African Americans celebrate Watch Night.

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Don’t see the audio player? Click here.

(more…)

Podcast: Embed

Subscribe: RSS

Prisoners pray before getting baptized inside an evangelical cellblock at the Penal Unit N11 penitentiary in Pinero, Santa Fe Province, Argentina, Saturday, Dec. 11, 2021. Prisoners who want to be allowed in an evangelical cellblock must comply with rules of conduct, including praying three times a day, giving up all addictions and fighting. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

ROSARIO, Argentina (AP) — The loud noise from the opening of an iron door marks Jorge Anguilante’s exit from the Pinero prison every Saturday. He heads home for 24 hours to minister at a small evangelical church he started in a garage in Argentina’s most violent city.

Before he walks through the door, guards remove handcuffs from “Tachuela” — Spanish for “Tack,” as he was known in the criminal world. In silence, they stare at the hit-man-turned-pastor who greets them with a single word: “Blessings.”

The burly, 6-foot-1 (1.85-meter) man whose tattoos are remnants of another time in his life — back when he says he used to kill — must return by 8 a.m. to a prison cellblock known by inmates as “the church.”

His story, of a convicted murderer embracing an evangelical faith behind bars, is common in the lockups of Argentina’s Santa Fe province and its capital city of Rosario. Many here began peddling drugs as teenagers and got stuck in a spiral of violence that led some to their graves and others to overcrowded prisons divided between two forces: drug lords and preachers.

Over the past 20 years, Argentine prison authorities have encouraged, to one extent or another, the creation of units effectively run by evangelical inmates — sometimes granting them a few extra special privileges, such as more time in fresh air.

The cellblocks are much like those in the rest of the prison — clean and painted in pastel colors, light blue or green. They have kitchens, televisions and audio equipment — here used for prayer services.

But they are safer and calmer than the regular units.

Violating rules against fighting, smoking, using alcohol or drugs can get an inmate kicked back into the normal prison.

“We bring peace to the prisons. There was never a riot inside the evangelical cellblocks. And that is better for the authorities,” said the Rev. David Sensini of Rosario’s Redil de Cristo church.

Access is controlled both by prison officials and by cellblock leaders who function much like pastors — and who are wary of attempts by gangs to infiltrate.

“It has happened many times that an inmate asks to go to the evangelical pavilion to try to take it over. We need to keep permanent control over who enters”, said Eric Gallardo, one of the leaders at the Pinero prison.

___

Jeremias Echague shows his tattoo from inside his cell within the evangelical cellblock he joined at the Correctional Institute Model U.1., Dr. Cesar R Tabares, known as Penal Unit 1 in Coronda, Santa Fe province, Argentina, where the 19-year-old waits for his final sentencing for homicide, Friday, Nov. 19, 2021. Many here began peddling drugs as teenagers and got stuck in a spiral of violence that led some to their graves and others to overcrowded prisons divided between two forces: drug lords and preachers. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Rosario is best known as a major agricultural port, the birthplace of revolutionary leader Ernesto “Che” Guevara and a talent factory for soccer players, including Lionel Messi. But the city of some 1.3 million people also has high levels of poverty and crime. Violence between gangs who seek to control turf and drug markets has helped fill its prisons.

“Eighty percent of the crimes in Rosario are carried out by young hit men who provide services to drug gangs, whose bosses are imprisoned and maintain control of the criminal business from jails,” said Matías Edery, a prosecutor in the Organized Crime Unit in Santa Fe province.

Anguillante says that his life as a contract killer is behind him; God’s word, he says, turned him into “a new man.”

In 2014, he was sentenced to 12 years in prison for killing 24-year-old Jesús Trigo, whom he shot in the face. Anguillante says that face haunts him at night, and he tries to chase the memory away by praying in his small prison cell.

