by J. Kameron Carter, RNS | Oct 7, 2019 | Commentary |

Botham Jean’s younger brother Brandt Jean hugs convicted murderer and former Dallas Police Officer Amber Guyger after delivering his impact statement to her after she was sentenced to 10 years in jail, on Oct. 2, 2019, in Dallas. Guyger shot and killed Botham Jean, an unarmed 26-year-old neighbor in his own apartment last year. She told police she thought his apartment was her own and that he was an intruder. (Tom Fox/The Dallas Morning News via AP, Pool)

RELATED: A TEST OF FAITH: KEY WITNESS IN GUYGER TRIAL DEAD

Last week, fired Dallas police officer Amber R. Guyger, who is white, received a sentence of 10 years in prison for the murder of an unarmed black man, Botham Shem Jean.

While the sentence of 10 years for Jean’s murder certainly didn’t sit well with many, the other events of the courtroom are what have become the subjects of discussion — the words of grace, forgiveness, love and well-wishes offered by Jean’s younger brother to Guyger, capped off by a warm embrace. And if that were not enough, Judge Tammy Kemp, also an African American, added grace upon grace by going to her office to retrieve a Bible. After handing it to Guyger, the judge, too, embraced Guyger tearfully and warmly.

This scene of grace, forgiveness and reconciliation operates almost like a ritual. We saw it in 2015 when relatives of the nine victims murdered by Dylann Roof in the shooting inside an AME church in Charleston, South Carolina, told Roof “I forgive you.” We saw it again when then-President Barack Obama eulogized Pastor Clementa Pinckney, one of those killed by Roof in that Charleston church, by singing “Amazing Grace How Sweet the Sound …”

The show of grace and forgiveness toward Guyger, like those before it, requires that we ask some hard questions. What if “grace” and “forgiveness” and their compulsory racialized performance are part of what makes this anti-black world keep on ticking? What if grace and forgiveness work in the interest of anti-blackness? And finally, what if grace and forgiveness are part of what must be refused in order to bring to an end an anti-black and brown world?

I know these are profane questions for a society that holds up forgiveness as hallowed virtues. But I raise them not to cast judgment on Jean’s younger brother. The Jean family is grieving. They are in a process of healing in the wake of violence and irreparable loss. My questioning of the virtue of forgiveness and grace in civil society does not begin with the individual.

Rather, I raise these questions to get at how America is structured through race.

President Barack Obama leads mourners in singing the song “Amazing Grace” as he delivers a eulogy in honor of the Rev. Clementa Pinckney during funeral services for Pinckney in Charleston, S.C., on June 26, 2015. Pinckney was one of nine victims of a mass shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Photo by Brian Snyder/Reuters

That is, in asking about the value of forgiveness and grace within the American social and political structure, I am asking about how the anti-blackness of American society works through religion-like rituals and liturgies of grace and forgiveness. I’m interested in how grace and forgiveness function publicly, how they script roles around blackness and death within a society organized around whiteness as the sign of proper life, or the life that is properly human. In this context, police violence and forgiveness rituals work to secure the common good and civil society. They work to secure America as a project of religion. Such religion may be thought of as “the religion of whiteness.”

Sociologist Robert Bellah coined the phrase “American civil religion” to explain how a secular nation maintains a religious dimension that suffuses public culture, from the political realm to civil society itself. That religious dimension has embedded within it beliefs, symbols, and ritual practices — the most well-known being the inauguration of U.S. presidents.

But Bellah’s concern was not just with the history of American religious belief, symbols and rituals. He came to his insight about the working of American civil religion in a moment when the American fabric was being torn by internal strife. It’s as if through his work as a sociologist Bellah was channeling the racial melancholy of a nation in fear and despair. The moment of crisis that he was trying to make sense of was the violence against black life and the protest movements of the 1960s.

Bellah’s idea was that the belief in and commitment to the sacred ideal of equal rights to all humans as the natural law guiding the American project is what America has always drawn on. He makes a case that the Founding Fathers in their exodus from the Old World to the new drew from the reservoir of this civil religion to found the nation. Later in America’s history, Abraham Lincoln, as a kind of savior, drew from the civil religion reservoir as well, though in his case, it was to preserve a nation in the internecine distress of the Civil War.

