 14, 2022 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Heritage |

(RNS) — Two months ago, I stood in Providence Baptist Church in Monrovia, Liberia, listening to the stories of Africans and Americans — the latter freed from slavery in the United States — who had banded together to establish the first republic on the continent of Africa two centuries before.

Providence, the oldest Baptist church in the West African country and the second oldest on the continent, was founded in 1822 by the Rev. Lott Carey, who had come as a missionary to the fledgling country and had brought a team of African American settlers home. Now, 200 years later, the Rev. Emmett L. Dunn, CEO of the Lott Carey Foreign Mission Convention, had brought a team of African Americans home.

I have traveled to several countries in Africa, and each one is imprinted on my heart in a special way. But hearing the stories of the African American settlers was cause to pause. I connected with the history of Liberia in a way I didn’t expect. I felt blessed beyond measure.

Landing in Liberia my spirit leaped like the baby in Elizabeth’s belly when greeting Mary, the mother of Jesus. The sights and sounds of Liberia greeted my senses, sending my head and my heart into overwhelming joy.

The Rev. Lott Carey. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

In Liberia, I was at home. Home in the land of my ancestors on World Communion Sunday. Home, where a sense of “double consciousness” — a concept coined by W.E.B. DuBois to describe African Americans’ sense of dislocation from Africa and ourselves — liberated my thoughts and linked them to my theology in a free-spirited dance of deliverance.

It’s often said we must step back before we step forward. Walking in the footsteps of Lott Carey in the motherland afforded us the opportunity to do just that.

Born enslaved in 1780 in Charles City County, Virginia, Carey became a disciple of Jesus in 1807, purchased his freedom in 1813, and led the first Baptist missionaries to Africa from the United States in 1821.

After settling in Liberia, Carey and his pioneering missionary team engaged in evangelism, education and health care. He served as a missional and civic leader until his death in 1828.

Our pilgrimage relived aspects of this journey and the experiences of his team. We explored Providence Island, where Carey landed in Liberia in early 1822. Before we landed in Liberia, Dunn told us, “We expect that this journey into the past will bring home to us the love and sacrifice of those who walked this journey before us.”

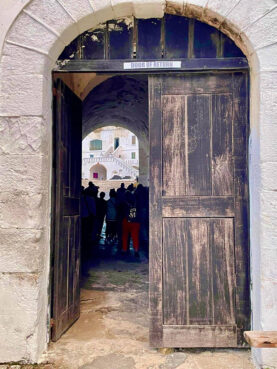

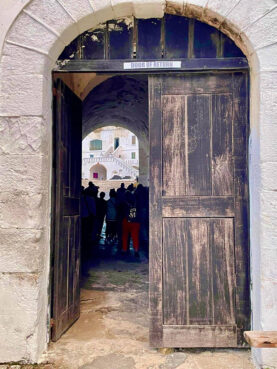

The Door of Return at the Slave Castle in Cape Coast, Ghana. It was once dubbed “The Door of No Return,” signaling the last time enslaved persons would see their homeland. Courtesy photo

Our next stop in Africa took us nearly 1,000 miles east along the coast of the Assin Manso Slave River and the Cape Coast castle in Ghana, unofficially dubbed “the Door of No Return” by our Ghanian sisters and brothers, through which so many of our ancestors were shackled and shipped into the slave trade in the New World. It has become a portal for African Americans, pulling us back to Ghana.

Before walking to the Slave River, where my ancestors received their first bath after being captured and their last bath before being carted off to the Americas, we held a ceremony of protection over Lott Carey’s life. In my sanctified imagination, my African ancestors’ prayers came to fruition in the proclamation made that day. What was meant for evil, God had used for good some 400 years later.

How ironic is it? In a whitewashed slave castle used to destroy the African spirit, a group of spirited African Americans reconnected with a long-lost history, historically whitewashed in American culture and the church universal.

My Bible says, “Be steadfast and persevering, my beloved sisters and brothers, fully engaged in the work of Jesus. You know that your work is not in vain when it is done in Jesus’ name.”

It was in that spirit that the last leg of our journey in homage to Lott Carey ended with saluting our ancestors on the same shores where they passed, returning where no return was promised. In the Twi language of Ghana, “sankofa” is a word meaning “go back and get it.” We did.

