by Matthew J. Cressler and Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jan 2, 2020 | Faith & Work |

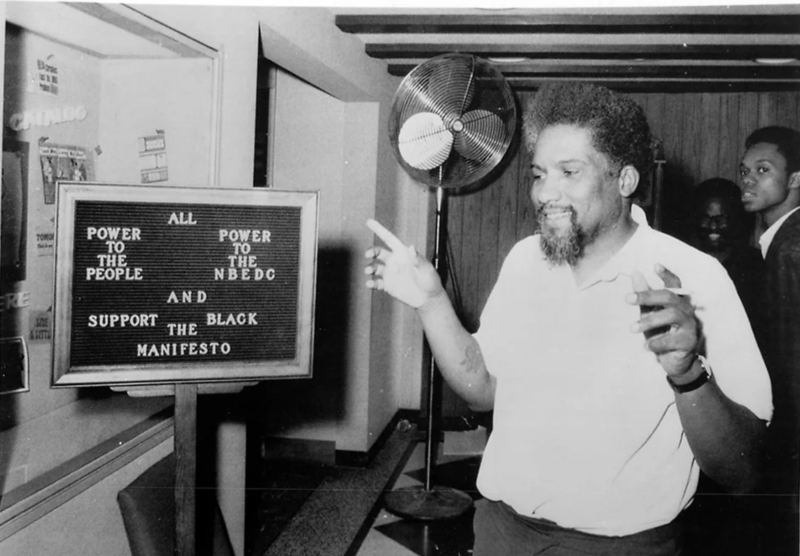

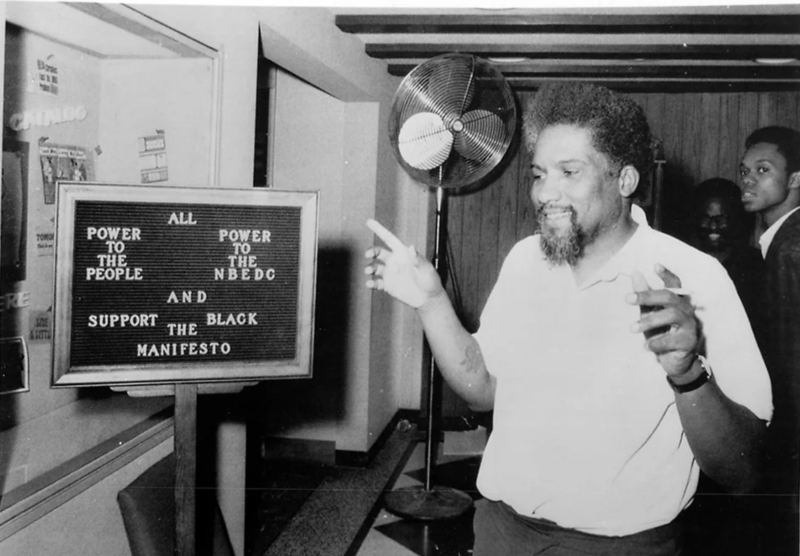

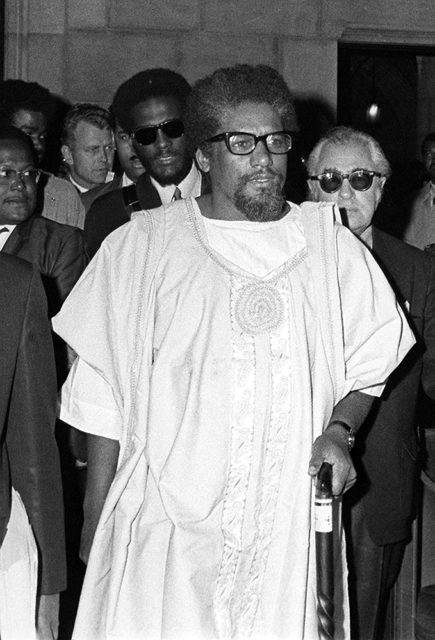

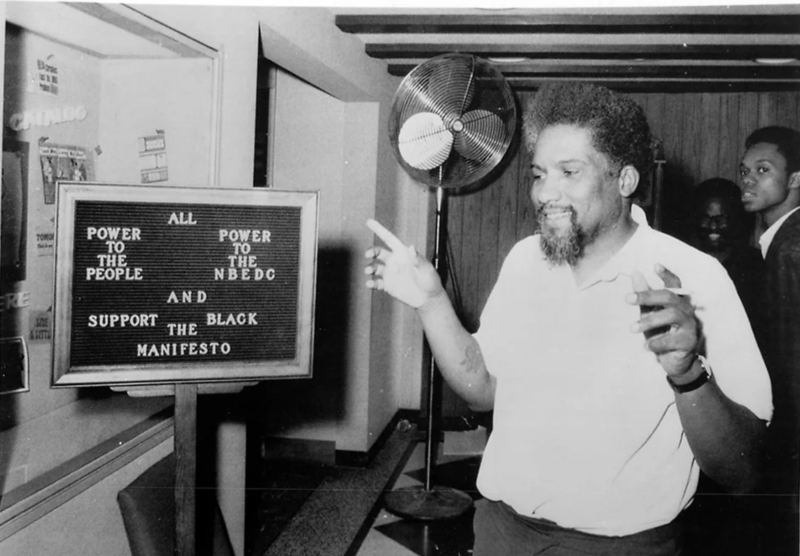

James Forman, chief spokesman for the Black Manifesto, inspects a bulletin board in New York’s Interchurch Center after he and supporting members of the National Black Economic Development Conference seized three floors of offices in 1969. The NBEDC sought $500 million in reparations from the white religious community. RNS file photo

On a Sunday morning in May of 1969, as clergy processed into the sanctuary of New York’s august Riverside Church, civil rights activist James Forman vaulted into the pulpit to demand $500 million in reparations for the mistreatment of African Americans from white churches and synagogues.

At the time, Forman’s interruption represented the high point for the reparations movement. A week before, Forman had debuted a radical proposal for racial justice known as “the Black Manifesto” for 500 black activists gathered in Detroit for the National Black Economic Development Conference.

“(W)e know that the churches and synagogues have a tremendous wealth,” the manifesto stated, “and its membership, white America, has profited and still exploits black people.”

The conference determined, by a 187-63 vote, that it was time for white Christians and Jews to pay reparations and demonstrate a willingness to fight “the white supremacy and racism which has forced us as black people to make these demands.”

Riverside, then a mostly white liberal Protestant congregation whose neo-Gothic landmark building was financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr., would be deeply divided over the next few years over Forman’s challenge. As the activist brought his manifesto to other congregations and denominations, Riverside established a lecture series and a “Fund for Social Justice” that aimed to raise $450,000 over three years to help the poor in the local community. It fell short of the goal by almost $100,000.

