by Cara Anthony, a Kaiser Health News Midwest correspondent | Dec 23, 2021 | Headline News |

When Ashlee Wisdom launched an early version of her health and wellness website, more than 34,000 users — most of them Black — visited the platform in the first two weeks.

“It wasn’t the most fully functioning platform,” recalled Wisdom, 31. “It was not sexy.”

But the launch was successful. Now, more than a year later, Wisdom’s company, Health in Her Hue, connects Black women and other women of color to culturally sensitive doctors, doulas, nurses and therapists nationally.

As more patients seek culturally competent care — the acknowledgment of a patient’s heritage, beliefs and values during treatment — a new wave of Black tech founders like Wisdom want to help. In the same way Uber Eats and Grubhub revolutionized food delivery, Black tech health startups across the United States want to change how people exercise, how they eat and how they communicate with doctors.

Inspired by their own experiences, plus those of their parents and grandparents, Black entrepreneurs are launching startups that aim to close the cultural gap in health care with technology — and create profitable businesses at the same time.

“One of the most exciting growth opportunities across health innovation is to back underrepresented founders building health companies focusing on underserved markets,” said Unity Stoakes, president and co-founder of StartUp Health, a company headquartered in San Francisco that has invested in a number of health companies led by people of color. He said those leaders have “an essential and powerful understanding of how to solve some of the biggest challenges in health care.”

Platforms created by Black founders for Black people and communities of color continue to blossom because those entrepreneurs often see problems and solutions others might miss. Without diverse voices, entire categories and products simply would not exist in critical areas like health care, business experts say.

“We’re really speaking to a need,” said Kevin Dedner, 45, founder of the mental health startup Hurdle. “Mission alone is not enough. You have to solve a problem.”

Dedner’s company, headquartered in Washington, D.C., pairs patients with therapists who “honor culture instead of ignoring it,” he said. He started the company three years ago, but more people turned to Hurdle after the killing of George Floyd.

In Memphis, Tennessee, Erica Plybeah, 33, is focused on providing transportation. Her company, MedHaul, works with providers and patients to secure low-cost rides to get people to and from their medical appointments. Caregivers, patients or providers fill out a form on MedHaul’s website, then Plybeah’s team helps them schedule a ride.

While MedHaul is for everyone, Plybeah knows people of color, anyone with a low income and residents of rural areas are more likely to face transportation hurdles. She founded the company in 2017 after years of watching her mother take care of her grandmother, who had lost two limbs to Type 2 diabetes. They lived in the Mississippi Delta, where transportation options were scarce.

“For years, my family struggled with our transportation because my mom was her primary transporter,” Plybeah said. “Trying to schedule all of her doctor’s appointments around her work schedule was just a nightmare.”

Plybeah’s company recently received funding from Citi, the banking giant.

“I’m more than proud of her,” said Plybeah’s mother, Annie Steele. “Every step amazes me. What she is doing is going to help people for many years to come.”

Health in Her Hue launched in 2018 with just six doctors on the roster. Two years later, users can download the app at no cost and then scroll through roughly 1,000 providers.

“People are constantly talking about Black women’s poor health outcomes, and that’s where the conversation stops,” said Wisdom, who lives in New York City. “I didn’t see anyone building anything to empower us.”

As her business continues to grow, Wisdom draws inspiration from friends such as Nathan Pelzer, 37, another Black tech founder, who has launched a company in Chicago. Clinify Health works with community health centers and independent clinics in underserved communities. The company analyzes medical and social data to help doctors identify their most at-risk patients and those they haven’t seen in awhile. By focusing on getting those patients preventive care, the medical providers can help them improve their health and avoid trips to the emergency room.

“You can think of Clinify Health as a company that supports triage outside of the emergency room,” Pelzer said.

Pelzer said he started the company by printing out online slideshows he’d made and throwing them in the trunk of his car. “I was driving around the South Side of Chicago, knocking on doors, saying, ‘Hey, this is my idea,’” he said.

Wisdom got her app idea from being so stressed while working a job during grad school that she broke out in hives.

“It was really bad,” Wisdom recalled. “My hand would just swell up, and I couldn’t figure out what it was.”

