Can the religious right and left be more than a rubber stamp for their parties’ policies?

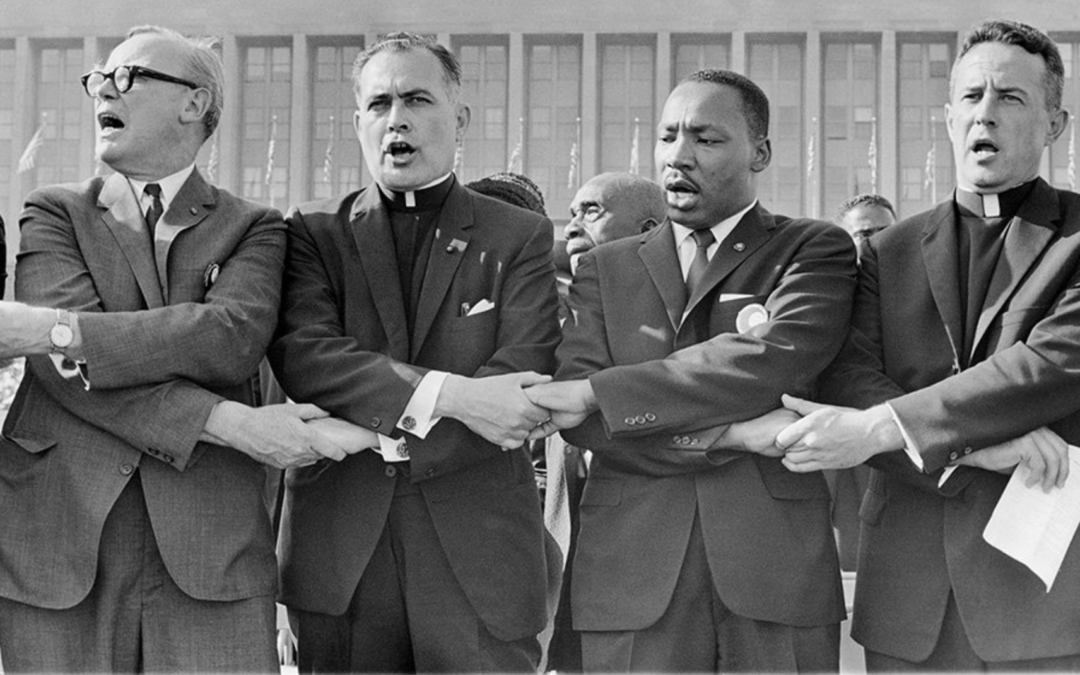

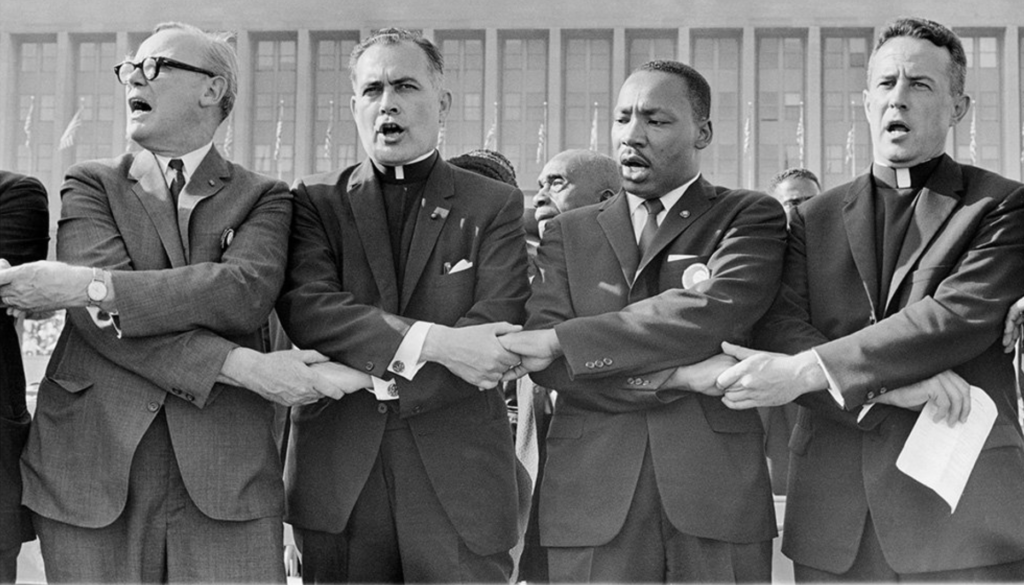

The Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, center left, holds hands with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. while singing “We Shall Overcome” during a civil rights rally at Soldier Field in Chicago on June 21, 1964. Photo courtesy of OCP Media

In the media and in our popular imagination, the religious right towers over our political landscape. So much so, in fact, that one could be forgiven for thinking that reflexive Republicanism is the only widespread expression of Christianity in politics.

The religious right’s shadow is so large that it is usually the reference point for any discussion of the religious left. Each election cycle, a spate of articles, essays and columns, mostly by white journalists, appears, inquiring why the religious left is not as important as the religious right. Is there a religious left at all?

After their party largely neglected faith outreach in 2016, the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates seem to have caught the religion bug, and to hear them talk some might think the religious left has a chance this cycle to counter the religious right’s decades-long hold on American politics.