by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Feb 19, 2020 | Heritage |

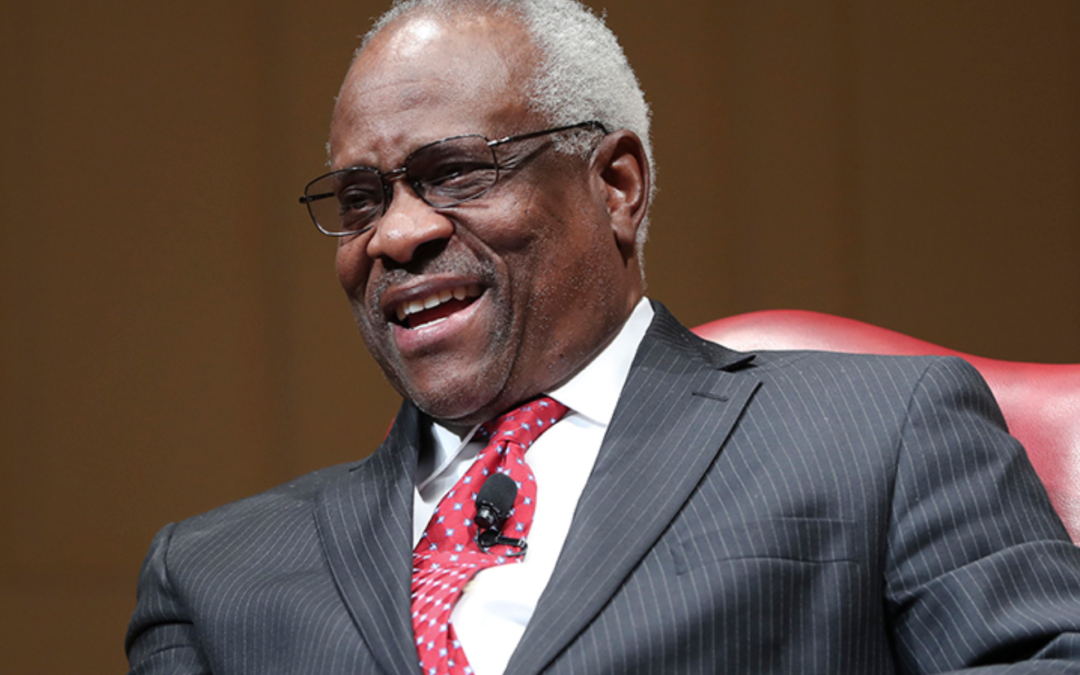

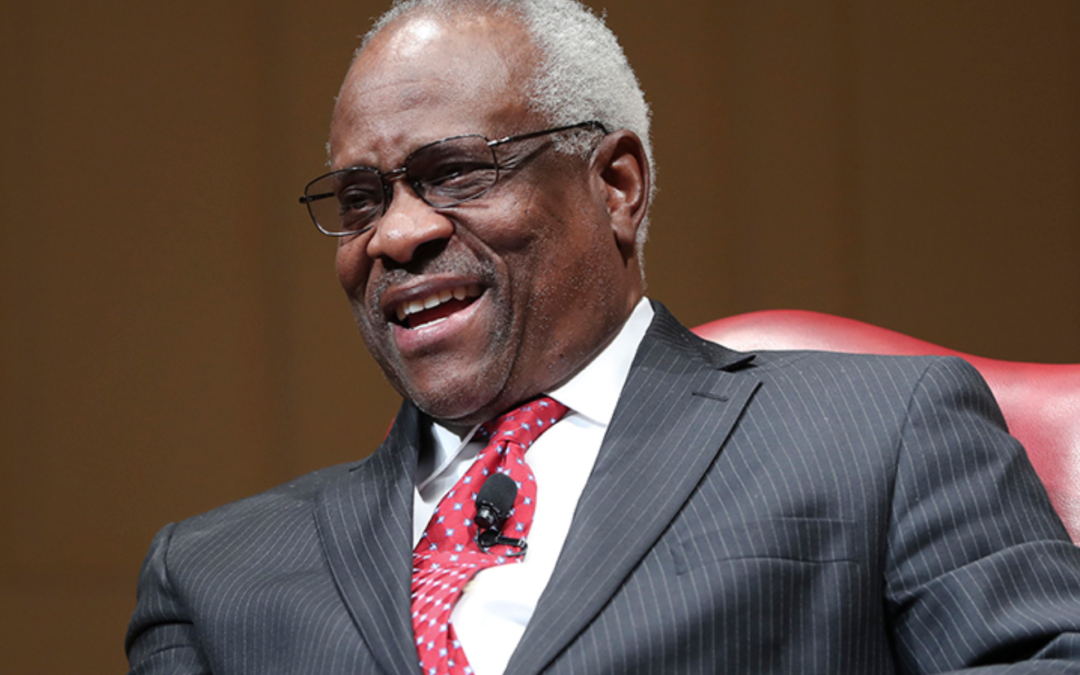

Justice Clarence Thomas, the member of the Supreme Court known for his reticence, speaks for much of a new two-hour documentary about his life.

Part of the story he tells in “Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words” centers on his longtime Catholic faith — nurtured by his grandfather who raised him in his Georgia home, nuns who taught him in school and people who prayed with him during his confirmation process to serve on the nation’s highest court.

Producer/director Michael Pack interviewed Thomas and his wife, Virginia “Ginni” Thomas, for 30 hours for the film that is currently in 20 cities, including Washington, New York, Atlanta, Chicago and Los Angeles. Pack recently served as president of Claremont Institute, a conservative think tank, but has produced documentaries for PBS about George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and “God and the Inner City.”

He talked to Religion News Service about what he learned about Thomas’ religious life as he filmed his latest documentary. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What struck you most about Clarence Thomas’ faith?

I’m struck by the depth of Clarence Thomas’ faith. It was strong when he first had it, but when you have a faith, lose your faith and come back to your faith, in some ways it’s stronger then. I’m also impressed at how Justice Thomas relies on his faith to get him through the difficult and dark moments of his life, especially his contentious confirmation hearing.

Could you talk about the role of his grandfather and how the Bible shaped his philosophy and the lessons he passed on to Thomas?

Thomas’ grandfather was functionally illiterate. So what he would do with the Bible is he would try to get a few words by heart and rely on those. The values he gave to Clarence Thomas, he felt were rooted in the Bible: working from sun to sun, never quitting, being true to yourself.

