The Brown v. Board of Education case didn’t start how you think it did

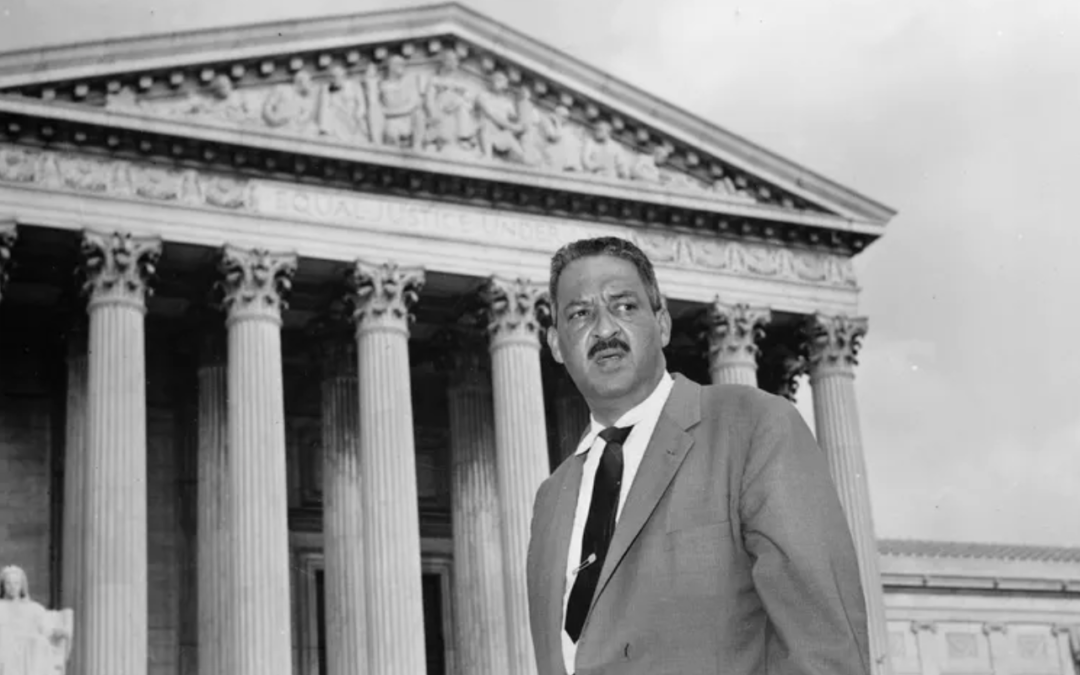

Thurgood Marshall outside the Supreme Court in Washington in 1958. Marshall, the head of the NAACP’s legal arm who argued part of the case, went on to become the Supreme Court’s first African-American justice.AP

As the nation celebrates the 65th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, the case is often recalled as one that “forever changed the course of American history.”

But the story behind the historic Supreme Court case, as I plan to show in my forthcoming book, “Blacks Against Brown: The Black Anti-Integration Movement in Topeka, Kansas, 1941-1954,” is much more complex than the highly inaccurate but often-repeated tale about how the lawsuit began. The story that often gets told is that – as recounted in this news story – the case began with Oliver Brown, who tried to enroll his daughter, Linda, at the Sumner School, an all-white elementary school in Topeka near the Browns’ home. Or that Oliver Brown was a “determined father who took Linda Brown by the hand and made history.”

As my research shows, that tale is at odds with two great historical ironies of Brown v. Board. The first irony is that Oliver Brown was actually a reluctant participant in the Supreme Court case that would come to be named after him. In fact, Oliver Brown, a reserved man, had to be convinced to sign on to the lawsuit because he was a new pastor at church that did not want to get involved in Topeka NAACP’s desegregation lawsuit, according to various Topekans whose recollections are recorded in the Brown Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society.

The second irony is that, of the five local desegregation cases brought before the Supreme Court by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1953, Brown’s case – formally known as Oliver Brown et al., v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al. – ended up bringing widespread attention to a city where many blacks actually resisted school integration. That not-so-small detail has been overshadowed by the way the case is presented in history.

Black resistance to integration

While school desegregation may have symbolized racial progress for many blacks throughout the country, that simply was not the case in Topeka. In fact, most of the resistance to the NAACP’s school desegregation efforts in Topeka came from Topeka’s black citizens, not whites.

