The choir from Detroit’s Perfecting Church performs a rendition of “America the Beautiful” ahead of the #DemDebate. Watch CNN: http://CNN.it/go

Follow live updates: https://cnn.it/2SSNUK5

Gospel artist Donnie McClurkin. Photo by Christian Lantry

Two decades ago, gospel singer Donnie McClurkin stepped on a London stage to record his second album.

Now, he’s returning to the United Kingdom for 20th-anniversary concerts on Oct. 18 and 19 to reprise the music of his “Live in London and More” CD that featured songs like “That’s What I Believe” and “We Fall Down.”

The Grammy-winning pastor of Perfecting Faith Church, a Pentecostal congregation in Freeport, N.Y., says he latched onto the popularity of black gospel music that existed overseas long before his 1999 concert.

“People like Andrae Crouch and Edwin Hawkins and the like, they made the music global so it was all a byproduct of the global impact that American gospel had,” he said.

McClurkin, who will turn 60 on Nov. 9 and celebrate with a gospel-star-studded celebration a week later in Jamaica, N.Y., also hosts “The Donnie McClurkin Show.” He features a mixture of new and classic gospel music, interviews and inspirational messages that airs online and in some 60 markets from the U.S. to the United Kingdom to Africa.

He talked to Religion News Service about how Oprah Winfrey boosted his career, the status of his relationship with gospel artist Nicole C. Mullen and how retirement is a ways off.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Donnie McClurkin presents an in memoriam tribute to Andrae Crouch at the BET Awards at the Microsoft Theater on June 28, 2015, in Los Angeles. (Photo by Chris Pizzello/Invision/AP)

I decided to go to London, which was considered unusual by the record company itself, because of my mentor, the late great Andrae Crouch. He did a musical concert in 1978 in London. That became a landmark. And I always wanted to go to London from the time I knew where England was. And that was my prime opportunity because they gave me a blank check and said you just do an album however you want to do it.

I was nominal, I was at B-level at best — and Oprah Winfrey got wind of the (1996) CD. She put me on her television show and held up the CD and said, “This is my favorite singer. This is my favorite project.” And we went from 30,000 to 300,000 in a month and then finally went platinum. Then there’s President George W. Bush and President Bill Clinton and those kinds of things happened and made it something larger than life.

They brought me to their convention, to sing at the (Democratic National Convention), to sing at the (Republican National Convention), opened it up to thousands of people in a room, millions of people around the world and that’s where a lot of attention started coming in.

I’m over in London just about once a year in concert. Since “Live in London” 20 years ago, I’ve got a very strong base over there, very strong community in England and in Europe period, from Italy to Germany to Holland to the U.K.

I sing less in the U.S. than I do in Africa and Europe.

In the GMA, I see a lot of inclusion. For a long time, it was very, very segregated. GMA was for the CCM (contemporary Christian music) and the white gospel singers. And in the last three or four years I’ve seen such an inclusion, integration of black gospel artists along with the contemporary white gospel artists.

Gospel artist and pastor Donnie McClurkin. Photo by Christian Lantry

The GMA as a whole, as an organization, not just the awards show but the organization itself. It’s grown and it’s matured and it’s let go of a lot of the institutionalized bias and has become inclusive of our music form, which is — and I probably will get in trouble — but our black music form is the strongest music form in gospel music. It’s what people gravitate to around the world, so “Oh Happy Day,” the whole of our repertoire. It’s been the most marketable. It’s been the most commercial. It’s been the most prominent. It’s apropos that at this point in time we are now sitting with equality at that table as well.

You have described yourself as a victim of childhood sex abuse and when you claimed you had overcome homosexuality, that prompted opposition from gay rights groups. How do you describe yourself now and are you involved in either so-called ex-gay ministries or initiatives that affirm LGBTQ people?