Members of the congregation file out after Sunday morning worship services at Riverside Church in New York on July 20, 2014. The building is modeled after the 13th-century cathedral in Chartres, France. (AP Photo/Kathy Willens)

The Black Manifesto’s demands never caught fire in the broader U.S. religious community. The Rev. Gayraud Wilmore, a black Presbyterian leader in New York City in 1969, recalled 50 years later how religious institutions responded.

“I saw them withering and unable to step forward and say ‘Let’s be the church,’” said Wilmore, now 98. “I saw no bold action taken on our side to go along with the bold action Forman was taking.”

Five decades later, the reparations debate has re-entered the national spotlight, with some religious institutions leading the way.

Earlier in December, Reform Jews, declaring that “racial inequity is present in virtually every aspect of American life,” voted overwhelmingly to support a U.S. commission to develop proposals for reparations and urged conversations in their congregations to redress systemic racism.

In recent months, Virginia Theological Seminary, Princeton Theological Seminary and Georgetown University have all announced plans to fund initiatives that would benefit the descendants of slaves, while Episcopal dioceses in New York and Long Island made million- and half-million-dollar commitments as reparations committees continued their work.

In May, the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland voted to study reparations and urge congregations to “examine how their endowed wealth is tied to the institution of slavery.”

Maryland Episcopal Bishop Eugene Sutton testifies before the U.S. Congress about reparaions in June 2019. Video screengrab via C-SPAN

Maryland’s African American bishop, Eugene Taylor Sutton, said tears came to his eyes when the measure passed at the diocese’s general convention with no dissenting votes, and he realized that the assembled delegates, representing a membership that is 90% white, “got it.”

“They get this thing called justice, and when you put it in a frame that there is a basic injustice in this nation of stealing from generations of people and that has a direct effect on today, then people,” Sutton said, “they say, ‘OK, we got to get that fixed.’”

