by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Sep 6, 2018 | Headline News |

The months ahead of midterm elections, often a time of lower turnout among African-Americans and others, have become a focus of passionate activity by black Christian leaders.

“The attacks on the Voting Rights Act and other setbacks in civil rights have alerted the faith community that we need to take action,” said the Rev. Barbara Williams-Skinner, co-chair of the National African American Clergy Network. “We need to be proactive and not reactive.”

It’s been five years since the Supreme Court invalidated a key provision of the VRA, and voters in almost two dozen states face stricter rules. In response, black denominations and networks focused on people of color and the poor are gearing up in hopes of getting more people to the ballot box in November:

- This week, leaders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church plan to continue their “AME Righteous Vote” initiative with mobilization briefings, Capitol Hill meetings and a “Call to Conscience” vigil at Lafayette Square across from the White House.

- Faith in Action, the grassroots organization formerly known as PICO National Network, hopes to reach more than a million people in 150 cities with phone calls and door-to door visits before Election Day on Nov. 6.

- A “Lawyers and Collars” program co-led by the Skinner Leadership Institute and Sojourners plans to train clergy on voter protection, hold meetings with state elections officials and spend Election Day at the polls with lawyers to assist voters.

Stricter rules at polling places — such as ID laws — could lead to people being turned away on Nov. 6. Pastors and other leaders can serve as advocates on their behalf, said Williams-Skinner, who is also CEO of the Maryland-based institute.

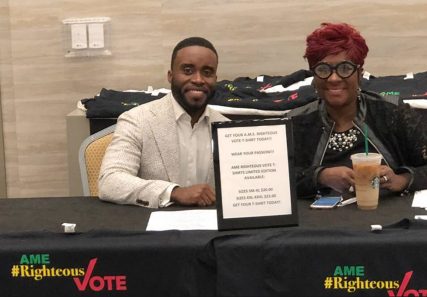

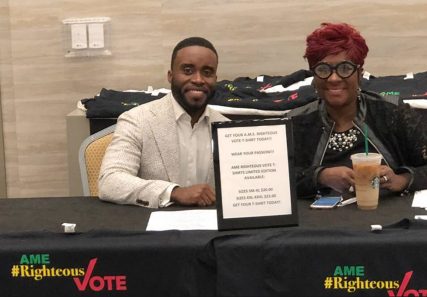

Willie Barnes II and Marlaa MeShon Hall Reid participate in an AME #RighteousVote Empowerment Seminar in Atlanta on June 25, 2018. Photo courtesy Bishop Frank M. Reid III

“We’re saying that vulnerable voters need to have protection and we believe that the most respected leaders (and) the influential stakeholders should be there,” she said. “As they stand in line with people, people will stay in line no matter what happens.”

Before its Washington-area activities this week, the AME Church held an “annual empowerment seminar” in June in Atlanta to encourage its leaders to be involved in educating prospective voters in the upcoming elections. In one announcement, Bishop Frank M. Reid III, chair of the denomination’s Social Action Commission, stressed the need for turnout “in this important spiritual and political season.”

In an interview, Reid explained that the call to elective action relates directly to the desire of church members to address social justice issues.

“We’re concerned about voter registration and voter turnout because without those things we cannot make America fair for the elderly who need affordable health care, our children, especially poor children,” he said, “who in the past received health care and food.”

Likewise, Faith in Action is talking with prospective voters about issues they care about, from the alleviation of poverty to mass incarceration. As the midterms near, the network is partnering with historically black denominations and justice-centered evangelical organizations to focus on minority communities that generally get little attention in get-out-the vote efforts.

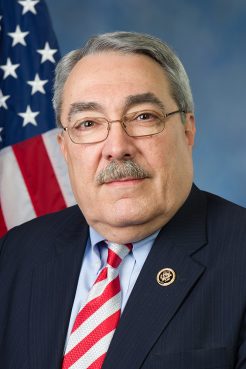

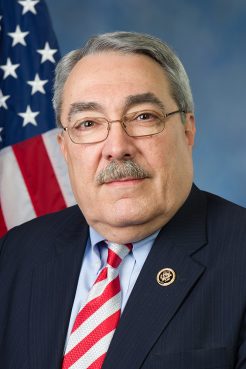

Rep. G.K. Butterfield. Photo courtesy Creative Commons

“Our work is really about making sure that our communities have access to resources, to skills, to tools that can maximize the vote,” said the Rev. Michael McBride, director of Faith in Action’s Live Free campaign.