The breakouts also baffled her allergist, a white woman, who told Wisdom to take two Allegra every day to manage the discomfort. “I remember thinking if she was a Black woman, I might have shared a bit more about what was going on in my life,” Wisdom said.

The moment inspired her to build an online community. Her idea started off small. She found health content in academic journals, searched for eye-catching photos that would complement the text and then posted the information on Instagram.

Things took off from there. This fall, Health in Her Hue launched “care squads” for users who want to discuss their health with doctors or with other women interested in the same topics.

“The last thing you want to do when you go into the doctor’s office is feel like you have to put on an armor and feel like you have to fight the person or, like, you know, be at odds with the person who’s supposed to be helping you on your health journey,” Wisdom said. “And that’s oftentimes the position that Black people, and largely also Black women, are having to deal with as they’re navigating health care. And it just should not be the case.”

As Black tech founders, Wisdom, Dedner, Pelzer and Plybeah look for ways to support one another by trading advice, chatting about funding and looking for ways to come together. Pelzer and Wisdom met a few years ago as participants in a competition sponsored by Johnson & Johnson. They reconnected at a different event for Black founders of technology companies and decided to help each other.

“We’re each other’s therapists,” Pelzer said. “It can get lonely out here as a Black founder.”

In the future, Plybeah wants to offer transportation services and additional assistance to people caring for aging family members. She also hopes to expand the service to include dropping off customers for grocery and pharmacy runs, workouts at gyms and other basic errands.

Pelzer wants Clinify Health to make tracking health care more fun — possibly with incentives to keep users engaged. He is developing plans and wants to tap into the same competitive energy that fitness companies do.

Wisdom wants to support physicians who seek to improve their relationships with patients of color. The company plans to build a library of resources that professionals could use as a guide.

“We’re not the first people to try to solve these problems,” Dedner said. Yet he and the other three feel the pressure to succeed for more than just themselves and those who came before them.

“I feel like, if I fail, that’s potentially going to shut the door for other Black women who are trying to build in this space,” Wisdom said. “But I try not to think about that too much.”

Subscribe to KHN's free Morning Briefing.

by Cara Anthony, a Kaiser Health News Midwest correspondent | Oct 17, 2019 | Headline News |

While living in Detroit earlier this year, Brianna Snitchler wanted a cyst removed from her abdomen. But her doctor wanted the growth checked for cancer first. (Callie Richmond for KHN)

Brianna Snitchler was just figuring out the art of adulting when she scheduled a biopsy at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Snitchler was on top of her finances: Her student loan balance was down and her credit score was up.

“I had been working for the past three years trying to improve my credit and, you know, just become a functioning adult human being,” Snitchler, 27, said.

For the first time in her adult life, she had health insurance through her job and a primary care doctor she liked. Together they were working on Snitchler’s concerns about her mental and physical health.

One concern was a cyst on her abdomen. The growth was about the size of a quarter, and it didn’t hurt or particularly worry Snitchler. But it did make her self-conscious whenever she went for a swim.

“People would always call it out and be alarmed by it,” she recalled.

Before having the cyst removed, Snitchler’s doctor wanted to check the growth for cancer. After a first round of screening tests, Snitchler had an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy at Henry Ford Health System’s main hospital.

The procedure was “uneventful,” with no complications reported, according to results faxed to her primary care doctor after the procedure. The growth was indeed benign, and Snitchler thought her next step would be getting the cyst removed.

Then the bill came.

The Patient: Brianna Snitchler, 27, a user-experience designer living in Detroit at the time. As a contractor for Ford Motor Co., she had a UnitedHealthcare insurance plan.

