A Man on a Mission

Dwayne A. Jones with children from the Have Faith Mission Orphanage.

It started with a mission trip to Ghana, West Africa, in 2003, working with Habitat Global Village.

Before Dwayne A. Jones even landed in the country with the nonprofit group, he immediately started seeking out churches, not realizing how big Ghana is. The first church that came up was Amazing Grace Gospel International church. He found a name on the site to contact — Isaac Akorli. When Dwayne arrived in Ghana with the Habitat group, Isaac was waiting for him at the airport, having traveled 8 hours by bus to meet him.

“When he got there, he didn’t have anywhere to stay, so I invited him to stay in the room with my roommate and me from the Habitat group. We talked and chit-chatted. He wanted me to come to visit. I said, ‘No, I can’t separate from my team. This is my first time in the country, and I’m with a group of people.’ So I promised him that I would make another trip and come back,” said Jones.

And he did. It was the beginning of a friendship and shared ministry that would last nearly 20 years. Jones fell in love with the kids, people, and culture in Ghana.

Jones returned the following year and visited Isaac in the Volta Region, west of Togo. Isaac had active ministries there in about eight churches, seven in Ghana and one in Togo. Jones, an ordained Baptist minister at New Olivet Baptist Church in Memphis, TN, preached, baptized people in the ocean, and held a revival for eight days.

“I think it was 26 different locations. It was a great experience and some challenges too. When I was baptizing in the ocean there, they had to tie a rope around me to keep me from being pulled out by the waves,” said Jones.

He returned to Ghana several times with his teams. In addition to his ministry, Jones wanted to help the people. He initially focused on building houses as he did with Habitat. The people were always gracious, but as time went on and he traveled to remote villages and had one-on-one meetings with village chiefs, he started to ask people what they wanted, and housing wasn’t a priority.

“They said, ‘We don’t have a problem with housing. We need something for health care. We need something to educate our children. We’re okay living in little mud huts and little houses,” said Jones.

Have Faith Orphanage children in class learning to speak Portuguese.

With that, Jones, now 54, started to shift the focus of his trips. He partnered up with Americares, a global nonprofit organization focused on health and development that responds to individuals affected by poverty, disaster, or crisis, and arranged for doctors and different health care professionals to provide medical care in churches. On one of his trips, he brought a pediatrician from his church who took care of many kids with childhood obesity, diabetes, blood pressure, colds, and rashes. The medical professionals gave HIV/AIDS tests and educated women about personal hygiene items, birth control, diabetes, and blood pressure.

Have Faith Orphanage teens listening to Jones preach.

Often, well-intentioned foreign volunteers will come with their agenda for helping people in other countries. Jones was able to have a significant impact by simply asking people what they needed. That’s how the idea for creating a school to teach sewing came to fruition. He set up a meeting with the West Africa AIDS Foundation (WAAF), had an informal conversation, and took notes. There he learned about The Almond Tree, an income-generating project created for people living with HIV and AIDS in Accra, Ghana, by WAAF in partnership with the AIDS Committee of London in Canada. In The Almond Tree’s program, people make clothes, hats, and all kinds of items to sell. However, outside of Accra, poor people who wanted to do the same thing didn’t have electricity in the remote areas.

“I went to an internet café where they have old computers connected up to car batteries. I did some research, and I found out we could buy a sewing machine for $50. So I went and bought 15-16 sewing machines. We went to the remote village and took them there. Put them up on a table, and they screened women and brought women in, and they set up training to teach women how to sew and how to become self-sufficient by selling the clothes,” said Jones.

That training facility was named the Amazing Grace Sewing School.

Over the years, Jones’ missionary travels have expanded beyond Ghana and into India and Haiti. He has brought anywhere from two to eight people on various trips, including family, friends, educators, preachers, people who want to do construction, and church members. The only requirement is that they understand it’s a faith-based Christian trip, and they’ll need to participate and accept ministry opportunities, no matter where they are in their faith. It’s not a vacation. That said, it does take a lot out of him.

“Every time I go on a mission trip, I come back more tired than when I left. For one, it’s spiritually draining, and two, the travel … being a team leader, there’s a lot of logistics between food, immunizations, safety, internet access, currency exchange, lodging, coordinating with the host, and just making sure people have a great experience. It’s always stressful for me, but I’ve been doing it long enough it gets easier with time. There’s a lot involved before I go,” said Jones.

Danger and Corruption

Being a missionary can have dangerous consequences. In 2005, Jones was in Togo when Gnassingbe Eyadéma, the president of Togo at the time, died of a heart attack. Eyadéma’s son was attempting to take over the government, and a war broke out. He was trapped in Togo and couldn’t get out. They had shut the country down, and the border was closed.

“In Togo, the country’s national language is French, but they have that native African tongue. I didn’t speak French or the native tongue. There was a guy who was an interpreter, and we’re at the internet café. We see these guys in big pickup trucks with bandanas and suits on, and I said, ‘Oh, we got a soccer gang.’ You know I didn’t know what was going on,” said Jones. “I had to call the embassy, and they were sending some Apache helicopters, but the pastor was able to negotiate with the people at the border, and they got me out of the country.”