Although pre-election activity is reaching a new volume with the election just two months away, some groups shone attention on the issue earlier in the year.

At the annual convention of the Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network in April, U.S. Rep. G.K. Butterfield, D-N.C., was among the speakers on a panel about the black church and voter mobilization. He explained that congregants can’t knock on doors as representatives of their congregation and advocate for a particular candidate. But they can be involved in a range of nonpartisan activities.

“If the church is engaged in a get-out-the vote effort, you can use a church van, church bus, church resources as long as it’s not a partisan activity,” said Butterfield, a lifelong Baptist who co-moderated the panel featuring clergy and political action committee leaders.

Church of God in Christ Bishop Talbert Swan, who was one of the NAN panelists, said in a recent interview that the changes in voting rules that often affect African-American communities — such as reductions in early voting opportunities — have made the initiatives more necessary.

“I think there’s a renewed sense of urgency because it seems that the nation is trying to go back to a time prior to voting rights of African-Americans,” said Swan, who cited the Supreme Court’s nullification of a key provision of the VRA. “While it’s still on the books, we essentially right now don’t have a Voting Rights Act, which is the reason why states across the nation can opt to put in place voter suppression regulations and laws.”

Bishop Talbert Swan, the leader of the Church of God in Christ’s Nova Scotia jurisdiction, addressed a summit of the Seymour Institute for Black Church and Policy Studies at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 21, 2018. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

RELATED: 50 years after Voting Rights Act, black churches fighting voting restrictions

The Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas said that in the past, the Supreme Court was seen as an ally, handing down dramatic civil rights court decisions, such as the Brown v. Board of Education ruling that declared school segregation unconstitutional.

Now, she said, with the Supreme Court turning more conservative, congressional races are crucial.

“Particularly when we talk about civil rights and people of color and African-Americans, our progress has come because we’ve had the court on our side,” said Douglas, dean of the Episcopal Divinity School and canon theologian of Washington National Cathedral. “We don’t have that. We’ve lost that.”

Trump’s 2016 win, which shocked and disappointed many black faith leaders, has certainly been a galvanizing factor as some voters head to the polls with renewed energy.

Black Protestants made up 7 percent of voters in the 2016 election, according to Pew Research. Ninety-six percent voted for former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, while only 3 percent voted for Donald Trump.

The Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, dean of New York’s Episcopal Divinity School and canon theologian of the Washington National Cathedral, at the Poor People’s Campaign rally in Washington on June 23, 2018. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Overall, African-Americans made up 10 percent of voters, according to Pew. Ninety-one percent supported Clinton, while 6 percent supported Trump. Pew also reported their turnout was down compared with the 2012 election.

But, citing how the black faith community was credited with helping defeat Roy Moore in his bid to become an Alabama senator, Douglas said it is possible to have successful get-out-the vote campaigns that remain nonpartisan.

“You don’t have to tell people who to vote for,” she said. “You don’t have to be partisan. You just have to tell them to vote and you trust your constituency.”

by Jelani Greenidge, Urban Faith Contributing Writer | Apr 8, 2013 | Headline News, Jelani Greenidge |

In 1963, Malcolm X famously referred to the assassination of President Kennedy as America’s chickens coming home to roost – a bold statement to a nation still mourning the loss of its president. When pressed to elaborate in an interview, he explained his comments by saying that Kennedy’s murder was the culmination of a long line of similarly violent acts perpetrated by the U.S. government.

Today, the political pundits continue to focus on the U.S. Supreme Court, which is expected to render a series of judgments with direct relevance to the legal institution of marriage. And most of the political left is united under the banner of what they refer to as “marriage equality,” the idea that same-sex couples should be allowed to marry and enjoy the same legal benefits conferred on heterosexual marriages.

And while most speculation is focused on either what should or will happen, I’m more concerned with what has already happened, specifically in the intersections of church life and civic duty. The Black church, though generally conservative socially and pro-traditional-marriage, has been unknowingly complicit in the hijacking of civil rights rhetoric by progressive liberal activists advocating for same sex marriage. Black clergy need to own up to the fact that the demand for civil rights from gays and lesbians is another case of chickens coming home to roost.