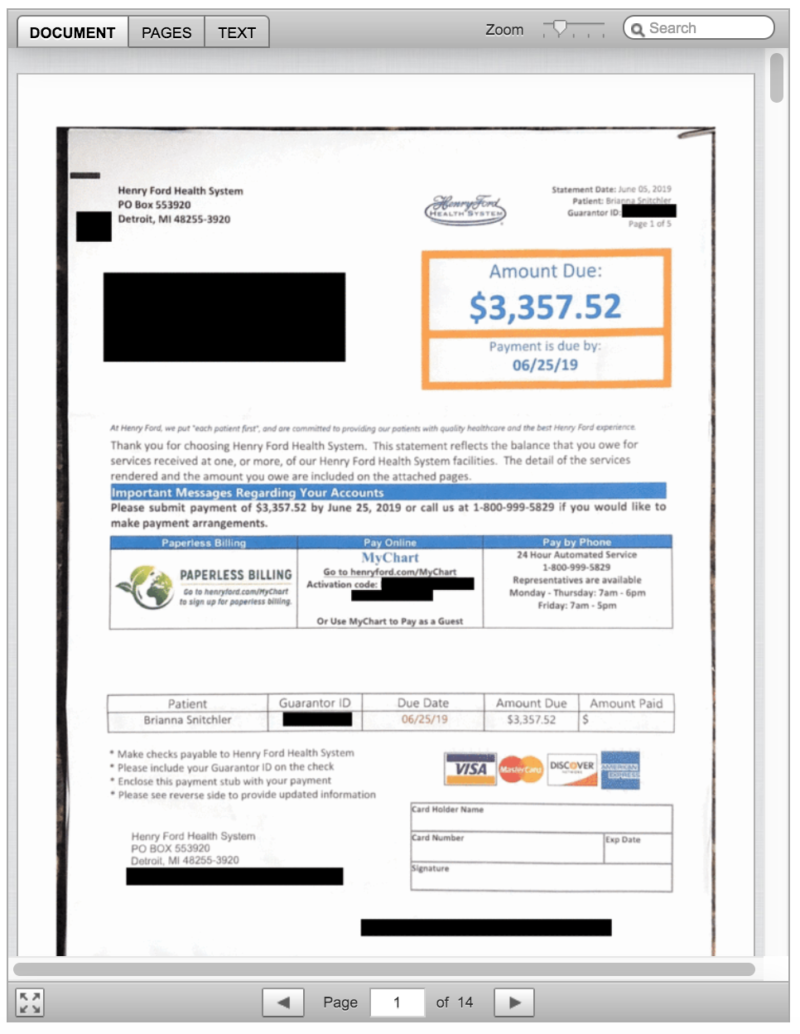

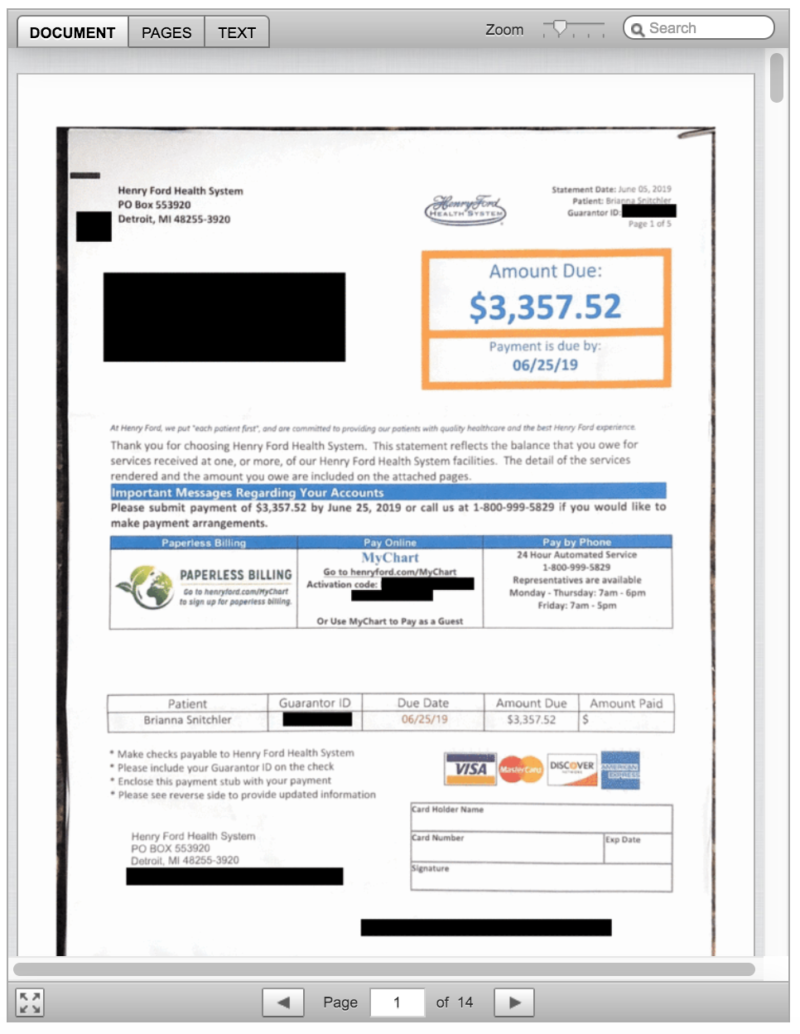

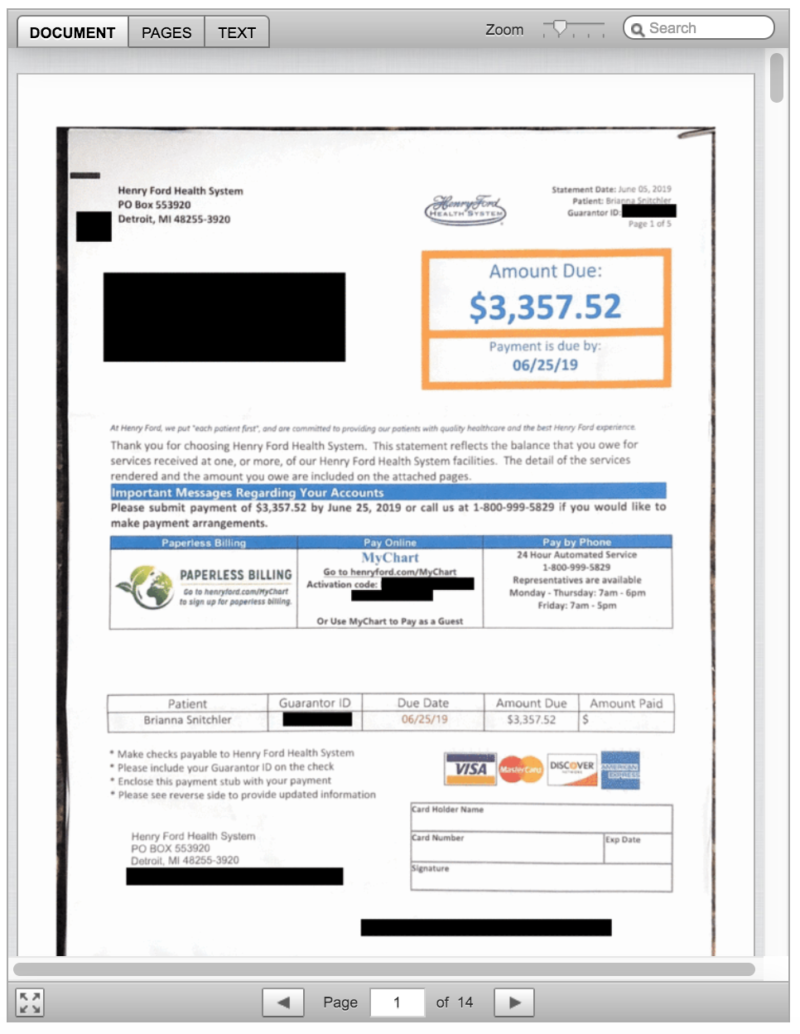

Total Bill: $3,357.52, including a $2,170 facility fee listed as “operating room services.” The balance included a biopsy, ultrasound, physician charges and lab tests.

Service Provider: Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Medical Procedure: Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of a cyst.

What Gives: When Snitchler scheduled the biopsy, no one told her that Henry Ford Health System would also charge her a $2,170 facility fee.

Snitchler said the bill turned out to be far more than what she budgeted for. Her insurance plan from UnitedHealthcare had a high-deductible of $3,250, plus she would owe coinsurance. All told, her bills for the care she received related to the biopsy left her on the hook for $3,357.52, with her insurance paying $974.

“She shrugged it off,” Snitchler’s partner, Emi Aguilar, recalled. “But I could see that she was upset in her eyes.”

Snitchler panicked when she realized the bill threatened the couple’s financial security. Snitchler had already spent down her savings for a recent cross-country move to Austin, Texas.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman David Olejarz said the “procedure was performed in the Interventional Radiology procedure room, where the imaging allows the biopsy to be much more precise.”