In addition to his grandfather, Thomas cites the influence of nuns at a segregated Catholic school he attended.

As he says in the documentary, he felt that they loved him and he worked hard to live up to that. And even though it was segregated Savannah, he felt they were on his side. They believed in these young boys and girls. And he adopted the faith they instilled in him. He continued to visit those nuns until several of them passed away.

He has spoken in the past about wanting to be a priest at a young age, and he attended seminary before he went to college. What drew him to seminary life?

That’s right. He went first to a minor seminary for his last year of high school and then he went to a seminary for his first year of college so he went to two different seminaries. He loved the ritual. He loved the prayers. He loved the Gregorian chant. I think he loved the entire religious environment that he lived in. He found it appealing. It spoke to something deep in his soul.

He ended up leaving that second seminary. Why?

It was racist incidents. We tell a story in which he was in one class where some kid passed him a folded note and on the front of the folded note it said “I like Martin Luther King Jr.” You open it up and it said “dead.”

This sort of mockery of somebody he thought was important and of the civil rights movement was upsetting to Justice Thomas. But it confirmed his feeling that the Catholic Church wasn’t doing enough for civil rights. And don’t forget this is the late ’60s and he’s swept up in the mood of the times as well. It’s the time of black power, of rebellion, of urban riot and, I’d say, that as a young man, Justice Thomas got caught up in those ideas too.

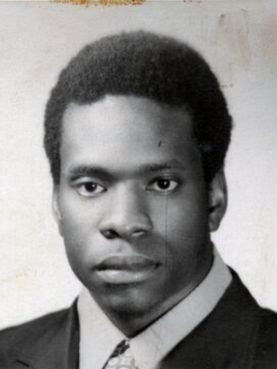

Clarence Thomas’s yearbook picture from Holy Cross College, 1969-1970. Photo courtesy of Leola Williams

How does that fit with his attendance at College of the Holy Cross?