Diversity in religious Black thought

Rev. Irene Monroe, author, public theologian, and syndicated religion columnist, is a prominent supporter of same-sex marriage. (Photo Credit: IreneMonroe.com)

Now, I realize that referring to “Black clergy” and “the Black church” may give some the impression that Blacks are monolithic and uniform, always on the same page. This has never been true. At the dawn of the 20th century, the two most prominent Black leaders were Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, whose approaches differed greatly in tone and substance. In the 1960’s, Dr. King and Malcolm X were polar opposites. Even now, there are worlds of difference between the Christianity of President Obama and that of Ben Carson or Herman Cain. There are a variety of political and ideological flavors in the expression of Black organized religion and its connection to politics.

So it’s logical for certain, more left-leaning factions within the black church to promote open-and-affirming policies with officially sanctioned LGBT ministries. For these folks, civil rights for the LGBT community is the next logical step in their evolution of faith-based activism.

However, most African-Americans who believe in the gospel of Jesus Christ also believe that homosexuality is a sin. We may have a measure of empathy for gays and lesbians because of the ways in which they’ve been ostracized and persecuted over the years, but we still resent the comparison between gays and blacks as people with morally equivalent struggles. Instead, we resonate with articles like Voddie Baucham’s “Gay Is Not the New

Rev. Voddie Baucham, author of Gay is Not The New Black and pastor of preaching at Grace Family Baptist Church in Spring, Texas. (Photo Credit: Gospelcoalition.org)

Black,” primarily because, except for a few of the most light-skinned among us, Black folks have never had the privilege of choosing whether to come out of the closet.

This latent resentment probably burns the hottest from those believers in the Black community who have labored the longest, who are entrenched most directly in the ongoing battle, and who confront racialized economic disparities through the pursuit of better enforcement of civil rights. Their offense over the mostly-White gay activists borrowing the language and legacy of the Black civil rights struggle was crystallized by Dr. King’s youngest Bernice King in a 2005 march, when she said that her father “did not take a bullet for same-sex marriage.”

Unfortunately, these are the folks who helped same sex marriage become a foregone conclusion. Why? It’s all the focus on rights. In the Black church, we’ve elevated the pursuit of rights into an art form. We march, sing, and preach for our rights. “I got a right to praise Him,” said Karen Clark-Sheard. He’s a “Right Now God,” said Dorinda Clark Cole. “Receive it RIGHT NOW,” said Andrae Crouch.

Discipleship breeds activism, not vice versa

In our attempts to necessarily address local injustices, we’ve inadvertently modeled church life as consisting primarily of activism for social change, rather than as a place for spiritual discipleship. Not to say that we shouldn’t do both; outward social change should be a natural flow of spiritual discipleship. But the issue is of primacy – which do we do first, best, most naturally, and more completely? If we’re about a social cause more than we’re about being disciples, we might do all of the same programs, but for different reasons and in different ways.

Bishop Harry Jackson, pastor of Hope Christian Church and the founder of the High Impact Leadership Coalition, is a prominent supporter of marriage being defined as a one man, one woman covenantal relationship. (Photo Credit: TheHopeConnection.org)

So take mass incarceration, for example. It’s one thing if, in the process of learning how to consistently receive God’s grace and love, we recognize our value as being made in God’s image, then transfer that recognition to others (in this case, Black men) who are being disproportionately victimized by drug laws, police harassment and unfair sentencing biases that feed them into the prison industrial complex.

It’s another thing, though, if you show up at church and everyone’s always talking about this problem with Black men in prison and it’s really bad and c’mon people we’ve gotta DO SOMETHING about it because somehow Jesus doesn’t like it (maybe he was Black? not sure).

I’m exaggerating to make a point, but there’s so much Biblical illiteracy nowadays because as ministers we assume that people understand that it’s our faith that provides the emotional, moral and philosophical foundation for our civic engagement. But in a post-Christian society, that assumption is dangerous. After all, the Pharisees were very skilled at doing the right things for the wrong reasons.