“We perform procedures in the most appropriate venue to ensure the highest standards of patient quality and safety,” Olejarz wrote.

The initial bill from Henry Ford referred to “operating room services.” The hospital later sent an itemized bill that referred to the charge for a treatment room in the radiology department. Both descriptions boil down to a facility fee, a common charge that has become controversial as hospitals search for additional streams of income, and as more patients complain they’ve been blindsided by these fees.

Hospital officials argue that medical centers need the boosted income to provide the expensive care sick patients require, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

But the way hospitals calculate facility fees is “a black box,” said Ted Doolittle, with the Office of the Healthcare Advocate for Connecticut, a state that has put a spotlight on the issue.

“It’s somewhat akin to a cover charge” at a club, said Doolittle, who previously served as deputy director of the federal Center for Program Integrity at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Hospitals in Connecticut billed more than $1 billion in facility fees in 2015 and 2016, according to state records. In 2015, Connecticut lawmakers approved a bill that forces all hospitals and medical providers to disclose facility fees upfront. Now patients in Connecticut “should never be charged a facility fee without being shown in burning scarlet letters that they are going to get charged this fee,” Doolittle said.

In Michigan, there’s no law requiring hospitals and other providers of health care services to inform patients of facility fees ahead of time.

Brianna Snitchler’s procedure took place on campus at Henry Ford’s main hospital site. When she got her bill, with its mention of “operating room services,” she was baffled. Snitchler said the room had “crazy medical equipment,” but she was still in her street clothes as a nurse numbed her cyst and she was sent home in a matter of minutes.

With Snitchler’s permission, Kaiser Health News shared her itemized bill, biopsy results and explanation of benefits with Dr. Mark Weiss, a radiologist who leads MediCrew, a company in Flint, Mich., that helps patients navigate the health system.

Weiss said it probably wasn’t medically necessary for Snitchler to go to the hospital to receive good care. “Not all surgical procedures have to be done at a surgical center,” he said, noting that biopsies often can be done in an office-based treatment center.

Resolution: Hoping for a reasonable explanation — or even the discovery of a mistake — Snitchler called her insurance company and the hospital.

A representative at Henry Ford told her on the phone that the hospital isn’t “legally required” to inform patients of fees ahead of time.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman Olejarz apologized for that response: “We’ll use it as a teachable moment for our staff. We are committed to being transparent with our patients about what we charge.”

He pointed to an initiative launched in 2018 that helps patients anticipate out-of-pocket expenses. The program targets the most common elective radiology and gastroenterology tests that often have high price tags for patients.

Asked if Snitchler’s ultrasound-guided needle biopsy will be included in the price transparency initiative, Olejarz replied, “Can’t say at this point.”

In addition to the pilot program to inform patients of fees, Olejarz said, the hospital also plans to roll out an online cost-estimator tool.

For now, Snitchler has decided not to get the cyst removed, and she plans to try to negotiate on her bill. She has not yet paid any portion of it.

“You should always negotiate; you should always try,” Doolittle said. “Doesn’t mean it’s going to work, but it can work. People should not be shy about it.”

“We are happy to work out a flexible payment plan that best meets her needs,” Olejarz wrote when Kaiser Health News first inquired about Snitchler’s bill.

The Takeaway: When your doctor recommends an outpatient test or procedure like a biopsy, be aware that the hospital may be the most expensive place you can have it done. Ask your physician for recommendations of where else you might have the procedure, and then call each facility to try to get an estimate of the costs you’d face.

Also, be wary of places that may look like independent doctor’s offices but are owned by a hospital. These practices also can tack hefty facility fees onto your bill.

If you get a bill that seems inflated, call your hospital and insurer and try to negotiate it down.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

by Cara Anthony, a Kaiser Health News Midwest correspondent | Oct 16, 2019 | Headline News |

While living in Detroit earlier this year, Brianna Snitchler wanted a cyst removed from her abdomen. But her doctor wanted the growth checked for cancer first. (Callie Richmond for KHN)

Brianna Snitchler was just figuring out the art of adulting when she scheduled a biopsy at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

Snitchler was on top of her finances: Her student loan balance was down and her credit score was up.

“I had been working for the past three years trying to improve my credit and, you know, just become a functioning adult human being,” Snitchler, 27, said.