Notwithstanding Bellah’s great insight about the operations of American civil religion, what he nonetheless failed to grapple with was the degree to which America as a religious project rooted in the higher ideal or the natural law of human equality and freedom for all rested on an inequality within the ranks of the human ideal of freedom.

Bellah failed to address how America, as a project guided by the ideal of human freedom and equality, was predicated on settler colonial genocide and the ongoing use of black lives as property to rework stolen land and to build the national treasury. Within this structure of violence and death, blackness cannot matter for itself but only for its usefulness. In short, Bellah did not account for anti-blackness, which is not America’s original sin but its DNA.

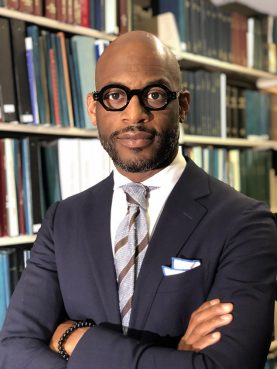

J. Kameron Carter. Courtesy photo

It is within this framework that the sacredness, sanctity and compulsory rituals of forgiveness must be understood. American religion needs black (and native) forgiveness in order to keep the national fantasy of civil society, which is anti-black, alive. After racial crisis and distress, American religion turns to rituals of forgiveness and grace carried out by those structurally positioned as black to re-cohere itself around its ideals of being the beacon of human equality and freedom. In fact, the rituals of forgiveness can be thought of as structural performances of the ideal made visible for an instant. These rituals of courtroom forgiveness display the “rightness” and sacredness of America as a project, confessed, as it were, by those who suffer under that project.

Again, what I am dealing with here is the American racial structure, not individuals. I’m dealing with why, within the religion of whiteness, whiteness needs black forgiveness to maintain itself. Black forgiveness is part of the ritual work of absolving or extending salvation to America. It is part of the work of re-cohering or saving whiteness in a moment of crisis. Should such black forgiveness be withheld, whiteness or the American religious project would face a potential collapse. It might suffer a “white out,” a possible end of the world or an end of its world.

But could the end of the world, a white out, be an alternative understanding of forgiveness, perhaps even an alternative religious orientation? Can there be a forgiveness that does not absolve guilt but brings the anti-black world to an end? Could there be a poetics of forgiveness that pressures forgiveness as we know it? Could there be a forgiveness that ends forgiveness, a forgiveness at the end of the world? Let’s hope so.

(J. Kameron Carter is a professor of religious studies at Indiana University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)

by Bobby Ross Jr., RNS | Jun 1, 2019 | Social Justice |

The nightmare never goes away.

Almost nine months have passed since Amber Guyger, an off-duty Dallas police officer still in uniform, entered Botham Shem Jean’s fourth-floor apartment and opened fire, killing the beloved song leader and Bible class teacher as he prepared to watch a football game on TV.

Still, the grief and the heartache never stray far from Bertrum and Allison Jean, parents of the 26-year-old accountant who left his native St. Lucia — a small island in the Caribbean — to attend Harding University in Searcy, Ark., and later worked for PricewaterhouseCoopers in Dallas.

Botham Shem Jean sings at the Dallas West Church of Christ in September 2017. Photo by Namon Pope

The desire to see their son, to touch his smiling face, to hear his beautiful voice sing praises to Jesus once again grips the Jeans all the more during trips to this Texas city, where Botham Jean’s life ended suddenly on a Thursday night in September.

“For me, every day it’s going to be on my mind, especially as we are here in Dallas,” said Bertrum Jean, who traveled with his wife to attend the recent Dallas Racial Unity Leadership Summit, hosted by the Dallas West Church of Christ — Botham Jean’s home congregation — and sponsored by the Carl Spain Center on Race Studies and Spiritual Action at Abilene Christian University in Texas.

“It’s as if it just happened,” the father said of his son’s death. “That’s how I feel.”

For Allison Jean, occasions such as the racial unity summit — dedicated in Botham Jean’s memory — and a simultaneous mission trip by Harding students to St. Lucia make her proud of the difference her son made in his short life.

“I see his work in all of this,” said the mother, wearing a #BeLikeBo T-shirt during an interview at the Dallas West church.

“It’s like a roller coaster,” she added. “There are days when I feel that God has taken him for a reason, and I get comfort that he’s with the Lord. Then there are days when I miss his physical presence, and I miss his telephone conversations.”

