by Stefanie A. Bohde | Jun 6, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

COMMUNITY SERVICE: Elevate Detroit staff members and volunteers serve area residents during one its CommuniD Barbecues last year at Detroit’s Robert Redmond Memorial Park.

Is Detroit coming or going?

The conventional wisdom is that the once-bustling Motor City is the epitome of a metropolis in decline, a remnant of a bygone industrial era. But for many of us who have decided to intentionally make Detroit our home, we choose to believe that the city has a future.

It’s in our nature, I guess. We love to root for the underdog, and Detroit is definitely that. As politicians, businesspeople, and sociologists ponder the city’s chances, it takes faith to see a bright future for a city that has lost so much of its luster. But over the last few years, the city’s been gaining notoriety as a business incubator (see Detroit’s Future: From Blight to Bright), a destination for good eats, and the slow (but steady) revival of America’s number one auto manufacturing center. It’s home to four professional sports teams, including the Lions who went from serving as the laughingstock of the National Football league to finishing with a 10-6 season and making their first playoff appearance since 1999. Most recently, Detroit was even rated as having one of America’s top ten best downtowns. Detroit’s full of previously unrecognized promise. It’s resilient, tenacious, and on the verge of exciting change.

VITAL SIGNS: An attractive waterfront, competitive sports teams, and fine restaurants give Detroiters reason for hope.

However, a lot is still broken. Detroit’s also been synonymous with present-day notions of urban crime, decay, and impoverishment. At the height of its powers in 1950, Detroit had 1.8 million residents and a thriving economy that helped drive the fortunes of the rest of the nation. Now, 60 years later, the population has dropped to just 700,000 and is in a desperate struggle to recapture its cultural and economical relevance.

Over the past few years, Detroit has become a case study in what ails American cities. In 2010, Time magazine set up a special outpost in the city for a year to chronicle the city’s challenges. And a new book, Detroit: A Biography, finds former Detroit News reporter Scott Martelle analyzing what led to the city’s current misfortunes. Though a sobering read, a strength of the book is that it doesn’t live in the past by romanticizing the bygone glories of the auto industry or the Motown era. Instead, Martelle drills deep into the troubling factors that contributed to Detroit’s decline. Endeavors like Time’s reporting project and Martelle’s book are important reminders of Detroit’s challenges and possibilities.

Detroit is a city begging for educational reform and financial restructuring. And though Michigan’s unemployment rate has steadily decreased over the past year, Metro Detroit’s rate remains higher than state and national averages at 9.2% as of April.

Still, we hope.

Let the Sonshine

With unemployment rounding out at over 50,000, Detroiters have begun exploring other employment options. Detroit residents have begun to reimagine how to create a more sustainable economy — one that isn’t dependent upon a single industry. Through the diversification of business endeavors, some see slow progress.

Historically, a bottom-up, micro-level approach to local economic development has proven to be the most effective. According to the World Bank in a recent report, “Local economic development is about local people working together to achieve sustainable economic growth that brings economic benefits and quality of life improvements for all in the community.”

THE ROAD AHEAD: Downtown Detroit as seen along Woodward Avenue. Strapped with the fallout of crime, poverty, and political corruption, city leaders are in a desperate search for answers. Meanwhile, a cadre of Christian visionaries hope to become part of the solution. (Photo: Rebecca Cook/Newscom)

Some Detroit entrepreneurs have even begun to use their business ventures in order to combat joblessness in their individual communities. Take, for example, Café Sonshine, a local eatery in the New Center neighborhood which employs local residents and provides a community gathering space. Or examine Wayne State University’s Tech Town, an organization that trains and equips fledgling local entrepreneurs with the tools they need to foster a successful business.

Following are the stories of three entrepreneurs who are working to address poverty and stimulate the metropolitan Detroit area through local business. Though all significantly different from each other, these individuals share the same passion and enthusiasm to eradicate poverty, share the love of Christ through community, and see Detroit become healthy and whole.

