by Phil Galewitz, Kaiser Health News | Jul 2, 2021 | Headline News, Social Justice |

PHILADELPHIA — When doctors at a primary care clinic here noticed many of its poorest patients were failing to show up for appointments, they hoped giving out free rides would help.

But the one-time complimentary ride didn’t reduce these patients’ 36% no-show rate at the University of Pennsylvania Health System clinics.

“I was super surprised it did not have any effect,” said Dr. Krisda Chaiyachati, the Penn researcher who led the 2018 study of 786 Medicaid patients.

Many of the patients did not take advantage of the ride because they were either saving it for a more important medical appointment or preferred their regular travel method, such as catching a ride from a friend, a subsequent study found.

It was not the first time that efforts by a health care provider to address patients’ social needs — such as food, housing and transportation — failed to work.

In the past decade, dozens of studies funded by state and federal governments, private hospitals, insurers and philanthropic organizations have looked into whether addressing patients’ social needs improves health and lowers medical costs.

But so far it’s unclear which of these strategies, focused on so-called social determinants of health, are most effective or feasible, according to several recent academic reports by experts at Columbia, Duke and the University of California-San Francisco that evaluated existing research.

And even when such interventions show promising results, they usually serve only a small number of patients. Another challenge is that several studies did not go on long enough to detect an impact, or they did not evaluate health outcomes or health costs.

“We are probably at a peak of inflated expectations, and it is incumbent on us to find the innovations that really work,” said Dr. Laura Gottlieb, director of the UCSF Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network. “Yes, there’s a lot of hype, and not all of these interventions will have staying power.”

With health care providers and insurers eager to find ways to lower costs, the limited success of social-need interventions has done little to slow the surge of pilot programs — fueled by billions of private and government dollars.

Paying for Health, Not Just Health Care

Across the country, both public and private health insurance programs are launching large initiatives aimed at improving health by helping patients with unmet social needs. One of the biggest efforts kicks off next year in North Carolina, which is spending $650 million over five years to test the effect of giving Medicaid enrollees assistance with housing, food and transportation.

California is redesigning its Medicaid program, which covers nearly 14 million residents, to dramatically increase social services to enrollees.

These moves mark a major turning point for Medicaid, which, since its inception in 1965, largely has prohibited government spending on most nonmedical services. To get around this, states have in recent years sought waivers from the federal government and pushed private Medicaid health plans to address enrollees’ social needs.

The move to address social needs is gaining steam nationally because, after nearly a dozen years focused on expanding insurance under the Affordable Care Act, many experts and policymakers agree that simply increasing access to health care is not nearly enough to improve patients’ health.

That’s because people don’t just need access to doctors, hospitals and drugs to be healthy, they also need healthy homes, healthy food, adequate transportation and education, a steady income, safe neighborhoods and a home life free from domestic violence — things hospitals and doctors can’t provide, but that in the long run are as meaningful as an antibiotic or an annual physical.

Researchers have known for decades that social problems such as unstable housing and lack of access to healthy foods can significantly affect a patient’s health, but efforts by the health industry to take on these challenges didn’t really take off until 2010 with the passage of the ACA. The law spurred changes in how insurers pay health providers — moving them away from receiving a set fee for each service to payments based on value and patient outcomes.

As a result, hospitals now have a financial incentive to help patients with nonclinical problems — such as housing and food insecurity — that can affect health.

Temple University Health System in Philadelphia launched a two-year program last year to help 25 homeless Medicaid patients who frequently use its emergency room and other ERs in the city by providing them free housing, and caseworkers to help them access other health and social services. It helps them furnish their apartments, connects them to healthy delivered meals and assists with applications for income assistance such as Social Security.

To qualify, participants had to have used the ER at least four times in the previous year and had at least $10,000 in medical claims that year.

Temple has seen promising results when comparing patients’ experiences before the study to the first five months they were all housed. In that time, the participants’ average number of monthly ER visits fell 75% and inpatient hospital admissions dropped 79%.

At the same time, their use of outpatient services jumped by 50% — an indication that patients are seeking more appropriate and lower-cost settings for care.

Living Life as ‘Normal People Do’

One participant is Rita Stewart, 53, who now lives in a one-bedroom apartment in Philadelphia’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood, home to many college students and young families.

“Everyone knows everyone,” Stewart said excitedly from her second-floor walk-up. It’s “a very calm area, clean environment. And I really like it.”

Before joining the Temple program in July and getting housing assistance, Stewart was living in a substance abuse recovery home. She had spent a few years bouncing among friends’ homes and other recovery centers. Once she slept in the city bus terminal.

In 2019, Stewart had visited the Temple ER four times for various health concerns, including anxiety, a heart condition and flu.

Stewart meets with her caseworkers at least once a week for help scheduling doctor appointments, arranging group counseling sessions and managing household needs.

“It’s a blessing,” she said from her apartment with its small kitchen and comfy couch.

