Louisiana residents thankful for small miracles after Ida

The Rev. Luke Nguyen, right, celebrates Mass in a flood damaged parking lot in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida, Sunday, Sept. 5, 2021, in Jean Lafitte, La. The service was held in a parking lot after St. Anthony Catholic Church was flooded in the hurricane. (AP Photo/John Locher)

MARRERO, La. (AP) — Amid the devastation caused by Hurricane Ida, there was at least one bright light Sunday: Parishioners found that electricity had been restored to their church outside of New Orleans, a small improvement as residents of Louisiana struggle to regain some aspects of normal life.

In Jefferson Parish, the Rev. G. Amaldoss expected to celebrate Mass at St. Joachim Catholic Church in the parking lot, which was dotted with downed limbs. But when he swung open the doors of the church early Sunday, the sanctuary was bathed in light. That made an indoor service possible.

“Divine intervention,” Amaldoss said, pressing his hands together and looking toward the sky.

A week after Hurricane Ida struck, many in Louisiana continue to face food, water and gas shortages as well as power outages while battling heat and humidity. The storm was blamed for at least 17 deaths in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama.

On Sunday, state health officials announced that the death toll in Louisiana has climbed to 13, including a 74-year-old man who died of heat during an extensive power outage. In the Northeast, Ida’s remnants dumped record-breaking rain and killed at least 50 people from Virginia to Connecticut.

As Mass began Sunday, Amaldoss walked down the aisle of the church in his green robe, with just eight people spread among the pews. Instead, the seats brimmed with boxes of donated toothpaste, shampoo and canned vegetables.

“For all the people whose lives are saved and all the people whose lives are lost, we pray for them,” he said. “Remember the brothers and sisters driven by the wind and the water.”

Through the wall of windows behind the altar, beyond the swamp abutting the church, the floodgates that saved the building could be seen. The Gospel was the story of Jesus bringing sight to a blind man, and throughout the tiny church, stories of miracles were repeated.

Wynonia Lazaro gave thanks for newly restored power in her home, where the only casualties of Ida were some downed trees and loosened shingles.

“We are extremely blessed,” she said.

Some parishioners suffered total losses of their homes, or devastating damage. Gina Caulfield, a 64-year-old retired teacher, has been hopping from relative to relative after her cousin’s trailer, where she’d been living, was left uninhabitable. Still, she was grateful to have survived the storm.

“It’s a comfort to know we have people praying for us,” she said.

Some parishes outside New Orleans were battered for hours by winds of 100 mph (160 kph) or more, and Ida damaged or destroyed more than 22,000 power poles, more than hurricanes Katrina, Zeta and Delta combined.

More than 630,000 homes and businesses remained without power Sunday across southeast Louisiana, according to the state Public Service Commission. At the peak, 902,000 customers had lost power.

Fully restoring electricity to some places in the state’s southeast could take until the end of the month, according Phillip May, president and CEO of Entergy, which provides power to New Orleans and other areas in the storm’s path.

Entergy is in the process of acquiring air boats and other equipment needed to get power crews into swampy and marshy regions. May said many grocery stores, pharmacies and other businesses are a high priority.

“We will continue to work until every last light is on,” he said during a briefing Sunday.

In Jean Lafitte, a small town of about 2,000 people, pools of water along the roadway were receding and some of the thick mud left behind was beginning to dry.

Shannon Lation checks on her home destroyed by Hurricane Ida, Sunday, Sept. 5, 2021, in Lafitte, La. (AP Photo/John Locher)

At St. Anthony Church, the 4 feet (about 1.2 meters) of water once inside had seeped away, but a slippery layer of muck remained. Outside, the faithful sat on folding metal chairs under a blue tent to celebrate Mass. Next door, at the Piggly Wiggly, military police in fatigues stood guard.

“In times such like these, we come together and we help one another,” the Rev. Luke Nguyen, the church’s pastor, told a few dozen congregants.

Ronny Dufrene, a 39-year-old oil field worker from Lafayette, returned to his hometown to help.

“People are taking pictures of where their houses used to be,” he said. “But this is a chance to get together and praise God for what we do have, and that’s each other.”

In New Orleans, many churches remained closed due to lingering power outages.

But First Grace United Methodist Church opened its doors and held service without power. Sunlight from large windows brightened the sanctuary, where about 10 people sat.

“Whatever situation you’re in, you get to choose how you see it,” said Pastor Shawn Anglim, whose first time pastoring the congregation was after the church recovered from Hurricane Katrina 16 years ago. “You can see it from a place of faith, a place of hope and a place of love, and a place of possibility.”

Jennifer Moss, who attended service with her husband, Tom, said power had been restored to their home on Saturday.

“We’ve been blessed throughout this entire ordeal,” she said. “That storm could have been a little closer to the east, and we wouldn’t have a place to come and worship.”

In Lafitte, about 28 miles (45 kilometers) south of New Orleans, animal control officer Koby Bellanger experienced his own little blessing after he heard the sounds of an animal crying as he rode through the flooded streets with a sheriff’s deputy.

Bellanger waded through the water and found a tiny, green-eyed black kitten clinging to the engine of a car outside a devastated house. He hoisted the animal up, to the delight of Lafayette Parish Deputy Rebecca Bobzin.

“Bring him!” Bobzin screamed in delight.

Louisiana’s 13 storm-related deaths included five nursing home residents evacuated ahead of the hurricane along with hundreds of other seniors to a warehouse in Louisiana, where health officials said conditions became unsafe. On Saturday, State Health Officer Dr. Joseph Kanter ordered the immediate closure of the seven nursing facilities that sent residents to the warehouse.

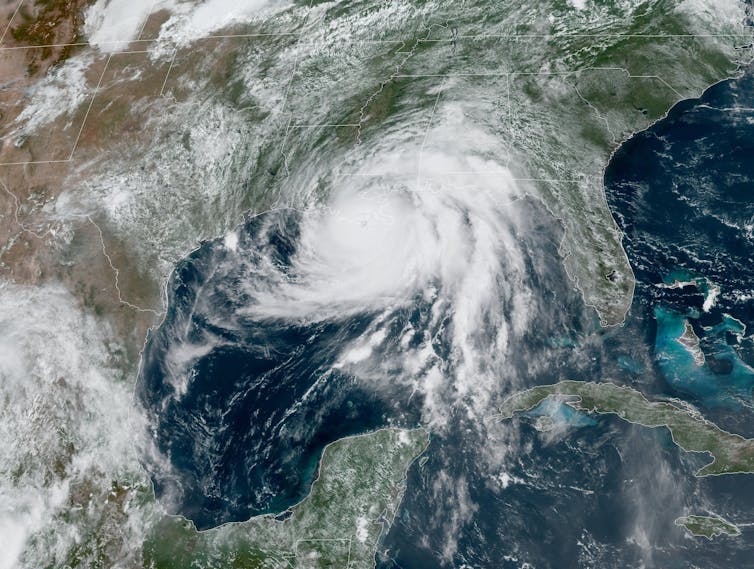

Edwards was briefed Sunday about a cluster of thunderstorms near Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, but said forecasters “don’t see much potential at all for it developing into a storm of any real significance and we’re very, very thankful for that.”

He said it does have the potential to bring some rain to coastal Louisiana and southeast Louisiana.

___

Morrison reported from New Orleans. Associated Press writer Denise Lavoie in Richmond, Virginia, contributed.