___

Jeremias Echague shows his tattoo from inside his cell within the evangelical cellblock he joined at the Correctional Institute Model U.1., Dr. Cesar R Tabares, known as Penal Unit 1 in Coronda, Santa Fe province, Argentina, where the 19-year-old waits for his final sentencing for homicide, Friday, Nov. 19, 2021. Many here began peddling drugs as teenagers and got stuck in a spiral of violence that led some to their graves and others to overcrowded prisons divided between two forces: drug lords and preachers. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

About 40% of Santa Fe province’s roughly 6,900 inmates live in evangelical cellblocks, said Walter Gálvez, Santa Fe’s undersecretary of penitentiary affairs, who is also Pentecostal.

As in other Latin American countries, the spread of evangelical faith in Argentina took root especially in the “most vulnerable sectors, including inmates,” said Verónica Giménez, a researcher at the National Council for Scientific and Technical Research of Argentina.

In Pope Francis’ home country, the Roman Catholic Church is still the dominant religion. But a survey by the council found that the percentage of Argentine Catholics fell from 76.5% to 62.9% between 2008 and 2019 while the share of evangelicals grew from 9% to 15.3%.

“This increase in the faithful took place even more in prisons,” Gálvez said.

Gimenez, the researcher, said that is echoed in other parts of Latin America, such as in Brazil, where the huge Universal Church of the Kingdom of God has 14.000 people working with prisoners.

The growth is remarkable in a country where Catholics had a near-monopoly on prison chapels until a few decades ago.

“There are still Catholic chapels inside prisons but their priests are almost without any work to do,” said Leonardo Andre, head of the prison in Coronda, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) north of Rosario.

Catholic priest Fabian Belay, who runs the Pastoral of Drug Dependence, said that priests are indeed active, but use “different methods” than the cellblock strategy.

“We disagree with the invention of religious cellblocks because they create ghettos inside prisons,” he said. “We bet on integration and not a religious segregation.”

Deacon Raul Valenti, who has been working in the Catholic pastoral for three decades, said, “The evangelicals do their work in the religious cellblocks, while we do them in the other ones, the ones that are called hell.”

He insisted they are not in conflict: “We just have different views. We share, a lot of times, religious activities inside the prison.”

___

Ruben Munoz, an evangelical pastor from the church Puerta del Cielo, or “Heaven’s Door,” who served two years in prison for robbery, baptizes an inmate in a kiddie pool, at an evangelical cellblock inside Penal Unit N11 in Pinero, Santa Fe province, Argentina, Saturday, Dec. 11, 2021. Over the past 20 years, Argentine prison authorities have encouraged the creation of units effectively run by evangelical inmates. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

The Puerta del Cielo (“Heaven’s Door”) and Redil de Cristo (“Christ’s Sheepfold”) congregations are among those that exert strong influence in Santa Fe’s prisons. They began to evangelize inmates in the late 1980s and today have more than 120 pastors working inside prisons.

During a recent service at the Redil de Cristo church in Rosario, the Rev. David Sensini asked those who had been imprisoned to identify themselves. About a third in the room raised their hands. They then closed their eyes and lowered their head in prayer.

Víctor Pereyra, who was wearing a black suit and tie, served time at the Pinero prison. Today, he owns a produce shop and also works maintenance jobs.

“I don’t want to go back (to prison). Today I have a family to look after,” he said.

Pop-style hymns blared from loudspeakers while three TV cameras recorded the ceremony for other worshippers watching at home via a YouTube channel.

“No one else is going to jail. Not your children, not your grandchildren,” the pastor shouted to the crowd. “Change is possible!”