Community Elevation

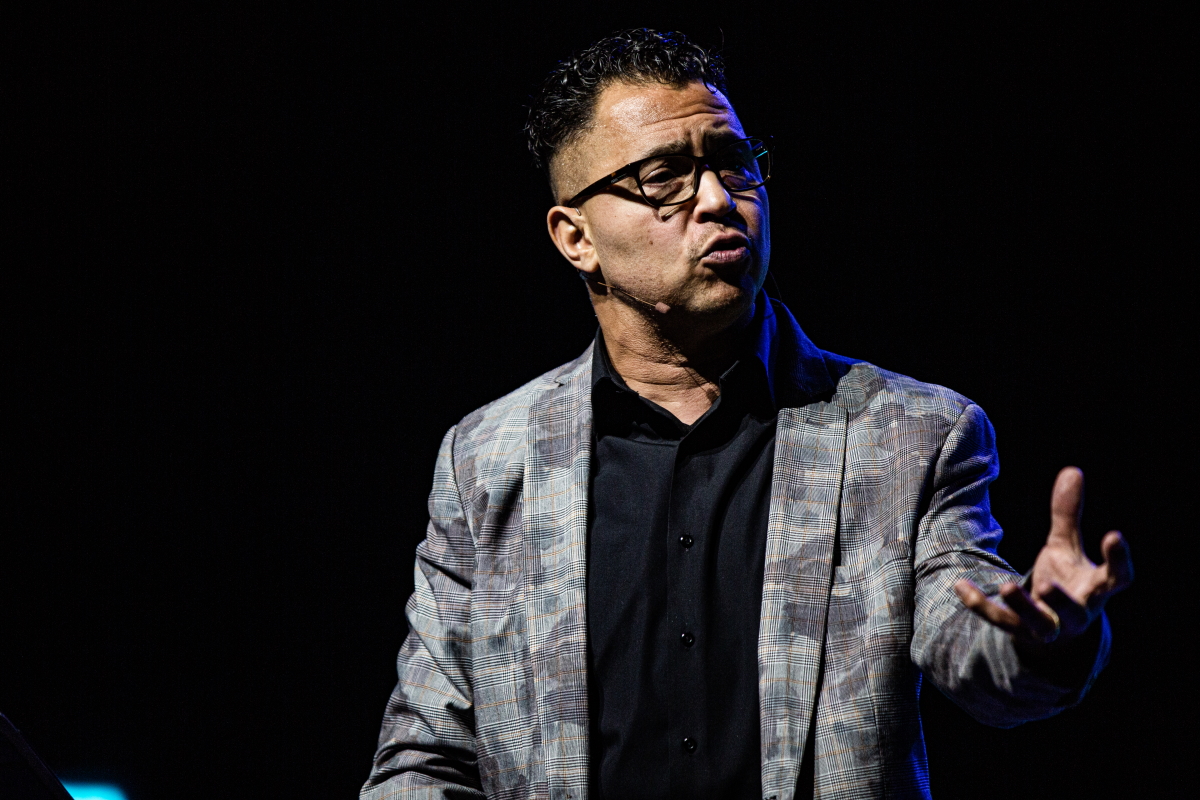

GO-GETTER: Elevate Detroit’s Mike Schmitt

Mike Schmitt, director and community architect at Elevate Detroit, has a very intentional vision for his corner of Detroit. He’s firmly planted himself in the geographical area called Cass Corridor. The neighborhood — a small grid of streets located in the Midtown district — has been coined by some as “the Jungle.” It’s a high crime area rife with prostitution, drug dealing, and a strong gang presence that dates back to the early twentieth century. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre was even partially plotted in Cass Corridor by Detroit’s Purple Gang, associates of Al Capone.

“It’s entirely likely that the same people who may have smiled at you earlier in the day have been up all night making drug runs, selling crack and heroin,” said Schmitt. “Though there are more churches per capita in Detroit than in any other city, there’s an unfed hunger here for community and love.”

Four years ago, Schmitt started Elevate Detroit and a related outreach event called CommuniD BBQs. To date, Elevate Detroit now organizes five BBQs in four different cities — Detroit, Flint, Pontiac, and Mount Clemens. Each week, people come from across the metro Detroit area to join in fellowship with people of different ethnicities and socio-economic positions. On these Saturdays, it’s a piece of God’s kingdom here on earth.

“I’ve tried to move away a couple of times now, but Detroit is my home. Once you see God moving in so many different ways, it’s impossible to leave,” he said.

