by Maina Mwaura, Urban Faith Contributing Writer | Sep 12, 2022 | Headline News |

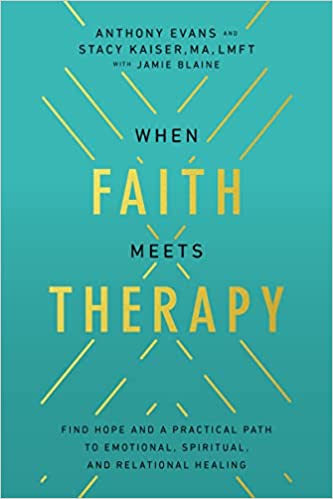

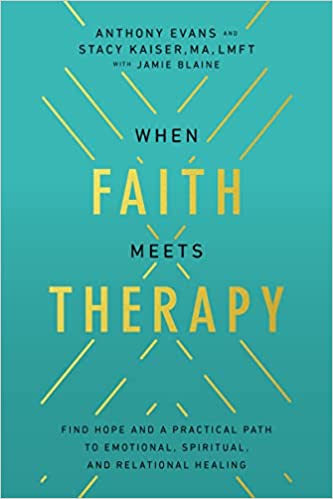

Singer, author, and worship leader Anthony Evans collaborated with licensed psychotherapist and TV personality Stacy Kaiser on a new book, “When Faith Meets Therapy: Find Hope and a Practical Path to Emotional, Spiritual, and Relational Healing.”

Evans, a well-known Christian musician and the son of renowned Pastor Drs. Tony and Lois Evans, and Kaiser, a sought-after professional, media personality, and speaker, met five years ago when he sought emotional, relational, and spiritual healing.

Evans, a well-known Christian musician and the son of renowned Pastor Drs. Tony and Lois Evans, and Kaiser, a sought-after professional, media personality, and speaker, met five years ago when he sought emotional, relational, and spiritual healing.

“I hit up Stacy after seeing credits role after a TV show. I saw her, and the way she handled a scenario. I’m desperate. Let me see these credits. And normally, I’m sure her staff was like, uh oh, crazy person alert, but they just looked me up and realized this dude’s not nuts. He just happened to find you on TV. And so are you willing to see him? And so she told her people, yes,” said Evans.

Kaiser led Evans through a process of internal renovation and continues as his personal therapist. The two opened the world up about their partnership through their When Faith Meets Therapy Zoom talks. With the release of their book, the duo takes the conversation around mental health and faith to the next level, packaging insights from Anthony’s personal experience with therapy and poignant takeaways from Kaiser.

“A therapist, client relationship is confidential except for things like if somebody is harming themselves or someone else or child abuse and things like that — so we had to have that conversation, but Anthony was on board, and we made a deal that he’s going to share his story. I’m not. And that’s what the book is. Anthony really talking about his story and giving his wisdom and then me giving therapeutic advice throughout — the kinds of things I would say to Anthony or any other client that I was working with,” said Kaiser.

The authors offer hope and practical steps to getting started on a mental health journey, examples of strategies that worked for Anthony and encourage readers to take the next step toward individualized professional help if needed.

“In our book, Stacy and I want to have an open, honest conversation about faith and mental health in a way that doesn’t make a person feel worse about themselves and their relationship with God,” writes Anthony. “A lot of faith meeting therapy is talking about boundaries and balance, power and responsibility, fear and healthy relationships. Mental, physical, and spiritual health are connected. It all works together.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Aug 29, 2022 | Headline News |

The Christian Methodist Episcopal Church has elected its second woman bishop and received its first episcopal address from a woman during its quadrennial General Conference.

“I think when you elect the first you have to be really careful that they just don’t become a token and so I was really excited,” said Bishop Teresa Jefferson-Snorton, who was the first woman elected in 2010 and serves as the secretary on the College of Bishops.

The Rev. Denise Anders-Modest, pastor of Trinity CME Church in Memphis, Tenn., and coordinator of the CME Commission on Women in Ministry, will serve the 2nd Episcopal District, which includes Kentucky, Ohio and Central Indiana.

The Rev. Denise Anders-Modest. Photo courtesy of Farish Street Baptist Church

Her forerunner was particularly pleased that voting delegates chose Anders-Modest as the second to win election to the role of bishop, not waiting until the last opportunity to add another woman to the CME episcopacy. “That’s also quite commendable that people were able to see her qualifications and not just, ‘oh, we need a woman bishop.’”

Jefferson-Snorton achieved another first this year, becoming the first woman to give the episcopal address — the message given on behalf of the bishops to the denomination — on June 25, the first official day of the gathering at the Duke Energy Center in Cincinnati. The meeting, which was attended by about 2,500 people, is set to conclude Friday (July 1).

She also was elected as the denomination’s new ecumenical and development officer, a role that no longer requires her to also lead a district of churches. Part of her role will be to seek resources to create and work on ministry and outreach programs at both the denominational and local levels.

“I see lots of our churches that are in communities that have such need but the local church itself doesn’t really have the capacity to go out and look for funds or even manage the program,” she said.

The delegates, who attended in person, also elected the second African bishop in the history of the denomination, which was founded in 1870 and claims 1.2 million U.S. members. It has sister churches and missions in 14 African countries, Haiti and Jamaica.

The Rev. Kwame L. Adjei, a member of the CME Church’s Judicial Council and a former associate pastor and high school chaplain in his native Ghana, will serve the 11th District, which is in East Africa.

