by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Oct 6, 2021 | Black History, Headline News |

(RNS) — Fannie Lou Hamer was an advocate for African Americans, women and poor people — and for many who were all three.

She lost her sharecropping job and her home when she registered to vote. She suffered physical and sexual assaults when she was taken to jail for her activism. And stories of her struggles reached the floor of the 1964 Democratic Convention — and the nation — when her emotional speech aired on television.

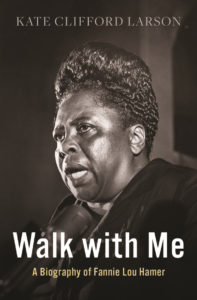

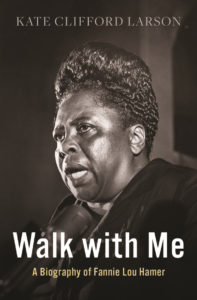

Historian Kate Clifford Larson has written a new book, “Walk With Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer,” that reveals details of the faith and life of Hamer, who was born 104 years ago Wednesday (Oct. 6) and died in 1977.

“Walk with Me: A Biography of Fannie Lou Hamer” by Kate Clifford Larson. Courtesy image

Inspired by young Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers who preached Bible passages about liberation at her church in Ruleville, Mississippi, in 1962, Hamer became a singer and speaker for equal rights and human rights.

“She crawled her way through extraordinarily difficult circumstances to bring her voice to the nation to be heard,” Larson told Religion News Service. “And she knew that she was representing so many people that were not heard.”

Larson spoke to RNS about Hamer’s faith, her favorite spirituals and how music helped the activist and advocate survive.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you decide to write a biography of Fannie Lou Hamer and how would you describe her as a woman of faith?

I published a book about (Harriet) Tubman and Hamer is so similar to Harriet Tubman, only 100 years later. I decided to start looking into her life and thinking I should do a biography of Hamer. I just became hooked. There were so many similarities, and things I could see in Hamer that I just thought, we need to have a refresher about Fannie Lou Hamer and the strength of her character and how she survived such incredible adversity and found the same kind of solace that Harriet Tubman did — in her faith, in her family and the community — to keep going and fighting and to try to make the world a better place.

It seems she is relatively unknown in many circles despite the credit she’s given by civil rights veterans for her work.

It is curious that she is not well known broadly. And I hope that changes, because I think we need to look back sometimes to see how far we’ve come. And with Hamer, the things that happened to her — she faced the world by confronting that trauma, and that violence, without hate. And the only way she could do that was through her faith, and talking to God and saying: Where are you, what is happening here, give me the strength to carry this weight and to move forward. And she did. She knew hate could really destroy her — that feeling of hating the people that were trying to kill her and subjugate her. She managed to rise above it because she had a greater mission in front of her.

Why did you title the book “Walk With Me”?

The title is from the song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She was brutally beaten, nearly killed, in the Winona, Mississippi, jail in June of 1963. As she lay in her jail cell, bleeding and bruised and coming in and out of consciousness, she struggled to hang on and her cellmate, Euvester Simpson, a teenage civil rights worker, was there with her. She asked Euvester to please sing with her because she needed to find strength and she needed God to be with her. So she sang that song “Walk With Me, Lord.” She needed to feel there was something bigger that would help her survive those moments where it wasn’t so clear she would survive. And I found it so powerful that she would do that. She survived that night and was able to get up and walk the next morning.

What other spirituals and gospel songs were particularly important to Hamer as she fought for voting rights and other social justice causes?

One of her favorites is “This Little Light of Mine.” She sang that everywhere, all the time. It’s kind of her anthem. There were some other spirituals, but really, most of the ones she sang a lot during the movement were those crossover folk songs, rooted in Christian spirituals, like “Go Tell It on the Mountain.” She grew up not only in a very strong church environment, the Baptist church, but she grew up in the fields of Mississippi where there were work songs in the fields, call and response songs. Where she grew up was actually the birthplace of the Delta blues music.

She also quoted the Bible to the people she differed with. Were there particular biblical lessons Hamer applied to her fight to help her fellow Black Mississippians?

