Saved and Depressed: A Real Conversation About Faith and Mental Health

Video courtesy of CBN News

Republished in honor of Mental Health Awareness Month.

When you see a man walking down the street talking to himself, what is your first thought? Most likely it’s, “He is crazy!” What about the lady at the bus stop yelling strange phases? You immediately become guarded and move as far away from her as possible. I know you’ve done it. We all have.

We are so quick to judge others on the surface level without taking the time to think that maybe God is placing us in a situation for a reason. Maybe it is a test and in order to pass, you must show love and compassion for something or someone that you do not understand.

Perhaps the man or woman you judge are suffering from a mental illness. However, do not be deceived by appearances, because mental illness does not have “a look.”

More Than What Meets The Eye

When most people look at me, they see a successful, 20-something-year-old woman who is giving of herself and her time. In the past, they would only see a bubbly, out-going, praying and saved young lady who is grounded in her faith. When outsiders look at me, they often see someone with two degrees from two of America’s most prestigious institutions, an entrepreneur who prides herself on inspiring others to live life on purpose, and simply lets her light shine despite all obstacles.

However, what so many do not know is that there was a time when I was dying on the inside. On a beautiful summer morning, at the tender age of 25, I suddenly felt sick. It was not the kind of sick where one is coughing with a fever and chills. I felt as if there were a ton of bricks on top of my body and I could not move my feet from the bed to the floor.

Then, there were times when I was unable to stop my mind from racing. I had a hard time concentrating on simple tasks and making decisions. My right leg would shake uncontrollably and I would get so overwhelmed by my mind.

It was in those moments when I inspired to begin researching depression and anxiety. I had the following thoughts as I read the symptoms: “This sounds like me. But, if I’m diagnosed with depression and anxiety, does this mean I am no longer grounded in my faith? Would I walk around claiming something that the Christians deemed as not being a “real” disease? Am I speaking this illness into existence?”

Who Can I Turn To?

According to the National Association of Mental Illness (NAMI), Depression is a chemical imbalance in the brain and mood disorder that causes persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, guilt and one cannot “just snap out of it.”

NAMI also describes anxiety as chronic and exaggerated worrying about everyday life. This can consume hours each day, making it hard to concentrate or finish routine daily tasks.

As the months passed, my symptoms became progressively worse and I became so numb to life. I slowly began to open up to my church family and some of the responses I received were so hurtful. I received a variety of suggestions on everything from speaking in tongues for 20 minutes to avoiding medication because it would make my condition worse.

As a result, I did not know what to do. I felt lost and alone, because a community that I turned to first in my time of trial and tribulation did not understand me. I was so deep in my depression that praying and reading my Bible was too difficult of a task to complete.

As time went on, I eventually went to the doctor and guess what? I was right. I went undiagnosed for over 10 years. Imagine the consequences if a person with cancer, AIDS/HIV or diabetes went undiagnosed.

The Breaking Point

I eventually found myself in the hospital after a friend called 911 to notify them of my suicide attempt. I was so removed from life that when the doctor asked me the day of the week and date, I could not tell him.

Honestly, I can tell you a number of reasons why I tried to commit suicide. Some of them were external factors, such as finances. Some of it was burn-out. Some of it was unresolved childhood issues and genetics.

However, after learning my family medical history, I discovered that several members of my family battled mental illness during their lifetime. Both of my parents battled mental illness, and my grandfather informed me about the time he tried to commit suicide at the age of 14. My uncle was admitted to the hospital due to schizophrenia.

A Bright Future

Over time, I’ve come to the conclusion that I have no reason to feel ashamed or embarrassed. God has placed amazing people in my life from family members, friends who are simply extended family, doctors, therapists, and medication.

While my goal is not to rely on medication for the rest of my life, I am grateful that I found something that works while I work through recovery. Looking back to where I was about two years ago, I would have never saw myself living life with depression and anxiety.

I believe in the power of prayer and God’s word. As the scripture states in James 2:17, “Faith by itself isn’t enough. Unless it produces good deeds, it is dead and useless.” This leads me to believe that no matter how difficult the situation is, I will have to work towards healing and recovery even though I have a strong foundation and faith.

Do you have words of encouragement for someone who is battling mental illness? Share your thoughts below.