First of all, I’ve never been a part of any ex-gay anything. My past is just that: past. P-a-s-t. It’s gone. Who do I consider myself to be now? I consider myself to be Donnie. A wonderful, old man now — I never thought I’d be calling myself that — who is peaking 60 years old come next month and who has overcome a lot more than sexuality. But that’s been a great part of my life. It is something that I celebrate. I am a part of a church that embraces everybody. I am a pastor of a church that has hetero and homo in it as well. I believe in the love of God that reaches out to everybody, the love of God that is unconditional, the love of God that is not based on ethnicity, it’s not based on denomination, it’s not based on classification.

I believe in the transformative love that only comes through God and that’s what I preach. That’s what I live. That’s what I teach. I have a lot of LGBTQ friends in and out of the church. I’ve got a lot of people that appreciate what I’ve been through and they don’t judge me and I don’t judge them and that’s the way that this is supposed to work. It’s supposed to be a love that is real and genuine, that can accept people for who they are, even if you don’t agree with them.

Gospel artist and pastor Donnie McClurkin. Photo by Christian Lantry

We are great friends. We are very, very great friends.

In another 10 years (laughs) or maybe 20 years. Singing is something that’s marginal for me now. I do it when I want to do it. I do it when it’s convenient to do it, and I do it when it has a purpose, if it’s going to bring somebody to a greater understanding of who Christ is. I don’t do it just for the entertainment aspect of it any longer. I am selective in what I do. Aretha Franklin told me years ago, “There’s a time when you got to sing and there’s a time when you sing when you want to.” And that makes sense to me now. I’m at a time now I sing when I want to.