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

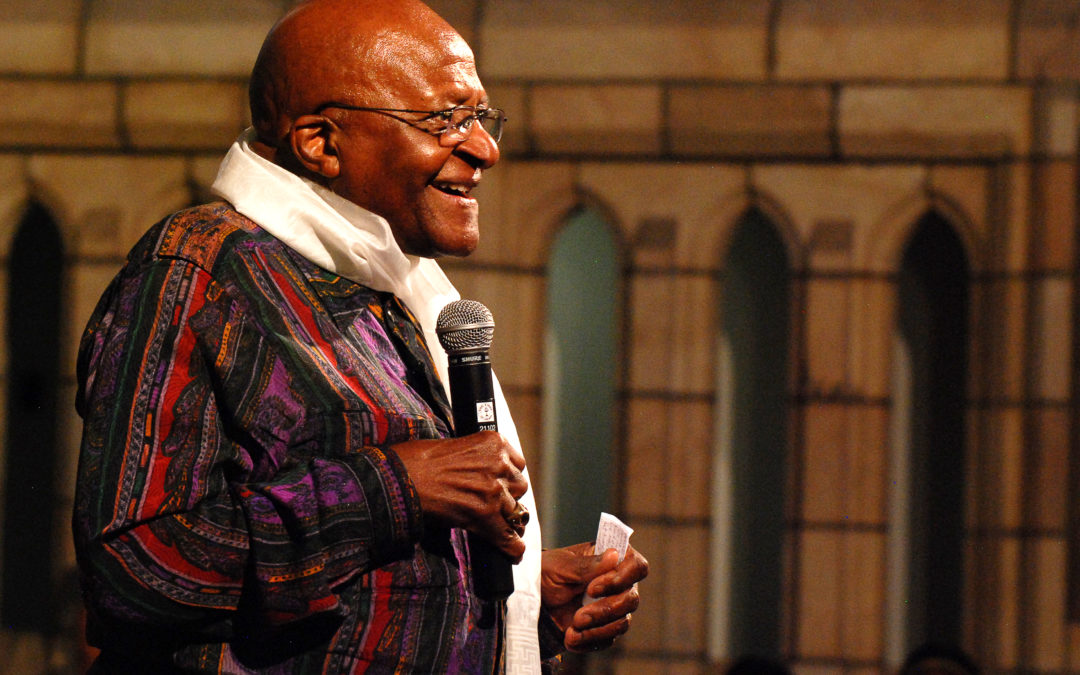

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Mpilo Tutu has died at the age of 90.

Archbishop Tutu earned the respect and love of millions of South Africans and the world. He carved out a permanent place in their hearts and minds, becoming known affectionately as “The Arch”.

When South Africans woke up on the morning of 7 April, 2017 to protest against then President Jacob Zuma’s removal of the respected Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, Archbishop Tutu left his Hermanus retirement home to join the protests. He was 86 years old at the time, and his health was frail. But protest was in his blood. In his view, no government was legitimate unless it represented all its people well.

There was still that sharpness in his words when he said that

We will pray for the downfall of a government that misrepresents us.

These words echoed his stance of ethical and moral integrity as well as human dignity. It is on these principles that he had fought valiantly against the system of apartheid and became, as the Desmond Tutu Foundation rightly affirms,

an outspoken defender of human rights and campaigner for the oppressed.

But Archbishop Tutu didn’t stop his fight for human rights once apartheid came to a formal end in 1994. He continued to speak critically against politicians who abused their power. He also added his weight to various causes, including HIV/AIDS, poverty, racism, homophobia and transphobia.

His fight for human rights wasn’t limited to South Africa. Through his peace foundation, which he formed in 2015, he extended his vision for a peaceful world “in which everyone values human dignity and our interconnectedness”.

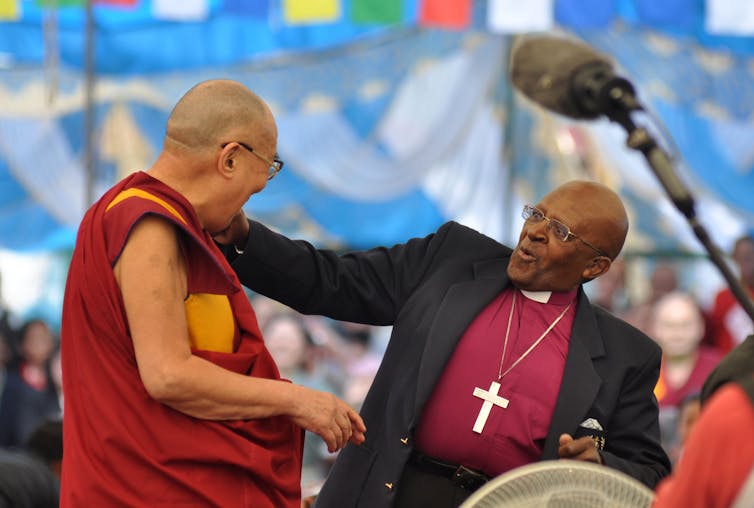

He also became relentless in his support for the Dalai Lama, whom he considered his best friend. He condemned the South African government for refusing the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader a visa to deliver the “Desmond Tutu International Peace Lecture” in 2011.