SERVING THE WHOLE PERSON: Community residents wait in line for food and other resources during Elevate Detroit’s CommuniD Barbecue and mobile health clinic events.

Schmitt also is the primary visionary behind Dandelion’s Café, a new business and community outreach model in the heart of Cass Corridor. Though not officially off the ground yet, Schmitt and his team are in the process of raising capital and hope to get started soon. The hope is for Dandelion’s Café to serve the dual purpose of a coffee shop and concert venue in the building directly adjacent to the park at 2nd and Seldon in Detroit. Schmitt dreams of hosting open-mic nights, karaoke nights, local music nights, and even bring in national acts for concerts. Schmitt and his crew envision this venue becoming a center for community in the neighborhood and creating jobs for those who are in disadvantaged situations.

To complement this model, Schmitt hopes to purchase a nearby house or small apartment building for his previously homeless employees to live in with other residents — families, singles, and the elderly alike. He sees this partially as an antidote to the “No ID” problem. Without a permanent residence to reference on employment applications, it’s impossible for many transients to nail down a job. And without a source of income, the cycle of poverty repeats itself.

“I believe that by doing life together, we’ll create a support network for those who don’t have one,” said Schmitt. “The more that I came down to Detroit from my suburban home, the more I started to realize how much we all had in common and I wanted to do something to help cultivate a support network for those who didn’t have one.”

Harriet Tubman in Detroit

Similarly, Mark Wholihan of The Car Whisperers, LLC yearns for Detroit’s “second chance.” Wholihan began praying for a purpose from God immediately after he became a Christian. After praying for more than eight hours straight one day, he began to envision a new kind of auto repair service, an opportunity that would allow him to use his business to employ people in his community with a lack of resources.

VEHICLE FOR OUTREACH: In this ad for his auto shop, Mark Wholihan stands out in his red suit. He launched the business as a way to connect with people in his Detroit community while aiding the city’s restoration.

The Car Whisperers, LLC opened in February of last year in Livonia, Michigan. This mobile mechanic auto repair facility services western Wayne County. Because it’s largely connected to other cities through an infrastructure of highways, the city of Livonia is an ideal base of operations for any largely mobile organization. Additionally, with easy access to cities such as Farmington Hills, Detroit, Canton, and Allen Park, its socioeconomic range of customers is widely varied and diverse.

“When God put this business on my heart, I nicknamed it The Harriet Tubman Mission,” said Wholian. “Through using this business, I’m trusting God to help me bring people from slavery to freedom.”

Like Mike Schmitt, Wholihan envisions his auto repair service as a stepping stone to a larger organization designed to provide clients with total rehabilitation. In the case of The Car Whisperers, he has dreams of founding a residential long-term rehabilitation program in Detroit for people in need of holistic recovery. This projected program, called Second Chance at Life, will include a homeless shelter, drug and alcohol rehabilitation program, job placement services and an education center. As they continue to develop the micro-economy that will help to fund such an endeavor, Wholihan and The Car Whisperers are partnering with the YWCA community centers in order to expand how they meet the needs of their community.

“Reducing drug and alcohol abuse, unemployment, homelessness, crime, poverty and the return to previous lifestyles will make the program successful,” declares a blurb on the ministry’s website. “[It is our hope] to help Detroit and the surrounding communities to become a better, safer place for everyone.”

Repairer of Broken Walls

Like the Wholihan and Schmitt, Lisa Johanon and her non-profit ministry, the Central Detroit Christian Community Development Corporation (CDC), are targeting poverty and joblessness in Detroit through a grassroots movement. Johanon lives and works several blocks north of the burgeoning New Center district in Detroit. Located adjacent to the Midtown neighborhood and about three miles north of downtown, New Center was developed in the 1920s as a business hub that could serve as a connecting point between downtown resources and outlying factories. Today, New Center is slowly developing into a commercial and residential success. From the summer-long event series in New Center Park to the growing headquarters of the Henry Ford Health System, New Center is making its mark on the Greater Detroit area.