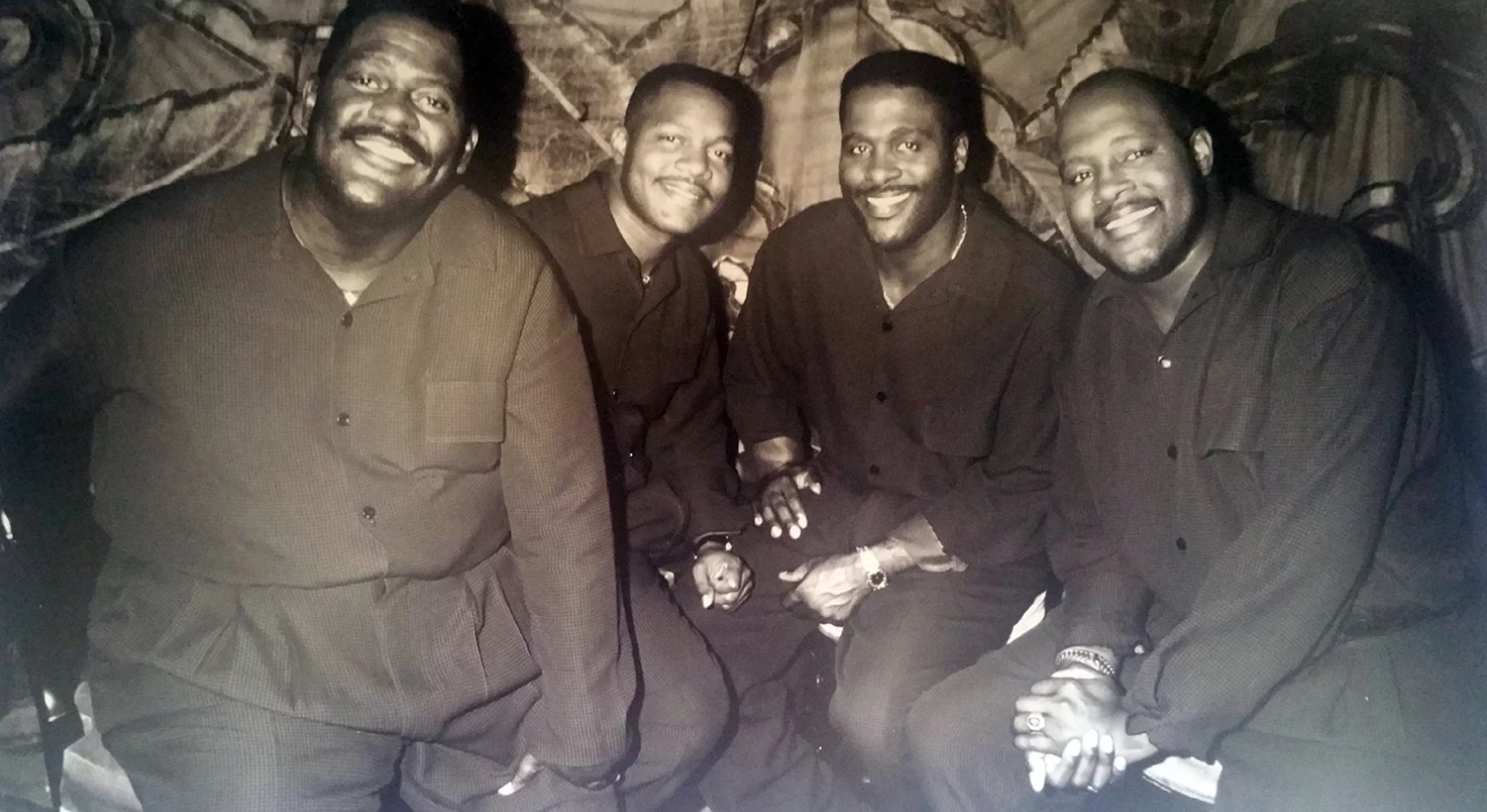

The Winans group in 1995 included Ronald, from left, Michael, Carvin and Marvin. Photo by Jeffrey Mayer

Thirty years ago, Pastor Marvin Winans was singing with three of his brothers in the gospel group The Winans and touring with his musical play, “Don’t Get God Started,” after its Broadway run.

He also started a church. Beginning with just eight members meeting in the basement of his house in the Detroit suburb of Birmingham, Winans became the pastor of Perfecting Church, a Pentecostal congregation that soon became a place where young adults could develop their spiritual lives.

“The church just begin to grow because we would go into the Dairy Queen, wherever we could find young people, and tell them they need to come to church,” he recalled in an interview Tuesday (Oct. 1) with Religion News Service. “And when they came, they stayed and we grew very fast.”

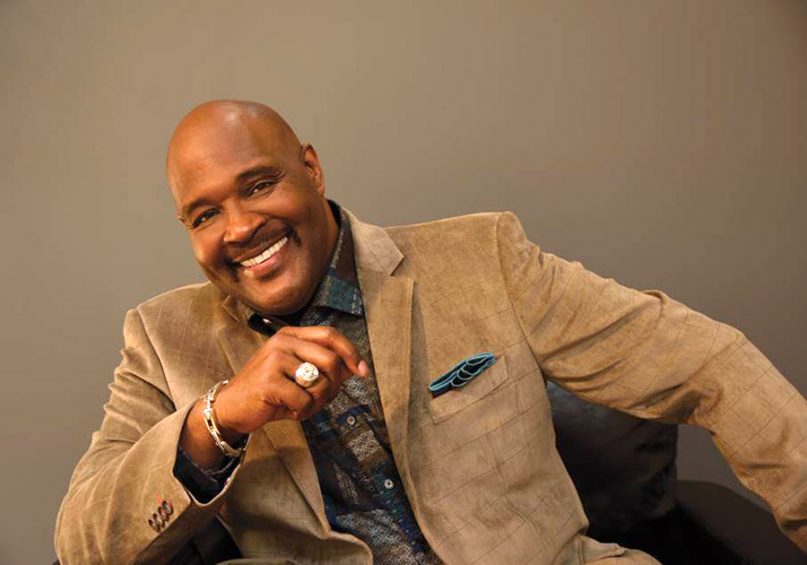

Pastor Marvin Winans. Photo courtesy of GBP Studio 2

Fast forward three decades and Winans is marking the anniversary of his church, now with 1,800 members in the Motor City, while remaining committed to helping his community through the schools and ministries he has started to help train youth and give women a safe place to live.