“I have peace of mind that I am able to walk into my own place, leave when I want to, sleep when I want to,” Stewart said. “I love my privacy. I just look around and just wow. I am grateful.”

Stewart has sometimes worked as a nursing assistant and has gotten her health care through Medicaid for years. She still deals with depression, she said, but having her own home has improved her mood. And the program has helped keep her out of the hospital.

“This is a chance for me to take care of myself better,” she said.

Her housing assistance help is set to end next year when the Temple program ends, but administrators said they hope to find all the participants permanent housing and jobs.

“Hopefully that will work out and I can just live my life like normal people do and take care of my priorities and take care of my bills and things that a normal person would do,” Stewart said.

“Housing is the second-most impactful social determinant of health after food security,” said Steven Carson, a senior vice president at Temple University Health System. “Our goal is to help them bring meaningful and lasting health improvement to their lives.”

Success Doesn’t Come Cheap

Temple is helping pay for the program; other funding comes from two Medicaid health plans, a state grant and a Pittsburgh-based foundation. A nonprofit human services organization helps operate the program.

Program organizers hope the positive results will attract additional financing so they can expand to help many more homeless patients.

The effort is expensive. The “Housing Smart” program cost $700,000 to help 25 people for one year, or $28,000 per person. To put this in perspective, a single ER visit can cost a couple of thousands of dollars. And “frequent flyer” patients can tally up many times that in ER visits and follow-up care.

If Temple wants to help dozens more patients with housing, it will need tens of millions of dollars more per year.

Still, Temple officials said they expect the effort will save money over the long run by reducing expensive hospital visits — but they don’t yet have the data to prove that.

The Temple program was partly inspired by a similar housing effort started at two Duke University clinics in Durham, North Carolina. That program, launched in 2016, has served 45 patients with unstable housing and has reduced their ER use. But it’s been unable to grow because housing funding remains limited. And without data showing the intervention saves on health care costs, the organizers have been unable to attract more financing.

Often there is a need to demonstrate an overall reduction in health care spending to attract Medicaid funding.

“We know homelessness is bad for your health, but we are in the early stages of knowing how to address it,” said Dr. Seth Berkowitz, a researcher at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

Results Remain to Be Seen

“We need to pay for health not just health care,” said Elena Marks, CEO of the Houston-based Episcopal Health Foundation, which provides grants to community clinics and organizations to help address the social needs of vulnerable populations.

The nationwide push to spend more on social services is driven first by the recognition that social and economic forces have a greater impact on health than do clinical services like doctor visits, Marks said. A second factor is that the U.S. spends far less on social services per capita compared with other large, industrialized nations.

“This is a new and emerging field,” Marks said when reviewing the evaluations of the many social determinants of health studies. “The evidence is weak for some, mixed for some, and strong for a few areas.”

But despite incomplete evidence, Marks said, the status quo isn’t working either: Americans generally have poorer health than their counterparts in other industrialized countries with more robust social services.

“At some point we keep paying you more and more, Mr. Hospital, and people keep getting less and less. So, let’s go look for some other solutions” Marks said.

The covid-19 pandemic has shined further light on the inequities in access to health services and sparked interest in Medicaid programs to address social issues. Over half of states are implementing or expanding Medicaid programs that address social needs, according to a KFF study in October 2020. (The KHN newsroom is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

The Medicaid interventions are not intense in many states: Often they involve simply screening patients for social needs problems or referring them to another agency for help. Only two states — Arizona and Oregon — require their Medicaid health plans to directly invest money into pilot programs to address the social problems that screening reveals, according to a survey by consulting firm Manatt.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which is funding a growing number of efforts to help Medicaid patients with social needs, said it “remains committed” to helping states meet enrollees’ social challenges including education, employment and housing.

On Jan. 7, CMS officials under the Trump administration sent guidance to states to accelerate these interventions. In May, under President Joe Biden, a CMS spokesperson told KHN: “Evidence indicates that some social interventions targeted at Medicaid and CHIP beneficiaries can result in improved health outcomes and significant savings to the health care sector.”

The agency cited a 2017 survey of 17 state Medicaid directors in which most reported they recognized the importance of social determinants of health. The directors also noted barriers to address them, such as cost and sustainability.

In Philadelphia, Temple officials now face the challenge of finding new financing to keep their housing program going.

“We are trying to find the magic sauce to keep this program running,” said Patrick Vulgamore, project manager for Temple’s Center for Population Health.

Sojourner Ahebee, health equity fellow at WHYY’s health and science show, “The Pulse,” contributed to this report.

This story is part of a partnership that includes WHYY, NPR and KHN.