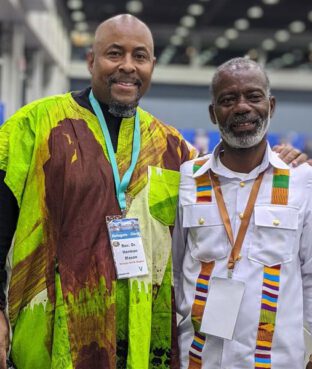

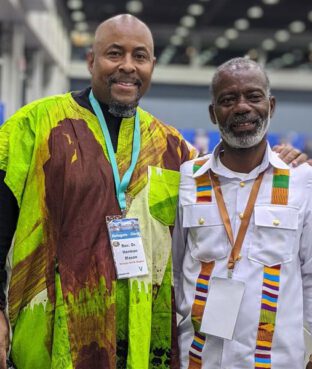

The Rev. Kwame Lawson Adjei, right, is the new bishop-elect for the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church’s 11th District, located in East Africa. Courtesy of CME Church Facebook

He will be the second African bishop. Bishop Godwin T. Umoette, the first African-born bishop was elected in 2010 and died earlier this year.

“Because we do consider ourselves the international church,” Jefferson-Snorton said, “bishops in the leadership needed to also include a voice that was not just the American voice but someone at the table of the College of Bishops who brought another cultural perspective.”

Other new bishops are: the Rev. Clarence K. Heath, pastor, Carter Metropolitan CME Church of Fort Worth, Texas, who will lead the 5th Episcopal District, based in Birmingham, Alabama; the Rev. Charley Hames Jr., senior pastor of the Beebe Memorial Cathedral in Oakland, California, who will lead the 9th Episcopal District, based in Los Angeles; and the Rev. Ricky D. Helton, senior pastor of Israel Metropolitan CME Church in Washington, D.C., who will lead the 10th Episcopal District, based in West Africa.

Despite temperature checks and other measures to keep the gathering free of COVID-19, some attendees tested positive during the General Conference.

Jefferson-Snorton, who also is board chair of the National Council of Churches, said she did not know how many people tested positive but she quarantined for three days after she learned her husband tested positive.

“No one has had to go the hospital,” she said. “It wasn’t like gaping holes in the delegation.”

In recent weeks, other gatherings of religious denominations, including the Southern Baptist Convention and the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), have had COVID-19 cases as well.

“We had a handful of attendees who reported they had tested positive for COVID-19 in the days following their trip to Anaheim,” said Jonathan Howe, vice president for communications of the SBC Executive Committee. “None of those with whom we spoke were able to identify the source of their specific case, nor did any report significant illness that required hospitalization.”

Preliminary meetings of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) featured reports of 13 cases of COVID-19, its stated clerk said in a June 23 statement posted on Twitter.

“We believe that this week’s small outbreak of positive cases did not originate from the Presbyterian Center or during General Assembly meeting times,” said the Rev. J. Herbert Nelson II about the gathering in Louisville, Kentucky. “Rather, the source of this outbreak appears to have occurred outside of official General Assembly activities involving receptions and other hospitality events.”

by Maina Mwaura, Urban Faith Contributing Writer | Aug 9, 2022 | Entertainment, Headline News |

From music educator to best selling author Brendan Slocumb has an unexpected journey. But his action packed novel The Violin Conspiracy is a fictional story based on his true life journey. UrbanFaith sat down with Brendan to talk about his book, his faith story, and what stories he wants to tell next. The interview is above. Information on the book is below.

—-

Most classical musicians are white, wealthy, privileged. Not Ray: he’s Black and comes from a single-family household, with a self-centered mother who actively blocks Ray’s aspirations. Only his Grandma Nora seems to care about his love for music. She gives him her old family treasure – a beat-up fiddle that hasn’t been played in eighty years. Ray confronts rampant discrimination from an establishment that believes that Black people cannot emotionally understand the music of dead white Europeans: Blacks should stick to hip hop, Gershwin, and jazz. A college music scholarship, and a professor’s mentorship, nurture Ray’s extraordinary talent and unstoppable ambition.

Then Ray discovers that Grandma Nora’s ancient violin is actually a rare and unique instrument that can take his playing to an entirely new level. The resulting media frenzy catapulted him into a solo violinist’s career. His star rises, but with success comes heartbreak: two lawsuits threaten to rip the violin away from him. In the first, his family claims that the instrument is rightfully theirs; in the second, the slaveholder family of his ancestors declare that Ray’s great-grandfather stole the violin from them. The two claims intertwine. Desperate to keep the violin, Ray makes a bargain that will have far-reaching and devastating consequences.

And then someone – his family? The slaveholder family? The mafia? – steals the violin. Ray has a month to raise five million dollars to pay the ransom before the Tchaikovsky Competition – classical music’s version of the Olympics – begins, and before the violin disappears forever.

In Moscow, under the glaring lights of musical stardom, Ray will not only compete, but will also discover what happened to the violin that means everything to him.

Evans, a well-known Christian musician and the son of renowned Pastor Drs. Tony and Lois Evans, and Kaiser, a sought-after professional, media personality, and speaker, met five years ago when he sought emotional, relational, and spiritual healing.

Evans, a well-known Christian musician and the son of renowned Pastor Drs. Tony and Lois Evans, and Kaiser, a sought-after professional, media personality, and speaker, met five years ago when he sought emotional, relational, and spiritual healing.