For Perfecting Church’s Oct. 11 anniversary gala, Winans, 61, has invited social justice activist Bryan Stevenson to speak. BeBe and CeCe Winans, his singing siblings, also are slated to perform.

To be a Grammy-winning pastor, however, is to live a double life: Though officially retired from singing, Winans still agrees to some requests. Earlier this year, he was featured at the Super Bowl Gospel Celebration and with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra’s “Gospel Goes Classical” concert.

“What stands out to me about Marvin Winans musically is just the beauty and seemingly effortless vocal technique,” said Bil Carpenter, author of “Uncloudy Days: The Gospel Music Encyclopedia,” who said the Detroit senior pastor was the “backbone” of The Winans.

“I have been in events or services where he wasn’t on the program. He was just there. Someone handed him the mic. It was as if he had rehearsed. He picks up on other people’s songs and sings them better than they sing them.”

Winans’ skills as an arranger and conductor have also been on display recently: At the start of the July Democratic presidential candidate debate at Detroit’s Fox Theatre, he directed Perfecting Church singers in his new rendition that combined women singing “America the Beautiful” and men singing “Amazing Grace.”

The choir from Detroit’s Perfecting Church performs a rendition of “America the Beautiful” ahead of the #DemDebate. Watch CNN: http://CNN.it/go

Follow live updates: https://cnn.it/2SSNUK5

“All I can tell you is, music is what I do,” he said, describing how, while sitting at the piano and going over the voice parts during a rehearsal, a thought came to him: “Wow, this sounds similarly like ‘Amazing Grace’ and we just split it and had that happen.”

Renee Compton, a choir director at Perfecting Church, was among the singers who watched Winans’ creative process in person and rehearsed several times for the two-and-half-minute performance.

“It’s very intense, but it’s also very good ’cause you actually sit there and you learn and you just see the creative genius of it,” said Compton, who helped found Perfecting Church while in her 20s. “The gift that he has to do that is just absolutely incredible, that he’s able to just put all of that together.”

RELATED: Marvin Winans will add soul to Whitney Houston’s funeral

One of 10 children of Delores “Mom” Winans and David “Pop” Winans, Marvin Winans grew up in a household where gospel music was the only genre allowed to be sung or played. Attendance at his great-grandfather’s Church of God in Christ was a regular practice. He served as a young minister at Shalom Temple, a Holiness church in Detroit and continued his connection with the Pentecostal/Holiness tradition when he started his predominantly black congregation.

Cindy Flowers, the general manager of Perfecting Church, said she became the church’s first employee in July 1989.

“We probably had about 13, 15 members, and I’m thinking, ‘Why do we need staff?’” said Flowers, who also was one of the eight founding members. “But Pastor Winans just has always had a much, much, much bigger vision.”

As the church developed, it moved from Winans’ basement to a hotel to rented church buildings, often meeting in the afternoons after their landlords’ services. Meanwhile, Winans expanded the scope of his work in Detroit. He founded the Winans Academy of Performing Arts in 1997 and developed the Rutherford Winans Academy in 2012. The two public charter schools currently have a total enrollment of more than 600 students, Winans said.

Pastor Marvin Winans. Photo courtesy of GBP Studio 2

He also started the Amelia Agnes Transitional Home for Women in an upscale Detroit suburb after a woman in his church told Winans she was living with a man who was not her husband but was helping care for her children.

“We don’t believe in folk shacking and living with folk that are not their husband legally or wife legally,” said Winans. “And that struck me, and the Holy Spirit said, ‘You cannot only tell them what to do. You have to offer an alternative.’”