Subscribe to KHN's free Morning Briefing.

by Carrie Antlfinger, AP | Jun 25, 2021 | Commentary, Headline News |

In this May 9, 2021, photo, Rev. Joseph Jackson Jr. talks to his congregation at Friendship Missionary Baptist Church in Milwaukee during a service. He is president of the board of directors for Milwaukee Inner City Congregations Allied for Hope, which along with Pastors United, Souls to the Polls and the local health clinic Health Connections, is working to get vaccination clinics into churches to help vaccinate the Black community. He’s also been urging his congregation during Sunday services to get vaccinated. (AP Photo/Carrie Antlfinger)

MILWAUKEE (AP) — Every Sunday at Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, the Rev. Joseph Jackson Jr. praises the Lord before his congregation. But since last fall he’s been praising something else his Black community needs: the COVID-19 vaccine.

“We want to continue to encourage our people to get out, get your shots. I got both of mine,” Jackson said to applause at the church in Milwaukee on a recent Sunday.

Members of Black communities across the U.S. have disproportionately fallen sick or died from the virus, so some church leaders are using their influence and trusted reputations to fight back by preaching from the pulpit, phoning people to encourage vaccinations, and hosting testing clinics and vaccination events in church buildings.

Some want to extend their efforts beyond the fight against COVID-19 and give their flocks a place to seek health care for other ailments at a place they trust — the church.

In this May 9, 2021, photo, Rev. Joseph Jackson Jr. talks to his congregation at Friendship Missionary Baptist Church in Milwaukee during a service. He is president of the board of directors for Milwaukee Inner City Congregations Allied for Hope, which along with Pastors United, Souls to the Polls and the local health clinic Health Connections is working to get vaccination clinics into churches to help vaccinate the Black community. He’s also been urging his congregation during Sunday services to get vaccinated. (AP Photo/Carrie Antlfinger)

“We can’t go back to normal because we died in our normal,” Debra Fraser-Howze, the founder of Choose Healthy Life, told The Associated Press. “We have health disparities that were so serious that one pandemic virtually wiped us out more than anybody else. We can’t allow for that to happen again.”

Choose Healthy Life, a national initiative involving Black clergy, United Way of New York City and others, has been awarded a $9.9 million U.S. Department of Health and Human Services grant to expand vaccinations and and make permanent the “health navigators” who are already doing coronavirus testing and vaccinations in churches.

The navigators will eventually bring in experts for vaccinations, such as the flu, and to screen for ailments that are common in Black communities, including heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, AIDS and asthma. The effort aims to reduce discomfort within Black communities about seeking health care, either due to concerns about racism or a historical distrust of science and government.

The initiative has so far been responsible for over 30,000 vaccinations in the first three months in 50 churches in New York; Newark, New Jersey; Detroit; Washington, D.C.; and Atlanta.

The federal funding will expand the group’s effort to 100 churches, including in rural areas, in 13 states and the District of Columbia, and will help establish an infrastructure for the health navigators to start screenings. Quest Diagnostics and its foundation has already provided funding and testing help.

Choose Healthy Life expects to be involved for at least five years, after which organizers hope control and funding will be handled locally, possibly by health departments or in alignment with federally supported health centers, Fraser-Howze said.

The initiative is also planning to host seminars in churches on common health issues. Some churches already have health clinics and they hope that encourages other churches to follow suit, said Fraser-Howze, who led the National Black Leadership Commission on AIDS for 21 years.

FILE – In this file photo taken June 6, 2021, first lady Jill Biden, center left, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Choose Healthy Life public health navigator Linda Thompson and Choose Healthy Life Founder Debra Fraser-Howze, far right, speak to a person as they visit a vaccine clinic at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in the Harlem neighborhood of New York. The church is part of Choose Healthy Life, a national initiative involving Black clergy, United Way of New York City and others, that has just been awarded a $9.9 million U.S. Department of Health and Human Services grant to expand vaccinations and provide screening and other health services in churches. (AP Photo/Craig Ruttle, File)

“The Black church is going to have to be that link between faith and science,” she said.

In Milwaukee, nearly 43% of all coronavirus-related deaths have been in the Black community, according to the Milwaukee Health Department. Census data indicates Blacks make up about 39% of the city’s population. An initiative involving Pastors United, Milwaukee Inner City Congregations Allied for Hope and Souls to the Polls has provided vaccinations in at least 80 churches there already.

Milwaukee is one of the most segregated cities in the country, according to the studies by the Brookings Institution. Ericka Sinclair, CEO of Health Connections, Inc., which administers vaccinations, says that’s why putting vaccination centers in churches and other trusted locations is so important.

“Access to services is not the same for everyone. It’s just not. And it is just another reason why when we talk about health equity, we have … to do a course correction,” she said.

She’s also working to get more community health workers funded through insurance companies, including Medicaid.

The church vaccination effort involved Milwaukee Inner City Congregations Allied for Hope, which is faith organization working on social issues. Executive Director and Lead Organizer Lisa Jones says the effect of COVID-19 on the Black community has reinforced the need to address race-related disparities in health care. The group has hired another organizer to address disparities in hospital services in the inner city and housing, and lead contamination.

At a recent vaccination clinic in Milwaukee at St. Matthew, a Christian Methodist Episcopal church, Melanie Paige overcame her fears to get vaccinated. Paige, who has lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, said the church clinic helped motivate her, along with encouragement from her son.