FRESH VISION: Lisa Johanon (right) and her daughter Emma. (Photo: Cybelle Codish)

But blocks away in the neighborhoods north of New Center where Johanon lives, it’s another story. Though only separated by some city streets and skyscrapers, this area hasn’t been able to grasp the same commercial success that its evolving counterpart has enjoyed. Rooted in a chronic, generational poverty, these residential neighborhoods have more than just economic obstacles to overcome. The community’s struggles with drug abuse and mental illness are visibly prominent. It’s been calculated that up to 72% of the households are single-parent families. Johanon said the amount of tragedy and injustice has led residents to ask God, “Why?”

“You can’t talk about Jesus when your neighbors are hungry and don’t have a job,” said Johanon. “Long term impact happens because someone is walking beside them.”

So, that’s what Johanon made plans to do. She moved to Detroit in 1987 after helping plant a church in Chicago’s notorious Cabrini Green housing projects. During her first seven years in Detroit, Johanon established and oversaw the Urban Outreach division of Detroit Youth for Christ. From there, she went on to become the executive director of the CDC, which she co-founded more than 15 years ago. She’s been planted there ever since.

The CDC aims to be a well-rounded resource for the central Detroit area. They organize and administer educational programs, orchestrate employment training, and create opportunities to spur job growth in the area. With their outreach initiatives and organic structure, the CDC takes Isaiah 58:12 to heart — “Your people will rebuild the ancient ruins and will raise up the age-old foundations; you will be called Repairer of Broken Walls, Restorer of Streets with Dwellings.”

“The CDC is the model for economic development in our community,” said Johanon. “Walmart isn’t going to come to our neighborhood, so we have to create the job opportunities ourselves.”

Of the three Detroiters highlighted, Johanon has the most business experience to date. The CDC has launched five businesses in their community — Peaches & Greens Produce Market, Higher Ground Landscaping, Café Sonshine, CDC Property Management, and Restoration Warehouse. Each business has a twofold goal — to meet the needs of its community members and simultaneously provide them with jobs.

ON THE MOVE: Lisa Johanon (far right) and her Central Detroit Christian Development Corporation team received a May 2010 visit from First Lady Michelle Obama, who was encouraged by CDC’s Peaches & Greens venture, which provides Detroit neighborhoods with access to low-cost fruits and vegetables through a produce truck and store which are clean and safe. Mrs. Obama, whose “Let’s Move!” initiative targets the problem of childhood obesity, hailed the CDC’s efforts.

But it’s not just about providing community members with a sense of dignity that financial stability can bring. Johanon understands that there needs to be a holistic approach to the restoration of dignity – an approach that includes attention to a person’s physical, social, and spiritual needs.

“The CDC believes that education empowers our community to grow and thrive. Employment equips our community to sustain families. [And] economic development transforms our community,” said a source on their website.

It’s easiest to understand what the CDC aims to do by looking at individual stories. “When we hired people from the neighborhood to work for Higher Ground Landscaping, not a single one could pass a drug test. Now, we only have two who still fail,” said Johanon. “The minority has pressure to change their lifestyle. We want to show that we’re committed for the long term.”

And she’s right — it’s consistent commitment that’s going to change the DNA of Detroit. Each of the entrepreneurs featured in this piece have committed their time, experience, and vision to making their little corner of Detroit more sustainable. In essence, they’ve surrendered their lives to God and His mission for them. And this is something that no politician or urban developer will ever be able to replicate — God using ordinary people to bring about change and renewal. Ultimately, Detroit’s revival — and the resurgence of any ailing city — will start and end with these kind of committed efforts.

by Christine A. Scheller | Dec 6, 2011 | Feature |

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book, Black Fire: 100 Years of African American Pentecostalism, the Regent University visiting professor traces those roots back to the Azusa Street Revival and beyond. Alexander was so influenced by what she learned that she’s spearheading the launch of William Seymour College in Washington, D.C., to continue the progressive Pentecostal legacy of one of the movement’s most important founders. Our interview with Alexander has been edited for length and clarity.

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book, Black Fire: 100 Years of African American Pentecostalism, the Regent University visiting professor traces those roots back to the Azusa Street Revival and beyond. Alexander was so influenced by what she learned that she’s spearheading the launch of William Seymour College in Washington, D.C., to continue the progressive Pentecostal legacy of one of the movement’s most important founders. Our interview with Alexander has been edited for length and clarity.