Since the transitional home opened in 2001, it has housed about 50 single women and mothers, some who have been referred from homeless shelters and some who have been in abusive situations. It is named after Winans’ mother and the mother of his ex-wife, Vickie Winans, who had a total of 22 children.

The home’s clients occupy one of five family suites while they pursue employment and education opportunities and gain parenting and financial tips, said VeronCia Compton, executive director of the Perfecting Community Development Corporation, which includes the home among its programs. Some have completed nursing programs and master’s degrees.

In 2017, Winans opened Perfecting Church Toledo, which has more than 150 members at its Ohio location. On Sundays and some weekdays, he travels the hour-and-a-half drive between Toledo and Detroit to preach and meet with members.

Though the Detroit church listed 4,500 members on its website as of this week, Flowers said a recent “reregistration” of its members indicated about 1,800.

“Church is a little different during these times: People say, ‘You’re still my pastor’ but they’re inactive, they’ve moved. They’re out of town,” Winans said, when asked about the recount. “What we want to do is make sure we’re ministering to those who are not just in word saying, ‘I’m a member of the church,’ but are active in the church.”

One former member sued Winans in 2018 after accusing him of unfair labor practices.

Lakaiya Harris, a former housekeeping employee, claimed, among other things, that Winans required her as a member of the church to tithe on her gross earnings. Her suit alleges that when she refused, Winans fired her.

“That couldn’t be further from the truth,” Winans said when asked about Harris’ claims. “That’s being taken up in the court. I’ll leave it at that.”

Winans said the anniversary gala will help raise money for the transitional home as well as for a new edifice that has long been under construction on a 20-acre campus in Detroit. After it opens, he hopes to be consecrated as bishop of Perfecting Fellowship International, a network including more than a dozen churches in the U.S., the U.K. and South Africa.

He said it’s fitting to have Stevenson, a lawyer who works to exonerate wrongly convicted prisoners, as the speaker for his church’s anniversary. Winans said he has visited the museum and lynching memorial Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative opened in Montgomery, Alabama, last year.

“We want to stand on the side of justice equality,” Winans said. “We want to stand against the inequalities of our people. And that doesn’t make me a civil rights preacher. It just makes me a preacher that understands the importance of civil rights.”

An Episcopal seminary in Virginia has announced plans to create a $1.7 million endowment fund whose proceeds will support reparations for the school’s ties to slavery.

Virginia Theological Seminary said that enslaved persons worked on its campus and the school “participated in segregation” after the end of slavery.

“This is a start,” said the Very Rev. Ian S. Markham, president of the Alexandria-based seminary, in the statement. “As we seek to mark (the) Seminary’s milestone of 200 years, we do so conscious that our past is a mixture of sin as well as grace. This is the Seminary recognizing that along with repentance for past sins, there is also a need for action.”

A spokesman for the seminary said officials know of three buildings on its campus that were built with slave labor, including Aspinwall Hall, where the dean’s and admissions offices are located.

“We do want to honor those who worked in this place and we want to provide financial resources for their descendants,” said Curtis Prather, the seminary’s director of communications. “The Office of Multicultural Ministries will take the lead in the exhaustive research that will need to take place.”

Aspinwall Hall at Virginia Theological Seminary was one of three buildings on campus built with slave labor. Photo by John W. Cross/Creative Commons

The seminary, which was founded in 1823 but admitted its first African American student in 1951, raised the funds for the endowment with a capital campaign. School officials estimate that they will spend $70,000 annually from accumulated interest on reparations.

The decision comes as other institutions of higher learning, some with ties to religion, have mulled whether to offer forms of reparations or not.

In 2017, Georgetown University apologized for its involvement in the 1838 sale of more than 270 enslaved persons that kept the Catholic-run school from bankruptcy. The school renamed two buildings that once honored former university presidents who were priests and supporters of the slave trade. A year earlier, Georgetown announced that it would give preferential status in the admissions process to descendants of the enslaved people who had been owned by Maryland Jesuits.

