Let America be America again

Video Courtesy of Charles Belfor

A leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, the inspiration behind Lorraine Hansberry’s play “A Raisin in the Sun” and an uncompromising voice for social justice, Langston Hughes is heralded as one of America’s greatest poets.

It wasn’t always this way. During his career, Hughes was routinely harassed by his own government. And the nation’s literati, balking at his subversive politics, tended to overlook his work.

But the opposite was true abroad, in places like France, Nigeria and Cuba, where Hughes had legions of devoted readers who were some of the first to recognize the promise and power of the poet’s words. In my new book, “Langston Hughes: Critical Lives,” I trace Hughes’ budding international stardom, and how it clashed with the hostility he faced back home.

Building a fan base

Growing up in America, Hughes had experienced racism firsthand. As he matured as poet and writer, he started looking beyond America’s borders, curious to learn more about how racism impacted different cultures.

Between 1924 and his death in 1967, Hughes made trips to places as varied as Italy, Russia, England, Nigeria and Ghana.

During a visit to Cuba in 1930, Hughes met a young Cuban poet named Nicolás Guillén. Hughes had already successfully written dozens of poems inspired by the 12-bar structures, cadences, rhymes and subject matter of blues music. Over the course of several late-night dinners at Lolita’s restaurant in Havana, Hughes encouraged Guillén to do the same with his home country’s music.

Within days of Hughes’ departure, Guillén started writing poems making use of Cuba’s “son tradition,” a form of popular dance music. This was a key moment in the development of an artist who would go on to become Cuba’s national poet.

Hughes was also the only figure of the Harlem Renaissance who traveled to Africa. After several trips to the continent, he became determined to promote the work of his African peers – writers like Bloke Modisane and eventual Nobel Prize-winner Wole Soyinka. So in 1960, he edited his anthology “African Treasury,” which introduced many in the West to some of Africa’s greatest writers.

In countries like Nigeria, Hughes needed no introduction. In the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, dozens of Hughes’ poems had appeared in the country’s newspapers and journals. After Nigeria elected Nnamdi Azikiwe, its first native governor-general, in 1960, Azikiwe concluded his inaugural by reciting Hughes’ poem “Youth.”

When Hughes returned to Ghana and Senegal later in the decade, he was greeted like a superstar. Scores of his admirers trailed him in the streets of Dakar, much in the way sports heroes are hounded by children for autographs.

By the 1960s, Hughes’ works were being translated into Russian, Italian, Swedish and Spanish. But the first scholarly study of his poetry appeared in France. Literary critic Jean Wagner’s 1963 book “Black Poets of the United States” highlighted the talents of Hughes as both a poet and activist. Devoting over 100 pages to Hughes, Wagner noted that African Americans would never “produce a more fiery bard” who was simultaneously “one of the community refusing to stand apart as an individual.”

As the first black writer in the United States to make his living solely by writing, Hughes ultimately galvanized scores of emerging writers and poets in Europe, Africa and South America. To them, Hughes represented a critical Western link to other people of color around the world. He was also an exemplar of the jazz and blues music they so revered. As a testament to Hughes’ popularity abroad, it was Venezuela – not the United States – that sought to nominate him for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1960.

Making enemies at home

Back in America, Hughes certainly had his admirers, especially among the African American community. But most establishment figures – in politics, in the media and in law enforcement – viewed him as a menace.

As Hughes’ international fame grew, he was being denigrated as a subversive and a communist by his own government. Hughes had been under FBI surveillance since at least 1933, after he had traveled to Russia. Meanwhile his adamant calls for justice in the Scottsboro case of 1931 – when eight young black men were falsely accused of raping two white prostitutes – earned him the ire of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Hughes’ piercing critiques of capitalism didn’t help his cause, either. Hoover would go on to wage a personal vendetta against Hughes, building a 550-page file on him that highlighted poems like “Goodbye, Christ” as evidence of his communist sympathies.

Then, in 1953, Hughes was called to testify before Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who wanted to use Hughes’ previous support of communist causes and his supposedly subversive allegiances to target suspected “reds” in the State Department.

The man who was exalted by political leaders overseas, who found himself elbowing his way through throngs of adoring crowds abroad, was attacked as “un-American” by McCarthy’s Senate Subcommittee.

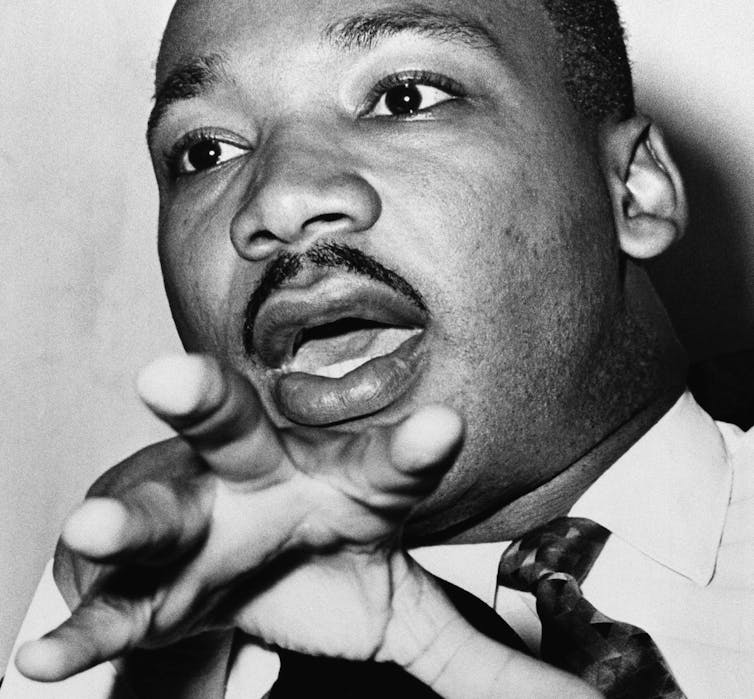

AP Photo

Hughes was understandably conflicted about his native country, and he explored this ambivalence in poems such as “Let America Be America Again”:

Let America be America again.

Let it be the dream it used to be.

Let it be the pioneer on the plain

Seeking a home where he himself is free.

(America never was America to me.)

That last line still resonates for many Americans – for those who have never known a golden age, nor tasted the nation’s promise of dreams, justice and equality for all.

How long, Hughes wondered in “Harlem,” would we have to wait? And what was the cost of kicking the can down the road?

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Interestingly, Hughes had ended the first draft of this famous poem with the lines, “or does it atom-like explode / and leave deaths in its wake? Does it disappear / as might smoke somewhere?”

Writing on Aug. 7, 1948, the poet was keenly aware of what had happened only three years prior when nuclear bombs were dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

To me, this perfectly encapsulates Hughes’ international appeal. The poet sympathized with those who had felt the harshest wrath of American power and politics. His intended audience was never just his fellow Americans who were grappling with fear and anxiety; it was anyone who had suffered great and devastating loss – an anguish that knows no language or borders.

Jason Miller, Professor of English, North Carolina State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.