Methodist racial history recalled on 250th anniversary of Asbury’s US arrival

(RNS) — Two and a half centuries ago, Francis Asbury arrived in the United States from Great Britain, bringing with him what would become the Methodist faith. He went on to spread it across the country, with St. George’s Church in Philadelphia as his home base.

St. George’s will mark the occasion of Asbury’s arrival with a weekend of events at the end of October. But the historic church, which remains the oldest continually used Methodist building in the United States, is also the starting point of three African American churches and one denomination after a “walkout” by Black worshippers.

Over time, recounts the Rev. Mark Salvacion, St. George’s current pastor, African Americans —some recently freed from slavery — were segregated to the sides of the church, to the back of the building and to a balcony, preventing them from receiving Communion on the church’s main floor.

Salvacion describes this and other parts of St. George’s history in the church’s “Time Traveler” program for teen confirmation students learning about their faith and in classes of middle-age adults training to become certified lay ministers.

Teenage confirmation students attend a “Time Traveler” program at Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia in 2018. Photo courtesy of HSG

“It’s not just telling happy stories about Francis Asbury itinerating to West Virginia,” said Salvacion, pastor of what is now called Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church. “It’s uncomfortable stories about race and the meaning of race in the United Methodist Church.”

The turning point for many African American worshippers, already dissatisfied with mistreatment, was a Sunday morning in the late 1700s. Lay preacher Richard Allen saw another Black church leader, Absalom Jones, forcibly pulled up while praying on his knees at St. George’s.

That led Allen and some of the other Black attendees to leave what was then known as St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church and strike out on their own — in different ways.

Portraits of Absalom Jones, from left, Harry Hosier and Richard Allen in Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church museum in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of HSG

“This raised a great excitement and inquiry among the citizens, in so much that I believe they were ashamed of their conduct,” wrote Richard Allen in his autobiography. “But my dear Lord was with us, and we were filled with fresh vigour to get a house erected to worship God in.”

In 1791, Allen, who had been a popular preacher at St George’s 5 a.m. service, started what is now Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Asbury dedicated its first building, a former blacksmith shop, in 1794.

“Here’s Asbury and he comes in and he still has this kind of relationship with Richard Allen that is more than just collegial,” the Rev. Mark Tyler, current pastor of Mother Bethel, said of the men who were the first bishops of the Methodist and AME churches, respectively.

“I mean, you go out of your way as the representative and the saint of Methodism in America and you dedicate Mother Bethel. That is a statement that you’re behind this and endorsing it.”

Bronze statue of Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, on the property of Mother Bethel AME Church in Philadelphia on July 6, 2016. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

In 1816, after winning a court battle for its independence from the Methodist Episcopal Church, Allen started the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the nation’s first Black denomination.

Jones went on to serve as a lay leader of the African Church that began in 1792. Two years later, the congregation became affiliated with the Episcopal Church and was renamed the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. Jones was ordained a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802.

Arthur Sudler, director of the Historical Society & Archives at the 1,000-member church, said the 250th anniversary of Asbury’s U.S. arrival is significant not only for the three Philadelphia congregations that began after discord with St. George’s but also for the city and the three denominations they now represent.

“It’s an epochal moment simply because Francis Asbury’s role in helping develop Methodism in America, in part through his participation there at St. George’s, is one of those factors that gave birth to the Black Christian experience in Philadelphia,” he said. “And in America more broadly, because of the seminal role of Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, and Harry Hosier and their connections between what became these three denominations, the AME Church, the United Methodist Church and the Episcopal Church.”

Service at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in 2019. Photo by Dale Williams for D’Zighner Studios

Hosier initially stayed at St. George’s with other Black attenders who did not leave with Jones and Allen. He also was a closer colleague to Asbury than the other two men, having been a traveling companion who preached with the Methodist leader across the South. Allen, a free man, had declined the offer, avoiding a risky return to the region of the country where slavery remained legal.

Hosier helped found another Philadelphia Methodist congregation, which initially met in people’s homes and eventually became known as Mother African Zoar United Methodist Church. Asbury dedicated its building in 1796 and preached there a number of times, according to the United Methodist Church’s General Commission on Archives and History.

After it celebrated its 225th anniversary, Mother Zoar retained its name but merged with New Vision United Methodist Church in north Philadelphia, with a current average of 75 people at in-person worship services. It thus remains the oldest Black congregation in the United Methodist tradition in continuous existence.

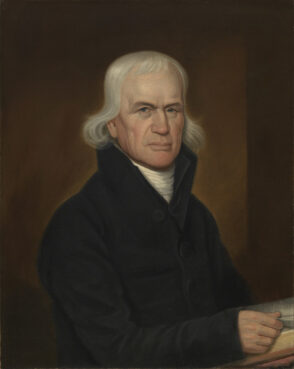

Portrait of Francis Asbury in 1813 by John Paradise. Image courtesy of National Portrait Gallery/Creative Commons

Given the steps of Allen and Jones, why did Hosier and other Black worshippers who once prayed at St. George’s remain within the Methodist Church?

“That is a million-dollar question,” said the Rev. William Brawner, the part-time pastor of Mother Zoar.

He said he assumes “those who left with Absalom, those who left with Richard were tired and figured that they could not change the system of injustice from the inside.” The founders of Zoar chose a different approach, hoping that remaining Methodist would help “change the hearts and minds of the people that were literally oppressing them.”

All these years later, Brawner said he does not judge the different decisions made by African American worshippers at St. George’s, who were unable to freely use spiritual practices that were different from those of white congregants and reflected beliefs some had brought with them from Africa.

“I think people left because of feeling uncomfortable and unaccepted in one place,” he said. “So the split could be celebrated now because of what has become of the split, but people didn’t split out of privilege. People split out of pain. They split because they were hurting.”

The emotions arising from the divisions transcended the centuries.

The Rev. Mark Tyler. Courtesy photo

Tyler, whose church has more than 700 members today, recalled the 2009 service when congregants of Mother Bethel worshipped at St. George’s for what was believed to be the first joint Sunday morning service since the 1700s. As the preacher for that day, he said the gathering was a “cathartic moment,” prompting many of his church’s members to weep.

Salvacion and the clergy of the other churches say occasional joint gatherings have continued since then, such as some of the congregations sharing Easter sunrise services and the annual Episcopal Church observance honoring Absalom Jones.

St. George’s currently has about 15-20 worshippers and a membership of about 50. It expects dozens of United Methodists and invited guests from other churches to attend the Oct. 30-31 commemoration.

Its pastor also expects exchanges and shared events will continue in the future among the congregations whose first members left his church building.

“We all view this history as being common history that we share,” said Salvacion, an Asian man who is one of St. George’s first pastors of color.

Interior of Historic St. George’s United Methodist Church in Philadelphia. Photo courtesy of LOC/Creative Commons

Tyler said the ongoing connections between St. George’s and Mother Bethel probably weren’t envisioned by anyone two centuries ago.

“The current relationship of these two congregations is, in some ways, a sign of hope for what’s possible,” he said. “If it can happen in these two congregations maybe it’s possible for us as a country and as a world. I have to take it for what it is — just a small sign of hope, in spite of all the kind of guarded optimism that I have.”