I think that he felt he had no alternative but to go to Holy Cross. His grandfather had kicked him out of his home. He had no job. He happened to have applied to Holy Cross and had a full scholarship. So he went. But he, as soon as he got there, he hung around with Marxist students, black radicals that didn’t take religion all that seriously — even if they were at Holy Cross — so he went through a period of time where he wasn’t going to church and he wasn’t thinking about religion.

After the King assassination, Thomas said that race was his religion. But he had a turnabout in his faith again.

That’s right. He participated in an anti-war demonstration that got violent in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he got swept up in the mob violence of the moment and he watched himself being swept up and did not like what he saw. By the time that was over and he returned to Holy Cross, it was well past midnight and everything was closed, but he went to the chapel where he had not prayed in a long time. He knelt in front of the chapel and prayed for God to take anger out of his heart. And that was the beginning of his return to his faith.

While working for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Thomas delved into the history of law and particularly noted a reference to equality in the Declaration of Independence. How did those words shape his thinking about law and life?

Justice Thomas felt that the words of the declaration, “all men are created equal” and that they’re “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights,” that these truths pointed to a deep basis of American life and of the Constitution. And I think that underpins his jurisprudence today.

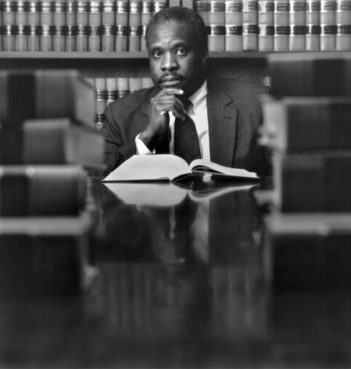

Justice Clarence Thomas sits at his desk. Photo courtesy of Justice Thomas

How has he applied that to court decisions?

His sense of what equality means underlies his jurisprudence in the Grutter decision on affirmative action. Justice Thomas was saying, I believe, that every man has that right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, to succeed or fail on their own. And he felt that the affirmative action that was under discussion in the Grutter opinion was not doing that, that there were two sets of criteria for different kinds of people and he felt that was unjust in the sense that the declaration points to justice.

What role did faith play in his life as he was being considered for the Supreme Court amid allegations that he sexually harassed onetime colleague Anita Hill?

His confirmation battle had two parts and the first part was closer to a traditional confirmation battle. After that the Anita Hill allegations of sexual harassment were leaked and that leak caused the Senate Judiciary Committee to reconvene and hold several more days of hearings. And that second time, he and Ginni felt it was a spiritual battle and they felt, rather than relying on their political skills or intellectual skills, they were relying a lot on their faith to get them through.

There is a brief mention of the “prayer partners” that were important to them at that time. Did he say more about that?

They needed to pray with other people to sort of be in touch with their faith during that second part of the hearing. He needed to be sustained by prayer and by prayer with other people as well. And because the media camped out in front of his house, it was easier for people to come to his house than for him to go out to a church.

Is there anything else about his faith that ended up on the cutting room floor?

He’s always coming back to the nuns. We portray his going to parochial school at the time that it happens in his biography. But in my talking to him, he’s always talking about what his grandfather and the nuns taught him at many points in his life. It’s a touchstone that he goes back to.

by Eduardo Campos Lima, RNS | Dec 13, 2019 | Headline News |

Members of black brotherhoods participate in a service at the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men in Salvador, Brazil. Courtesy photo by William Justo

At the end of October, members of Brazil’s Catholic black lay associations gathered in the northern port city of Salvador to discuss their centuries-long history and the challenges facing the new network they have formed — an association of associations — in a country where the Catholic Church itself is questioning its future.

Created by slaves and emancipated black men and women in colonial times, when they were not allowed to attend the same churches as their white masters, the black lay associations were once refuges of solidarity and resistance against slavery. Most made efforts to buy freedom for their enslaved members. “Our brotherhood functioned as an important center in the abolitionist struggle,” said Antônio Nicanor, a member of the Brotherhood of the Black Men in Salvador.

