Juneteenth: Freedom’s promise is still denied to thousands of blacks unable to make bail

Video Courtesy of The Root

June 19 marks Juneteenth, a celebration of the de facto end of slavery in the United States.

For hundreds of thousands of African-Americans stuck in pretrial detention – accused but not convicted of a crime, and unable to leave because of bail – that promise remains unfulfilled. And coming immediately before Father’s Day, it’s also a reminder of the loss associated with the forced separation of families.

On a very personal level, I know how this separation feels. Every Father’s Day since 2011, I’ve been reminded of the unexpected death of my dad at the age of 48. But also on a professional level, as a criminologist who has been researching mass incarceration for the past decade, I understand the disproportionate impact it’s had on African-Americans, destabilizing black families in the process.

Blacks behind bars

Juneteenth is a celebration of African-Americans’ triumph over slavery and access to freedom in the U.S., which occurred in Galveston, Texas, in June of 1865, over two and a half years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

While Juneteenth is a momentous day in U.S. history, it is important to appreciate that the civil rights and liberties promised to African-Americans have yet to be fully realized. As legal scholar Michelle Alexander forcefully explains, this is a consequence of Jim Crow laws and the proliferation of incarceration that began in the 1970s, including the increase of people placed in pretrial detention and other criminal justice policies.

There are 2.3 million people currently incarcerated in American prisons and jails – including those not convicted of any crime. Black people comprise 40 percent of them, even though they represent just 13 percent of the U.S. population.

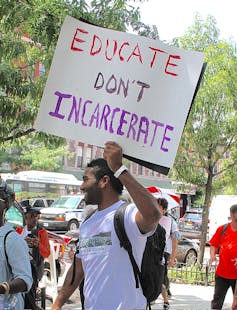

Protesters march through Harlem in the March for Justice. Rainmaker Photo/MediaPunch/IPX

Not yet guilty but not free

More troubling is the number of incarcerated individuals currently held in jail for crimes of which they have not yet been convicted.

The Prison Policy Initiative, a nonpartisan think tank that focuses on mass incarceration, has reported that over a half million citizens are languishing in pretrial detention. And like most criminal justice outcomes, the burden of this disproportionately falls on minorities, especially black men and women.

In local jails alone, over 300,000 people are awaiting trial for property, drug or public order crimes. And again, these disproportionately black defendants are confined and separated from their families, friends and jobs simply because they lack the means to post cash bail – the only reason they can’t get out.

Toll on families

It should be no surprise, then, that 1 in 9 black children now has a parent behind bars, compared with the national rate of 1 in 28.

And many of these children are at an increased likelihood of experiencing physical and mental health issues, academic struggles and a range of other behavioral problems. Children of incarcerated mothers are also at heightened odds of ending up in foster care and being exposed to other traumas.

Being the partner of an incarcerated individual is another often stressful experience that also falls disproportionately on black citizens, particularly women.

Some good news

The good news is that such injustices are receiving growing attention nationwide.

Just City, a nonprofit organization working to reduce the harms of the criminal justice system, has campaigned to raise funds and promote awareness of its Memphis Community Bail Fund project for Father’s Day – in part because nearly half a million of the black men behind bars are dads.

The aim of the project is to provide both financial and legal support for defendants lacking resources to independently secure their pretrial release, with the goal of the campaign being the release of jailed fathers so that they could be with their kids for the holiday.

Bail funds similar to Just City’s have proliferated throughout the U.S.

On one hand, the multiplication of these organizations is encouraging and reason for optimism. On the other, their growth is another reminder that many of the freedoms celebrated on Juneteenth remain unrealized.

A long road continues

In cities like Detroit, where 1 in 7 adult males is under some form of correctional control in some communities, it is a monumental task to make sense of the short- and long-term impacts of incarceration for black families.

Children suffer. Parents struggle. Relationships deteriorate. And as a result, so too do so many African-American communities. Lost wages matter to families, but they also matter to communities. The lower tax base that results makes it more difficult for struggling public institutions, like schools, to progress. And with such a large share of individuals removed from some communities due to incarceration, and branded as felons upon their release, these communities lose potential voters and the political capital they carry. They are too often disenfranchised and stripped of their full power and potential.

Juneteenth celebrates the freedom of black Americans and the long, hard road they were forced to traverse to gain that freedom. But as criminologists like me have maintained time and again, the U.S. criminal justice system remains biased, albeit implicitly, against them.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.