(The Rev. Angelita Clifton is president of Women in Service Everywhere and an associate minister at Fountain Baptist Church in Summit, New Jersey. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

by Dawn Herzog Jewell | Aug 22, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

SHARING THE BREAD OF LIFE: When not making biscuits at a local restaurant, Democratic Republic of Congo refugee Benjamin Kisoni pastors a congregation of African immigrants in Tennessee. He awaits asylum in the U.S. and dreams of reuniting with his family. (Photo by Dawn Jewell)

Benjamin Kisoni’s recent life reads like the story of a modern-day Joseph. But instead of donning a fine multicolored robe, he ties apron strings in pre-dawn stillness. His fingers freeze mixing chilled buttermilk and flour. He is preparing the day’s first biscuits at the fast-food restaurant Bojangles’ in Jonesborough, Tennessee.

Until three years ago, Benjamin had never tasted a biscuit in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Amidst the region’s ongoing turmoil, he was pastoring a Baptist church and publishing a Christian youth magazine. But in 2009, five times men assailed his house, seeking to kill him. Each time Benjamin evaded them. Desperate, he fled to the U.S., leaving behind his wife and eight children (ages 14 to 30) and effectively shutting down his family’s printing business.

Benjamin was targeted because he pursued a court case for his brother’s assassination. Hired gunmen had murdered his brother, a veterinarian and businessman respected for his humanitarian works. Local influential leaders had feared his brother’s increasing popularity.

“I love my country and wanted to help change it by writing. I never imagined I’d be chased from it,” he says. He and his wife reluctantly agreed that his leaving the DR Congo was the best chance they had for everyone to survive. So in May 2009, the beleaguered pastor arrived with one suitcase in small town America, welcomed by his sister and her husband.

Since then, Benjamin’s faith has been refined. After applying for asylum and while awaiting a work permit, Benjamin penned his story on God and suffering to encourage his fellow countrymen. “The ink which wrote this book is my tears,” he says. The book, “God, Where Are You?” will be released later this year by Zondervan’s Hippo imprint.

Biscuits for Jesus

Five days a week Benjamin rises at 3 a.m. to pray and read Scripture. His eight-hour shift begins at 4:30. He has honed the science of Bojangles’ made-from-scratch buttermilk biscuits.

“It’s non-stop work,” he says. But God prepared Benjamin via his Master of Theology thesis on the ethics of work years ago.

Last year Benjamin was promoted to Master Biscuit Maker, training new hires from other restaurants. On their first day, he tells each trainee: “I’m a Christian, I love God…The manager may be present or not, but I know God is there. I’m working to please God.”

God, in turn, has blessed the work of his hands. Business has improved at Benjamin’s Bojangles’ location since he started working there, his boss told him. Three times his manager has nominated him “employee of the month.”

Each month Benjamin wires home a large portion of his meager salary to provide food, medicine and rent for his family. It’s not how he imagined supporting them or rebuilding his nation. But he has accepted God’s plans.

Silent worship carries Benjamin through hours of biscuit-making. As the batter forms a ball, he softly sings in French:

“Here is Good News for all who are disappointed;

He offers better than anything we’ve lost,

Because what we see is not all there is,

His provision never ends…” (English translation)

“I used to think you can go through suffering and then reach victory on the other side. But I’ve learned that when you are in the midst of suffering and have hope in God, that is victory,” he says. Like Joseph, this suffering servant in exile has excelled, trusting in God’s plan.

An African Billy Graham

God keeps confirming the strange twists of Benjamin’s life. Twelve years ago, he dreamed he was helping to build a church, oddly within a bigger church. Today Benjamin is senior pastor to a fledgling congregation of local African immigrants. It meets within the larger American Grace Fellowship Church.

On a recent Sunday, 50 men and women, and more than 25 children from Ghana, Liberia, South Africa, Ivory Coast, the DR Congo and Cameroon filled chairs. The International Christian Fellowship formed in 2009 out of a Bible study to meet cultural needs that American churches couldn’t.

From the pulpit, Pastor Benjamin preaches the Word clearly and simply; Billy Graham is his life-long model. As a pastor’s son, a young Benjamin devoured each new issue of Graham’s Decision magazine. Today he avoids theological debates and exhorts congregants to imitate Jesus. The church is slowly expanding.