Sutton, who testified before Congress in June with writer Ta-Nehisi Coates to advocate for the idea of a U.S. reparations commission, emphasized that reparations can come in many forms. Starting next month, members of his diocese will begin to consider options such as providing better access for people of color to home buying, job training and faculty positions at seminaries.

It has taken some American religious institutions 50 years to get their heads around reparations. When Forman hijacked that Sunday morning service, two-thirds of Riverside worshippers, including the minister, stormed out in protest. After activists occupied offices in the Interchurch Center of New York, a court-issued restraining orders to bar Forman from the building. In Missouri, manifesto supporters in St. Louis carried out a series of “Black Sunday” protests, interrupting local services, which led to confrontations with white church members and arrests.

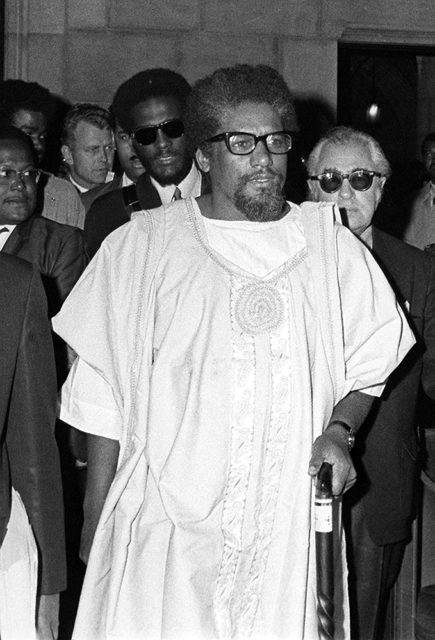

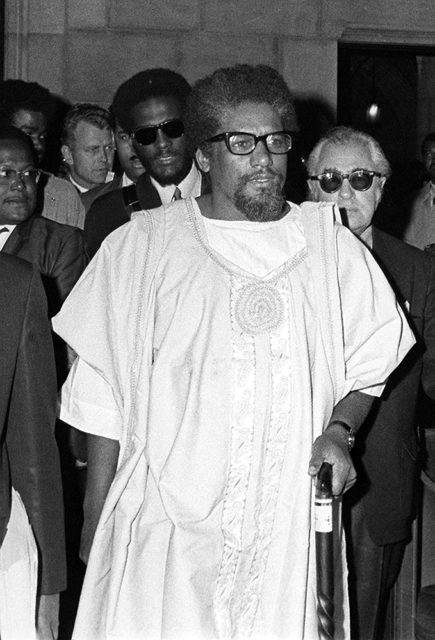

Activist James Forman walks in New York’s Riverside Church on May 11, 1969. Forman returned to the church after interrupting a service there earlier that month to deliver the Black Manifesto. (AP Photo)

The manifesto was quite specific in its demands. Black activists would control the distribution of reparations. The $500 million (soon increased to $3 billion) would be spent on programs designed to ensure black self-determination. These included establishing a Southern land bank, publishing industries, television networks, job training centers, labor unions and a black university.

The manifesto’s rhetoric was just as controversial. Written by Forman, a former member of the civil rights group known as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the preamble framed reparations in Marxist terms. “Time is short,” Forman wrote. “(N)o oppressed people ever gained their liberation until they were ready to fight, to use whatever means necessary, including the use of force and power of the gun to bring down the colonizer.”

Prominent black and white religious leaders diverged on how to interpret Forman’s call for revolution. The Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, who succeeded the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, compared Forman to biblical prophets who spoke truth to power. Writing in The Christian Century, he asked, “Was there not even a physical resemblance between Amos, the dusty-road-weary prophet in his desert garb, and Jim Forman in his dashiki?”

The response from some white denominations was outright rejection. The Southern Baptist Convention dismissed the manifesto as “outrageous.” The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York called it un-American and touted its own programs for the “needy and disadvantaged” instead.

The American Jewish Committee, which as part of the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization had helped organize the National Black Economic Development Conference, withdrew from the IFCO. Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum, IFCO’s first president, resigned, stating he could not “in conscience stand by in silence and appear … to give assent to the revolutionary ideology and racist rhetoric of the Black Manifesto.”

Other denominations were more ambivalent. The Reformed Church in America invited Forman to address its general synod after he occupied the denomination’s headquarters a month after his action at Riverside. The Rev. Rand Peabody, a 22-year-old white seminarian who had already been slated to give the sermon the next day, revised his sermon after hearing news of Forman’s “liberation” of the RCA’s offices.