Jennifer Oast, author of “Institutional Slavery: Slaveholding Churches, Schools, Colleges, and Businesses in Virginia, 1680-1860,” said the seminary’s “momentous announcement” is more noteworthy than the nonbinding vote by Georgetown students in the spring to add a student fee whose proceeds would benefit the descendants of the slaves sold more than a century and a half ago.

Georgetown spokesperson Meghan Dubyak said the school’s board of directors will not have an “up or down” vote on the student referendum but “will engage thoughtfully and with the most careful consideration of the issues” raised by it.

Crowds of slave descendants and Georgetown University students and staffers gather for a dedication ceremony of two buildings at the school that were renamed, one in honor of a slave sold by Maryland Jesuits, and another for a free black woman educator, on April 18, 2017. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“To my knowledge, this is the most substantial direct financial reparations effort by a university,” said Oast, chair of the history department at Bloomsburg University in Pennsylvania. “What makes this action by VTS more significant is that it has been undertaken by the university itself, and is fully funded.”

Quardricos Driskell, who teaches religion and politics at George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management, agreed.

“VTS would by definition be the first to have a fund — a University-established led form of reparations,” Driskell, pastor of Beulah Baptist Church, located about three miles from the seminary, told Religion News Service in an email message.

Other institutions have chosen to recognize their connections to slavery without making monetary reparations. Last year, Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, a flagship institution of the Southern Baptist Convention in Louisville, Kentucky, released a report about its founders condoning slavery and owning slaves, but six months later denied a request from an interracial ministers coalition for financial support for a nearby black college.

Virginia Theological Seminary currently has an enrollment of about 200 master’s and doctoral level students.

The school intends to determine with stakeholders how the income from the endowment fund will be distributed. It said some of it will be allocated to descendants of enslaved persons who worked at the seminary and to assist the work of African American alumni, especially those involved with historic black churches. It also plans to encourage African American clergy in the Episcopal Church and support programs that promote inclusion and justice.

“Though no amount of money could ever truly compensate for slavery, the commitment of these financial resources means that the institution’s attitude of repentance is being supported by actions of repentance that can have a significant impact both on the recipients of the funds, as well as on those at VTS,” said the Rev. Joseph Thompson, director of the seminary’s Office of Multicultural Ministries, in a statement.

“It opens up a moment for us to reflect long and hard on what it will take for our society and institutions to redress slavery and its consequences with integrity and credibility.”

Video Courtesy of Biography

Months before the annual observance of the bombing that rocked a congregation, a community and the nation, 16th Street Baptist Church has been getting ready.

Renovations were taking place in June: fresh paint and new technology for the classroom spaces in the basement. Just as at worship services, Sunday school attendance ebbs and flows each week, depending on the number of longtime members and curious tourists. This Sunday (Sept. 15), which marks the 56th anniversary of the attack that killed four young girls, the church hopes to unveil the refurbished space where visitors can watch videos about kindness, caring for all humans no matter their race, and the civil rights history of the church and its community.

“After you leave this place, we don’t just want you to experience history,” the Rev. Arthur Price Jr. said in a June interview at his church. “We call the four girls ‘angels of change’ and our hope is that people will leave inspired, become agents of change as a result of what happened here.”

The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church sanctuary, which features images of the four girls who were killed in 1963, in June 2019. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

“We’re adding more content about not just what happened in 1963 but how the church was organized and the tension that was going on in the city during that time,” Price said in a subsequent interview about the church that was at the forefront of the civil rights movement before and after the bombing.

The pastor was busy this week preparing for his church’s “memorial observance” that is expected to feature special guests including a prominent U.S. chaplain, the pastor of another church that was attacked and a presidential candidate.

Lt. Col. Ruth Segres, an Air Force chaplain at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph in Texas, will be leading the Sunday school lesson.

“That Sunday school lesson that was taught that Sunday (of the bombing) was ‘The love that forgives’ and she will teach a lesson surrounding that theme,” Price said of Segres, who is in charge of recruiting Air Force chaplains.