“I was more comfortable because I belong to the church and I know I’ve been here all my life. So that made it easier.”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

by Cara Anthony, a Kaiser Health News Midwest correspondent | Oct 17, 2019 | Headline News |

While living in Detroit earlier this year, Brianna Snitchler wanted a cyst removed from her abdomen. But her doctor wanted the growth checked for cancer first. (Callie Richmond for KHN)

Brianna Snitchler was just figuring out the art of adulting when she scheduled a biopsy at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Snitchler was on top of her finances: Her student loan balance was down and her credit score was up.

“I had been working for the past three years trying to improve my credit and, you know, just become a functioning adult human being,” Snitchler, 27, said.

For the first time in her adult life, she had health insurance through her job and a primary care doctor she liked. Together they were working on Snitchler’s concerns about her mental and physical health.

One concern was a cyst on her abdomen. The growth was about the size of a quarter, and it didn’t hurt or particularly worry Snitchler. But it did make her self-conscious whenever she went for a swim.

“People would always call it out and be alarmed by it,” she recalled.

Before having the cyst removed, Snitchler’s doctor wanted to check the growth for cancer. After a first round of screening tests, Snitchler had an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy at Henry Ford Health System’s main hospital.

The procedure was “uneventful,” with no complications reported, according to results faxed to her primary care doctor after the procedure. The growth was indeed benign, and Snitchler thought her next step would be getting the cyst removed.

Then the bill came.

The Patient: Brianna Snitchler, 27, a user-experience designer living in Detroit at the time. As a contractor for Ford Motor Co., she had a UnitedHealthcare insurance plan.