For the first time in her adult life, she had health insurance through her job and a primary care doctor she liked. Together they were working on Snitchler’s concerns about her mental and physical health.

One concern was a cyst on her abdomen. The growth was about the size of a quarter, and it didn’t hurt or particularly worry Snitchler. But it did make her self-conscious whenever she went for a swim.

“People would always call it out and be alarmed by it,” she recalled.

Before having the cyst removed, Snitchler’s doctor wanted to check the growth for cancer. After a first round of screening tests, Snitchler had an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy at Henry Ford Health System’s main hospital.

The procedure was “uneventful,” with no complications reported, according to results faxed to her primary care doctor after the procedure. The growth was indeed benign, and Snitchler thought her next step would be getting the cyst removed.

Then the bill came.

The Patient: Brianna Snitchler, 27, a user-experience designer living in Detroit at the time. As a contractor for Ford Motor Co., she had a UnitedHealthcare insurance plan.

Total Bill: $3,357.52, including a $2,170 facility fee listed as “operating room services.” The balance included a biopsy, ultrasound, physician charges and lab tests.

Service Provider: Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

Medical Procedure: Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of a cyst.

What Gives: When Snitchler scheduled the biopsy, no one told her that Henry Ford Health System would also charge her a $2,170 facility fee.

Snitchler said the bill turned out to be far more than what she budgeted for. Her insurance plan from UnitedHealthcare had a high-deductible of $3,250, plus she would owe coinsurance. All told, her bills for the care she received related to the biopsy left her on the hook for $3,357.52, with her insurance paying $974.

“She shrugged it off,” Snitchler’s partner, Emi Aguilar, recalled. “But I could see that she was upset in her eyes.”

Snitchler panicked when she realized the bill threatened the couple’s financial security. Snitchler had already spent down her savings for a recent cross-country move to Austin, Texas.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman David Olejarz said the “procedure was performed in the Interventional Radiology procedure room, where the imaging allows the biopsy to be much more precise.”

“We perform procedures in the most appropriate venue to ensure the highest standards of patient quality and safety,” Olejarz wrote.

The initial bill from Henry Ford referred to “operating room services.” The hospital later sent an itemized bill that referred to the charge for a treatment room in the radiology department. Both descriptions boil down to a facility fee, a common charge that has become controversial as hospitals search for additional streams of income, and as more patients complain they’ve been blindsided by these fees.

Hospital officials argue that medical centers need the boosted income to provide the expensive care sick patients require, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

But the way hospitals calculate facility fees is “a black box,” said Ted Doolittle, with the Office of the Healthcare Advocate for Connecticut, a state that has put a spotlight on the issue.

“It’s somewhat akin to a cover charge” at a club, said Doolittle, who previously served as deputy director of the federal Center for Program Integrity at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Hospitals in Connecticut billed more than $1 billion in facility fees in 2015 and 2016, according to state records. In 2015, Connecticut lawmakers approved a bill that forces all hospitals and medical providers to disclose facility fees upfront. Now patients in Connecticut “should never be charged a facility fee without being shown in burning scarlet letters that they are going to get charged this fee,” Doolittle said.

In Michigan, there’s no law requiring hospitals and other providers of health care services to inform patients of facility fees ahead of time.

Brianna Snitchler’s procedure took place on campus at Henry Ford’s main hospital site. When she got her bill, with its mention of “operating room services,” she was baffled. Snitchler said the room had “crazy medical equipment,” but she was still in her street clothes as a nurse numbed her cyst and she was sent home in a matter of minutes.

With Snitchler’s permission, Kaiser Health News shared her itemized bill, biopsy results and explanation of benefits with Dr. Mark Weiss, a radiologist who leads MediCrew, a company in Flint, Mich., that helps patients navigate the health system.

Weiss said it probably wasn’t medically necessary for Snitchler to go to the hospital to receive good care. “Not all surgical procedures have to be done at a surgical center,” he said, noting that biopsies often can be done in an office-based treatment center.

Resolution: Hoping for a reasonable explanation — or even the discovery of a mistake — Snitchler called her insurance company and the hospital.

A representative at Henry Ford told her on the phone that the hospital isn’t “legally required” to inform patients of fees ahead of time.