The Rev. Rand Peabody. Courtesy photo

“I remember I said it’s not a time for us to feel either blamed or shamed and certainly not a time to feel futile,” Peabody, now 73, said in an interview. “Our denomination, in his eye, did indeed have the power to play a part and we should accept that as almost a commissioning of the denomination to indeed step up to the plate and get involved in more focused and proactive ways.”

Like other denominations, the RCA didn’t accede to Forman’s demand that reparations be handed over freely. Instead the synod voted to create a $100,000 fund “to be disbursed according to the decisions” of a newly formed Black Council. The council then rejected the money.

“We just basically wanted to be at the table where decisions are being made and not considered an auxiliary or an offshoot or a secondhand portion of the denomination,” said the Rev. Dwayne Jackson, a Hackensack, New Jersey, pastor, who was a panelist at an RCA event commemorating the manifesto in October titled “Unfinished Business.”

Jackson, who knew some members of the council from his childhood church in the Bronx, said the staffer hired to oversee the council was the church’s first black executive. (Today, people of color comprise a third of the RCA’s executive leadership team.)

Other denominations acknowledged the grievances raised by the manifesto but rejected the solutions it proposed and even the language of “reparations.” Instead they created or continued programs aimed at helping poor blacks and others. The Presbyterian Committee on the Self-Development of People, the Evangelical Covenant Church’s Fund for Disadvantaged Americans of Minority Groups and the Episcopal Church’s General Convention Special Program were all created around the time of Forman’s action.

Dominique DuBois Gilliard, the current director of the ECC’s “racial righteousness and reconciliation” ministry, recently reflected on how this kind of response “enacted a very problematic erasure of the black freedom struggle.”

Met with the manifesto’s demands, “the Covenant found it more palatable to shift the conversation to marginalization in general,” Gilliard writes in the May/August edition of its Covenant Quarterly, which focused on the 50th anniversary of the manifesto. “This response has strong parallels to proclamations that ‘All Lives Matter’ in response to the declaration ‘Black Lives Matter.’”

There has been a shift in recent years, however, which Gilliard has helped encourage. The ECC Resolution on Racism, passed in June, insists that “the time is right for white clergy to attend to the sins of our own community and make a public commitment to prioritize antiracism work within our ministerium.”