Lied to and abused, trafficked persons from Zimbabwe find some healing

Religious sisters attend the Regional Conference on Human Trafficking, March 18 at Arrupe Jesuit University in Harare, Zimbabwe. Center: Sr. Theresa Nyadombo of the Handmaids of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, education secretary for the Zimbabwe Catholic Bishops’ Conference, said a collaborative effort is needed to raise human trafficking awareness. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

This article originally appeared on The Global Sisters Report

HARARE, ZIMBABWE — Jane sat on a hard, wooden chair at a church in Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare, and stared into space for some minutes. Then, she began to croon in worship and, a few minutes later, the gates of her heart burst open, and she began to pour out her heart to her Lord, tears flowing freely like a fountain.

“Father, I forgive my abusers and the people who caused me pain,” prayed the 37-year-old mother of two, who asked that Global Sisters Report not use her real name. “They treated me like an animal, like I didn’t matter, like I was a dog, worse than a dog. God, please heal my pain and heal my broken heart.”

Jane’s journey of pain began in 2016, when she was enticed by a trafficking agent in Harare with promises of a salary of $1,400 per month at a hotel in Kuwait, more than 3,000 miles away. Life had become unbearable in Zimbabwe after her husband lost his job as a casual laborer in a local milk factory and they were evicted from their house for nonpayment of rent.

“Life was very difficult and we barely had something to eat, and if we ate, it was one meal per day,” she said.

It was at this difficult time that she met her trafficker, who was well acquainted with her mother. Everything was planned quickly, and within one week, all her travel documents were ready, including her passport. She was given a new Islamic name: Amina Ishmael.

Religious sisters display cloth promoting work against human trafficking at the Regional Conference on Human Trafficking, March 18 at Arrupe Jesuit University in Harare, Zimbabwe. The conference was organized by the African Forum for Catholic Social Teaching and brought together various activists in the area of human trafficking. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

Upon reaching Kuwait, she was picked up from the airport by a man who would be her boss. It was at his house that Jane realized she had been lied to and trafficked. Her host took away her travel documents and forcefully performed a medical procedure to check her overall health.

“I was raped every day, and I was helpless to do anything about it,” she said, weeping throughout the interview with GSR but insisting she wanted to tell her story. “I was forced to work day and night, beaten, restricted to go anywhere, threatened of arrest and deportation and unlawful withholding of my passport. I wasn’t even paid for the five months I worked at the home.”

When things became intolerable, she fled the home and took refuge in the Zimbabwe consulate. Jane was deported after a week, and upon arrival back in Zimbabwe, she was introduced to the religious sisters who run the African Forum for Catholic Social Teaching (AFCAST), an association of justice and peace practitioners throughout Africa, and who chaired the Counseling Services Unit, a group of doctors and counselors who assist the victims of human trafficking in Zimbabwe.

“As AFCAST, we deal with social problems that affect the people,” said Sr. Janice McLaughlin of the Maryknoll Sisters, who is one of the forum’s founders. “We focus our attention mainly on human trafficking and abuse of children and vulnerable adults. We always do our research and then we try to reach out to those affected or those we feel need help. All this is done by following Catholic social teaching and mission.”

Maryknoll Sr. Janice McLaughlin, one of the founders of the African Forum for Catholic Social Teaching, leads dozens of sisters in denouncing trafficking during the Regional Conference on Human Trafficking, March 18 at Arrupe Jesuit University in Harare, Zimbabwe. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

‘There are no jobs here’

Jane is among the 40.3 million people who have been trafficked globally, including 24.9 million in forced labor and 15.4 million in forced marriage, according to 2016 estimates by the International Labor Organization, the most recent available data.

Human trafficking in Africa is an urgent crisis, and women and children are especially at risk. People can be trafficked within their own countries, to neighboring countries and to other continents for sexual exploitation, sexual slavery, forced marriage, domestic slavery and various forms of forced labor, according to the latest report by the United Nations.

Zimbabwe does not meet the minimum standards for eliminating human trafficking but is making significant efforts to do so, according to the 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report from the U.S. State Department. The report also notes that the southern African nation has been mapped as a source, destination and transit point for trafficking. In most of these cases, victims are vulnerable children and young adults.