In an email, Henry Ford spokesman Olejarz apologized for that response: “We’ll use it as a teachable moment for our staff. We are committed to being transparent with our patients about what we charge.”

He pointed to an initiative launched in 2018 that helps patients anticipate out-of-pocket expenses. The program targets the most common elective radiology and gastroenterology tests that often have high price tags for patients.

Asked if Snitchler’s ultrasound-guided needle biopsy will be included in the price transparency initiative, Olejarz replied, “Can’t say at this point.”

In addition to the pilot program to inform patients of fees, Olejarz said, the hospital also plans to roll out an online cost-estimator tool.

For now, Snitchler has decided not to get the cyst removed, and she plans to try to negotiate on her bill. She has not yet paid any portion of it.

“You should always negotiate; you should always try,” Doolittle said. “Doesn’t mean it’s going to work, but it can work. People should not be shy about it.”

“We are happy to work out a flexible payment plan that best meets her needs,” Olejarz wrote when Kaiser Health News first inquired about Snitchler’s bill.

The Takeaway: When your doctor recommends an outpatient test or procedure like a biopsy, be aware that the hospital may be the most expensive place you can have it done. Ask your physician for recommendations of where else you might have the procedure, and then call each facility to try to get an estimate of the costs you’d face.

Also, be wary of places that may look like independent doctor’s offices but are owned by a hospital. These practices also can tack hefty facility fees onto your bill.

If you get a bill that seems inflated, call your hospital and insurer and try to negotiate it down.

Bill of the Month is a crowdsourced investigation by Kaiser Health News and NPR that dissects and explains medical bills. Do you have an interesting medical bill you want to share with us? Tell us about it!

by Cara Anthony, a Kaiser Health News Midwest correspondent | Jul 10, 2019 | Faith & Work |

SHILOH, Ill. — After a health insurance change forced Bernard Macon to cut ties with his black doctor, he struggled to find another African American physician online. Then, he realized two health advocates were hiding in plain sight.

At a nearby drugstore here in the suburbs outside of St. Louis, a pair of pharmacists became the unexpected allies of Macon and his wife, Brandy. Much like the Macons, the pharmacists were energetic young parents who were married — and unapologetically black.

Vincent and Lekeisha Williams, owners of LV Health and Wellness Pharmacy, didn’t hesitate to help when Brandy had a hard time getting the medicine she needed before and after sinus surgery last year. The Williamses made calls when Brandy, a physician assistant who has worked in the medical field for 15 years, didn’t feel heard by her doctor’s office.

“They completely went above and beyond,” said Bernard Macon, 36, a computer programmer and father of two. “They turned what could have been a bad experience into a good experience.”

Now more than ever, the Macons are betting on black medical professionals to give their family better care. The Macon children see a black pediatrician. A black dentist takes care of their teeth. Brandy Macon relies on a black gynecologist. And now the two black pharmacists fill the gap for Bernard Macon while he searches for a primary care doctor in his network, giving him trusted confidants that chain pharmacies likely wouldn’t.

Black Americans continue to face persistent health care disparities. Compared with their white counterparts, black men and women are more likely to die of heart disease, stroke, cancer, asthma, influenza, pneumonia, diabetes and AIDS, according to the Office of Minority Health.

But medical providers who give patients culturally competent care — the act of acknowledging a patient’s heritage, beliefs and values during treatment — often see improved patient outcomes, according to multiple studies. Part of it is trust and understanding, and part of it can be more nuanced knowledge of the medical conditions that may be more prevalent in those populations.

For patients, finding a way to identify with their pharmacist can pay off big time. Cutting pills in half, skipping doses or not taking medication altogether can be damaging to one’s health — even deadly. And many patients see their pharmacists monthly, far more often than annual visits to their medical doctors, creating more opportunities for supportive care.

That’s why some black pharmacists are finding ways to connect with customers in and outside of their stores. Inspirational music, counseling, accessibility and transparency have turned some minority-owned pharmacies into hubs for culturally competent care.

“We understand the community because we are a part of the community,” Lekeisha Williams said. “We are visible in our area doing outreach, attending events and promoting health and wellness.”

To be sure, such care is not just relevant to African Americans. But mistrust of the medical profession is especially a hurdle to overcome when treating black Americans.