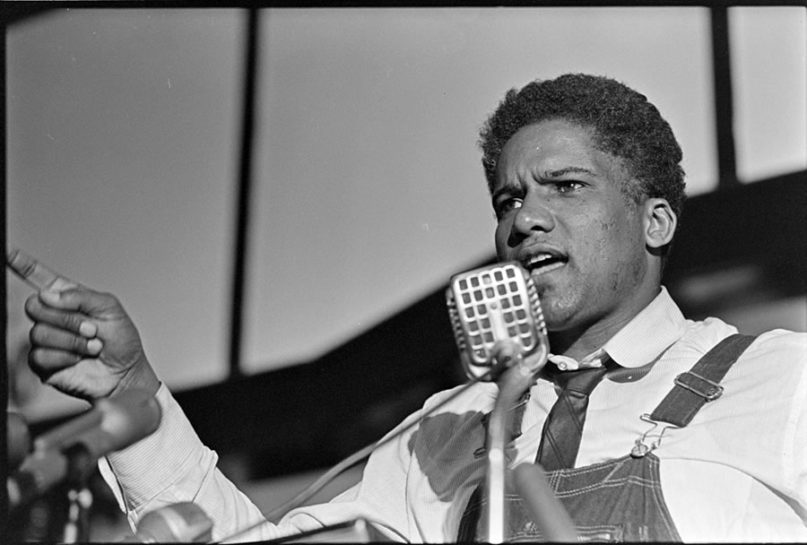

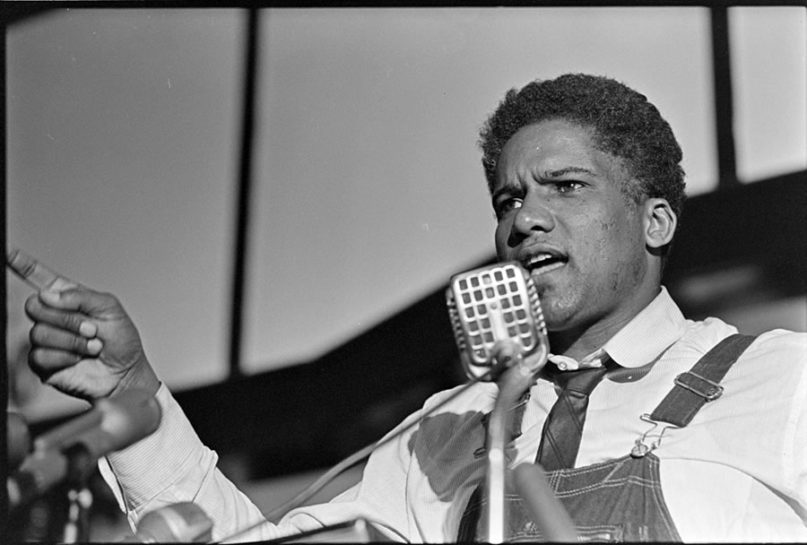

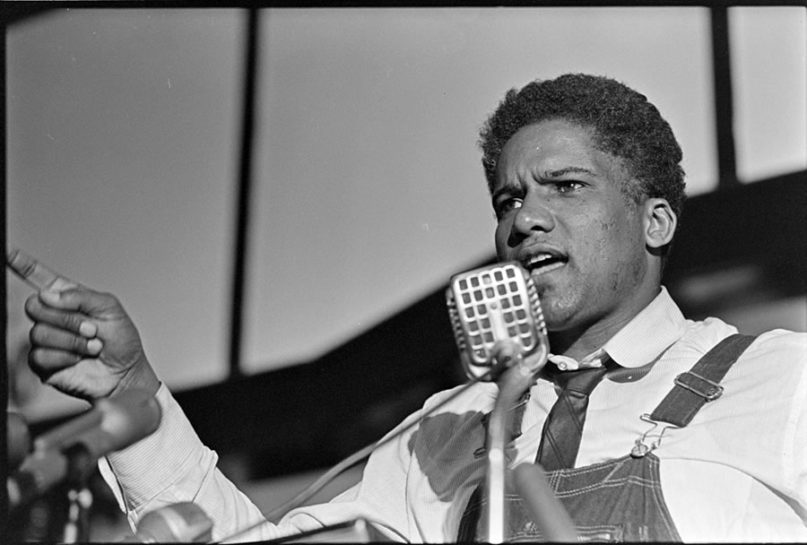

Activist James Forman speaks in Montgomery, Alabama, in March 1965. Photo by Glen Pearcy/Library of Congress/Creative Commons

Nell Gibson, a member and former chair of the Episcopal Diocese of New York’s Reparations Committee, recalled that in the wake of Forman’s declaration — which resulted in the Episcopal Church’s $200,000 donation to the National Committee of Black Churchmen — members of her Manhattan church created a Black and Brown Caucus. After receiving the $30,000 they demanded from their St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, they developed a free breakfast program for children, a summer “liberation school” that taught minority children their ancestors’ history and a prison law library.

Fifty years on, reparations are often framed as spiritual tests as much as financial ones. This year was named the “Year of Apology” for the Episcopal Diocese of New York, and each Sunday Gibson’s congregation has said a prayer that includes this sentence: “For the many ways — social, economic and political — that white supremacy has accrued benefits to some of us at the expense of others, we repent.”

Soon, the diocesan reparations committee will consider a number of possible next steps, such as a truth and reconciliation commission or education and health care initiatives.

Likewise, Sutton said his Maryland Episcopal diocese is moving methodically after years of conversation about reparations to figuring out how that will be lived out financially and otherwise.

“We don’t have all the solutions, we don’t know everything that’s going to fix the problem and so we’re going to be humble in even what we think we can accomplish,” he said. “But, by God, we’re going to do something.”

by Matthew J. Cressler and Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jan 2, 2020 | Headline News |

James Forman, chief spokesman for the Black Manifesto, inspects a bulletin board in New York’s Interchurch Center after he and supporting members of the National Black Economic Development Conference seized three floors of offices in 1969. The NBEDC sought $500 million in reparations from the white religious community. RNS file photo

On a Sunday morning in May of 1969, as clergy processed into the sanctuary of New York’s august Riverside Church, civil rights activist James Forman vaulted into the pulpit to demand $500 million in reparations for the mistreatment of African Americans from white churches and synagogues.

At the time, Forman’s interruption represented the high point for the reparations movement. A week before, Forman had debuted a radical proposal for racial justice known as “the Black Manifesto” for 500 black activists gathered in Detroit for the National Black Economic Development Conference.