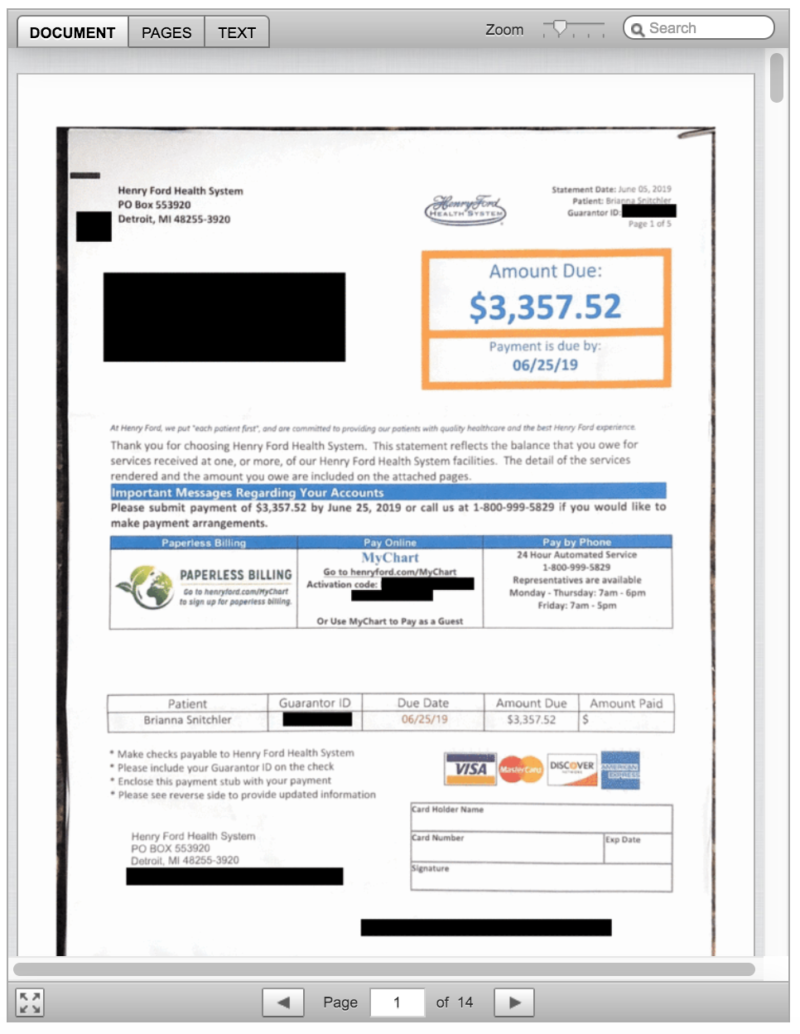

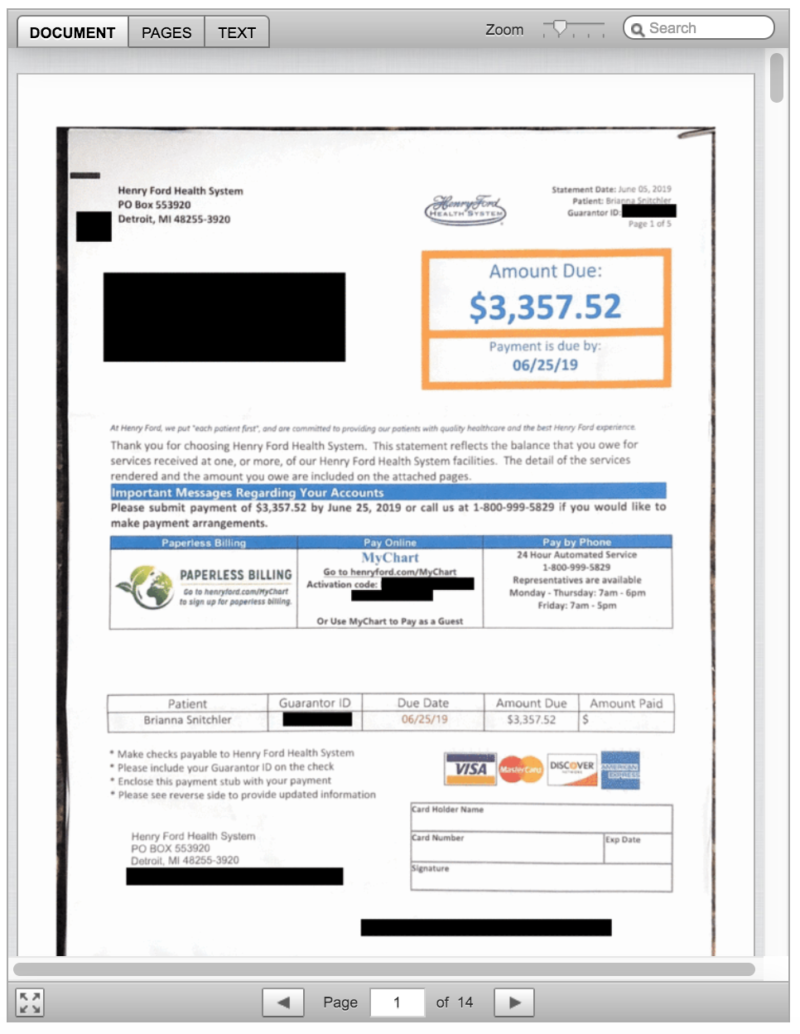

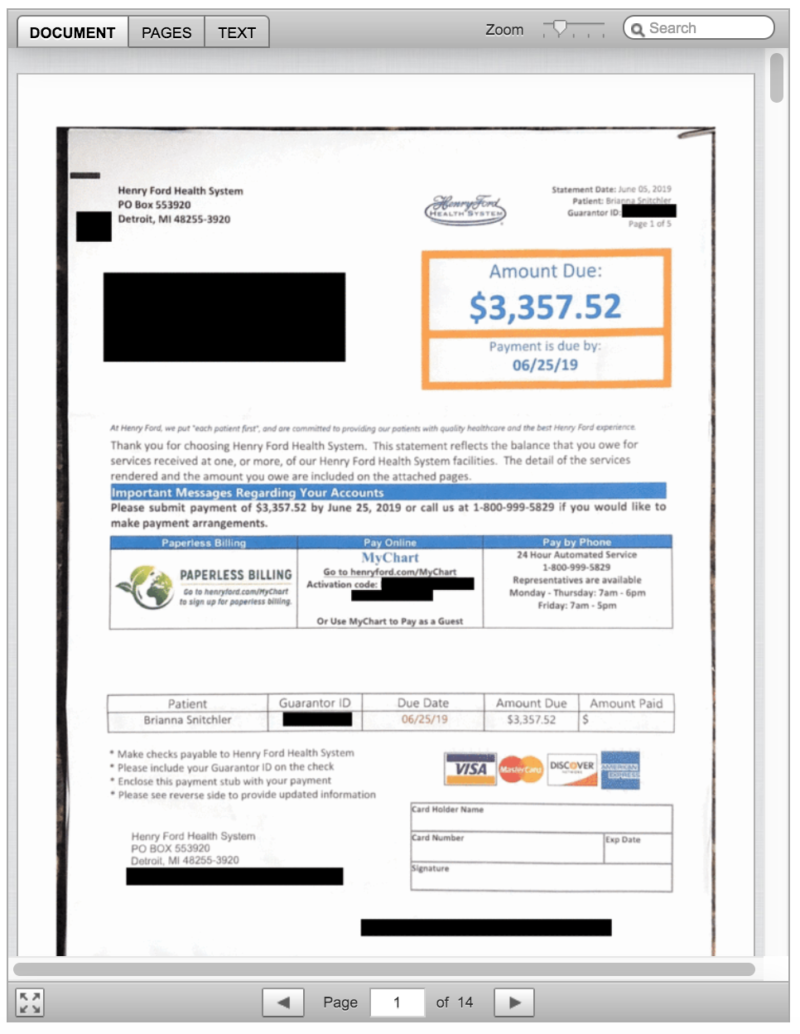

Total Bill: $3,357.52, including a $2,170 facility fee listed as “operating room services.” The balance included a biopsy, ultrasound, physician charges and lab tests.