Just before the church bells are set to toll at 10:22 a.m. — the moment on Sept. 15, 1963, that the dynamite set by members of the Ku Klux Klan went off — former Vice President Joe Biden “will give a reflection about the day,” the pastor said.

After a wreath laying, the Sunday service will start, with the Rev. Eric S.C. Manning, pastor of Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church of Charleston, South Carolina, serving as the guest preacher.

“I think we have a symbiotic relationship, considering the two churches experienced acts of violence within their place of worship,” said Price of the AME church where nine worshippers were killed by a white supremacist during a 2015 weekday Bible study.

“This is a way that we can come together in solidarity and preach the message of Jesus Christ and how he teaches us to stand tall and not to fear in the face of adversity.”

Flowers are placed on a marker remembering the four girls who were killed in a bombing on Sept. 15, 1963, at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in June 2019. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

The observance recalls the deaths of Denise McNair, Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Morris, who is also known as Cynthia Wesley. They were preparing for the church’s Youth Day when they died. As a poem by Camille T. Dungy in a recent special edition of The New York Times Magazine noted, had they lived, one of the girls would have been 67 and the other three 70 this year.

“We’ll toll the bells for the four girls and two more times for the two boys who lost their lives that day,” Price said, referring to two black male teenagers who were shot to death in Birmingham in the hours after the bombing.

The church, which dates to 1873, reopened in June 1964. Price said the basement was renovated the following year and has since featured fellowship gatherings, men’s breakfasts and Bible studies.

Convictions in the killings did not occur for decades.

A memorial at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, where four girls were killed in a bombing on Sept. 15, 1963. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

A “Justice Delayed” exhibit at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute across the street from the church noted that Robert Chambliss, Thomas “Tommy” Blanton Jr. and Bobby Frank Cherry were identified as potential suspects as the FBI initially investigated the blast. But it wasn’t until much later, after subsequent probes, that they were tried and received sentences of life imprisonment. Cherry was the last to be convicted, in 2002.

Beyond the annual Sept. 15 observance, at other times there are reminders of the tragedy, some marked with grief, others with hope.

In May, Price officiated at the funeral of Chris McNair, father of one of the four girls killed in 1963, and a former Alabama state legislator. And just last week, Price welcomed to the church a government delegation from Wales, including its minister for education, Kirsty Williams.

“She was proud to see the Wales window that was given by the people of Wales in 1965 to the church because the people of Wales wanted to make a statement of solidarity with the movement,” he said of the Sept. 5 visit.

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, right, is across the street from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, left. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

An adaptation of the window, which features the image of a black crucified Christ, is now part of the church’s logo.

Price said the visitors from Wales were heeding the message he hopes his church inspires even before the church launches the new videos about kindness across racial lines.

“That’s one of the things that the Welsh government did,” he said. “They presented us with a plate with a black hand and a white hand extended to each other, dealing with even though we’re different, we’re not deficient, and that we ought to be working together so that we make sure that what happened here 56 years ago never happens again.”

“Dear Church” cover and author Rev. Lenny Duncan. Photo courtesy of Fortress Press

The Rev. Lenny Duncan is not your typical Evangelical Lutheran Church in America minister.

Duncan is the black pastor of a mostly Afro-Caribbean congregation in one of the nation’s least diverse denominations. He recently decided to challenge that denomination — the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America — in a new book titled “Dear Church: A Love Letter from a Black Preacher to the Whitest Denomination in the U.S.”

At Jehu’s Table church in Brooklyn, New York, Duncan proclaims his gratitude during Communion for African American role models ranging from transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson to Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X to civil rights minister Martin Luther King Jr.