But the existence of the black Catholic groups is threatened by the same societal forces that are draining all established religions of members and energy, chiefly the loss of young people. “The average age in our brotherhood is 55,” Nicanor told Religion News Service. “In most of the organizations all over Brazil, there’s no effective renewal.

“Since 2017 we’ve been working to reunite all brotherhoods and communities in Brazil, in an effort to grow stronger,” said Nicanor, referring to the network that is meant to bolster brotherhoods like his. “Our organizations are aging, and we have to fight against their end.”

Some of the decline has to do with problems particular to Brazil’s complex religious landscape. The lay associations have long been concerned with the conservation of African culture in the church, and many members are loyal both to Catholicism and to Afro-Brazilian religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda. These allegiances have caused some Catholic clergy to regard them with suspicion.

“We still suffer with the prejudice of some people in the Church,” said Analia Santana, a member of Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men and an academic researcher specializing in its history.

“Many priests say they don’t know anything about the black brotherhoods. Seminaries don’t talk about us. What happens if a priest like this is suddenly appointed as our chaplain?” asked Vanilda Silvério, vice-director of the Brotherhood Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men, in São Paulo.

Members of black brotherhoods, which include both men and women, attend a service at the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men in Salvador, Brazil. Courtesy photo by William Justo

(In Portuguese, the term for these communities, “irmandade,” encompasses both men and women, though it is often rendered as “brotherhood” in English, and many specify black men in their titles. Even so, women such as Silvério have only served in leadership roles since the early 2000s.)

Her association has existed in São Paulo since 1711 and counted more than 400 members a few decades ago. Now there are 62 brothers and sisters. “My grandfather joined the brotherhood in the 1920s. Now one of my daughters is also a member,” said Silvério.

Her younger daughter, however, resists the idea of taking part in the group. “I’m 57. I’m worried about the future. I don’t see many young people joining the brotherhood. They don’t have time to contribute — they have to study and work.”

Like many shrinking institutions, Brazil’s lay Catholic associations both benefit from an infrastructure built up during their high times and pay dearly to maintain it. Most of the black fraternities own their churches, cemeteries and other historical buildings and are responsible for their conservation.

They also manage investment funds set aside for these properties’ preservation, for association activities and to pay a few employees, but the members generally lack the financial expertise to do so, according to the Rev. Lázaro Muniz, who was chaplain of the Brotherhood of the Black Men for seven years until early 2019.

During his tenure, Muniz created an archdiocesan commission in Salvador in order to keep up with the brotherhoods’ activities. “They’re independent entities, but we struggled to help them reform their bylaws and make several changes for their own good. Several fraternities had to close due to management problems. Our struggle is to preserve them,” he explained.

He was also one of the proponents of the national network of black Catholic lay associations founded three years ago.

“We hope very much this network will strengthen the brotherhoods. The meetings were very successful, and many of them are already in the process of reorganization,” he said. He added that they are forging bonds with the Afro-Brazilian pastoral commissions in their dioceses that deal with black churchgoers.

Over 500 years, the lay associations have weathered changes in the Church and the larger culture. Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men, probably the oldest black brotherhood still active in Brazil, shows up in official records in 1685, but there’s evidence it was created in 1604, according to Santana. Their staying power gives current members hope.

“Our brotherhood was always able to dialogue with the changing times and to renew itself. Many other entities had to close their doors throughout the centuries,” Santana explained.

They also have the advantage of being deeply rooted in the lives of rural communities. Though many brotherhoods originated in Salvador, Brazil’s first capital city and still its premier archdiocese, they soon spread across the country. They have long organized annual festivities in honor of their saints of devotion — black saints like Saint Benedict the Moor, Saint Elesbaan, Saint Ephigenia of Ethiopia and Saint Anthony of Carthage, who incorporated elements of the residents’ original African cultures.

These highly ritualized festivities, known as congadas, included the coronation of a king and a queen of the brotherhood. Although many of the urban fraternities don’t organize congadas anymore, they still can be seen in the countryside.