Archbishop Tutu came from humble beginnings. Born on 7 October, 1931 in Klerksdorp, in the North West Province of South Africa where his father, Zachariah was a headmaster of a high school. His mother, Aletha Matlare, was a domestic worker.

One of the most influential figures in his early years was Father Trevor Huddleston, a fierce campaigner against apartheid. Their friendship led to the young Tutu being introduced into the Anglican Church.

After completing his education he had a brief stint teaching English and History at Madibane High School in Soweto; and then at Krugersdorp High School , west of Johannesburg; where his father was a headmaster. It was here that he met his future wife, Nomalizo Leah Shenxane.

It is interesting that he agreed to a Roman Catholic wedding ceremony, although he was Anglican. This ecumenical act at the very early stage in his life gives us a hint of his commitment to ecumenical work in later years.

He quit teaching in the wake of the introduction of the inferior “Bantu education” for black people in 1953. Under the Bantu Education Act, 1953, the education of the native African population was limited to producing an unskilled work force.

In 1955 Tutu entered the service of the church as a sub-deacon. He got married the same year. He enrolled for theological education in 1958 and, after completing his studies, was ordained as a deacon of Saint Mary’s Cathedral in Johannesburg in 1960, and became its first black dean in 1975.

In 1962 he went to London to pursue further theological education with funding from the World Council of Churches. He earned a Master of Theology degree, and after serving in various parishes in London, returned to South Africa in 1966 to teach at the Federal Theological Seminary at Alice, Eastern Cape.

One of the lesser known facts is that he had special interest in the study of Islam. He had wanted to pursue this in his doctoral studies, but this was not to be.

The activities he was involved in in the early 1970s were to lay the foundation for his political struggle against apartheid. These included teaching in Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland and, thereafter, a posting to London as the Associate Director for Africa at the Theological Education Fund, and his exposure to Black Theology. He also visited many African countries in the early 1970s.

He eventually returned to Johannesburg as the dean of Johannesburg and the rector of St. Mary’s Anglican Parish in 1976.

It was at St Mary’s that Tutu first confronted the then apartheid Prime Minister John Vorster, writing him a letter in 1976 decrying the deplorable state in which black people had to live.

On 16 June Soweto went up in flames, when black high school pupils protested against the forced use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction, and were mowed down by apartheid police.

Bishop Tutu was thrust deeper and deeper into the struggle. He delivered one of his most passionate and fiery orations following the death in detention of the black consciousness leader, Steve Biko in 1977.

His role as the General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches, and later as the rector of St. Augustine’s Church in Orlando West in Soweto, saw him become an ardent critic of the most egregious aspects of apartheid. This included the forced removals of black people from urban areas deemed to be white areas.

With his growing political activism in the 1980s, the Arch became a target of the apartheid government’s full scale victimisation and faced death threats as well as bomb scares. In March 1980 his passport was revoked. After much international outcry and intervention, he was given a “limited travel document” two years later to travel overseas.

His work was recognised globally, and he was awarded Nobel Prize for Peace in 1984 for being a unifying leader in the campaign to resolve the problem of apartheid in South Africa.

He went on to receive more distinguished awards. He became the Bishop of Johannesburg in 1984, and the Archbishop of Cape Town in 1986. In the following four years leading up to the release of Nelson Mandela after 27 years in prison, the Arch had his work cut out for him. This involved campaigning for international pressure to be brought on the apartheid through sanctions.