Duncan, 41, talked to Religion News Service about why he is confronting his 94% white denomination, how churches can overcome the notion that they are dying, and what he has in common with Dylann Roof, a Lutheran man convicted of killing nine people at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I grew up in an abusive home. And one of the first times I ever tried to defend my mom, I was about five years old and I stood over her body and I tried to block the blows that my father was raining down on her. That’s what “Dear Church” feels like for me. It’s an attempt of self-defense of the church that I love.

When we’re talking about dismantling the structures of systemic racism, there’s repentance and eventually there’s reconciliation, but there has to be reparations in the middle. There have to be constructive, quantifiable actions that show that you’ve turned around. So, while I think it’s a good start, I certainly don’t think the job’s anywhere near done.

It is time for all straight white males in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America to remove their names from ballots for bishop. It’s the same thing when we come to some of the positions that we see in our churchwide organization — to just self-select their way out. This comes from my experience at seminary and other places. As someone who shows up as a cis male, if I’m quiet long enough typically a female or femme in the room will say the same thing I was gonna say much more succinctly and probably more intelligently than I would.

Yeah. Most of the time whenever a person of color voice is added to the curriculum — even if we talk about James Cone; lots of times professors suggested I read Dr. Cone’s work — but it’s always the extra book or the recommended reading.

It wasn’t required reading.

In my book, I don’t rely on the good nature of white folks. What my work offers to them is that the American white Protestant church is obsessed with legacy. If you want your church to survive, if you want your denomination to be relevant in the 21st century, if you actually want a viable Lutheran legacy in the American context, then you’ll take these suggestions. Because my blood hasn’t ever encouraged them. The blood of Trayvon Martin has never encouraged them. The blood of Michael Brown has never encouraged them. The blood of Eric Garner has never encouraged them to change. So now what I’m offering is the death of their own church because this is the direction that the American context is headed, and I’m just trying to point towards that.

The Rev. Lenny Duncan. Courtesy photo

The reality is that Dylann was only a few decisions away from being me or I was only a few decisions away from being Dylann. Neither of us were nurtured and supported when we were younger, and it’s really by the grace of God that I didn’t end up in a similar situation as Dylann. For me, the struggle has been not to make Dylann Roof into a monster or into a demon or into a boogeyman but as someone who could be sitting in the pews of any ELCA church right now and is just waiting for a good word to push that person in the right direction or a lack thereof, because power abhors a vacuum, and then be pushed in the same direction Dylann was.

I try to parallel our histories in a way that makes it more real for folks so that folks can see that this is important work that should be done now, particularly in areas where there isn’t a lot of diversity, to make sure something like Charleston never happens again.

What’s the color for Easter? White. How is Christ depicted in most of our liturgical art that’s inside our sanctuaries? White. This is particularly a problem in the American context because whiteness and white supremacy is so embedded in our culture that we start relating white as good and dark as bad.

You see the story in Advent, this whole idea of darkness to light.

How we tell the story is just as important as the story we’re telling. The tools that we use and the symbols that we use have long-term, often detrimental, effects to the children sitting in our pews. When I was in seminary someone said to me, “I’m not going to let a blip in Christian history ruin white robes for me.” And what I replied to them is, “Your people didn’t get their a– kicked by that blip in Christian history. So it’s easy for you to get past it.”

I think more and more people are starting to realize that queer Christians have been a part of the Christian experience since the very beginning. Often, we will hear people talk about (the biblical story of) the Ethiopian eunuch. The truth is, queer folks are in every church and every denomination and there’s no avoiding it. So the real issue is, is your God big enough, is your Jesus big enough? Is your church big enough to open up the gates of grace wider for other people?

I think we need to rethink church and we need to rethink the way that we count membership. I might have, like, 40, 50 people in my church on a Sunday. But there’s 200 people who are engaged in our community in various ways.

For me it’s about who is encountering Jesus and having their life transformed and how a whole community is being transformed by a Jesus who is trying to liberate them from their circumstances, either spiritually, physically, economically, socially. A lot of times, even at 4,000 people inside a building, that doesn’t mean any of that s— is happening.