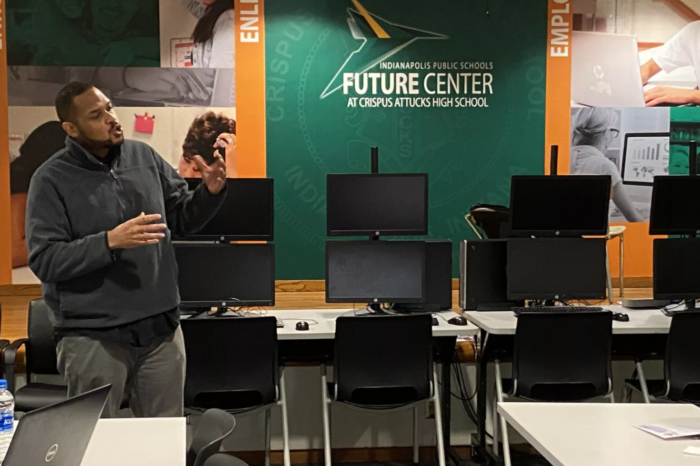

Early Learning Director Kahlil Mwaafrika gives a presentation at Crispus Attucks High School. Provided by Blake Nathan

After teaching for more than 20 years, Kahlil Mwaafrika said he’s used to being an anomaly in urban Indianapolis schools. As an adjunct professor of early childhood education at IUPUI, only a handful of his hundreds of students are Black men.

“There’s very few people who look like me in buildings,” he said.

So in early 2018, he started working on a program to recruit, train, and place Black men as Indianapolis preschool teachers.

Mwaafrika brought his idea to Blake Nathan, CEO of the Educate ME Foundation, an organization that works to diversify the national teaching population by recruiting and retaining educators of color. Earlier this year, Mwaafrika and Nathan formed the idea into a program called Educate ME Early and partnered with Early Learning Indiana to create 50 two-year fellowships for men of color.

They hope to address the barriers that discourage men of color from working as preschool teachers, including a lack of representation in preschool classrooms and the misconception that teaching preschool is like a babysitting job.

Early Learning Indiana is providing funding for Educate ME to give fellows up to $1,000 in stipends throughout the two-year commitment. Once the fellows complete training and begin working, they’ll be paid $10-14 per hour. Educate ME will place fellows at Early Learning Indiana’s nine child care centers before staffing other sites.

Brittany Krier, chief strategy officer for Early Learning Indiana, said early learning teachers have an “unparalleled opportunity for impact” by working with students in the most formative years of their lives. The organization has been looking to diversify educators while trying to recruit more preschool teachers in general.

“As a field, we have some work to do to welcome more men, and more men of color, into the profession overall,” Krier said. She views this program as a starting point in the push to make Indiana teachers more reflective of their students.

It’s not clear how many Indianapolis preschool teachers are Black, since the state doesn’t track that data. But among full-time K-12 educators statewide, almost 93% are white, according to the state’s education department. Nearly 30% of students in Indiana are people of color, however, creating a disconnect in representation.

In early childhood education, 36% of the nationwide workforce are people of color. In Indiana, that number drops to 14%, according to a press release from Early Learning Indiana. Of Indiana’s some 30,000 early childhood educators, 7% are men.

This poses a challenge for both students and people of color, especially men, who are considering becoming teachers.

“It’s difficult to recruit young Black men if they don’t see themselves represented in the field,” Nathan said.

Preschool teacher Zachary Ferguson has been working at Day Early Learning in Fort Harrison for eight years. Of his 20 co-workers, only one is a man. He advises Black men who might be hesitant about entering the field to “take a chance.”

“I think we just have to strive to do better for our kids,” Ferguson said.

Becoming an early learning educator in Indiana requires much less training than for other grade levels, Mwaafrika said, making it easier to enter the field. But this also contributes to a stigma that can discourage people from considering early childhood education as a career.

Nathan said people often view it as a babysitting job. He hopes this program will help show people the benefits of working with children and the impact they can make. If a Black student has at least one Black teacher in grades three, four, or five, they are more likely to graduate high school, according to a 2017 study by the IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

Black educators can influence students of other ethnicities as well by “opening their cultural lenses,” Nathan said.

“Other races need to see African American teachers in the classroom that are well-educated and very competent in their instruction,” he said.

The Educate ME Early fellows start with an orientation through Early Learning Indiana and a state-required 12-hour training on topics including safety, curriculum, and discipline and child development. The candidates will spend their first year co-leading a classroom and can work as a lead teacher in their second year.

The program also offers a network of support for the new teachers, which Nathan believes is an important step toward keeping them in the field. Educate ME matches the fellows with mentors and connects them with other men going through the program.

The recruitment process has been slowed down by the coronavirus. When Nathan and Mwaafrika started accepting applications in January, they went into schools and organizations to meet people face-to-face. The state’s stay-at-home order forced them to move recruitment online.

Now they’re about a quarter of the way toward their 50-person goal, Mwaafrika said, and are accepting applications on a rolling basis.

While the program offers an opportunity for people who have been laid off due to the economic recession, Nathan said, they “still want people that have it in their heart to want to make a difference and change lives.”

One of the new fellows, Damani Gibson, said he has always enjoyed working with children, and he’s excited about the impact he could have on young students’ lives.

“Sometimes it just takes that one person to say ‘Hey, you can do this, you can do that, I’m here with you, I’m here to walk these steps with you to get you to where you want to be,’” he said.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22331994/boyd_gerald.jpeg)