Liberated theology

Liberation theology has been wonderful in helping people to contextualize contemporary suffering into the narrative of Biblical suffering, but we need other theological constructs and frameworks to fully engage people with the gospel in a multicultural context. Without balance, our liberation theology ends up becoming what I call “liberated theology” – where we tend to view the gospel only through the lens of the freedom to self-actualize.

And this is a problem, because it blurs the boundaries between our rights as citizens and our rights as believers. As a citizen, I support the idea that gay and lesbian couples should be able to enjoy all of the municipal benefits of marriage as sanctioned by the local state. But that’s different from my belief that as a believer in Christ, I really don’t have any rights, other than to be grateful for God pouring His love on us instead of His wrath.

Thus, my sexuality, like any other facet of my life, is subject to His wisdom and guidance, which is tied to my understanding of His Word. There are a lot of things I could do with my body that I choose not to, and some of them I avoid because I’m constrained by the laws of the land. But others of them I choose to avoid because God’s grace and mercy causes me to trust His principles, even when I don’t personally enjoy them, even when rationalizing my way around those principles is perfectly within my legal rights as a citizen.

If liberated theology is my only guidepost, I’m tempted to have a distorted view of the Scripture, where Exodus 9:1 is reduced to “let my people go,” rather than the full text of the verse, “let my people go, so that they may worship me.” The first part is connected to citizen rights, but the latter half is all about being humble worshipers in God’s kingdom.

So I don’t have a problem with people demonstrating with marriage equality. But I have a feeling that there would be less appropriation of civil rights language if our Black churches weren’t as focused on securing rights for the African-American community. And I know that part of our calling as Christians is to battle the injustice that we encounter. But I hope we can do it with the humility and freedom that comes from knowing we are fully loved and forgiven.

Mostly, I’d just rather our preachers would spend a little less time engaging 1 Cor. 6:9-10 (which denounces sin) and more time engaging 1 Cor. 8:9 (NIV), which says the following (emphasis mine): “Be careful, however, that the exercise of your rights does not become a stumbling block to the weak.”

by Natasha S. Robinson | Feb 7, 2013 | Entertainment, Feature, Headline News |

Mary J. Blige and Angela Bassett star as “Betty & Coretta” in Lifetime’s original movie (Photo credit: Richard McLaren/Lifetime.com)

The old saying goes, “Behind every great man, there is a woman.” I have observed, however, that “beside every great man, there is a woman.” Such is the case with Civil Rights advocates, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. While many are familiar with their stories, few know the stories of their devoted wives Coretta Scott King and Dr. Betty Shabazz. More surprisingly the friendship that formed between these two women after the assassinations of their husbands is an untold story.

That is until Lifetime boldly presented this bond of sister and womanhood in the television world premiere of “Betty and Coretta” last weekend. A corporate executive at A&E Network did confirm that the Shabazz and King families were not consulted for the film, noting the temptation for family members to protect their legacies. Given the documented inward fighting between siblings in both families, viewers can understand (at least partially) the network’s decision. Some of the heirs are not happy with the flick.

Ilyasah Shabazz, third daughter of Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz and author of Growing Up X, called the film “inaccurate.” There are a few grievances raised: Contrary to Ilyasah’s statement, there are several pictures available online portraying Dr. Shabazz’s head covered with a scarf. Whether or not Dr. Shabazz spoke on her death bed is somewhat irrelevant. The point is Mrs. King did come to be at her friend, Betty’s side in the days leading up to her death. According to the children, moreover, there was a house visit portrayed in the movie which never really took place. Whenever a person’s life is brought to a film there is a certain level of embellishment that goes with the territory because producers are attempting to share a big story in a finite amount of time; smooth transitions are needed to move the story line forward and still capture the big picture. With the aforementioned reasons in mind, one can hardly call Lifetime’s portrayal a work of fiction.

Lifetime took great care adding credibility to the film by featuring actress, Ruby Dee, as narrator of the movie and dear friend of the Shabazz family. The movie picks up right before the assassinations of Malcolm (February 21, 1965) and Martin (April 4, 1968), and opened with Ruby Dee (who recently turned 90 years old) setting the stage for the times of racism, war, and poverty in America. Throughout the film she continues sharing facts about the deaths of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, the Black National Political Convention (of 10,000 attendees where Coretta and Betty first met), the lobbying and six million signatures Mrs. King gathered to make Martin Luther King, Jr. a National Holiday, and she narrates all the way to the deaths of both phenomenal women.

