John Piper on Race and the Christian

A Discussion about Race and the Christian with Tim Keller, Anthony Bradley, and John Piper (Photo courtesy of Crossway Books)

The Rev. Dr. John Piper has, by his own count, written 30 books. His latest is Bloodlines: Race, Cross, and the Christian, a book that is rooted in Reformed theology and Piper’s personal story of growing up as a Southern racist who was redeemed by Christ and later transformed by the adoption of his African American daughter, Talitha. Piper says he will retire as pastor of Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in about a year, and will be replaced by another white pastor with a personal commitment to racial reconciliation. Piper is one of the first and the few white evangelical pastors to issue a public statement about the shooting death of Florida teen Trayvon Martin. He says revelations that Martin may not have been as wholesome a boy as initially portrayed are irrelevant to the case and the outcome could have been different if Zimmerman had been constrained by the gospel.

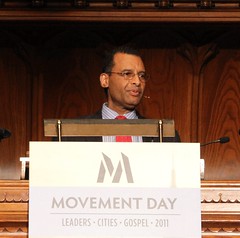

On Wednesday, March 28, Piper, Redeemer Presbyterian Church pastor, the Rev. Dr. Tim Keller, and The King’s College theologian Dr. Anthony Bradley participated in a vibrant discussion about Race and the Christian at the New York Society for Ethical Culture in New York City. UrbanFaith talked to Piper Thursday morning about the discussion, the book that inspired it, and his own journey toward racial harmony. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

UrbanFaith: What are your initial reflections about Wednesday night’s discussion about Race and the Christian?

John Piper: I come away from all events revolving around race with ambivalence. I’m never confident that I have said anything helpful. I generally come away from those things feeling like I learned another blind spot. I work with such an awareness of how little I see, so when Tim, in particular, was talking, I thought: I never thought of that. My next thought was: Okay, don’t be paralyzed by that. Don’t run away. Take that in. Learn. Build on that. Stand there. Take another step. Try to grow. In my younger day, I felt like quitting so many times after conversations. Now I put my feet on God and say, “Move forward.”

You communicate a lot of humility about your own failures and struggles in the area of racial reconciliation. Why have you been able to resist the temptation to give up?

One short answer would be that I adopted Talitha. That’s a real inadequate answer, but it’s a true answer, meaning that when we made the decision to adopt an eight-week old African American baby when I was 50 years old, I thought: Oh man, when she is 15, I’m going to be 65. What is it like for a 15-year-old girl to have a 65-year-old dad? What is it like for an African American girl to have a white 65-year-old dad? All those questions were tumbling around inside of me 16 years ago. My wife and I just looked at each other and said, “This is the right thing to do. This locks us in to the issue forever.” That’s why I can’t walk away. I signed on with blood. You can sign with ink or pencil and erase that, but when you sign with blood, you don’t erase that. And so, we’re in. There is a deeper reason. Biblically, socially, historically, my history, globally, it’s just too big to walk away from.

There are only two paragraphs in Bloodlines about your daughter. Can you tell us more about your experience of raising her?

We began to take race seriously 20 years ago maybe, where I’d preach on it every Martin Luther King weekend. Into that, we were heavy into the pro-life [cause]. I was getting arrested. I spent a night in jail. That’s how serious it was. The guy next to me in the cell, Rod Elofson, leaned over and said, “There’s probably a better way to do this.” His next step was to adopt two black kids who might have been aborted. So the two issues conjoined for me and they’ve been conjoined for 20 years with a pro-life sermon and a race sermon every February.

[Rod] lives across the street from me and he named a fund the MICAH Fund after his kids. [It’s an acronym for] Minority Infant Child Adoption Help, which means it raises money to help people pay for adoptions. This began to spread through our church and Phoebe Dawson (a black social worker from Georgia, who’s kind of the Underground Railroad to us) was bringing these kids up and my wife got to know her. My wife [Noël Piper] was 48 and I was 50. She got a phone call from Phoebe one day, and Phoebe said, “I have a little girl here. I think she’s yours.” You don’t say that to a 48-year-old woman that has four sons and no daughter, who always wanted a daughter. The dynamics here are just explosive emotionally.

We took long walks at the arboretum and talked and talked about the implications for our lives. We were done having kids. These kids were on their way out and we were going to have a chapter of freedom after the kids. We locked ourselves in for another 16- 20 years. (Of course, now we’ve got adult kids and we know you never stop parenting.) At eight weeks old, she came to us in her beautiful little white dress and there she’s been ever since.

There’s a distinction between [adopting an infant] and becoming acclimated to a person who is culturally black. Talitha is not. We’ve labored hard to make her aware, to have all the history, to connect her with friends, so there would be some link with African American culture. But, by-and-large, she is white inside. Everybody knows that. She talks white. She thinks white. She relates white. What that will mean long term for her, I don’t know. That’s just one of the huge issues. We have black folks in our church who think I’m stupid. One of my elders thinks trans-racial adoption is not a good idea. He’s tolerant, but he doesn’t think it’s a good idea, because he thinks it just deculturates [adopted children].

How do you deal with that criticism?

I say, “This girl had a mom who came to the clinic to get rid of her.” Phoebe is in the business of persuading women that that’s not a good idea, that there are better alternatives. We were the better alternative, and so I said to Talitha, “Culture and ethnicity has some value. Being in the image of God has infinitely more value. So, on balance, that she’s a human being and that she comes to know Jesus Christ and lives forever in the family of God is like a billion and that’s she’s black is 10.

continued on page 2