by Kathryn Post, RNS | Jul 28, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News |

(RNS) — The earliest known depiction of biblical heroines Jael and Deborah was discovered at an ancient synagogue in Israel, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced last week. A rendering of one figure driving a stake through the head of a military general was the initial clue that led the team to identify the figures, according to project director Jodi Magness.

“This is extremely rare,” Magness, an archaeologist and religion professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, told Religion News Service. “I don’t know of any other ancient depictions of these heroines.”

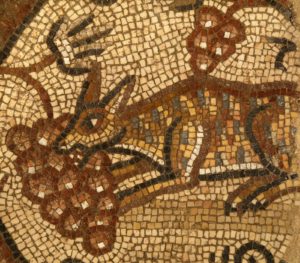

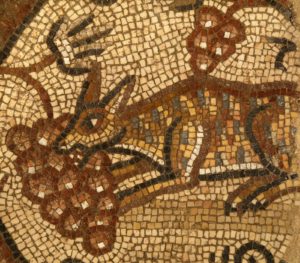

The nearly 1,600-year-old mosaics were uncovered by a team of students and specialists as part of The Huqoq Excavation Project, which resumed its 10th season of excavations this summer at a synagogue in the ancient Jewish village of Huqoq in Lower Galilee. Mosaics were first discovered at the site in 2012, and Magness said the synagogue, which dates to the late fourth or early fifth century, is “unusually large and richly decorated.” In addition to its extensive, relatively well-preserved mosaics, the site is adorned with wall paintings and carved architecture.

The fourth chapter of the Book of Judges tells the story of Deborah, a judge and prophet who conquered the Canaanite army alongside Israelite general Barak. After the victory, the passage says, the Canaanite commander Sisera fled to the tent of Jael, where she drove a tent peg into his temple and killed him.

The newly discovered mosaic panels depicting the heroines are made of local cut stone from Galilee and were found on the floor on the south end of the synagogue’s west aisle. The mosaic is divided into three sections, one with Deborah seated under a palm tree looking at Barak, a second with what appears to be Sisera seated and a third with Jael hammering a peg into a bleeding Sisera.

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic.

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic.

“The value of our discoveries, the value of archaeology, is that it helps fill in the gaps in our information about, in this case, Jews and Judaism in this particular period,” explained Magness. “It shows that there was a very rich and diverse range of views among Jews.”

Magness said rabbinic literature doesn’t include descriptions about figure decoration in synagogues — so the world would never know about these visual embellishments without archaeology.

“Judaism was dynamic through late antiquity. Never was Judaism monolithic,” said Magness. “There’s always been a wide range of Jewish practices, and I think that’s partly what we see.”

These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.

These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.

by Ben Finley, Associated Press | Oct 15, 2021 | Black History, Headline News, Heritage |

Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, holds a one-cent coin from 1817 on Wednesday Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. The coin helped archaeologists confirm that a recently unearthed brick-and-mortar foundation belonged to one of the oldest Black churches in the United States. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (AP) — The brick foundation of one of the nation’s oldest Black churches has been unearthed at Colonial Williamsburg, a living history museum in Virginia that continues to reckon with its past storytelling about the country’s origins and the role of Black Americans.

The First Baptist Church was formed in 1776 by free and enslaved Black people. They initially met secretly in fields and under trees in defiance of laws that prevented African Americans from congregating.

By 1818, the church had its first building in the former colonial capital. The 16-foot by 20-foot (5-meter by 6-meter) structure was destroyed by a tornado in 1834.

First Baptist’s second structure, built in 1856, stood there for a century. But an expanding Colonial Williamsburg bought the property in 1956 and turned it into a parking lot.

First Baptist Pastor Reginald F. Davis, whose church now stands elsewhere in Williamsburg, said the uncovering of the church’s first home is “a rediscovery of the humanity of a people.”

“This helps to erase the historical and social amnesia that has afflicted this country for so many years,” he said.

Colonial Williamsburg on Thursday announced that it had located the foundation after analyzing layers of soil and artifacts such as a one-cent coin.

For decades, Colonial Williamsburg had ignored the stories of colonial Black Americans. But in recent years, the museum has placed a growing emphasis on African-American history, while trying to attract more Black visitors.

Reginald F. Davis, from left, pastor of First Baptist Church in Williamsburg, Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist, and Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, stand at the brick-and-mortar foundation of one the oldest Black churches in the U.S. on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. Colonial Williamsburg announced Thursday Oct. 7, that the foundation had been unearthed by archeologists. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

The museum tells the story of Virginia’s 18th century capital and includes more than 400 restored or reconstructed buildings. More than half of the 2,000 people who lived in Williamsburg in the late 18th century were Black — and many were enslaved.

Sharing stories of residents of color is a relatively new phenomenon at Colonial Williamsburg. It wasn’t until 1979 when the museum began telling Black stories, and not until 2002 that it launched its American Indian Initiative.

First Baptist has been at the center of an initiative to reintroduce African Americans to the museum. For instance, Colonial Williamsburg’s historic conservation experts repaired the church’s long-silenced bell several years ago.

Congregants and museum archeologists are now plotting a way forward together on how best to excavate the site and to tell First Baptist’s story. The relationship is starkly different from the one in the mid-20th Century.

“Imagine being a child going to this church, and riding by and seeing a parking lot … where possibly people you knew and loved are buried,” said Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist. She is also board president of the Let Freedom Ring Foundation, which is aimed at preserving the church’s history.

Colonial Williamsburg had paid for the property where the church had sat until the mid-1950s, and covered the costs of First Baptist building a new church. But the museum failed to tell its story despite its rich colonial history.

“It’s a healing process … to see it being uncovered,” Harshaw said. “And the community has really come together around this. And I’m talking Black and white.”

The excavation began last year. So far, 25 graves have been located based on the discoloration of the soil in areas where a plot was dug, according to Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology.

Gary said some congregants have already expressed an interest in analyzing bones to get a better idea of the lives of the deceased and to discover familial connections. He said some graves appear to predate the building of the second church.

It’s unclear exactly when First Baptist’s first church was built. Some researchers have said it may already have been standing when it was offered to the congregation by Jesse Cole, a white man who owned the property at the time.

First Baptist is mentioned in tax records from 1818 for an adjacent property.

Gary said the original foundation was confirmed by analyzing layers of soil and artifacts found in them. They included an one-cent coin from 1817 and copper pins that held together clothing in the early 18th century.

Colonial Williamsburg and the congregation want to eventually reconstruct the church.

“We want to make sure that we’re telling the story in a way that’s appropriate and accurate — and that they approve of the way we’re telling that history,” Gary said.

Jody Lynn Allen, a history professor at the nearby College of William & Mary, said the excavation is part of a larger reckoning on race and slavery at historic sites across the world.

“It’s not that all of a sudden, magically, these primary sources are appearing,” Allen said. “They’ve been in the archives or in people’s basements or attics. But they weren’t seen as valuable.”

Allen, who is on the board of First Baptist’s Let Freedom Ring Foundation, said physical evidence like a church foundation can help people connect more strongly to the past.

“The fact that the church still exists — that it’s still thriving — that story needs to be told,” Allen said. “People need to understand that there was a great resilience in the African American community.”

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic.

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic. These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.

These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.