In 2014, the Zimbabwe Parliament passed the Trafficking in Persons Act to identify those who have been trafficked, mitigate the illicit practice and prosecute trafficking offenders. However, it wasn’t until 2016 that the government launched the Trafficking in Persons National Plan of Action to enforce the law.

Since then, Zimbabwe’s government has made some headway in its efforts to end human trafficking. It investigated 72 potential cases of trafficking and prosecuted 42 cases in 2016, compared to none in the previous year. The government reported prosecuting 14 trafficking cases in 2017.

However, women and girls from Zimbabwean towns bordering South Africa, Mozambique and Zambia are still trafficked and subjected to forced labor and prostitution. In rural areas, men, women and children are also trafficked internally to farms for agricultural labor and to cities for forced domestic labor and commercial sexual exploitation, according to the U.S. State Department.

Along Robert Mugabe Road in Harare earlier this year, hundreds of young female travelers stood in queue, holding luggage and waiting for their turn to enter into a bus. The driver of the Citiliner bus, a South African coach company offering services from Harare to Johannesburg, told GSR that many of them were heading to neighboring South Africa to look for greener pastures.

One of them, a young blond woman in a navy dress, told GSR she felt there was no future for her in her home of Bulawayo in southwest Zimbabwe, and she was seeking opportunities in South Africa to help educate her siblings. She said her friend living in the United States had put her into contact with a woman in Johannesburg who promised to use her connections to find her a well-paying job as a maid.

She blamed poverty and lack of jobs in the country as a reason of migration. The World Bank estimates that extreme poverty in Zimbabwe has risen over the past few years, from 33.4% of the population in 2017 to 40% in 2019. The bank predicts levels will continue to rise in 2020, to between 6.6 million and 7.6 million people. That is about half of the people in this country, who are living on less than $1.90 per day.

“I have no choice but to go and try my luck,” the woman said on condition of anonymity, noting that she doesn’t even have regular migration documents. “I’m told that one needs to have at least $30 to bribe border officials, then they will let you in. There are no jobs here, so I have to try elsewhere to earn a living and help my family.”

High school students attend the Regional Conference on Human Trafficking, March 18 at Arrupe Jesuit University in Harare, Zimbabwe. Public education and awareness campaigns were launched to help especially children, since they are the most vulnerable. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

How the sisters and AFCAST help

On the streets of Harare, people jostle for space to get a glimpse of some notice boards advertising jobs and vacancies in the Middle East, North Africa and in Italy, Spain and other European countries. The vacancies on the glass-sealed notice boards are for recruitment agents looking for saleswomen, housekeepers, hotel attendants, drivers, waitresses and chefs.

Such practices that lead to trafficking have prompted religious sisters in the country and elsewhere to stand up against it. They have been organizing workshops every month in schools and churches to create awareness and assist women and girls affected by trafficking.

McLaughlin said the African Forum for Catholic Social Teaching assists women and girls affected by human trafficking with counseling, reuniting them with their families and even helping them start self-help projects.

“I was really moved by the plight of young women and girls trafficked to Kuwait and other Gulf states when I met some of them through the migration office,” she said. “They are abused in foreign countries after being promised lucrative job offers. But it has been really rewarding to see some of them heal from trauma.”

While addressing a regional conference on human trafficking March 18 at the Arrupe Jesuit University in Harare, McLaughlin denounced human trafficking as dehumanizing.

“Human trafficking is destroying the lives of many people, especially young people and young women. Therefore, there is need for a collective effort to fight the vice,” she said.

The conference, which was organized by the African Forum for Catholic Social Teaching in partnership with the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom, brought together various organizations involved in fighting human trafficking: the governments of Zimbabwe and the United States; survivors of trafficking; faith leaders, including Muslims; and members of civil society.

Sr. Mercy Shumbamhini of the Mary Ward Congregation of Jesus in Zimbabwe holds a Talitha Kum banner during the Regional Conference on Human Trafficking, March 18 in Harare, Zimbabwe. Talitha Kum is a Rome-based organization of Catholic women religious established by the International Union of Superiors General in 2009 to end human trafficking. (GSR photo/Doreen Ajiambo)

“It is the responsibility of each one of us to fight human trafficking,” said Maria Phiri, a detective representing the Zimbabwe Republic Police. “I would like therefore to encourage everyone to collaborate in this fight by detecting any suspicious activities and also report cases of human trafficking to the authorities.”