After 1994, he headed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Its primary goal was to afford those who committed human rights abuses – for or against apartheid – the opportunity to come clean, offer legal amnesty to deserving ones, and to enable the perpetrators to make amends to their victims.

Two greatest moments in his personal life took his theological outlook beyond the confines of the Church. One was when his daughter Mpho declared she was gay and the church refused her same sex marriage. The Arch proclaimed

If God, as they say, is homophobic, I wouldn’t worship that God.

The second was when he declared his preference for assisted death.

South Africa is blessed to have had such a brave and courageous man as The Arch, who truly symbolised the idea of the country as a “rainbow nation” . South Africa will feel the loss of the moral direction of this brave soldier of God for generations to come. Hamba kahle (go well) Arch.![]()

P. Pratap Kumar, Emeritus Professor, School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics, University of KwaZulu-Natal

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

David E. Talbert, Director of Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey, has written and directed a delightful musical with more black and brown faces than you typically see in a movie of its type. Talbert’s son inspired him to write the film after they started to watch one of his childhood favorites, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Let’s just say his son wasn’t feeling it.

“My son is looking at me like, what is wrong with this dude? And he asked if he could get up and play with his Legos? I said you don’t like the movie? He says, ‘mmmm.’ And as he walked away, I looked at him, and I looked at that screen. I’m like, oh, on his wall, he has Miles Morales and Black Panther. And that’s when it occurred to me. He didn’t do it because he didn’t see anybody that looked like him on that screen,” said Talbert.

That’s when Talbert approached Netflix about what happened with his son and the fact that there aren’t any holiday musical options with a majority of people of color. Scott Stuber, the head of original films at Netflix, agreed with him and decided they had to do something about it. So they did.

Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey follows legendary toymaker Jeronicus Jangle (Academy Award winner Forest Whitaker) whose fanciful inventions burst with whimsy and wonder. But when his trusted apprentice (Emmy winner Keegan-Michael Key) steals his most prized creation, it’s up to his equally bright and inventive granddaughter (newcomer Madalen Mills) — and a long-forgotten invention — to heal old wounds and reawaken the magic within.

Urban Faith talked with Talbert about his movie, its nods to the Black church, and advice he’d give to aspiring filmmakers of color.

David E. Talbert, Director of Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey, on Magic Man G and the influence of African American culture and music.

It’s impressive that Netflix was so receptive to your Christmas movie vision as I’ve heard that Black filmmakers struggle with getting blockbuster-type movies made.

Well, we do, but you know, before Black Lives Matter, and the racial and political unrest, and the pandemic, there was a wave and a Renaissance that was happening. And you know, from Get Out that Jordan Peele did — you know, Black people never lived past five minutes in a horror movie. They paid us by the minute. But Jordan Peele broke the mold with that. And then Ryan Kyle Coogler with Black Panther. You can’t watch a Marvel movie unless you see, God rest his soul, Chadwick Boseman, his character, or the general or the little sister, you’ve gotta see them in those worlds now. And so those films normalized people, representation, and genres. And that’s what this film is doing, too. It’s normalizing people of color in worlds of wonder. And I think this Renaissance is happening, and Netflix knew that they were ahead of the curve. They knew that we not only wanted it as a Black community, but the world wants it, too. We’re number one in 23 countries worldwide, and we’re in the top 10 films in 70 countries around the world.

You’ve spoken about the nods to the Black Church in your movie. Did you grow up in the Black Church?

My great grandmother was one of the founding pastors of the Pentecostal movement in DC. — Pastor Annie Mae Woods. I grew up in a storefront church, three generations of holiness preachers I was raised under. And you know, I watched the Word of God change people’s lives. And just words moved people to tears, to reconciliation, to reform. In addition to that, there’s no better theater than the Black church. I mean, watching the sisters shout and then somebody tried to touch their purse, and they stopped mid-shout to get their purse. But it was a community full of heart and warmth and love and messaging, and meaning that moved me as a kid and stays with me as an adult.

How did those experiences shape you as a director?