She used the Bible in many different ways. She used it to shame her white oppressors who claimed also to be Christians, following the path of Christ. She would use the Bible and say: Are you following this path by what you’re doing to me, to my fellow community members and family members? And she used the Bible passages to remind Christian ministers: This is your job, and what are you doing up on that pulpit? You’re telling people to be patient. Well, in the Bible it says stand up and lead people out of Egypt.

You wrote about William Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, Hamer’s congregation, throughout the book. What happened there, over the years as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and other groups used it as a place for meetings, classes and rallies?

The church, the ministers participated in the movement and had meetings in that church at great risk to themselves and to the church, and in fact, the church was bombed a couple of times even though the fires were put out, fortunately, very quickly. There were residents in the community that took their lives and put them on the line. They were at great risk, to go to those meetings, to conduct those meetings, to go out and do voter registration drives. It was all centered on the church community because that was really the only community buildings in many of these places where people could meet together to have these discussions.

You said Hamer was at a crossroads as she first listened to those SNCC (pronounced “snick”) activists seeking more people to join their cause.

She experienced trauma, and she had been sterilized against her will — she didn’t give permission — and she had gone through this very deep depression, and it tested her faith. It tested her understanding of the world, and she came out of that and went to this meeting in Ruleville in 1962 and when she heard those young people and their passion and their willingness to put their lives on the line for her, she viewed them as the “New Kingdom.” So it was more than a crossroads for her. It was a moment where she could see the future in these young people, and she called them the “New Kingdom (right here) on earth.” If they were willing to stand up and risk their lives then she could, at 45, 46 years old, stand up herself. That was a crossroads. She made that choice to stand up, publicly, and move forward.

by Christine A. Scheller | Aug 17, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

Martin Luther King Jr. didn’t emerge on the civil rights scene fully formed but drew from a rich spiritual and intellectual heritage that he owed, in part, to his mentor, the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays. Mays served as president of Morehouse College in Atlanta for 27 years and delivered the eulogy at King’s funeral. In the first full-length biography of Mays, Dr. Randal M. Jelks, associate professor of American and African American studies at the University of Kansas, provides an in-depth look not only at Mays’ meteoric rise from humble Southern roots to international acclaim, but he also sheds new light on the fertile soil out of which the Civil Rights Movement grew. UrbanFaith talked to Jelks about the book earlier this week. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Martin Luther King Jr. didn’t emerge on the civil rights scene fully formed but drew from a rich spiritual and intellectual heritage that he owed, in part, to his mentor, the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays. Mays served as president of Morehouse College in Atlanta for 27 years and delivered the eulogy at King’s funeral. In the first full-length biography of Mays, Dr. Randal M. Jelks, associate professor of American and African American studies at the University of Kansas, provides an in-depth look not only at Mays’ meteoric rise from humble Southern roots to international acclaim, but he also sheds new light on the fertile soil out of which the Civil Rights Movement grew. UrbanFaith talked to Jelks about the book earlier this week. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

UrbanFaith: Why is Benjamin Mays important?

First, most people think of the Civil Rights Movement as being born in December 1955 with Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott. In point of fact, it had a long and winding road to becoming a fully understood national movement. You had to have teachers and people who laid out the groundwork for what began in ’55, and so I wanted remind readers, particularly those readers who are not familiar with institutions within the Black community, of the great intellectual leaders and teaching that went on to fully fuel a movement.

Mays grounded his civil rights philosophy in the Christian faith, but moved away from his conservative Baptist heritage into Social Gospel theology.

That’s correct. The Social Gospel emerged from a German Baptist, Walter Rauschenbusch, who was a minister in Hell’s Kitchen in New York. When you see people dying everyday from disease and impoverishment (these were European immigrants) at an alarming rate, you say, “How is this individualized gospel helping these people? Is it only teaching them to be saved for the moment and live through this hell on earth?” Mays concluded the same thing from both the impoverishment he faced in rural South and the kind of totalizing exclusion that he saw in Jim Crow America.

You write that Rauschenbusch didn’t say much about the sin of racism, but that Mays saw in Rauschenbusch’s theology something he could use. Did Mays express any resistance to adopting the Social Gospel in light of Rauschenbusch’s relative silence on race?