Service Provider: Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Medical Procedure: Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of a cyst.

What Gives: When Snitchler scheduled the biopsy, no one told her that Henry Ford Health System would also charge her a $2,170 facility fee.

Snitchler said the bill turned out to be far more than what she budgeted for. Her insurance plan from UnitedHealthcare had a high-deductible of $3,250, plus she would owe coinsurance. All told, her bills for the care she received related to the biopsy left her on the hook for $3,357.52, with her insurance paying $974.

“She shrugged it off,” Snitchler’s partner, Emi Aguilar, recalled. “But I could see that she was upset in her eyes.”

Snitchler panicked when she realized the bill threatened the couple’s financial security. Snitchler had already spent down her savings for a recent cross-country move to Austin, Texas.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman David Olejarz said the “procedure was performed in the Interventional Radiology procedure room, where the imaging allows the biopsy to be much more precise.”

“We perform procedures in the most appropriate venue to ensure the highest standards of patient quality and safety,” Olejarz wrote.

The initial bill from Henry Ford referred to “operating room services.” The hospital later sent an itemized bill that referred to the charge for a treatment room in the radiology department. Both descriptions boil down to a facility fee, a common charge that has become controversial as hospitals search for additional streams of income, and as more patients complain they’ve been blindsided by these fees.

Hospital officials argue that medical centers need the boosted income to provide the expensive care sick patients require, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

But the way hospitals calculate facility fees is “a black box,” said Ted Doolittle, with the Office of the Healthcare Advocate for Connecticut, a state that has put a spotlight on the issue.

“It’s somewhat akin to a cover charge” at a club, said Doolittle, who previously served as deputy director of the federal Center for Program Integrity at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Hospitals in Connecticut billed more than $1 billion in facility fees in 2015 and 2016, according to state records. In 2015, Connecticut lawmakers approved a bill that forces all hospitals and medical providers to disclose facility fees upfront. Now patients in Connecticut “should never be charged a facility fee without being shown in burning scarlet letters that they are going to get charged this fee,” Doolittle said.

In Michigan, there’s no law requiring hospitals and other providers of health care services to inform patients of facility fees ahead of time.

Brianna Snitchler’s procedure took place on campus at Henry Ford’s main hospital site. When she got her bill, with its mention of “operating room services,” she was baffled. Snitchler said the room had “crazy medical equipment,” but she was still in her street clothes as a nurse numbed her cyst and she was sent home in a matter of minutes.

With Snitchler’s permission, Kaiser Health News shared her itemized bill, biopsy results and explanation of benefits with Dr. Mark Weiss, a radiologist who leads MediCrew, a company in Flint, Mich., that helps patients navigate the health system.

Weiss said it probably wasn’t medically necessary for Snitchler to go to the hospital to receive good care. “Not all surgical procedures have to be done at a surgical center,” he said, noting that biopsies often can be done in an office-based treatment center.

Resolution: Hoping for a reasonable explanation — or even the discovery of a mistake — Snitchler called her insurance company and the hospital.

A representative at Henry Ford told her on the phone that the hospital isn’t “legally required” to inform patients of fees ahead of time.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman Olejarz apologized for that response: “We’ll use it as a teachable moment for our staff. We are committed to being transparent with our patients about what we charge.”

He pointed to an initiative launched in 2018 that helps patients anticipate out-of-pocket expenses. The program targets the most common elective radiology and gastroenterology tests that often have high price tags for patients.

Asked if Snitchler’s ultrasound-guided needle biopsy will be included in the price transparency initiative, Olejarz replied, “Can’t say at this point.”

In addition to the pilot program to inform patients of fees, Olejarz said, the hospital also plans to roll out an online cost-estimator tool.

For now, Snitchler has decided not to get the cyst removed, and she plans to try to negotiate on her bill. She has not yet paid any portion of it.

“You should always negotiate; you should always try,” Doolittle said. “Doesn’t mean it’s going to work, but it can work. People should not be shy about it.”

“We are happy to work out a flexible payment plan that best meets her needs,” Olejarz wrote when Kaiser Health News first inquired about Snitchler’s bill.

The Takeaway: When your doctor recommends an outpatient test or procedure like a biopsy, be aware that the hospital may be the most expensive place you can have it done. Ask your physician for recommendations of where else you might have the procedure, and then call each facility to try to get an estimate of the costs you’d face.

Also, be wary of places that may look like independent doctor’s offices but are owned by a hospital. These practices also can tack hefty facility fees onto your bill.

If you get a bill that seems inflated, call your hospital and insurer and try to negotiate it down.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

by Cara Anthony, a Kaiser Health News Midwest correspondent | Oct 16, 2019 | Headline News |

While living in Detroit earlier this year, Brianna Snitchler wanted a cyst removed from her abdomen. But her doctor wanted the growth checked for cancer first. (Callie Richmond for KHN)

Brianna Snitchler was just figuring out the art of adulting when she scheduled a biopsy at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Snitchler was on top of her finances: Her student loan balance was down and her credit score was up.