Besides discipling fellow Africans, Benjamin has helped Bryan Henderson, a bi-vocational pastor and financial advisor, grasp God more clearly. The two men email, pray and meet regularly as friends and accountability partners. “I’m white, he’s black. I grew up with privilege and he grew up with poverty,” Bryan says. “We had nothing in common, but everything in common. We had the Holy Spirit guiding us.”

BI-VOCATIONAL BROTHERS: Bryan Henderson (left), a pastor and financial advisor, met Benjamin during a time of personal despair. “He helped me see that man does not live on bread alone,” says Bryan. (Photo courtesy of Bryan Henderson)

The two men met shortly after Bryan had lost his job with financial giant Merrill Lynch. Benjamin’s deep faith amidst persecution and trials “really helped me see that man does not live on bread alone,” Bryan says. Now they discuss church leadership issues, American and African culture, and Scripture passages.

A strong daily dose of God’s word sustains Benjamin’s hope. “People here want fast food, fast cars, fast this, fast that. They haven’t learned to wait patiently on the Lord,” he says.

Recently he resonated with the three women who carried spices to Jesus’ tomb, despite awareness they couldn’t budge the boulder at the entrance (Mark 16). “The women could’ve stayed home, but they didn’t,” he says. “So I said, ‘God, I have many stones in my way. I believe you will remove them.’”

A Place to Call Home?

The biggest stone in Benjamin’s life is his asylum case. Last year the U.S. granted asylum to about 25,000 people seeking sanctuary, although three times as many applied here. Like refugees, asylum seekers flee their home countries because of persecution or well-grounded fears thereof, based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

Back home, Benjamin is sure he would be killed. His family is scattered across the eastern DR Congo, too afraid to return to their house but tired of living in limbo. Recently his daughter texted him, “Dad, I want to go back home. If they will kill me, let them kill me.”

Back home, Benjamin is sure he would be killed. His family is scattered across the eastern DR Congo, too afraid to return to their house but tired of living in limbo. Recently his daughter texted him, “Dad, I want to go back home. If they will kill me, let them kill me.”

This May an immigration judge denied Benjamin asylum, claiming inadequate grounds. His lawyer is appealing, but the process could last years.

Massive backlogs of asylum cases sit in the vastly under-resourced U.S. court system, says Lisa Koop, managing attorney of the National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC), a Chicago non-profit. Anxiety for family members still facing danger back home is a huge stressor for asylum seekers, Koop says.

In recent months, fighting between marauding militia and the army has increased in the lush green hills of eastern DR Congo, near Benjamin’s hometown. Despite peace accords signed in 2003, 5 million people have died since 1998 in the world’s deadliest conflict. The current battle for power, the region’s mineral wealth, or security originates in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, and the subsequent flight of Hutu civilians and militia into the DR Congo.

Meanwhile, Benjamin looks beyond the American dream, “longing for a better country, a heavenly one,” he says (Hebrews 11:14).

“I trust God because He’s sovereign. I’m not asking the ‘why’ questions,” he told Bryan after his case was denied.

The final pages of Benjamin’s story are unwritten. Meanwhile, reads his book’s epilogue: “I thank God for my suffering. He made himself known to me, and through them he has allowed me to comfort others.”

>>Take action: sign up for action alerts on issues and legislation on immigration reform from the NIJC.

by Christine A. Scheller | Oct 14, 2011 | Feature |

Dr. Palmer Chinchen is pastor of The Grove church in Chandler, Arizona, where he puts not only his advanced training in intercultural studies to use, but also the lessons he learned as a missionary kid growing up in Liberia. Chandler holds a doctorate in educational studies and is author of two books: True Religion and God Can’t Sleep: Waiting for Daylight on Life’s Dark Nights. UrbanFaith talked to Chinchen about his ministry values and about God Can’t Sleep. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

UrbanFaith: What is your primary calling as a pastor?

FAITH IS NOT PRIVATE: Arizona pastor and author Dr. Palmer Chinchen.

Palmer Chinchen: First, it’s to lead our people to know God and to know him deeply and intimately, and to have a rich, authentic relationship with him. With that comes the challenge to inspire them, lead them, and equip them to take his message of hope and to give our lives away to change what’s not right in this world, to love people that hurt in places that are broken.

What is the greatest challenge that you face in your ministry?