It is this kind of local religious culture that got favorable attention at the recent Synod for the Pan-Amazon Region, where Pope Francis urged bishops to reflect on “enculturation,” as the Church calls adaptation of Christianity to local contexts. Muniz believes this kind of thinking may be helpful in renovation of the Brazilian brotherhoods.

“This moment invites the fraternities to search for news ways, assuming a path of evangelization and offering possibilities for the youth to assume their traditions.”

For Nicanor, the black lay associations still have a contribution to make for a church that, guided by Francis, is looking for more lay involvement. “The church needs to feel that it’s the lay people who make Catholicism and not the clergy,” he said.

At the end of October, members of Brazil’s Catholic black lay associations gathered in the northern port city of Salvador to discuss their centuries-long history and the challenges facing the new network they have formed — an association of associations — in a country where the Catholic Church itself is questioning its future.

Created by slaves and emancipated black men and women in colonial times, when they were not allowed to attend the same churches as their white masters, the black lay associations were once refuges of solidarity and resistance against slavery. Most made efforts to buy freedom for their enslaved members. “Our brotherhood functioned as an important center in the abolitionist struggle,” said Antônio Nicanor, a member of the Brotherhood of the Black Men in Salvador.

But the existence of the black Catholic groups is threatened by the same societal forces that are draining all established religions of members and energy, chiefly the loss of young people. “The average age in our brotherhood is 55,” Nicanor told Religion News Service. “In most of the organizations all over Brazil, there’s no effective renewal.

“Since 2017 we’ve been working to reunite all brotherhoods and communities in Brazil, in an effort to grow stronger,” said Nicanor, referring to the network that is meant to bolster brotherhoods like his. “Our organizations are aging, and we have to fight against their end.”

Some of the decline has to do with problems particular to Brazil’s complex religious landscape. The lay associations have long been concerned with the conservation of African culture in the church, and many members are loyal both to Catholicism and to Afro-Brazilian religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda. These allegiances have caused some Catholic clergy to regard them with suspicion.

“We still suffer with the prejudice of some people in the Church,” said Analia Santana, a member of Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men and an academic researcher specializing in its history.

“Many priests say they don’t know anything about the black brotherhoods. Seminaries don’t talk about us. What happens if a priest like this is suddenly appointed as our chaplain?” asked Vanilda Silvério, vice-director of the Brotherhood Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men, in São Paulo.

Members of black brotherhoods, which include both men and women, attend a service at the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men in Salvador, Brazil. Courtesy photo by William Justo

(In Portuguese, the term for these communities, “irmandade,” encompasses both men and women, though it is often rendered as “brotherhood” in English, and many specify black men in their titles. Even so, women such as Silvério have only served in leadership roles since the early 2000s.)

Her association has existed in São Paulo since 1711 and counted more than 400 members a few decades ago. Now there are 62 brothers and sisters. “My grandfather joined the brotherhood in the 1920s. Now one of my daughters is also a member,” said Silvério.

Her younger daughter, however, resists the idea of taking part in the group. “I’m 57. I’m worried about the future. I don’t see many young people joining the brotherhood. They don’t have time to contribute — they have to study and work.”

Like many shrinking institutions, Brazil’s lay Catholic associations both benefit from an infrastructure built up during their high times and pay dearly to maintain it. Most of the black fraternities own their churches, cemeteries and other historical buildings and are responsible for their conservation.

They also manage investment funds set aside for these properties’ preservation, for association activities and to pay a few employees, but the members generally lack the financial expertise to do so, according to the Rev. Lázaro Muniz, who was chaplain of the Brotherhood of the Black Men for seven years until early 2019.

During his tenure, Muniz created an archdiocesan commission in Salvador in order to keep up with the brotherhoods’ activities. “They’re independent entities, but we struggled to help them reform their bylaws and make several changes for their own good. Several fraternities had to close due to management problems. Our struggle is to preserve them,” he explained.

He was also one of the proponents of the national network of black Catholic lay associations founded three years ago.

“We hope very much this network will strengthen the brotherhoods. The meetings were very successful, and many of them are already in the process of reorganization,” he said. He added that they are forging bonds with the Afro-Brazilian pastoral commissions in their dioceses that deal with black churchgoers.