“I had been working for the past three years trying to improve my credit and, you know, just become a functioning adult human being,” Snitchler, 27, said.

For the first time in her adult life, she had health insurance through her job and a primary care doctor she liked. Together they were working on Snitchler’s concerns about her mental and physical health.

One concern was a cyst on her abdomen. The growth was about the size of a quarter, and it didn’t hurt or particularly worry Snitchler. But it did make her self-conscious whenever she went for a swim.

“People would always call it out and be alarmed by it,” she recalled.

Before having the cyst removed, Snitchler’s doctor wanted to check the growth for cancer. After a first round of screening tests, Snitchler had an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy at Henry Ford Health System’s main hospital.

The procedure was “uneventful,” with no complications reported, according to results faxed to her primary care doctor after the procedure. The growth was indeed benign, and Snitchler thought her next step would be getting the cyst removed.

Then the bill came.

The Patient: Brianna Snitchler, 27, a user-experience designer living in Detroit at the time. As a contractor for Ford Motor Co., she had a UnitedHealthcare insurance plan.

Total Bill: $3,357.52, including a $2,170 facility fee listed as “operating room services.” The balance included a biopsy, ultrasound, physician charges and lab tests.

Service Provider: Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Medical Procedure: Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of a cyst.

What Gives: When Snitchler scheduled the biopsy, no one told her that Henry Ford Health System would also charge her a $2,170 facility fee.

Snitchler said the bill turned out to be far more than what she budgeted for. Her insurance plan from UnitedHealthcare had a high-deductible of $3,250, plus she would owe coinsurance. All told, her bills for the care she received related to the biopsy left her on the hook for $3,357.52, with her insurance paying $974.

“She shrugged it off,” Snitchler’s partner, Emi Aguilar, recalled. “But I could see that she was upset in her eyes.”

Snitchler panicked when she realized the bill threatened the couple’s financial security. Snitchler had already spent down her savings for a recent cross-country move to Austin, Texas.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman David Olejarz said the “procedure was performed in the Interventional Radiology procedure room, where the imaging allows the biopsy to be much more precise.”

“We perform procedures in the most appropriate venue to ensure the highest standards of patient quality and safety,” Olejarz wrote.

The initial bill from Henry Ford referred to “operating room services.” The hospital later sent an itemized bill that referred to the charge for a treatment room in the radiology department. Both descriptions boil down to a facility fee, a common charge that has become controversial as hospitals search for additional streams of income, and as more patients complain they’ve been blindsided by these fees.

Hospital officials argue that medical centers need the boosted income to provide the expensive care sick patients require, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

But the way hospitals calculate facility fees is “a black box,” said Ted Doolittle, with the Office of the Healthcare Advocate for Connecticut, a state that has put a spotlight on the issue.

“It’s somewhat akin to a cover charge” at a club, said Doolittle, who previously served as deputy director of the federal Center for Program Integrity at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Hospitals in Connecticut billed more than $1 billion in facility fees in 2015 and 2016, according to state records. In 2015, Connecticut lawmakers approved a bill that forces all hospitals and medical providers to disclose facility fees upfront. Now patients in Connecticut “should never be charged a facility fee without being shown in burning scarlet letters that they are going to get charged this fee,” Doolittle said.

In Michigan, there’s no law requiring hospitals and other providers of health care services to inform patients of facility fees ahead of time.

Brianna Snitchler’s procedure took place on campus at Henry Ford’s main hospital site. When she got her bill, with its mention of “operating room services,” she was baffled. Snitchler said the room had “crazy medical equipment,” but she was still in her street clothes as a nurse numbed her cyst and she was sent home in a matter of minutes.

With Snitchler’s permission, Kaiser Health News shared her itemized bill, biopsy results and explanation of benefits with Dr. Mark Weiss, a radiologist who leads MediCrew, a company in Flint, Mich., that helps patients navigate the health system.

Weiss said it probably wasn’t medically necessary for Snitchler to go to the hospital to receive good care. “Not all surgical procedures have to be done at a surgical center,” he said, noting that biopsies often can be done in an office-based treatment center.

Resolution: Hoping for a reasonable explanation — or even the discovery of a mistake — Snitchler called her insurance company and the hospital.

A representative at Henry Ford told her on the phone that the hospital isn’t “legally required” to inform patients of fees ahead of time.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman Olejarz apologized for that response: “We’ll use it as a teachable moment for our staff. We are committed to being transparent with our patients about what we charge.”

He pointed to an initiative launched in 2018 that helps patients anticipate out-of-pocket expenses. The program targets the most common elective radiology and gastroenterology tests that often have high price tags for patients.

Asked if Snitchler’s ultrasound-guided needle biopsy will be included in the price transparency initiative, Olejarz replied, “Can’t say at this point.”