The movie is not about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (Malik Yoba), Malcolm X (Lindsay Owen Pierre), or their legacies per se. The movie is also not about the King and Shabazz children. The movie focuses on two women who were powerful, strong, faithful, and devoted leaders in their own rights. The film spans three decades and weaves the lives of these two civil rights activists and shares how they stood for justice.

The Women

A pregnant, Betty Shabazz (Mary J. Blige) and her four daughters watched her husband being gunned down as he took the stage to deliver what became his last message. After Malcolm X’s assassination, Betty delivered twin girls, which made her a single mother with six small children. With the help of friends and those in her community, Betty cared for her family and earned a doctorate degree in high-education administration from the University of Massachusetts. She became an associate professor of health sciences at New York’s Medgar Evers College. She spent the rest of her life working as an university administrator and fundraiser, before she died on June 23, 1997 as a result of injuries sustained by a fire her 10-year-old grandson, Malcolm set in her home.

As a widow, Coretta Scott King (Angela Bassett) raised four children while remaining a leading participant in the Civil Rights Movement. She went from being her husband’s motivator and partner in the movement to being a justice advocate to the world. In addition to lobbying for the national King Holiday (first celebrated in January 1986), she became president, chair, and Chief Executive Officer of The King Center in Atlanta, GA. At the end of the movie, Ruby Dee notes that Mrs. King died in 2006, nine years after Dr. Shabazz, from ovarian cancer.

The movie goes beyond their advocacy works and humanizes these valiant women. It is difficult to know for sure the intimate conversations that took place between the two. There is one living legend, however, who is knowledgeable of at least some of those conversations, and that woman is Myrlie Evers-Williams, wife and widow of the first NAACP field officer, Medgar Evers. As widows of the Civil Rights Movement, Myrlie Evers-Williams shared a special bond with King and Shabazz. In the book, Betty Shabazz: A Sisterfriends Tribute in Words and Pictures, she wrote about a healing spa retreat the three of them took together. During the retreat, they committed not to talk about the assassinations of their husbands or the movement; they simply bonded as sisters and friends. She also wrote that “the three stayed in contact and tried to get together whenever they could.”

Lifetime briefly mentioned the retreat at the end of the movie (hence the purpose of the Betty Shabazz hospital bed scene). However, Myrlie Evers-Williams’ character only makes a brief appearance in the film when Dr. Shabazz took the position to teach at Medgar Evers College. Maybe one day, Myrlie Evers-Williams will tell her side of this story.

What Their Stories Mean for Us

All things considered, I believe we have a reason to rejoice with the production of this film. Mrs. King and Dr. Shabazz came together to shepherd the legacies of their husbands, but that is only part of their stories. The bigger story is these women stood together and turned their tragedies into triumphs. Even more important, both women used their faith, family, and friendships to advocate justice on behalf of women, children, the poor, and oppressed. They stood together and changed the world.

A twitter reflection by @lativida sums it up well: Take note all you dumb reality shows! This is how REAL BLACK WIVES act! These women knew real pain and persevered! #BettyandCoretta.

Betty and Coretta were strong in their own rights. They were single mothers who became grandmothers and they took care of their families. They took the mantles that were passed to them and used them as a foundation to build their communities and our nation. They remind us, each of us (the single mother, wife, or young person of any gender), of what we can do with faith, friendship, and forgiveness, for this, yes this is how real black wives behave! Thank God for their tenacity, legacies, and friendship.

by Amanda Edwards | Aug 15, 2012 | Entertainment, Feature, Headline News |

HARRY BELFAFONTE: “They have turned their back on social responsibility,” opined the activist and actor about today’s black celebrities. (Photo: David Shankbone/Wikipedia)

Harry Belafonte is a legendary entertainer, known for his iconic performances in films like Carmen Jones, Buck and the Preacher, and Calypso. And who can forget his award-winning “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)”? However, in a long and distinguished career, Belafonte’s greatest accomplishments arguably may be his involvement with the civil rights movement.