Over 500 years, the lay associations have weathered changes in the Church and the larger culture. Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men, probably the oldest black brotherhood still active in Brazil, shows up in official records in 1685, but there’s evidence it was created in 1604, according to Santana. Their staying power gives current members hope.

“Our brotherhood was always able to dialogue with the changing times and to renew itself. Many other entities had to close their doors throughout the centuries,” Santana explained.

They also have the advantage of being deeply rooted in the lives of rural communities. Though many brotherhoods originated in Salvador, Brazil’s first capital city and still its premier archdiocese, they soon spread across the country. They have long organized annual festivities in honor of their saints of devotion — black saints like Saint Benedict the Moor, Saint Elesbaan, Saint Ephigenia of Ethiopia and Saint Anthony of Carthage, who incorporated elements of the residents’ original African cultures.

These highly ritualized festivities, known as congadas, included the coronation of a king and a queen of the brotherhood. Although many of the urban fraternities don’t organize congadas anymore, they still can be seen in the countryside.

It is this kind of local religious culture that got favorable attention at the recent Synod for the Pan-Amazon Region, where Pope Francis urged bishops to reflect on “enculturation,” as the Church calls adaptation of Christianity to local contexts. Muniz believes this kind of thinking may be helpful in renovation of the Brazilian brotherhoods.

“This moment invites the fraternities to search for news ways, assuming a path of evangelization and offering possibilities for the youth to assume their traditions.”

For Nicanor, the black lay associations still have a contribution to make for a church that, guided by Francis, is looking for more lay involvement. “The church needs to feel that it’s the lay people who make Catholicism and not the clergy,” he said.

by Eduardo Campos Lima, RNS | Dec 12, 2019 | Headline News |

Members of black brotherhoods participate in a service at the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men in Salvador, Brazil. Courtesy photo by William Justo

At the end of October, members of Brazil’s Catholic black lay associations gathered in the northern port city of Salvador to discuss their centuries-long history and the challenges facing the new network they have formed — an association of associations — in a country where the Catholic Church itself is questioning its future.

Created by slaves and emancipated black men and women in colonial times, when they were not allowed to attend the same churches as their white masters, the black lay associations were once refuges of solidarity and resistance against slavery. Most made efforts to buy freedom for their enslaved members. “Our brotherhood functioned as an important center in the abolitionist struggle,” said Antônio Nicanor, a member of the Brotherhood of the Black Men in Salvador.

But the existence of the black Catholic groups is threatened by the same societal forces that are draining all established religions of members and energy, chiefly the loss of young people. “The average age in our brotherhood is 55,” Nicanor told Religion News Service. “In most of the organizations all over Brazil, there’s no effective renewal.

“Since 2017 we’ve been working to reunite all brotherhoods and communities in Brazil, in an effort to grow stronger,” said Nicanor, referring to the network that is meant to bolster brotherhoods like his. “Our organizations are aging, and we have to fight against their end.”

Some of the decline has to do with problems particular to Brazil’s complex religious landscape. The lay associations have long been concerned with the conservation of African culture in the church, and many members are loyal both to Catholicism and to Afro-Brazilian religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda. These allegiances have caused some Catholic clergy to regard them with suspicion.

“We still suffer with the prejudice of some people in the Church,” said Analia Santana, a member of Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men and an academic researcher specializing in its history.

“Many priests say they don’t know anything about the black brotherhoods. Seminaries don’t talk about us. What happens if a priest like this is suddenly appointed as our chaplain?” asked Vanilda Silvério, vice-director of the Brotherhood Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men, in São Paulo.

Members of black brotherhoods, which include both men and women, attend a service at the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men in Salvador, Brazil. Courtesy photo by William Justo

(In Portuguese, the term for these communities, “irmandade,” encompasses both men and women, though it is often rendered as “brotherhood” in English, and many specify black men in their titles. Even so, women such as Silvério have only served in leadership roles since the early 2000s.)

Her association has existed in São Paulo since 1711 and counted more than 400 members a few decades ago. Now there are 62 brothers and sisters. “My grandfather joined the brotherhood in the 1920s. Now one of my daughters is also a member,” said Silvério.