Human trafficking has disturbing and long-lasting effects on mental health, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, anger, guilt and shame.

Sr. Elizabeth Boroma, a psychologist, has been counseling women and girls who have been trafficked for sexual exploitation, domestic servitude and forced labor. Boroma told GSR she has helped hundreds of women to come to terms with their pasts and to face their futures with confidence and dignity.

“Most of them are always hesitant at first to talk about their experiences, but with time, they open up and release it,” said Boroma of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur. “Some usually cry throughout the entire counseling session, and I let them do it because it’s their way of healing.”

Sarah is one the beneficiaries of Boroma’s counseling service. She recounts heartbreaking tales of desperation, rape, hunger, life on the streets and the suffering she endured in the hope of a better life four years ago in Saudi Arabia, where she thought opportunities were better.

“I wanted take away my life because of the bad experience I went through while in Saudi Arabia,” said the 28-year-old mother of one, who asked GSR not to use her real name. “I went through therapy with the help of the nun, and it helped me move on quickly. I’m now happily married and doing a grocery delivery business.”

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has changed the nature of the sisters’ anti-trafficking work. Victims of human trafficking say they are not getting the personalized, face-to-face counseling and interaction they previously enjoyed with the sisters. They are also dealing with the loss of their livelihoods.

The sisters have adopted new ways of providing the needed follow-up counseling by communicating with the young women via WhatsApp, email, texting and phone calls.

Jane is still suffering from the sexual assault she went through while in Kuwait and hopes to attend several months of therapy to help her heal and move on.

“I want to move on, but it’s hard to forget what the man did to me,” she said. “He treated me like an animal, but I leave everything to God.”

[Doreen Ajiambo is the Africa/Middle East correspondent for Global Sisters Report. Follow her on Twitter: @DoreenAjiambo.]

7 lessons from NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson’s life and career

AP Photo/Chris Pizzello

Katherine Johnson, an African-American mathematician who made critical contributions to the space program at NASA, died Feb. 24 at the age of 101.

Johnson became a household name thanks to the celebrated book “Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians who Helped Win the Space Race,” which later became a movie. Her legacy provides lessons for supporting women and other underrepresented groups in mathematics and science.

As a historian of mathematics, I have studied women in that field and use the book “Hidden Figures” in my classroom. I can point to some contemporary ideas we can all benefit from when examining Johnson’s life.

1. Mentors make a difference

Early in her life, Johnson’s parents fostered her intellectual prowess.

Because there was no high school for African-American children in their hometown of White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, the family relocated to Institute, West Virginia, during the school year. Johnson entered West Virginia State College High School as a preteen and enrolled at the age of 14.

While at West Virginia State, Johnson took classes with Angie Turner King. King taught at the laboratory high school while she worked to become one of the first African-American women to earn masters degrees in math and chemistry. She would go on to earn a Ph.D. in math education in 1955.

King taught Johnson geometry and encouraged her mathematical pursuits. Thirteen years older than Johnson, she modeled a life of possibility.

Johnson graduated from West Virginia State College at the age of 18. While there, she had the good fortune to learn from W. W. Schieffelin Claytor, the third African American to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics in America. Claytor encouraged Katherine to become a research mathematician. In the 1930s, a little over 100 American women counted themselves as professional mathematicians.

AP Photo/Evan Vucci

2. High school mathematics adds up

Once Johnson completed the standard mathematics curriculum at West Virginia State College, Claytor created advanced classes just for her, including a course on analytic geometry.

Mathematics concepts build on one another and the mathematics she learned in this class helped her in her work at NASA many years later. She used these analytical skills to verify the computer calculations for John Glenn’s orbit around the earth and to help determine the trajectory for the 1969 Apollo 11 flight to the moon, among others.

3. Grit matters

Long before psychologist Angela Duckworth called attention to the power of passion and perseverance in the form of grit, Katherine Johnson modeled this stalwart characteristic.