In addition to the pilot program to inform patients of fees, Olejarz said, the hospital also plans to roll out an online cost-estimator tool.

For now, Snitchler has decided not to get the cyst removed, and she plans to try to negotiate on her bill. She has not yet paid any portion of it.

“You should always negotiate; you should always try,” Doolittle said. “Doesn’t mean it’s going to work, but it can work. People should not be shy about it.”

“We are happy to work out a flexible payment plan that best meets her needs,” Olejarz wrote when Kaiser Health News first inquired about Snitchler’s bill.

The Takeaway: When your doctor recommends an outpatient test or procedure like a biopsy, be aware that the hospital may be the most expensive place you can have it done. Ask your physician for recommendations of where else you might have the procedure, and then call each facility to try to get an estimate of the costs you’d face.

Also, be wary of places that may look like independent doctor’s offices but are owned by a hospital. These practices also can tack hefty facility fees onto your bill.

If you get a bill that seems inflated, call your hospital and insurer and try to negotiate it down.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

by Wil LaVeist | Jul 18, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

“Do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit, who is in you, whom you have received from God? You are not your own…. Therefore honor God with your body.” 1 Cor. 6:19-20

It is well known that blacks live sicker and die younger than any other racial group. Look no farther than the church with the pastor battling hypertension and diabetes or the congregation with several obese members sitting in the pews. It would seem that the black church in America would be the leading ally supporting the nation’s first black president in the debate over access to affordable healthcare. It would seem that the black church would lead the way toward healthier eating and living.

Could it be that black church culture is leading us astray?

I thought about this during a recent conference in Baltimore on black global health. The International Conference on Health in the African Diaspora, hosted by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Disparities Solutions, brought together healthcare professionals and researchers, from across the Western Hemisphere to discuss common health problems among the descendants of African slaves. Black Arts Movement icon Sonia Sanchez set the tone as the keynote speaker July 4, inspiring the crowd with a special poem for the occasion. The award-winning author participated throughout the weeklong conference.

Listening to a sister from Brazil and a brother from Peru discuss high rates of obesity, diabetes, infant deaths and the spread of HIV/AIDS among blacks in their countries sounded like the health crisis of black New York, Chicago, or the Mississippi Delta. Modern racism and the legacy of slavery haunt all of us. Participants also shared solutions and pledged to work together. In fact, according to Dr. Thomas LaVeist, a book and curriculum addressing these health themes are being created for the public and for high school and college educators. Thomas, who happens to be my brother, directs the Hopkins center and is the mastermind behind the conference, which is scheduled to take place every two years.

Solutions are basically what government and institutions can do to end racism and ensure all people have access to quality affordable healthcare and what blacks can do themselves to care for their “temples of the Holy Spirit.”

The black church should be more outspoken in support of increased access to quality affordable care. Our cousins from Canada and Central and South America, who for the most part receive varying degrees well-executed and poorly-executed universal healthcare, are puzzled as to why we richer Americans are debating what the rest of the industrialized world has long settled — that healthcare access is a God-given human right, not a privilege to be determined by profit-seeking private insurance companies.

After the conference, Thomas told me that the Catholic Church (obviously many Catholics are also black) has been the most vocal Christians on healthcare, mainly around the debate on whether Catholic organizations should be mandated to support abortions for employees (some evangelical Protestant organizations have recently joined that fight, too). Thomas suggested the traditional black church denominations could find their unified voice by calling for all Americans to be insured (Obama’s Affordable Care Act would still leave 20 million people uninsured). However, regardless of what the government does, black churches should lead by example with healthier eating and living, he said.

BAD FOR THE SOUL? Black churches are routinely feeding their people unhealthy soul food staples such as fried chicken and macaroni and cheese. Is that biblical?

“Black church culture is out of alignment with some biblical teachings, particularly when it comes to how we eat,” my brother said. “Church culture has got us drinking Kool-Aid, eating white bread, fried chicken, large servings of macaroni and cheese and collard greens drenched with salty hog maws (foods that are high in sugar, salt, calories, and carbohydrates that trigger health problems). We’re eating this in the church basement at dinner and at church conventions! Meanwhile, the Bible teaches against gluttony.”

Don’t judge or condemn those who are obese, but encourage and show everyone how to eat healthy, Thomas added. He cited Pastor Michael Minor of Oak Hill Baptist Church in the Mississippi Delta as pushing the healthy eating message that all black churches should adopt. The Delta is one of America’s poorest areas and leads the nation in obesity, diabetes, and heart disease rates. In 2011, Pastor Minor, known as “the Southern pastor who banned fried chicken in his church,” banished all unhealthy foods and insisted soul food meals be prepared in healthier ways; many of his members are losing weight and improving their overall health. Other churches across the country such as, First Baptist Church of Glenarden in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, are on similar missions.

Ask yourself, when it comes to health, what is the black church best known for?

What might the state of black health in America (and the African diaspora) be if your answer was healthy eating and living?