“I didn’t get anything from white folks,” Leola Brown Montgomery, wife of Oliver and mother of Linda, recalled. “I tell you here in Topeka, unlike the other places where they brought these cases we didn’t have any threats” from whites.

Prior to the Brown case, black Topekans had been embroiled in a decade-long conflict over segregated schools that began with a lawsuit involving Topeka’s junior high schools. When the Topeka School Board commissioned a poll to determine black support for integrated junior high schools in 1941, 65 percent of black parents with junior high school students indicated that they preferred all-black schools, according to school board minutes.

Separate but equal

Another wrinkle to the story is that the city’s four all-black elementary schools – Buchanan, McKinley, Monroe and Washington – had resources, facilities and curricula that were comparable to that of Topeka’s white schools. The Topeka school board actually adhered to the “separate-but-equal” standard established by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case.

Even Linda Brown recalled the all-black Monroe Elementary School that she attended as a “very nice facility, being very well-kept.”

“I remember the materials that we used being of good quality,” Linda Brown stated in a 1985 interview.

That made the Topeka lawsuit unique among the cases the NAACP Legal Defense Fund combined and argued before the Supreme Court in 1953. Black schoolchildren in Topeka did not experience overcrowded classrooms like those in Washington, D.C., nor were they subjected to dilapidated school buildings like those in Delaware or Virginia.

While black parents in Delaware and South Carolina petitioned their local school boards for bus service, the Topeka School Board voluntarily provided buses for black children. Topeka’s school buses became central to the local NAACP’s equal access complaint due to weather and travel conditions.

Quality education was “not the issue at that time,” Linda Brown recalled, “but it was the distance that I had to go to acquire that education.”

Another unique characteristic of Topeka public schools was that black students went to both all-black elementary and predominantly white junior high and high schools. This fact presented another challenge for the Topeka NAACP’s desegregation crusade. The transition from segregated elementary schools to integrated junior and senior high schools was a harsh and alienating one. Many black Topekans recalled the overt and covert racism of white teachers and administrators. “It wasn’t the grade schools that sunk me,” Richard Ridley, a black resident and Topeka High School alumnus who graduated in 1947, told interviewers for the Brown Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society. “It was the high school.”

Black teachers cherished

A primary reason that black Topekans fought the local NAACP’s desegregation efforts is because they appreciated black educators’ dedication to their students. Black residents who opposed school integration often spoke of the familial environment in all-black schools.

Linda Brown herself praised the teachers at her alma mater, Monroe Elementary, for having high expectations and setting “very good examples for their students.

Black teachers proved to be a formidable force against the local NAACP. “We have a situation here in Topeka in which the Negro Teachers are violently opposed to our efforts to integrate the public schools,” NAACP branch Secretary Lucinda Todd wrote in a letter to the national NAACP in 1953.

Black supporters of all-black schools used a number of overt and covert tactics to undermine NAACP members’ efforts. Those tactics included lobbying, networking, social ostracism, verbal threats, vandalism, sending harassing mail, making intimidating phone calls, the Brown Oral History Collection reveals.

But the national office of the NAACP never appreciated the unique challenges that its local chapter faced. The Topeka NAACP struggled to recruit plaintiffs, despite their door-to-door canvassing.

Fundraising was also a major problem. The group could not afford the legal services of their attorneys and raised only $100 of the $5,000 needed to bring the case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Unheralded legacy

History ultimately would not be on the side of the majority of Topeka’s black community. A small cohort of local NAACP members kept pushing for desegregation, even as they stood at odds with most black Topekans.

Linda Brown and her father may be remembered as the faces of Brown v. Board of Education. But without the resilience and resourcefulness of three local NAACP members – namely, Daniel Sawyer, McKinley Burnett and Lucinda Todd – there would have been no Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

The real story of Brown v. Board may not capture the public imagination like that of a 9-year-old girl who “brought a case that ended segregation in public schools in America.” Nevertheless, it is the truth behind the myth. And it deserves to be told.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story appeared in The Conversation on March 30, 2018.![]()

Charise Cheney, Associate Professsor of Ethnic Studies, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.