Mays is like all people in that you find a creative spark. You read somebody and their experience is different than yours, but you find something in that text that triggers your thinking. I think that’s how Mays used Rauschenbusch. If he was going to remain Christian, then the gospel has to speak to societal issues; it couldn’t just speak to individual issues. If it was just personalized and just a communitarian voluntary organization, it could not be a force for mobilizing social change. That’s what Mays would probably say.

You said Mays’ emphasis was more on Jesus’ humanity than on his divinity. Did Mays believe in the divinity of Christ?

If you use the old theological terms, people with high Christology hold to the divinity of Christ; with low Christology, they emphasize the humanity of Jesus. So Mays would have had a low Christology in the sense that what he sees as important about Jesus are the actions that he took and what he stood for. For Mays, Jesus’ death on the cross is because of his actions in facing the state. It is the ethics of Jesus and the teachings of Jesus that are far more long-lasting than whether Jesus arose from the dead. He doesn’t have this sort of Anselm theology of the Middle Ages that says Jesus is the sacrifice for all of us.

That sounds consistent with his belief that faith is action. Is there a direct link there?

Yes, I think he would be much more aligned with 1 and 2 John than with the Apostle Paul.

Why did Mays think it was so important to ground his arguments for racial equality in the Christian faith?

Mays could rightly assume that the American narrative began with religious freedom and the theology of those English Protestants of all stripes coming to the British colonies of North America. So, even if we had Catholics and Eastern Orthodox in the United States, that narrative sort of shapes American life and culture. And, in his era, people still went to church in great numbers. So it made sense sociologically for him to speak the language of the people and through these institutions that had moral influence.

Later when the Black Power movement arose, Mays seemed to be skeptical that civil rights could be achieved apart from a moral or spiritual foundation. Is that correct?

He wasn’t skeptical. I think the generation coming after him was much more skeptical about the ideas of moral suasion in light of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and other things. They begin to see that political power, and some would even argue revolutionary struggle by means of arms, was much more important. You can see everyone growing tired of state-sanctioned violence that was done against young civil rights activists. So there’s a real move to say that faith is power. Mays is now in his 70s as the Black Power movement emerges and he begins trying to figure out if it is right to speak in this language. What I was trying to show was that in that moment, everything was really kind of confused and here was a man who had spent his life trying to mobilize Christians to tackle the problem of race. Mays was trying to give them some grounding.

A huge part of his work involved educating Black pastors. Has that legacy been born out?

There is still the need to educate Black clergy. Mays wanted to educate them in a certain way. Black people are like everybody else in America; they have a diversity of opinions. I don’t think he was as explicit as he might have been that he wanted to educate Black pastors in a liberal, progressive way in order to empower a social movement. There are lots of pastors who go to conservative seminaries and who buy whole hog the arguments. I would think that would be short-sighted if they really looked at the conditions within Black communities.

He seemed to have some prejudice against the low-church experience.

RANDAL M. JELKS: The Civil Rights Movement “had a long and winding road to becoming a fully understood national movement.”

Mays, as a part of his generation, really didn’t look favorably on the experience of Pentecostals in particular and people in store-front churches. I think his own biases came out there. Also, he was biased because he was a Baptist. In his era, even though he was trying to be non-denominational, he doesn’t quite know what to do with people who are in ever-growing numbers becoming Pentecostal store-front preachers. He hadn’t thought that out. And, of course, you’re shaped by your education, and here he was a University of Chicago PhD. I don’t think his teachers at that time would have given much thought to the growing numbers of Pentecostals. Even some of his critics, when they were criticizing the negro’s church, saw that bias.

He had a strong commitment both to Christianity and democracy that you connect with his Baptist ecclesiology.

That’s right. It’s very much rooted in the long history. Alexis De Tocqueville wrote about this in Democracy in America. One of the things that we don’t give enough credit to is the Protestant dissenting tradition that is a shaping force in American democracy. The constitution of the United States very much resembles the way the Presbyterian church is ordered and the governing structures of the country very much resemble long-held patterns that govern the Calvinist tradition. Freedom of conscience is also very much an inheritance that he picked up on as a dissenting tradition.

I thought it was fascinating to read about how Mays’ trip to India to meet Ghandi and his debates with the Dutch Reformed South African theologian shaped his view of the American experience.