“(W)e know that the churches and synagogues have a tremendous wealth,” the manifesto stated, “and its membership, white America, has profited and still exploits black people.”

The conference determined, by a 187-63 vote, that it was time for white Christians and Jews to pay reparations and demonstrate a willingness to fight “the white supremacy and racism which has forced us as black people to make these demands.”

Riverside, then a mostly white liberal Protestant congregation whose neo-Gothic landmark building was financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr., would be deeply divided over the next few years over Forman’s challenge. As the activist brought his manifesto to other congregations and denominations, Riverside established a lecture series and a “Fund for Social Justice” that aimed to raise $450,000 over three years to help the poor in the local community. It fell short of the goal by almost $100,000.

Members of the congregation file out after Sunday morning worship services at Riverside Church in New York on July 20, 2014. The building is modeled after the 13th-century cathedral in Chartres, France. (AP Photo/Kathy Willens)

The Black Manifesto’s demands never caught fire in the broader U.S. religious community. The Rev. Gayraud Wilmore, a black Presbyterian leader in New York City in 1969, recalled 50 years later how religious institutions responded.

“I saw them withering and unable to step forward and say ‘Let’s be the church,’” said Wilmore, now 98. “I saw no bold action taken on our side to go along with the bold action Forman was taking.”

Five decades later, the reparations debate has re-entered the national spotlight, with some religious institutions leading the way.

Earlier in December, Reform Jews, declaring that “racial inequity is present in virtually every aspect of American life,” voted overwhelmingly to support a U.S. commission to develop proposals for reparations and urged conversations in their congregations to redress systemic racism.

In recent months, Virginia Theological Seminary, Princeton Theological Seminary and Georgetown University have all announced plans to fund initiatives that would benefit the descendants of slaves, while Episcopal dioceses in New York and Long Island made million- and half-million-dollar commitments as reparations committees continued their work.

In May, the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland voted to study reparations and urge congregations to “examine how their endowed wealth is tied to the institution of slavery.”

Maryland Episcopal Bishop Eugene Sutton testifies before the U.S. Congress about reparaions in June 2019. Video screengrab via C-SPAN

Maryland’s African American bishop, Eugene Taylor Sutton, said tears came to his eyes when the measure passed at the diocese’s general convention with no dissenting votes, and he realized that the assembled delegates, representing a membership that is 90% white, “got it.”

“They get this thing called justice, and when you put it in a frame that there is a basic injustice in this nation of stealing from generations of people and that has a direct effect on today, then people,” Sutton said, “they say, ‘OK, we got to get that fixed.’”

Sutton, who testified before Congress in June with writer Ta-Nehisi Coates to advocate for the idea of a U.S. reparations commission, emphasized that reparations can come in many forms. Starting next month, members of his diocese will begin to consider options such as providing better access for people of color to home buying, job training and faculty positions at seminaries.

It has taken some American religious institutions 50 years to get their heads around reparations. When Forman hijacked that Sunday morning service, two-thirds of Riverside worshippers, including the minister, stormed out in protest. After activists occupied offices in the Interchurch Center of New York, a court-issued restraining orders to bar Forman from the building. In Missouri, manifesto supporters in St. Louis carried out a series of “Black Sunday” protests, interrupting local services, which led to confrontations with white church members and arrests.

Activist James Forman walks in New York’s Riverside Church on May 11, 1969. Forman returned to the church after interrupting a service there earlier that month to deliver the Black Manifesto. (AP Photo)

The manifesto was quite specific in its demands. Black activists would control the distribution of reparations. The $500 million (soon increased to $3 billion) would be spent on programs designed to ensure black self-determination. These included establishing a Southern land bank, publishing industries, television networks, job training centers, labor unions and a black university.

The manifesto’s rhetoric was just as controversial. Written by Forman, a former member of the civil rights group known as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the preamble framed reparations in Marxist terms. “Time is short,” Forman wrote. “(N)o oppressed people ever gained their liberation until they were ready to fight, to use whatever means necessary, including the use of force and power of the gun to bring down the colonizer.”

Prominent black and white religious leaders diverged on how to interpret Forman’s call for revolution. The Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, who succeeded the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, compared Forman to biblical prophets who spoke truth to power. Writing in The Christian Century, he asked, “Was there not even a physical resemblance between Amos, the dusty-road-weary prophet in his desert garb, and Jim Forman in his dashiki?”