URBAN FAITH: I was introduced to Rev. William Seymour through your book. What was his significance in Pentecostal history and why was it ignored for so long?

ESTRELDA Y. ALEXANDER: I grew up Pentecostal but don’t remember hearing about Seymour until I went to seminary. In my church history class, as they began to talk about the history of Pentecostalism, they mentioned this person who led this major revival, and I’m sitting in class going, “I’ve never heard of him.” I would say part of it was the broad definition of Pentecostalism, which is this emphasis on speaking in tongues, and that wasn’t Seymour’s emphasis. So, even though he’s at the forefront of this revival, he’s out of step with a lot of the people who are around him. Then again, he’s black in a culture that was racist. For him to be the leader would have been problematic, and so he gets overshadowed. I think his demeanor was rather humble, so he gets overshadowed by a lot of more forceful personalities. He doesn’t try to make a name for himself and so no name is made for him. He gets shuffled off to the back of the story for 70 years, then there’s this push to reclaim him with the Civil Rights Movement. As African American scholars start to write, he’s part of the uncovering of the story of early black history in the country.

What was his role specifically in the Azusa Street Revival?

He was the pastor of the church where the revival was held, so these were his people and he stood at the forefront of that congregation. The revival unfolds under his leadership.

The revival initially began with breaking barriers of race, class, and gender, but quickly reverted to societal norms. Why?

Estrelda Alexander

They began as this multi-racial congregation, though I think it still was largely black. Certainly there were people there of every race and from all over the world, and women had prominent roles. That was unheard of in the early twentieth century. They were derided not only for their racial mixing, but also for the fact that women did play prominent roles. But within 10 years, much of that had been erased. As the denominations started to form, which they did within 10 years of the revival, they started to form along racial lines. Sociologist Max Weber talks about the routinizing of charisma, that all new religious movements start with this freedom and openness to new ways of being, but as movements crystallize, they begin to form the customary patterns of other religious movements. You see that happen over and over again. That’s not just Azusa Street; that’s a process that is pretty well documented.

Is there still more racial integration in Pentecostal churches than in the wider of body of churches?

There has been an attempt to recapture the racial openness with certain movements. There’s what we call the Memphis Miracle, an episode where the divided denominations came together and consciously made an effort to tear down some of those barriers. It’s been more or less successful. There’s still quite a bit of division. It’s not on paper. On paper, there’s this idea that we’ve all come together, but the practicality of it doesn’t always get worked out.

Some of the division was about doctrine, in particular in regard to the nature of the Trinity. Was that interconnected with the racial issues, or are those two separate things?

They’re not interconnected. There are certainly some racial overtones in the discussion, but that doctrine gets permeated throughout black and white Pentecostal bodies. One of the interesting things, though, is that one of the longest-running experiments in racial unity was within the Oneness movement, which reformulated the doctrine of the Godhead. The Pentecostal Assemblies of the World has tried very hard to remain inter-racial, and adopted specific steps making sure that when there was elections that the leadership reflected both races. If, for instance, the top person elected was white, then the second person in place would be black. It would go back and forth. It’s now predominantly a black denomination, though.

Does Pentecostal theology make it more hospitable to alternative views of the Trinity?

Oh no. In Pentecostalism there is a major divide over the nature of the Godhead, and so the break over that issue wasn’t hospitable. I was a member of a Oneness denomination for a while, but I’m a theologian, so I’ve come to a more nuanced understanding of the Godhead. But in conversations with others, the language that gets used when they talk about each other’s camps is very strong. They are quick to call each other heretics. Among scholars, we tend to be more accepting of other ways of seeing things, but within the local churches, especially among pastors, that is a real intense issue.

In the book, you say Rev. T.D. Jakes views the Godhead as “manifestations” of three personalities and that he successfully straddles theological fences. How has he been able to do that?

For a lot of the people in the pews, what they see is Jakes’ success, so they don’t even pay attention to or understand that there is a difference. You’ll see people who, if they understood what Jakes was saying, they would not accept it. I’m not saying what Jakes is saying is wrong. I think the Godhead is a mystery and anybody that says they can explain it is not telling the truth.

Continued on page 2.

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book,

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book,