Months after Botham Jean’s death, trauma strikes his parents in unexpected ways.

While in Dallas, they needed to obtain medical records for an insurer. At Baylor Medical Center, where their son was taken after the shooting, they learned he initially was identified as a John Doe.

“That hurts because Botham was not a John Doe,” Allison Jean said. “He did so much, and he was so affable and always so upbeat in everything. He didn’t deserve to die.

“I know there’s a time to live and a time to die,” she added, referring to Ecclesiastes 3, “but certainly not in the way he did. I feel a wicked act was inflicted upon him right in his own home. That, for me, is the most hurtful part of it.”

Mugshots of Amber Guyger in 2018. Public records photo

WFAA-TV in Dallas recently obtained and broadcast a recording of Guyger’s 911 call from Botham Jean’s apartment.

Guyger has said she mistakenly parked on the fourth floor instead of the third floor, where she lived directly below Botham Jean’s residence. She said she confused his place with her own and thought he was a burglar.

On the 911 tape, Guyger repeatedly insists that “I thought it was my apartment” and voices concern that “I’m going to lose my job.”

Three days after the shooting, police charged Guyger with manslaughter. Later, she was fired and indicted by a grand jury on an upgraded murder charge. Her trial is set for September, a year after Botham Jean’s death.

“That was very, very, very hard,” Allison Jean said of the 911 recording.

“Listening to it, it sparked some anger within me because I’m not hearing the dispatcher pay much attention to him,” the mother added. “I didn’t hear the dispatcher ask about his condition, whether he was breathing, whether he was responsive. … And I’m wondering whether it was because it was a police-involved shooting that the victim didn’t matter.”

Allison Jean, a former top government official in St. Lucia, said she believes the tape was leaked in an effort to gain sympathy for Guyger.

At the Dallas Racial Unity Leadership Summit, an attendee wears a “Justice for Bo!” shirt. Photo courtesy of ACU’s Carl Spain Center

“I think it’s wrong,” she said.

For many, “Justice for Bo!” has become a rallying cry seen on T-shirts and social media hashtags.

“In addition to grieving his loss, I’m consumed with ensuring he gets justice,” Allison Jean said. “I read all the news articles that bear his name. I’m in touch with the attorneys from the DA’s office to find out about progress from the case.”

The family filed a civil lawsuit in federal court, arguing that the city and Dallas police “failed to implement and enforce such policies, practices and procedure for the DPD that respected (Botham) Jean’s constitutional rights.”

But lately, especially after a right-wing radio host characterized her as a scheming mom looking to get rich off her son’s death, the fight has made her weary, Allison Jean said.

In a Twitter post, family attorney Lee Merritt condemned the shock jock’s statement as “dangerous, defamatory and uniquely evil.”

“Right now, since I came to Dallas, I’ve just been thinking about whether I should really fight for justice,” Allison Jean said. “I know the one just God is the one whom I serve. So I keep thinking, ‘Should I just leave everything up to him?’”

Asked what justice would look like, she replied, “I thought justice would mean some punishment to the person who inflicted harm (on Botham Jean). But right now, since I realize we’re dealing with principalities and powers — we’re dealing with a secular world and not only the spiritual that we believe in — I’ll just leave it up to the Father.”

For his part, Bertrum Jean said he knows “nothing could bring Botham back to me.” No outcome in a criminal or civil court will change the fact that his son died.

Allison and Bertrum Jean, parents of Botham Jean, reflect on the Christian Acappella Music Awards paying tribute to their slain son after his death. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr.

“All my mind is on is, I want to see him again,” the father said, his voice choked with emotion. “I know he’s in a place where he should be, with the Lord. I want to be in heaven with him.

“Honestly, she’s the last person on my mind,” the father said of Guyger. “I don’t mind seeing her, and I have no hatred for her. Everybody who knows me, I’m about love.”

Whatever happens in the justice system, Bertrum Jean said, he’ll leave it in the Lord’s hands.

“Honestly, they could give her 100 years in prison, and I would take no pleasure,” he said. “Until I could see my Botham again, I will not be happy.”

Focus on positive change

The four-day racial unity summit brought the family — Bertrum Jean, Allison Jean, older sister Allisa Charles-Findley and younger brother Brandt Jean — to Dallas.