Her younger daughter, however, resists the idea of taking part in the group. “I’m 57. I’m worried about the future. I don’t see many young people joining the brotherhood. They don’t have time to contribute — they have to study and work.”

Like many shrinking institutions, Brazil’s lay Catholic associations both benefit from an infrastructure built up during their high times and pay dearly to maintain it. Most of the black fraternities own their churches, cemeteries and other historical buildings and are responsible for their conservation.

They also manage investment funds set aside for these properties’ preservation, for association activities and to pay a few employees, but the members generally lack the financial expertise to do so, according to the Rev. Lázaro Muniz, who was chaplain of the Brotherhood of the Black Men for seven years until early 2019.

During his tenure, Muniz created an archdiocesan commission in Salvador in order to keep up with the brotherhoods’ activities. “They’re independent entities, but we struggled to help them reform their bylaws and make several changes for their own good. Several fraternities had to close due to management problems. Our struggle is to preserve them,” he explained.

He was also one of the proponents of the national network of black Catholic lay associations founded three years ago.

“We hope very much this network will strengthen the brotherhoods. The meetings were very successful, and many of them are already in the process of reorganization,” he said. He added that they are forging bonds with the Afro-Brazilian pastoral commissions in their dioceses that deal with black churchgoers.

Over 500 years, the lay associations have weathered changes in the Church and the larger culture. Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men, probably the oldest black brotherhood still active in Brazil, shows up in official records in 1685, but there’s evidence it was created in 1604, according to Santana. Their staying power gives current members hope.

“Our brotherhood was always able to dialogue with the changing times and to renew itself. Many other entities had to close their doors throughout the centuries,” Santana explained.

They also have the advantage of being deeply rooted in the lives of rural communities. Though many brotherhoods originated in Salvador, Brazil’s first capital city and still its premier archdiocese, they soon spread across the country. They have long organized annual festivities in honor of their saints of devotion — black saints like Saint Benedict the Moor, Saint Elesbaan, Saint Ephigenia of Ethiopia and Saint Anthony of Carthage, who incorporated elements of the residents’ original African cultures.

These highly ritualized festivities, known as congadas, included the coronation of a king and a queen of the brotherhood. Although many of the urban fraternities don’t organize congadas anymore, they still can be seen in the countryside.

It is this kind of local religious culture that got favorable attention at the recent Synod for the Pan-Amazon Region, where Pope Francis urged bishops to reflect on “enculturation,” as the Church calls adaptation of Christianity to local contexts. Muniz believes this kind of thinking may be helpful in renovation of the Brazilian brotherhoods.

“This moment invites the fraternities to search for news ways, assuming a path of evangelization and offering possibilities for the youth to assume their traditions.”

For Nicanor, the black lay associations still have a contribution to make for a church that, guided by Francis, is looking for more lay involvement. “The church needs to feel that it’s the lay people who make Catholicism and not the clergy,” he said.

At the end of October, members of Brazil’s Catholic black lay associations gathered in the northern port city of Salvador to discuss their centuries-long history and the challenges facing the new network they have formed — an association of associations — in a country where the Catholic Church itself is questioning its future.

Created by slaves and emancipated black men and women in colonial times, when they were not allowed to attend the same churches as their white masters, the black lay associations were once refuges of solidarity and resistance against slavery. Most made efforts to buy freedom for their enslaved members. “Our brotherhood functioned as an important center in the abolitionist struggle,” said Antônio Nicanor, a member of the Brotherhood of the Black Men in Salvador.

But the existence of the black Catholic groups is threatened by the same societal forces that are draining all established religions of members and energy, chiefly the loss of young people. “The average age in our brotherhood is 55,” Nicanor told Religion News Service. “In most of the organizations all over Brazil, there’s no effective renewal.

“Since 2017 we’ve been working to reunite all brotherhoods and communities in Brazil, in an effort to grow stronger,” said Nicanor, referring to the network that is meant to bolster brotherhoods like his. “Our organizations are aging, and we have to fight against their end.”

