by Kathryn Post, RNS | Jul 28, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News |

(RNS) — The earliest known depiction of biblical heroines Jael and Deborah was discovered at an ancient synagogue in Israel, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced last week. A rendering of one figure driving a stake through the head of a military general was the initial clue that led the team to identify the figures, according to project director Jodi Magness.

“This is extremely rare,” Magness, an archaeologist and religion professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, told Religion News Service. “I don’t know of any other ancient depictions of these heroines.”

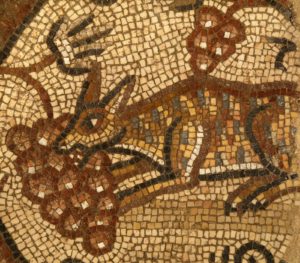

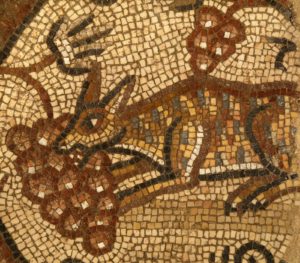

The nearly 1,600-year-old mosaics were uncovered by a team of students and specialists as part of The Huqoq Excavation Project, which resumed its 10th season of excavations this summer at a synagogue in the ancient Jewish village of Huqoq in Lower Galilee. Mosaics were first discovered at the site in 2012, and Magness said the synagogue, which dates to the late fourth or early fifth century, is “unusually large and richly decorated.” In addition to its extensive, relatively well-preserved mosaics, the site is adorned with wall paintings and carved architecture.

The fourth chapter of the Book of Judges tells the story of Deborah, a judge and prophet who conquered the Canaanite army alongside Israelite general Barak. After the victory, the passage says, the Canaanite commander Sisera fled to the tent of Jael, where she drove a tent peg into his temple and killed him.

The newly discovered mosaic panels depicting the heroines are made of local cut stone from Galilee and were found on the floor on the south end of the synagogue’s west aisle. The mosaic is divided into three sections, one with Deborah seated under a palm tree looking at Barak, a second with what appears to be Sisera seated and a third with Jael hammering a peg into a bleeding Sisera.

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic.

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic.

“The value of our discoveries, the value of archaeology, is that it helps fill in the gaps in our information about, in this case, Jews and Judaism in this particular period,” explained Magness. “It shows that there was a very rich and diverse range of views among Jews.”

Magness said rabbinic literature doesn’t include descriptions about figure decoration in synagogues — so the world would never know about these visual embellishments without archaeology.

“Judaism was dynamic through late antiquity. Never was Judaism monolithic,” said Magness. “There’s always been a wide range of Jewish practices, and I think that’s partly what we see.”

These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.

These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.

by Yonat Shimron, RNS | May 20, 2021 | Headline News |

Originally published May 12, 2021

(RNS) — Violence between Gaza and Israel intensified this week to levels not seen for years, with Hamas shooting hundreds of rockets toward the Tel Aviv metropolitan area and Israel retaliating with heavy strikes on Hamas targets in the Gaza Strip.

The buildup to the current conflagration — some are already calling it a new “intifada” or “uprising” — began several weeks ago in a Jerusalem neighborhood near the Old City, close to the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam’s holiest sites for more than 1,200 years.

While Muslims pray at Al-Aqsa year-round, the mosque attracts even more worshippers during Ramadan. Wednesday (May 12) marked the end of Ramadan and the start of Eid al-Fitr, a joyous time for millions of Muslims concluding a monthlong fast.

There’s no doubt that the most extreme Jewish nationalists would like Israel to recapture the Al-Aqsa Mosque because they say it sits on top of the ruins of the ancient Jewish Temple, the only remainder of which is the Western Wall.

But except for the setting of the conflict, faith is only tangentially related to the violence. Here’s a quick explainer on the conflict of the past few days, and what, if any, role religion plays.

Why did Israeli police raid the Al-Aqsa Mosque to begin with?

The Israeli government said the police responded after the Palestinians started throwing stones at them. Palestinians say the fighting really began when police entered the mosque compound on May 10 and started firing rubber-tipped bullets and stun grenades. More than 330 Palestinians were wounded. Israel said 21 of its officers were, too.

But the underlying tensions may have more to do with a set of clashes in the larger east Jerusalem area, which was captured by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War and is home to about 350,000 Palestinians.

For weeks prior to the mosque violence, Palestinians had been protesting the threatened eviction of Palestinian families from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of east Jerusalem. At night they would clash with police and far-right Jewish settlers.

Those clashes are in turn part of a long legal battle over who owns the property. Some Palestinians were relocated to Sheikh Jarrah by the Jordanian government in the 1950s after fleeing their homes during Israel’s War of Independence in 1948.

On May 10, the Israeli Supreme Court was set to decide whether to uphold the eviction of six families from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in favor of Jewish settlers. The court has since postponed the ruling.

So this is a land dispute?

On a large scale, yes. In Sheikh Jarrah, in particular, the dispute originates in the 19th century, when Jews living abroad began returning to what is now Israel and buying properties from Palestinians who lived there. The Jordanians took over the land between 1948 and 1967. Israelis are now claiming it’s theirs again.

The dispute in Sheikh Jarrah takes on political overtones because the neighborhood is part of east Jerusalem, which Palestinians want name as the capital of a future Palestinian state encompassing the West Bank and Gaza. Many Israelis, regardless of their views about a Palestinian state, believe Jerusalem must remain “a Jewish capital for the Jewish people,” and under Israeli control.

What’s Hamas got to do with it?

The clashes between Israel and Palestinians in Jerusalem have united Palestinians far and wide, as have the larger disputes over their displacement and disenfranchisement by Israel. Hamas, the Islamist militant group that controls the Gaza Strip, located about 60 miles south of Jerusalem, sees itself as a defender of Palestinians.

Hamas is at root an Islamic organization born from members of the Muslim Brotherhood, and so it also cares deeply about the Al-Asqa Mosque, which Muslims call the Noble Sanctuary.

On May 12, Israel assassinated several Hamas commanders in retaliation for the barrage of rockets on Tel Aviv, Ashkelon and Israel’s main international airport in the city of Lod.

What role does Judaism or Islam play in this?

At heart, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a dispute over land. But religion is often the proxy for those disputes, pitting two different ethnicities and religions. Little wonder those tensions tend to flare around religious holidays, both Jewish and Muslim.

But Hamas’ main goal is not war with Judaism, but rather with Israel, which is occupying land it believes is inherently Palestinian.

As Hamas has become more emboldened over the years, so too, have Jewish nationalists. On Monday, May 10, which was Jerusalem Day, a national holiday celebrating the unification of Jerusalem, Jewish nationalists marched through the Old City of Jerusalem, including the Muslim Quarter, in a display that provoked and angered many Palestinians.

As often happens, the exclusive claims to parts of the holy city often turn deadly.

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic.

Magness said it’s impossible to know why this rare image was included but noted that additional mosaics depicting events from the Book of Judges, including renderings of Sampson, are on the south end of the synagogue’s east aisle. According to the UNC-Chapel Hill press release, the events surrounding Jael and Deborah might have taken place in the same geographical region as Huqoq, providing at least one possible reason for the mosaic. These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.

These groundbreaking mosaics have been removed from the synagogue for conservation, but Magness hopes to return soon to make additional discoveries. The Huqoq Excavation Project, sponsored by UNC-Chapel Hill, Austin College, Baylor University, Brigham Young University and the University of Toronto, paused in 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic and is scheduled to resume next summer.