In 1940, she agreed to serve as one of three carefully selected students to desegregate West Virginia University’s graduate program. She also had to be “assertive and aggressive” about receiving credit for her contributions to research at NASA.

In 1960, her efforts helped her become the first African-American and the first woman to have her name on a NASA research report. Currently, the NASA archives contain more than 25 scientific reports on space flight history authored or co-authored by Johnson, the largest number by any African-American or woman.

4. The power of advocating for yourself

NASA, CC BY

When NASA was formed in 1958, women were still not allowed to attend the Test Flight briefings.

Initially, Johnson would ask questions about the briefings and “listen and listen.” Eventually, she asked if she could attend. Apparently, the men grew tired of her questions and finally allowed her to attend the briefings.

5. The power of a team

In 1940, Johnson found herself among the 2% of all African-American women who had earned a college degree. At that time, she was among the nearly 60% of those women who had become teachers.

Later, she joined the West Computing Group at Langley Research Center where women “found jobs and each other.” They checked each other’s work and made sure nothing left the office with an error. They worked together to advance each other individually and collectively as they performed calculations for space missions and aviation research.

AP Photo/NASA

6. The power of women advocating for women

Although Johnson started as a human computer in the West Computing Group, after two weeks she moved to the Maneuver Load Branch of the Flight Research Division under the direction of Henry Pearson.

When it was time to make this position permanent after her six month probationary period,

Dorothy Vaughan, then the West Computing department head and Johnson’s former boss, told Pearson to “either give her a raise or send her back to me.” Pearson subsequently offered Johnson the position and the raise.

7. The legacy of possibility

In March of 2014, Donna Gigliotti, producer of Shakespeare in Love and The Reader, received a 55-page nonfiction proposal about African-American women mathematicians at NASA in Hampton, Virginia.

“I kind of couldn’t get over the fact that this was a true story and I didn’t know anything about it,” Gigliotti confessed. “I thought well, this is a movie.” Gigliotti’s hunch ultimately led to the movie “Hidden Figures” and an entire generation of young people learning about the possibilities of math and science.

The U.S. State Department showed Hidden Figures throughout the developing world to encourage girls and women to consider the possibilities of careers in math and science. Mattel created a Katherine Johnson Barbie in its “Inspiring Women” series to celebrate “the achievements of a pioneer who broke through the barriers of race and gender.”

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]![]()

Della Dumbaugh, Professor of Mathematics, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Slave life’s harsh realities are erased in Christmas tours of Southern plantations

Shreveport-Bossier Convention and Tourist Bureau/Flickr, CC BY

Robert E. May, Purdue University

This holiday season, many Americans will tour historic mansions in the Southern United States that are beautifully decked out in traditional wreaths, garlands and mistletoe for Christmas.

At Mount Vernon, George Washington’s Virginia mansion, tourists are promised candlelit tours and a “festive evening” of refreshments, 18th-century dancing and more. Visitors can even meet a re-enactor playing Martha Washington, America’s First Lady.

At the state-run Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantation Historic Site in Brunswick, Georgia, promoters promise attendees a “magical experience” during the holiday event, learning how “Christmas was celebrated on a Southern rice plantation during the 1850s.”

What these tours teach is how rich white Southerners once celebrated Christmas: singing Christmas carols, dancing, drinking the cider brew wassail and enjoying refreshments or formal meals.

Few make a serious effort to tell what Christmas was like for the enslaved workers at these plantations before the American Civil War.

What’s missing?

When the black historian Brandon Byrd visited Belle Meade, a mansion in Nashville, Tennessee, for its Christmas tour a few years ago, he was shocked that the slave community and their harsh realities were barely mentioned. Instead, he reported, the tour guide mostly related “stories about the white men, women and children who woke up to Christmas in the mansion’s plush bedrooms.”

By the American Civil War, nearly four million slaves in all toiled in the southern states, and about a million lived as servants in mansions and as field hands on large plantations with 50 slaves or more. They did almost all the grueling household and field labor that kept these places going, often sleeping and cooking in primitive cabins and working in unhealthy conditions under the threat of the whip.

In fact, the historic mansions hosting Christmas tourists never would have been built without the profits generated by slave labor. The grand Nottoway Plantation and resort in Louisiana, which traditionally puts on a Christmas event, was constructed just before the Civil War by some 155 slave workers.

