Americans are in a mental health crisis – especially African Americans. Can churches help?

Americans are in a mental health crisis – especially African Americans. Can churches help?

Centuries of systemic racism and everyday discrimination in the U.S. have left a major mental health burden on African American communities, and the past few years have dealt especially heavy blows.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that Black Americans are twice as likely to die of COVID-19, compared with white Americans. Their communities have also been hit disproportionately by job losses, food insecurity and homelessness as a result of the pandemic.

Meanwhile, racial injustice and high-profile police killings of Black men have amplified stress. During the summer of 2020, amid both the pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests, a CDC survey found that 15% of Black respondents had “seriously considered suicide in the past 30 days,” compared with 8% of white respondents.

For a variety of reasons, many African Americans face barriers to mental health care. But as a sociologist who focuses on community-based organizations, I find that strengthening relationships between churches and mental health providers can be one way to increase access to needed services. In research with my collaborators Eunice Wong and Kathryn Derose, I analyzed data on the prevalence of mental health care provision among religious congregations and found that many African American congregations offer such programs.

Need versus access

Roughly 1 in 5 Americans experience mental illness in a given year. Yet fewer than half of adults with a mental health condition receive mental health services.

African Americans utilize mental health services at about one-half the rate of white Americans. In part, this underuse may stem from African Americans’ often fraught relationship with medical establishments in the U.S., given their histories of racial bias and malpractice against people of color. Part of the reason may also derive from stigma among some African Americans perceiving mental illness and seeking help as signs of weakness. Treatment “deserts” where mental health providers are scarce may also be a factor.

Care at church

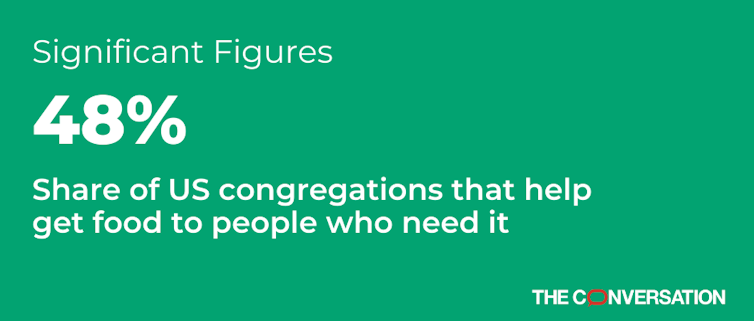

One often overlooked resource for mental health care, however, are churches. For the past decade, the National Congregations Study has documented the prevalence of mental health care provision among places of worship in the U.S. Based on data from the NCS’ 2018 survey, 26% of congregations provide mental health programming, and 37% of people who attend religious services attend one of these congregations. Such programming can include support groups, meetings and classes focused on addressing mental health concerns.

Previously, my co-researchers and I analyzed 2012 NCS data to better understand mental health resources within religious congregations. One of our goals was to identify factors that contribute to a congregation offering mental health care. These factors include having more members, employing staff for social service programs and providing health-focused programs. Other significant predictors include conducting community needs assessments, hosting speakers from social service organizations and being located in a predominantly African American community.

Based on the new 2018 survey, 45% percent of African American congregations offer some form of mental health service and nearly half of all African American churchgoers attend a congregation with such programs. These rates show an increase since 2012, and are roughly 50% greater than those among predominantly white congregations.

This research supports longstanding observations about African American congregations as critical sources of spiritual, emotional and social support for their communities. Many religious people see their spiritual health and mental health as intertwined, and research indicates that spiritual practices, such as prayer and meditation, can also support mental health.

Strengthening support

Our research suggests that building collaborations between African American congregations and the mental health sector is a promising strategy to increase access to needed services. Given that 61% of African Americans say they attend worship services at least a few times a year, congregations may provide an accessible resource.

At times, pairing religion and mental health may prove harmful. Some congregations see mental health problems as a product of personal sin, for example, and stigmatize people suffering from mental illness.

[This week in religion, a global roundup each Thursday. Sign up.]

But congregations can also be helpful environments. When clinical treatment is supplemented with social support, the likelihood of successful outcomes is greater, and houses of worship often provide built-in social networks. People participating in a congregation-led grief recovery group, for example, can be involved in the congregation beyond their weekly meeting. In addition, some mental health professionals provide pro bono services for congregation-based programs.

Social worker Victor Armstrong, the director of North Carolina’s Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities and Substance Abuse Services, asserts that African American faith leaders can play a “pivotal role” in mental wellness. He suggests shifting language to focus on “wellness” rather than “illness” in order to decrease stigma, among other recommendations.

Greater collaboration between congregations and mental health providers could help stem the growing mental health crisis, particularly within African American communities.![]()

Brad R. Fulton, Associate Professor, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.