During the ’50s and ’60s, Belafonte was one of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s biggest supporters and endorsers. He fully believed in the message and movement that King worked so tirelessly to establish. Belafonte provided financial support for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as well as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Council (SNCC), and he also participated in several rallies and protests alongside King. Still a civic-minded crusader today at age 85, he continues to live his life as an outspoken activist for social justice and equality.

Belafonte has never been one to shy away from social commentary or hold his tongue in conversation. He has been known for his honest comments and straightforward critiques about politics, show business, and society.

In an interview last week with the Hollywood Reporter, when asked whether or not he was happy with the images of minorities portrayed in Hollywood, he caused a stir by calling out two famous black celebrities by name. “I think one of the great abuses of this modern time is that we should have had such high-profile artists, powerful celebrities,” Belafonte began. “But they have turned their back on social responsibility. That goes for Jay-Z and Beyoncé, for example.”

JAY-Z AND BEYONCE: Is it fair to compare the altruism and social involvement of today’s stars to those of the civil rights era? (Photo: Ivan Nikolov/WENN/Newscom)

Belafonte believes that industry heavyweights like Jay-Z and Beyoncé have a social responsibility to be outspoken regarding issues of race, prejudice, and civil injustices, mainly because they have the social influence and public platform to do so. Janelle Harris at Essence echoed those sentiments. “There’s been an ugly dumbing down when it comes to acknowledging and addressing pertinent issues, even having empathy for and interest in what’s impacting our community. It’s an attitude of detachment,” she said.

She added: “I agree with Harry Belafonte. I think young people could be doing more. Twenty, thirty, forty-somethings. It’s not just the celebrities, though they’re certainly part of the vanguard for making philanthropy and activism cool, which is unfortunately necessary for some folks to get involved.”

Jay-Z and Beyoncé are definitely the closest thing the black community has to pop-culture royalty today. The hip-hop power couple topped Forbes list this year as the world’s highest-paid celebrity duo, raking in a staggering $78 million. But are they giving back?

Guardian columnist Tricia Rose wonders as much. She writes, “It is undeniable that today’s top black artists and celebrities have the greatest leverage, power, visibility and global influence of any period. It is also true that few speak openly, regularly and publicly on behalf of social justice. Most remain remarkably quiet about the conditions that the majority of black people face.”

Many celebrities often take on a non-controversial role or use their celebrity indirectly as a fundraising tool, rather than taking an overt stance to engage civically. Rose continues to say that her previous statement is not intended to, “discount their philanthropic efforts,” but to raise awareness. And Belafonte’s lament illuminates a fundamental shift in black popular culture.

“As black artists have gone mainstream, their traditional role has shifted. No longer the presumed cultural voice of the black collective social justice, it is now heavily embedded in mass cultural products controlled by the biggest conglomerates in the world,” says Rose.

FREEDOM FIGHTERS: Belafonte (center) with fellow actors Sidney Poitier (left) and Charlton Heston at the historic civil rights March on Washington, D.C., in 1963.

Rose notes that individuals like Belafonte willfully sacrificed their safety and lives by marching with civil rights protesters under threat of police violence. His commitment and contributions are rare among modern superstars.

She adds: “In the history of black culture popular music and art has played an extraordinary role in keeping the spirit alive under duress, challenging discrimination and writing the soundtrack to freedom movements.” Visionaries like Paul Robeson, Lorraine Hansberry, and Nina Simone are a few that Rose believes understood that responsibility and made a conscious effort to better society through both their art and fame.

As for Beyoncé, the singer’s representatives did respond to Belafonte’s charge by citing a litany of the singer’s charitable acts, including funding of inner-city outreaches in her hometown of Houston, as well as donations to hurricane relief efforts in the Gulf Coast and humanitarian campaigns following the Haiti earthquake.

In fairness to Beyoncé and Jay-Z, it is not for any of us to judge how they use their money, nor to pressure them into being more generous than they already are. What’s more, the issues in today’s society are quite different than they were during the civil rights era. So, it might be unfair to impose those kinds of expectations on today’s African American celebrities.

Still, it’s hard not to feel that we do need more influential people with Belafonte’s mindset to help us reenergize the black community. His contributions over the course of his career have changed the world for the better and have proven that entertainers can be important difference makers for change and justice.