Bertrum and Allison Jean address the Dallas Racial Unity Leadership Summit at the Dallas West Church of Christ. Photo courtesy of ACU’s Carl Spain Center

They sat close to the front as Jerry Taylor, founding director of ACU’s Carl Spain Center, welcomed conference attendees. About 350 Christians from across the nation registered for the summit.

“Our presence here … speaks to our commitment to keeping the beautiful life and the horrific death of our beloved Botham Shem Jean alive,” Taylor said. “We will not suffer memory loss when it comes to recognizing the great tragedy of what the Jean family lost, what Dallas West lost, what the city of Dallas lost and what the world lost when Botham innocently lost his life.”

Dallas West minister and elder Sammie Berry, described by Botham Jean’s parents as his “Texas father,” told the crowd the slain Christian “was an outstanding young man with a bright future.”

“While he lived, he let his light shine on all of those who came near him,” Berry said. “So we’re here to honor him, but we’re also here to bring about some positive change.”

Allison Jean said of the summit: “Anything that will promote what Botham stood for, I fully support it. Racial unity is one of the things that Botham really tried to do. In fact, I don’t think he even recognized race because he was always with everyone. He blended very well at Harding, which is predominantly white.”

A mission team from Harding with the Jean family and other St. Lucia church members during a trip several years ago. Photo courtesy of Todd and Debbie Gentry

At the same time as the Dallas event, a dozen-person mission team from Harding landed in St. Lucia.

That island nation of 180,000 people is where Botham Jean dreamed of winning souls to Jesus and running for prime minister one day.

Harding teams led by Todd and Debbie Gentry, college and outreach ministers for the College Church of Christ in Searcy, began annual trips to St. Lucia in 2013.

At the time, Botham Jean worked as a student intern for the campus ministry. The Gros-Islet Church of Christ, where Bertrum Jean serves as a part-time preacher, was a new church plant on the island’s north end.

“We spent hours discussing the possibilities of how a team of Harding students could help grow and encourage those followers,” said Debbie Gentry, who with her husband became Botham Jean’s “Arkansas parents.”

The shirt worn by Harding mission team members on a recent trip to St. Lucia. Photo courtesy of Todd and Debbie Gentry

On the latest trip, students spent four days in a Gros-Islet elementary school, teaching health and wellness, social studies and religion. That school is the same one where the original mission team coordinated a day camp that Botham Jean helped arrange.

“Our relationship not only with this school but with the ministry of education in St. Lucia has been cultivated,” Debbie Gentry said. “We have been invited to teach in all the schools in the island.

“It is amazing how free we were to talk about God and our faith,” she added. “We sang religious songs freely and prayed in all the classrooms. In all subjects, we were encouraged to speak about our faith in Jesus Christ.”

Nonetheless, the trip was difficult for all who knew Botham Jean, she said: “This year, we are walking with the entire church through grief and healing. Our hearts are broken over the tragic death of our dear friend and brother. Without a doubt, we have felt Botham’s absence in a big way.”

But just as Botham Jean “served because he loved God with all his heart, soul and mind,” she said, the Harding team did the same — knowing that he would be pleased.

The family has established the Botham Jean Foundation, with his sister serving as president, to keep his memory alive and serve vulnerable communities in the U.S. and St. Lucia.

Allison Jean, right, mother of shooting victim Botham Shem Jean, hugs a mourner after a prayer vigil Sept. 8, 2018, at the Dallas West Church of Christ. RNS photo by Bobby Ross Jr.

On Sept. 6 — the anniversary of his death — the foundation plans a “Be Like Bo” Day that will feature the launch of a mentorship program.

“It’s a hard day, but we want to change it and bring good out of it,” said Charles-Findley, a member of the Kings Church of Christ in Brooklyn, N.Y.

After the racial unity summit, Bertrum and Allison Jean flew home to St. Lucia to join the Harding group.

Even before returning to the island, though, they braced themselves for the torment that they’d experience there.

St. Lucia, like Dallas, stirs so many memories, so much anguish.

“I miss him being there, just going to the various homes that he visited,” Bertrum Jean said of past St. Lucia mission efforts. “It breaks my heart that he won’t be there for that work.”

The nightmare never goes away.

(Bobby Ross Jr. writes for The Christian Chronicle, where this story first appeared. The original version of this story can be found here.)