And then there are the nefarious activities of corrupt people. In 2020, even with the COVID pandemic raging, he traveled to the Have Faith Mission Orphanage in Haiti. No one came in or left except the teachers. Even he only left twice during his stay. At the orphanage, they follow the US protocols with mask-wearing. However, Jones said around town that wasn’t the case. He pointed out that at the time, very few people were diagnosed with COVID. In the two days he was there, they had zero cases. That said, he was asked multiple times in the airport to see his negative COVID test.

“It was four checks to see if you had your COVID test and a temperature check on your forehead before you could even get to baggage claim,” said Jones.

Like his visits to Africa, he tried to bring the Haitian kids vitamins, medicine, support items for personal hygiene, education supplies, and even some toys and fun things. In Haiti, the orphans haven’t necessarily lost their parents. In many cases, the parents aren’t able to care for their children, but they still maintain a relationship. It’s like foster care, adoption, and an orphanage all in one. However, he didn’t make it out of the airport without people stealing some of his supplies and goodies.

“I had 12 bags of candy for the kids. They stole candy at customs,” said Jones. “I had 14 little fire tablets for them to do wifi and go online. The airport police wanted to take those, but they extorted $100 instead. The guy was there from the orphanage and everything.”

Jones says he’s had customs agents demand money for his medicines, and they’ve confiscated syringes and items to treat diabetes. But in one particular case, the corruption resulted in souls being saved. Jones had to return to the airport a few times to get all of his luggage. One time on his way back to the airport, he saw a little girl walking down the street. The people he was with dismissed her as a peasant girl, but he wanted to talk to her. With a translator, he learned her name was Nadez and that she was from a remote village and hungry. He got her some food and made her one of those twisty balloons entertainers often give young kids.

“I ended up asking her, ‘Do you know Jesus?’ She said no. So I told her a story about Jesus Christ and asked her if she’d like to accept Jesus. She said yes. So I prayed with her right there. She accepted Jesus, and before I left, there were 200 and some people there who accepted Jesus at the airport,” said Jones. “I’d go with one intention, and then something else happened. I’d tell people maybe there was a reason my medicine was confiscated from me so that I could meet Nadez.”

I Build By Faith

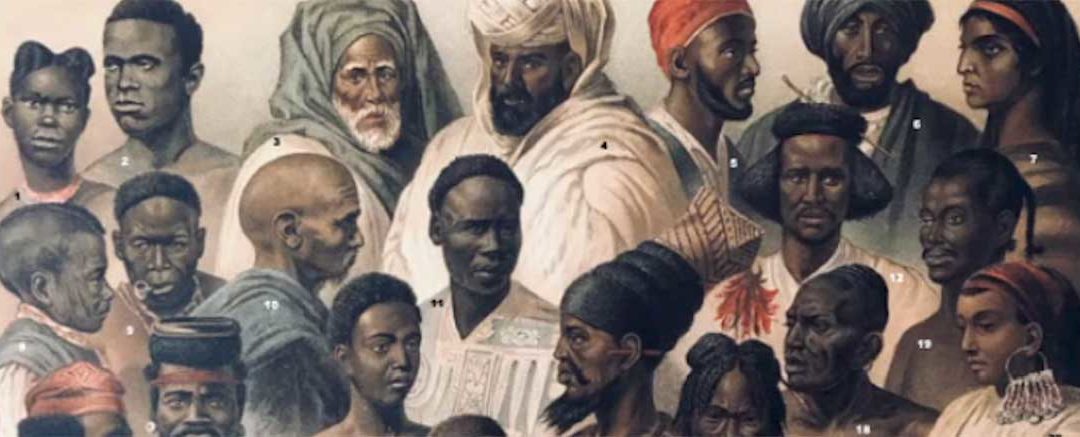

Jones and children from Have Faith Orphanage.

Jones is an international missionary, but he also has a construction business. He received a degree in architectural engineering from Tennessee State University and a master’s in management from the University of Phoenix, where he’s currently working toward a Ph.D. in organizational management. Dwayne A. Jones Construction Company, LLC, is what has helped to fund his missionary trips. As much as he’s accomplished around the world, he’s also created a name for himself by taking on poverty in the United States through building personal “tiny houses” for the homeless, organizing bike drives, and sprouting up community gardens. But poverty in the United States still isn’t like it is in Haiti or Africa.

“It’s totally different because even with our people in poverty, they have way more means and access. It’s on a scale that will blow your mind because if a person is in poverty here in the United States, they have access to running water somewhere, even if you take a homeless person. They can go to a restaurant, and they can go to use the bathroom facility. In Haiti, you don’t have running water anywhere,” said Jones.

He puts all of his community service efforts and ministries under the umbrella organization of “I Build By Faith.” It started out as connecting his faith to his construction business and profession, but now it’s all about community building and changing lives. Jones says the most significant difference between Haiti and Africa is the distance when it comes to poverty.

“The same construction, people, same food, same problems, same poverty, they’re just in a different place. It is so similar, it’s eerie,” said Jones. “I would like to provide a facility where young people here in my community, Orange Mound (Memphis, TN), can help rebuild this community and be an international hub to bring children from Haiti and Africa to Orange Mound and take kids from Orange Mound to those countries and get that exposure. I want to make a global educational facility for both sets of children, here and abroad. This is pre-pandemic, but I still believe by faith that it can happen.”