Fictional tales and memoirs

In researching my 2019 book “Yuletide in Dixie,” I discovered that many historic plantation and mansion sites are reluctant to talk about slavery at their Christmas events. This is partly because administrators want to avoid topics that might make paying guests angry or uncomfortable.

But the omission of black southerners from these holiday tales also stems from pervasive myths about slave life at southern plantations before the Civil War.

For a long time, many people got their ideas about slavery at these places from memoirs, novels and short stories written by white southerners after the Civil War. These stories, now outrageous for their racial stereotypes, not only justified the institution of slavery, they also made it seem like all enslaved people had fun on a southern plantation at holiday time, dancing, singing, laughing and feasting for the holiday season, just as their masters did.

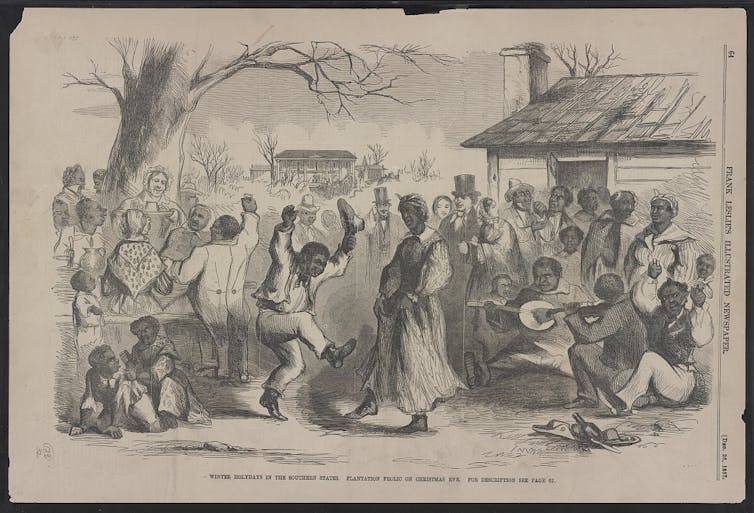

Frank Leslie, in 1857

Susan Dabney Smedes, a white girl who grew up on a Mississippi plantation, published a memoir in 1887 called “Memorials of a Southern Planter” that made slave Christmases sound like wonderful times. Smedes wrote about how slaves wore their best clothes for Christmas, played a word game called “Christmas Gif’” with their white enslavers and drank eggnog their master made for them.

In a fictional tale published in the “Century Magazine” in 1911, an enslaved carpenter named Jerry even turns down the freedom that his master offers him on Christmas because he likes his life as a slave so much, and especially the Christmas present his master specially picks out for him each year.

Many of these memoirs and preposterous short stories and novels about happy slave Christmas experiences were so popular that they were republished in new editions over and over again from the late 1800s and early 1900s until, in some cases, the present.

Smedes’s “Memorials of a Southern Planter” was regularly republished for a century after its first appearance.

Many Americans got falsely pleasant images of slavery and especially slave Christmases from reading these works, and these wrongful impressions not only affected how the public thought and still thinks about slavery but, more specifically, how site administrators at southern historic mansions and plantations planned their Christmas programs.

Whipped and sold on Christmas

I read many documents to find out how slaves actually spent their Christmases. The truth is deeply disturbing.

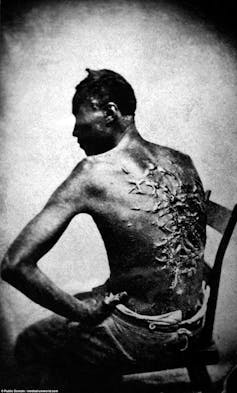

Mediadrumworld.com

On the one hand, the majority of enslaved people did get some them time off from work during Christmas, as well as feasts and presents. Some got to travel or to get married, privileges that they didn’t get at other times of the year. But these privileges could be withdrawn for any reason at all and many slaves never got them at all.

Slavery was a brutal system of forced labor to enrich those same owners. Even over the holiday, masters kept the power to punish slaves. A photo taken during the Civil War shows a man who was whipped at Christmas. His back was covered with scars, showing that when masters punished the people they held in bondage, they often did so brutally.