The biggest challenge right now is that I’m feeling like Christians in this country have historically and up to the present made our spirituality very personal. We talk about it in those terms as though it’s a private, inner relationship with God that happens on the inside. We limit it sometimes to our soul or to our mindset; it’s something cognitive. What I’m challenged with is trying to get people to see that when Jesus was here, he meant for us to live out the kingdom of God. Our lives are meant to be his vessels for changing not just what people believe, but changing the circumstances in which they live.

What sustains you spiritually, emotionally, and physically?

My wife, first of all. Walking with God with her is maybe the only way I’ve been able to do what I’ve been doing for the last 20 years. Getting to know the pieces of the Bible that I missed early in my life has given me new energy and inspired me in new ways. In particular, exploring Jesus’ teachings around his kingdom and the “nowness” of that this last year has been absolutely reenergizing for me. And then, the people that I work with have had a profound influence in keeping me encouraged. I have a great staff at The Grove of other pastors and leaders.

How do you protect yourself, your time, and your family from the unique temptations that ministry families face?

I have four sons: a junior higher, a high schooler, and two in college so I feel like my time is always in demand. When my garage door opens at the end of the day when I come home, my cell phone goes off. I don’t take any calls on my cell phone over the weekend. I do not allow church emails to be forwarded to my home or to my phone. I only answer them in my office. And so, when I get home I want to be free of everything that happens at church. Another practical, simple thing I do is I take Fridays off. I like having Friday and Saturday back-to-back off, so all of my sermon prep work, all of our prep for Sunday as a staff is done on Thursday..

Your parents have been missionaries in Africa since 1970. How has their ministry influenced yours?

Lawrence Richard called it social learning theory. Just by being near people, you learn a lot. So just being around my dad and my mother, the first thing I learned was to live with great faith. When you spend 40 years in Africa, you realize quickly the only way you’re going to make it to the next day is to have a lot of faith and so I try to share that passion with the people that I lead and we talk a lot about faith. We take a lot of risk. I learned to take risk from my father and to not be afraid of failing.

How did growing up and then living in Africa inform your ministry perspective?

Growing up in Africa showed me how simple, and yet how powerful church can be. It doesn’t have to be about a staff and a building and payrolls. My church has a building so I’m a bit of a hypocrite, but we try to do it as simply as possible. To be honest, I think we have far too many ministries. I think we need to empower our people to meet each other’s needs, period, and stop paying so many people to do the things that people who call themselves Christians should be doing.

What influence is there from your training in intercultural studies?

We live in a globalized world and for me that’s an important part our church identity. I keep trying to tell our people that heaven is not just going to be filled with people like us. It’s going to be filled with people from every race and every tribe and every ethnicity. We can’t separate who we are as Christians from being a global people. I use that from my background to encourage people to live comfortably, to be moved towards people who are different in any way. I challenge our people that I speak to to include “the other” and to celebrate our differences, whether it be by language or skin color, or even denominations.

Is racial reconciliation formally a part of your ministry?

I haven’t termed it racial reconciliation. What we do at The Grove is racial celebration. We do all we can to make everything we do inclusive of the other and so we don’t want to be color blind. We want to celebrate those differences.

When I lived in Malawi, I got tired of doing funerals for babies who died of AIDS because their mothers had AIDS. I taught a class at a Christian university that I titled “A Theology of Suffering” that started with a Malawian perspective on suffering. I realized that this is the world’s common language, so it went from there.

A lot of times as Christians, we don’t have answers to life’s most difficult problems and to the problem of pain and we end up saying really cheap things like, “God will never give you more than you can handle.” That’s not even in the Bible, and the truth is we often end up in situations when on that week, for that moment, in that year, it feels like far more than anyone can handle and it is.

I talk about where God is and the things that happen in those dark times. I don’t want to oversimplify it, but there’s often a kind of spiritual change or growth that only happens on the most dark nights of our lives. If you think of anyone you would consider a mature Christian, I can almost promise you that person has been through some pain. God makes us deeper, wiser, more gentle people full of grace and mercy through it and we understand and we walk maybe a little closer to God.

Back home, Benjamin is sure he would be killed. His family is scattered across the eastern DR Congo, too afraid to return to their house but tired of living in limbo. Recently his daughter texted him, “Dad, I want to go back home. If they will kill me, let them kill me.”

Back home, Benjamin is sure he would be killed. His family is scattered across the eastern DR Congo, too afraid to return to their house but tired of living in limbo. Recently his daughter texted him, “Dad, I want to go back home. If they will kill me, let them kill me.”

Your new book,

Your new book,