Well, you write what you know. You write stories and pieces of stories you’re inspired by, that you grew up with. I mean, Jeronicus Jangle is the journey of Job. He had everything, lost everything, and he got everything back. He lost his faith, he lost his belief, he questioned God, he questioned himself, he’s like all of that. But it was a path, it was his journey to get back to what he had, and even more so. I’m not a religious person at all. I’m a proud member of bedside Baptist. But I’m spiritual. I’m not about religion; I’m about relationship more. But these things are in me. These are my part of my DNA. And so, I never do my art to preach to anybody, but the themes or lessons of morality will always be in there because that’s who I am.

Share more about the symbolism of Black culture and the Black Church in the movie.

The background dancers were the Pips in the Temptations, and the Four Tops and the Dramatics, and all those groups are grown men dancing and choreographed movement that we love. And with “Magic Man G,” that’s the Black church. I mean the shout music in there. It was like New Orleans. But that’s shout music up in Magic Man G. And then the emotion of this day and a spirit. And, you know, all of that is entrenched in African American music, soul music, music from the continent. In the snowball scene, that’s an artist from Ghana, Bisa Kdei. So, we just want to celebrate our music that we love, but that’s universal. The world loves our music. And so, I wasn’t shy about doing what moves me—and growing up in a Black church, this is the music that moved me.

What advice would you give for future filmmakers of color?

That all is possible, and don’t put yourself in a box. Don’t let anybody else put you in a box. You know, my grandmother told the story of what they did when she was growing up. She said that they took grasshoppers that used to jump six feet high into the air and put them in an old jelly jar. They would poke holes in the jelly jar and put a grasshopper in there. When they took the grasshopper out the next day, the grasshopper only jumped six inches because that’s all the room they had. The grasshopper then who could jump to the sky had been taught that he could only jump this high. And she told me that to say never forget how high you were created to soar. As artists and inventors and innovators, we can soar to the sky. Don’t let people put you in that jelly jar, poke holes in it, and then teach you that you can only soar six inches.

When Ashlee Wisdom launched an early version of her health and wellness website, more than 34,000 users — most of them Black — visited the platform in the first two weeks.

“It wasn’t the most fully functioning platform,” recalled Wisdom, 31. “It was not sexy.”

But the launch was successful. Now, more than a year later, Wisdom’s company, Health in Her Hue, connects Black women and other women of color to culturally sensitive doctors, doulas, nurses and therapists nationally.

As more patients seek culturally competent care — the acknowledgment of a patient’s heritage, beliefs and values during treatment — a new wave of Black tech founders like Wisdom want to help. In the same way Uber Eats and Grubhub revolutionized food delivery, Black tech health startups across the United States want to change how people exercise, how they eat and how they communicate with doctors.

Inspired by their own experiences, plus those of their parents and grandparents, Black entrepreneurs are launching startups that aim to close the cultural gap in health care with technology — and create profitable businesses at the same time.

“One of the most exciting growth opportunities across health innovation is to back underrepresented founders building health companies focusing on underserved markets,” said Unity Stoakes, president and co-founder of StartUp Health, a company headquartered in San Francisco that has invested in a number of health companies led by people of color. He said those leaders have “an essential and powerful understanding of how to solve some of the biggest challenges in health care.”

Platforms created by Black founders for Black people and communities of color continue to blossom because those entrepreneurs often see problems and solutions others might miss. Without diverse voices, entire categories and products simply would not exist in critical areas like health care, business experts say.

“We’re really speaking to a need,” said Kevin Dedner, 45, founder of the mental health startup Hurdle. “Mission alone is not enough. You have to solve a problem.”

Dedner’s company, headquartered in Washington, D.C., pairs patients with therapists who “honor culture instead of ignoring it,” he said. He started the company three years ago, but more people turned to Hurdle after the killing of George Floyd.

In Memphis, Tennessee, Erica Plybeah, 33, is focused on providing transportation. Her company, MedHaul, works with providers and patients to secure low-cost rides to get people to and from their medical appointments. Caregivers, patients or providers fill out a form on MedHaul’s website, then Plybeah’s team helps them schedule a ride.