He didn’t see the problems of the United States as separate. This is the privilege of being able to travel at a time when most Americans would not have seen the world. He very much realized that the problems of Black liberation were the problems of liberation for people around the world in many different settings. He was particularly drawn to the affinity between Apartheid and Jim Crow. He had heard those same debates about whether the Bible condones a separate reality. He wanted to strike that down. In terms of Ghandi, what he saw was that black people in America were a racial minority, so to pick up 1917 Bolshevik-style revolution would have been tantamount to signing a death warrant. This is where his Christian ideals come in. Non-violent struggle keeps people’s dignity and personhood in tact. This is something very important for him, coming out of the Baptist tradition, which teaches that God is no respecter of persons, but every person is precious in God’s sight. That’s what struck him about Ghandi in his long struggle against the British.

His connection with Martin Luther King Jr. went back to when King was a high school early-admission student at Morehouse.

King’s father was a trustee of Morehouse and a graduate of Morehouse himself. And so, for young King to be entrusted to Benjamin Mays was a very good thing for his family. The Mays’ consistently had not only Martin King, but other young students over to dinner, and introduced them to national figures from A. Philip Randolph to Dorothy Height. They’re all at dinner listening to these conversations, soaking them up. What a wonderful education. So King becomes very much persuaded through Mays that ministry could have a social application, because, as he writes, he had planned to go to law school. He had not planned to pick up things like his father, who he thought was too conservative in his approach to ministry. So Mays becomes this new model of a highly educated Black minister and socially connected to world-wide issues.

You write that King modeled his early civil rights persona after Mays. In what way did he emulate Mays?

The reason I write that is we forget that Martin King was 26 years old when the Montgomery bus boycott starts. When I was 26, I was an adult, but I was still very much a young adult with no experience whatsoever. And so you take on personas as you are trying to find your voice, sort of like painters and musicians. They play like other musicians until they find their own creative spark and energy. King was already a really fine young orator, but in terms of being fully formed, I don’t think so. I think he was still trying to give homage to Mays as a kind of father figure. That’s why he was very much trying to be poised and deliberate like Mays. Biographies kind of annoy me because they are written as though this man has no developmental history like all of us. When King’s home is bombed in Montogmery, Mays has to persuade his father to back off, because his father wants him to pack up and move back to Atlanta. Mays becomes an intervening force.

And yet, Mrs. Mays complained at one point that King was borrowing from Mays without attribution.

Preaching is an art like music. If you hear a lick, and that’s good, you’re going to borrow that lick. But she certainly was not worrying about the greater cause. She was like, “That’s my husband’s work and he should be giving more credit where credit is due.”

In your estimation, what do we owe Benjamin Mays?

I don’t know that he would say we owe him anything, but for me, both as a religious person and an intellectual, I first wanted to show that there were a variety of models out there. It’s very important that we hear from different voices within the community. Of course there are conservative pastors who come on, like E.V. Hill in Los Angeles. Certainly E.V. Hill back in the day was very conservative. Mays also is a critic of people like Billy Graham and Reinhold Neibuhr.

Second, if Benjamin Mays had been president of Harvard, there would have been 1000 books written about him, because in a 27-year stretch, he graduated and was looked up to by people like Martin Luther King Jr., Marian Wright Edelman, Julian Bond, David Satcher, who was Surgeon General of the United States, and on and on and on. If he had been president of Harvard, people would say, “What kind of educator does that? What’s the shaping force for him to make this place so rich?” But it’s a little Black school for men, and he saved it from closing its doors. I think one of his great legacies is this connection between education and religious faith and thought.

Lastly, long before this term “public intellectual” was coined, he was indeed a public intellectual, writing primarily to Black people. I don’t think you would have seen too many White writers, like Neibuhr, saying in a column that the Korean War is wrong. There have been thousands of books written on Neibuhr, who said that the Cold War was a good thing. I was trying to say there are other voices out here who had significance and who have historical legacies that are important.

Martin Luther King Jr. didn’t emerge on the civil rights scene fully formed but drew from a rich spiritual and intellectual heritage that he owed, in part, to his mentor, the

Martin Luther King Jr. didn’t emerge on the civil rights scene fully formed but drew from a rich spiritual and intellectual heritage that he owed, in part, to his mentor, the