The response from some white denominations was outright rejection. The Southern Baptist Convention dismissed the manifesto as “outrageous.” The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York called it un-American and touted its own programs for the “needy and disadvantaged” instead.

The American Jewish Committee, which as part of the Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization had helped organize the National Black Economic Development Conference, withdrew from the IFCO. Rabbi Marc H. Tanenbaum, IFCO’s first president, resigned, stating he could not “in conscience stand by in silence and appear … to give assent to the revolutionary ideology and racist rhetoric of the Black Manifesto.”

Other denominations were more ambivalent. The Reformed Church in America invited Forman to address its general synod after he occupied the denomination’s headquarters a month after his action at Riverside. The Rev. Rand Peabody, a 22-year-old white seminarian who had already been slated to give the sermon the next day, revised his sermon after hearing news of Forman’s “liberation” of the RCA’s offices.

The Rev. Rand Peabody. Courtesy photo

“I remember I said it’s not a time for us to feel either blamed or shamed and certainly not a time to feel futile,” Peabody, now 73, said in an interview. “Our denomination, in his eye, did indeed have the power to play a part and we should accept that as almost a commissioning of the denomination to indeed step up to the plate and get involved in more focused and proactive ways.”

Like other denominations, the RCA didn’t accede to Forman’s demand that reparations be handed over freely. Instead the synod voted to create a $100,000 fund “to be disbursed according to the decisions” of a newly formed Black Council. The council then rejected the money.

“We just basically wanted to be at the table where decisions are being made and not considered an auxiliary or an offshoot or a secondhand portion of the denomination,” said the Rev. Dwayne Jackson, a Hackensack, New Jersey, pastor, who was a panelist at an RCA event commemorating the manifesto in October titled “Unfinished Business.”

Jackson, who knew some members of the council from his childhood church in the Bronx, said the staffer hired to oversee the council was the church’s first black executive. (Today, people of color comprise a third of the RCA’s executive leadership team.)

Other denominations acknowledged the grievances raised by the manifesto but rejected the solutions it proposed and even the language of “reparations.” Instead they created or continued programs aimed at helping poor blacks and others. The Presbyterian Committee on the Self-Development of People, the Evangelical Covenant Church’s Fund for Disadvantaged Americans of Minority Groups and the Episcopal Church’s General Convention Special Program were all created around the time of Forman’s action.

Dominique DuBois Gilliard, the current director of the ECC’s “racial righteousness and reconciliation” ministry, recently reflected on how this kind of response “enacted a very problematic erasure of the black freedom struggle.”

Met with the manifesto’s demands, “the Covenant found it more palatable to shift the conversation to marginalization in general,” Gilliard writes in the May/August edition of its Covenant Quarterly, which focused on the 50th anniversary of the manifesto. “This response has strong parallels to proclamations that ‘All Lives Matter’ in response to the declaration ‘Black Lives Matter.’”

There has been a shift in recent years, however, which Gilliard has helped encourage. The ECC Resolution on Racism, passed in June, insists that “the time is right for white clergy to attend to the sins of our own community and make a public commitment to prioritize antiracism work within our ministerium.”

Activist James Forman speaks in Montgomery, Alabama, in March 1965. Photo by Glen Pearcy/Library of Congress/Creative Commons

Nell Gibson, a member and former chair of the Episcopal Diocese of New York’s Reparations Committee, recalled that in the wake of Forman’s declaration — which resulted in the Episcopal Church’s $200,000 donation to the National Committee of Black Churchmen — members of her Manhattan church created a Black and Brown Caucus. After receiving the $30,000 they demanded from their St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, they developed a free breakfast program for children, a summer “liberation school” that taught minority children their ancestors’ history and a prison law library.

Fifty years on, reparations are often framed as spiritual tests as much as financial ones. This year was named the “Year of Apology” for the Episcopal Diocese of New York, and each Sunday Gibson’s congregation has said a prayer that includes this sentence: “For the many ways — social, economic and political — that white supremacy has accrued benefits to some of us at the expense of others, we repent.”

Soon, the diocesan reparations committee will consider a number of possible next steps, such as a truth and reconciliation commission or education and health care initiatives.

Likewise, Sutton said his Maryland Episcopal diocese is moving methodically after years of conversation about reparations to figuring out how that will be lived out financially and otherwise.

“We don’t have all the solutions, we don’t know everything that’s going to fix the problem and so we’re going to be humble in even what we think we can accomplish,” he said. “But, by God, we’re going to do something.”