While MedHaul is for everyone, Plybeah knows people of color, anyone with a low income and residents of rural areas are more likely to face transportation hurdles. She founded the company in 2017 after years of watching her mother take care of her grandmother, who had lost two limbs to Type 2 diabetes. They lived in the Mississippi Delta, where transportation options were scarce.

“For years, my family struggled with our transportation because my mom was her primary transporter,” Plybeah said. “Trying to schedule all of her doctor’s appointments around her work schedule was just a nightmare.”

Plybeah’s company recently received funding from Citi, the banking giant.

“I’m more than proud of her,” said Plybeah’s mother, Annie Steele. “Every step amazes me. What she is doing is going to help people for many years to come.”

Health in Her Hue launched in 2018 with just six doctors on the roster. Two years later, users can download the app at no cost and then scroll through roughly 1,000 providers.

“People are constantly talking about Black women’s poor health outcomes, and that’s where the conversation stops,” said Wisdom, who lives in New York City. “I didn’t see anyone building anything to empower us.”

As her business continues to grow, Wisdom draws inspiration from friends such as Nathan Pelzer, 37, another Black tech founder, who has launched a company in Chicago. Clinify Health works with community health centers and independent clinics in underserved communities. The company analyzes medical and social data to help doctors identify their most at-risk patients and those they haven’t seen in awhile. By focusing on getting those patients preventive care, the medical providers can help them improve their health and avoid trips to the emergency room.

“You can think of Clinify Health as a company that supports triage outside of the emergency room,” Pelzer said.

Pelzer said he started the company by printing out online slideshows he’d made and throwing them in the trunk of his car. “I was driving around the South Side of Chicago, knocking on doors, saying, ‘Hey, this is my idea,’” he said.

Wisdom got her app idea from being so stressed while working a job during grad school that she broke out in hives.

“It was really bad,” Wisdom recalled. “My hand would just swell up, and I couldn’t figure out what it was.”

The breakouts also baffled her allergist, a white woman, who told Wisdom to take two Allegra every day to manage the discomfort. “I remember thinking if she was a Black woman, I might have shared a bit more about what was going on in my life,” Wisdom said.

The moment inspired her to build an online community. Her idea started off small. She found health content in academic journals, searched for eye-catching photos that would complement the text and then posted the information on Instagram.

Things took off from there. This fall, Health in Her Hue launched “care squads” for users who want to discuss their health with doctors or with other women interested in the same topics.

“The last thing you want to do when you go into the doctor’s office is feel like you have to put on an armor and feel like you have to fight the person or, like, you know, be at odds with the person who’s supposed to be helping you on your health journey,” Wisdom said. “And that’s oftentimes the position that Black people, and largely also Black women, are having to deal with as they’re navigating health care. And it just should not be the case.”

As Black tech founders, Wisdom, Dedner, Pelzer and Plybeah look for ways to support one another by trading advice, chatting about funding and looking for ways to come together. Pelzer and Wisdom met a few years ago as participants in a competition sponsored by Johnson & Johnson. They reconnected at a different event for Black founders of technology companies and decided to help each other.

“We’re each other’s therapists,” Pelzer said. “It can get lonely out here as a Black founder.”

In the future, Plybeah wants to offer transportation services and additional assistance to people caring for aging family members. She also hopes to expand the service to include dropping off customers for grocery and pharmacy runs, workouts at gyms and other basic errands.

Pelzer wants Clinify Health to make tracking health care more fun — possibly with incentives to keep users engaged. He is developing plans and wants to tap into the same competitive energy that fitness companies do.

Wisdom wants to support physicians who seek to improve their relationships with patients of color. The company plans to build a library of resources that professionals could use as a guide.

“We’re not the first people to try to solve these problems,” Dedner said. Yet he and the other three feel the pressure to succeed for more than just themselves and those who came before them.

“I feel like, if I fail, that’s potentially going to shut the door for other Black women who are trying to build in this space,” Wisdom said. “But I try not to think about that too much.”

Subscribe to KHN's free Morning Briefing.