Many are still shaken by the history of Henrietta Lacks, whose cells were used in research worldwide without her family’s knowledge; the Tuskegee Project, which failed to treat black men with syphilis; and other projects that used African Americans unethically for research.

“They completely went above and beyond,” says Macon (center) of Vincent and Lekeisha Williams, owners of LV Health and Wellness Pharmacy.

Filling More Than Prescriptions

At black-owned Premier Pharmacy and Wellness Center near Grier Heights, a historically black neighborhood in Charlotte, N.C., the playlist is almost as important as the acute care clinic attached to the drugstore. Owner Martez Prince watches his customers shimmy down the aisles as they make their way through the store listening to Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Kirk Franklin, Whitney Houston and other black artists.

Prince said the music helps him in his goal of making health care more accessible and providing medical advice patients can trust.

In rural Georgia, Teresa Mitchell, a black woman with 25 years of pharmacy experience, connects her customers with home health aides, shows them how to access insurance services online and even makes house calls. Her Total Care Pharmacy is the only health care provider in Baconton, where roughly half the town’s 900 residents are black.

“We do more than just dispense,” Mitchell said.

Iradean Bradley, 72, became a customer soon after Total Care Pharmacy opened in 2016. She struggled to pick up prescriptions before Mitchell came to town.

“It was so hectic because I didn’t have transportation of my own,” Bradley said. “It’s so convenient for us older people, who have to pay someone to go out of town and get our medicine.”

Lakesha M. Butler, president of the National Pharmaceutical Association, advocates for such culturally competent care through the professional organization representing minorities in the pharmacy industry and studies it in her academic work at the Edwardsville campus of Southern Illinois University. She also feels its impact directly, she said, when she sees patients at clinics two days a week in St. Charles, Mo., and East St. Louis, Ill.

“It’s just amazing to me when I’m practicing in a clinic setting and an African American patient sees me,” Butler said. “It’s a pure joy that comes over their face, a sigh of relief. It’s like ‘OK, I’m glad that you’re here because I can be honest with you and I know you will be honest with me.’”

She often finds herself educating her black patients about diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and other common conditions.

“Unfortunately, there’s still a lack of knowledge in those areas,” Butler said. “That’s why those conditions can be so prevalent.”

Independent black-owned pharmacies fill a void for African American patients looking for care that’s sensitive to their heritage, beliefs and values. For Macon, LV Health and Wellness Pharmacy provides some of that vital support.

Avoiding Medical Microaggressions

For Macon, his experiences with medical professionals of backgrounds different from his own left him repeatedly disappointed and hesitant to open up.

After his wife had a miscarriage, Macon said, the couple didn’t receive the compassion they longed for while grieving the loss. A few years later, a bad experience with their children’s pediatrician when their oldest child had a painful ear infection sparked a move to a different provider.

“My daughter needed attention right away, but we couldn’t get through to anybody,” Macon recalled. “That’s when my wife said, ‘We aren’t doing this anymore!’”

Today, Macon’s idea of good health care isn’t colorblind. If a doctor can’t provide empathetic and expert treatment, he’s ready to move, even if a replacement is hard to find.

Kimberly Wilson, 31, will soon launch an app for consumers like Macon who are seeking culturally competent care. Therapists, doulas, dentists, specialists and even pharmacists of color will be invited to list their services on HUED. Beta testing is expected to start this summer in New York City and Washington, D.C., and the app will be free for consumers.

“Black Americans are more conscious of their health from a lot of different perspectives,” Wilson said. “We’ve begun to put ourselves forward.”

But even after the introduction of HUED, such health care could be hard to find. While about 13% of the U.S. population is black, only about 6% of the country’s doctors and surgeons are black, according to Data USA. Black pharmacists make up about 7% of the professionals in their field, and, though the demand is high, black students accounted for about 9% of all students enrolled in pharmacy school in 2018.

For Macon, though, the Williamses’ LV Health and Wellness Pharmacy in Shiloh provides some of the support he has been seeking.

“I still remember the very first day I went there. It was almost like a barbershop feel,” Macon said, likening it to the community hubs where customers can chitchat about sports, family and faith while getting their hair cut. “I could relate to who was behind the counter.”