There were other cruel forms of punishment. On one South Carolina plantation, a master angry at an enslaved woman he suspected of miscarrying her pregnancy on purpose locked her up for the Christmas holiday.

Masters sometimes forced enslaved workers to get drunk even if they did not want to drink, or wrestle with each other on Christmas simply for the amusement of the master’s family.

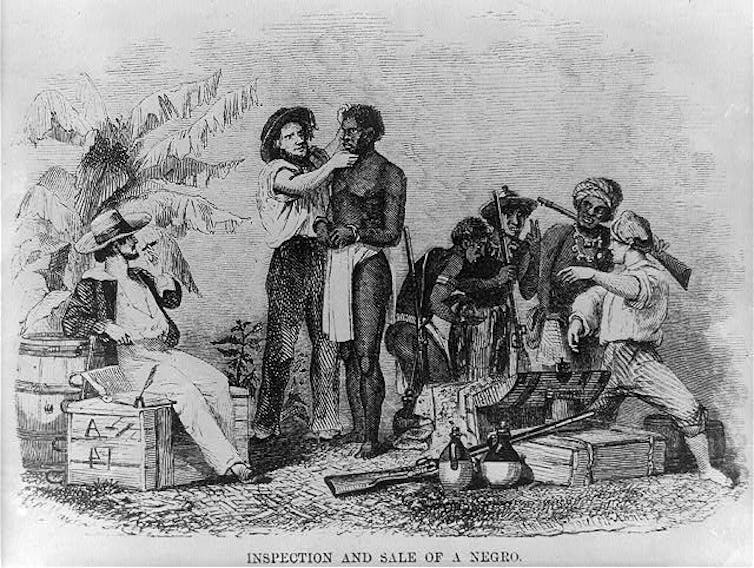

Library of Congress

Likewise, I learned in my research, slaveholders bought and sold plenty of people over the holiday, keeping slave traders busy during Christmas week.

Escapes and panics over slave rebellions

It is revealing that many enslaved black southerners also chose Christmas as the time to try to escape to freedom, despite the difficulties of traveling in cold weather with few supplies.

The famous black liberator Harriet Tubman, for example, helped her three brothers enslaved in Maryland to escape bondage over Christmas in 1854. Obviously, slaves like the Tubman brothers greatly resented their enslavement, or they would not have agreed to leave.

Evidence shows that many slaveholders knew their slaves hated their condition. Although the U.S. never had a major Christmas slave rebellion, southern whites frequently panicked over frequent rumors that their slaves planned to revolt over the holiday. They armed themselves, conducted extra patrols, banned black people from the streets of cities and executed or whipped slaves whose behavior they thought was suspicious.

Panics over Christmas rebellions took place frequently. They were, at times, confined to a state as in Charleston, South Carolina – then a British colony – in 1765. Or, they could spread in the entire American South, as one did in 1856. As I found in my research, Christmas revolt panics continued all the way through the Civil War.

These panics made Christmas a bad time for many slaves, who passed their Christmases in great fear that they would be rounded up and killed.

What’s changing

Some southern historic plantations and mansions are beginning to include a more accurate history of slavery in their presentations of the past.

Montpelier, the Virginia plantation of U.S. president James Madison and Monticello, the famed mansion and plantation of Thomas Jefferson, for example, have been making efforts for several years now to work more accurate presentations.

Yet another onetime slave-owning president’s preserved site, James Monroe’s Highland, likewise is striving to provide a far more comprehensive look at the enslaved people who once lived there and the conditions they experienced.

There are signs that such changes are taking place elsewhere too. In 2013, for example, the Ben Lomond plantation in Virginia featured in its holiday programming the tale of how enslaved people murdered the place’s owner over Christmas. That same year, Montpelier, once home to President James Madison, asked its interpretors at Christmas to explain to visitors that whites living nearby were afraid of violence by Madison’s slaves.

Christmas programming, however, is changing more slowly than programming at other times of the year. That is because many would like the holiday event to be a fun one.

But a public acknowledgment that slavery was immoral, horrific and resisted by its victims in the form of more sensitive and informative Christmas events at historic mansions and plantations might just be a step toward racial reconciliation in the U.S.

Robert E. May, Professor Emeritus of History, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.