Some of the decline has to do with problems particular to Brazil’s complex religious landscape. The lay associations have long been concerned with the conservation of African culture in the church, and many members are loyal both to Catholicism and to Afro-Brazilian religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda. These allegiances have caused some Catholic clergy to regard them with suspicion.

“We still suffer with the prejudice of some people in the Church,” said Analia Santana, a member of Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men and an academic researcher specializing in its history.

“Many priests say they don’t know anything about the black brotherhoods. Seminaries don’t talk about us. What happens if a priest like this is suddenly appointed as our chaplain?” asked Vanilda Silvério, vice-director of the Brotherhood Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men, in São Paulo.

Members of black brotherhoods, which include both men and women, attend a service at the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary of the Black Men in Salvador, Brazil. Courtesy photo by William Justo

(In Portuguese, the term for these communities, “irmandade,” encompasses both men and women, though it is often rendered as “brotherhood” in English, and many specify black men in their titles. Even so, women such as Silvério have only served in leadership roles since the early 2000s.)

Her association has existed in São Paulo since 1711 and counted more than 400 members a few decades ago. Now there are 62 brothers and sisters. “My grandfather joined the brotherhood in the 1920s. Now one of my daughters is also a member,” said Silvério.

Her younger daughter, however, resists the idea of taking part in the group. “I’m 57. I’m worried about the future. I don’t see many young people joining the brotherhood. They don’t have time to contribute — they have to study and work.”

Like many shrinking institutions, Brazil’s lay Catholic associations both benefit from an infrastructure built up during their high times and pay dearly to maintain it. Most of the black fraternities own their churches, cemeteries and other historical buildings and are responsible for their conservation.

They also manage investment funds set aside for these properties’ preservation, for association activities and to pay a few employees, but the members generally lack the financial expertise to do so, according to the Rev. Lázaro Muniz, who was chaplain of the Brotherhood of the Black Men for seven years until early 2019.

During his tenure, Muniz created an archdiocesan commission in Salvador in order to keep up with the brotherhoods’ activities. “They’re independent entities, but we struggled to help them reform their bylaws and make several changes for their own good. Several fraternities had to close due to management problems. Our struggle is to preserve them,” he explained.

He was also one of the proponents of the national network of black Catholic lay associations founded three years ago.

“We hope very much this network will strengthen the brotherhoods. The meetings were very successful, and many of them are already in the process of reorganization,” he said. He added that they are forging bonds with the Afro-Brazilian pastoral commissions in their dioceses that deal with black churchgoers.

Over 500 years, the lay associations have weathered changes in the Church and the larger culture. Nicanor’s Brotherhood of the Black Men, probably the oldest black brotherhood still active in Brazil, shows up in official records in 1685, but there’s evidence it was created in 1604, according to Santana. Their staying power gives current members hope.

“Our brotherhood was always able to dialogue with the changing times and to renew itself. Many other entities had to close their doors throughout the centuries,” Santana explained.

They also have the advantage of being deeply rooted in the lives of rural communities. Though many brotherhoods originated in Salvador, Brazil’s first capital city and still its premier archdiocese, they soon spread across the country. They have long organized annual festivities in honor of their saints of devotion — black saints like Saint Benedict the Moor, Saint Elesbaan, Saint Ephigenia of Ethiopia and Saint Anthony of Carthage, who incorporated elements of the residents’ original African cultures.

These highly ritualized festivities, known as congadas, included the coronation of a king and a queen of the brotherhood. Although many of the urban fraternities don’t organize congadas anymore, they still can be seen in the countryside.

It is this kind of local religious culture that got favorable attention at the recent Synod for the Pan-Amazon Region, where Pope Francis urged bishops to reflect on “enculturation,” as the Church calls adaptation of Christianity to local contexts. Muniz believes this kind of thinking may be helpful in renovation of the Brazilian brotherhoods.

“This moment invites the fraternities to search for news ways, assuming a path of evangelization and offering possibilities for the youth to assume their traditions.”

For Nicanor, the black lay associations still have a contribution to make for a church that, guided by Francis, is looking for more lay involvement. “The church needs to feel that it’s the lay people who make Catholicism and not the clergy,” he said.