by Fredrick Nzwili, RNS | Oct 18, 2018 | Headline News |

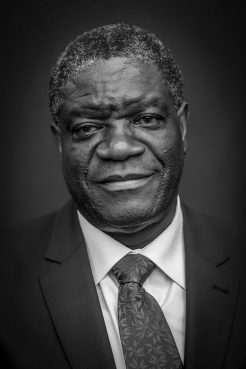

Congolese gynecologist and Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Denis Mukwege, in his office at Panzi Hospital on Feb. 6, 2013, in eastern Congo. Photo by PINAULT/VOA/Creative Commons

NAIROBI, Kenya (RNS) — At a tender age, Denis Mukwege accompanied his father, a Pentecostal church pastor, as he moved around the villages of Congo’s South Kivu Province praying for sick parishioners.

Those experiences inspired Mukwege to become a doctor — and later to found Panzi Hospital, a church-run facility in Bukavu, a community in eastern Congo. There, Mukwege has become known as the doctor who heals women suffering horrific damages after rape.

On Oct. 5, Mukwege and Nadia Murad, a young Iraqi human rights activist, won the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict in their countries.

The 63-year-old gynecologist, a Pentecostal Christian, is the medical director at Panzi Hospital, where for two decades he has treated thousands of women and girls badly mutilated after being subjected to rape.

In eastern Congo, armed men have been using rape as a weapon of war in a prolonged conflict largely centered on the control of mineral wealth. The region is rich in tantalum, a rare earth metal, along with tungsten and gold.

“I think they want to destroy the community. They rape in the presence of family members and the villagers,” Mukwege told this writer in an interview at Panzi Hospital at the peak of the violence in 2009.

“I feel bad when I see children, the same age as mine, have been raped, and they have been destroyed. They have no rectum, no sex organs, and this has been done by men who just want to destroy. This affects me as a person.”

But at the hospital, survivors of sexual violence have been finding help.

The doctor has been performing reconstructive surgery, giving them a new lease of life. And when they leave the hospital, the women are also emotionally and mentally empowered, apart from receiving financial and educational support to help rebuild their lives.

Since its founding, the hospital has treated more than 85,000 women and girls with complex gynecological injuries. More than 50,000 are survivors of sexual violence.

Rape survivors learn practical skills while recovering at Panzi Hospital in Bukavu in eastern Congo in 2009. RNS photo by Fredrick Nzwili

The doctor has dedicated his award to women all over the world harmed by conflict and suffering violence every day.

“Indeed, this honor is an inspiration because it shows that the world is … paying attention to the tragedy of rape and sexual violence and that the women and children who have suffered far too long are not being ignored,” Mukwege said in a statement released soon after he learned of the prize. He was in the midst of a surgery when the announcement was made.

“This Nobel Prize reflects this recognition of the suffering and the need for just reparation for female victims of rape and sexual violence in countries across the world and all continents.”

According to the doctor, the Nobel Prize will have real meaning only if it helps mobilize people to change the situation for victims of armed conflict. For years, he has advocated for the reclassification of sexual assaults, gang rapes and sexual mutilations by soldiers as war crimes. He has taken this advocacy to the United Nations, the U.N. Security Council and other international organizations.

Since the beginning, his work has been inspired by his faith.

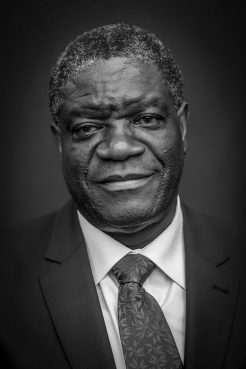

Dr. Denis Mukwege in November 2014. Photo © Claude Truong-Ngoc/Creative Commons

In 1999, he founded the Panzi Hospital with support from the Communauté des Eglises de Pentecôte en Afrique Centrale. CEPAC, which was founded in 1921 by Swedish Pentecostals, is one of the largest Pentecostal groups in Congo. The church manages the hospital.

Although the hospital’s main focus is to offer medical and psychological treatment to survivors of sexual violence, it runs other projects too, including a training for medical staff on repair of fistulas, an HIV and AIDS program and a nutrition one, among others.

In Congo, CEPAC has an estimated membership of about 800,000 in more than 700 congregations concentrated in the eastern parts. The church runs more than 1,000 schools and about 160 health centers and implements several humanitarian and development projects in the war-torn region.

“We (churches) see Dr. Mukwege as a true blessing and a gift from God to CEPAC and Congo,” the Rev. Mateso Muke, spokesman of the 8th Community of Pentecostal Churches in Central Africa, said in a telephone interview Thursday (Oct. 18). “It’s a rare commitment to be helping ordinary citizens badly affected by violence, especially women. He is a true patriot.

“The award has given a good image to CEPAC and its work. Through him Congo and Africa have got a true defender of peace,” added Muke.

Other churches in eastern Congo have welcomed news of Mukwege’s Nobel Prize, saying it will boost the war against sexual violence in the region.

“We are very happy,” Bishop Josue’ Bulambo Lembelembe of the Church of Christ in Congo said. “This is also great recognition for the work of the church.”

Roman Catholic Archbishop Marcel Utembi Tapa of Kisangani said the award was an encouragement to all to oppose any forms of violence against women.

“The criminal use of rape as a weapon of war is a serious violation of life and respect for all human beings, especially women,” said Utembi.

by Christine A. Scheller | Dec 6, 2011 | Feature |

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book, Black Fire: 100 Years of African American Pentecostalism, the Regent University visiting professor traces those roots back to the Azusa Street Revival and beyond. Alexander was so influenced by what she learned that she’s spearheading the launch of William Seymour College in Washington, D.C., to continue the progressive Pentecostal legacy of one of the movement’s most important founders. Our interview with Alexander has been edited for length and clarity.

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book, Black Fire: 100 Years of African American Pentecostalism, the Regent University visiting professor traces those roots back to the Azusa Street Revival and beyond. Alexander was so influenced by what she learned that she’s spearheading the launch of William Seymour College in Washington, D.C., to continue the progressive Pentecostal legacy of one of the movement’s most important founders. Our interview with Alexander has been edited for length and clarity.

URBAN FAITH: I was introduced to Rev. William Seymour through your book. What was his significance in Pentecostal history and why was it ignored for so long?

ESTRELDA Y. ALEXANDER: I grew up Pentecostal but don’t remember hearing about Seymour until I went to seminary. In my church history class, as they began to talk about the history of Pentecostalism, they mentioned this person who led this major revival, and I’m sitting in class going, “I’ve never heard of him.” I would say part of it was the broad definition of Pentecostalism, which is this emphasis on speaking in tongues, and that wasn’t Seymour’s emphasis. So, even though he’s at the forefront of this revival, he’s out of step with a lot of the people who are around him. Then again, he’s black in a culture that was racist. For him to be the leader would have been problematic, and so he gets overshadowed. I think his demeanor was rather humble, so he gets overshadowed by a lot of more forceful personalities. He doesn’t try to make a name for himself and so no name is made for him. He gets shuffled off to the back of the story for 70 years, then there’s this push to reclaim him with the Civil Rights Movement. As African American scholars start to write, he’s part of the uncovering of the story of early black history in the country.

What was his role specifically in the Azusa Street Revival?

He was the pastor of the church where the revival was held, so these were his people and he stood at the forefront of that congregation. The revival unfolds under his leadership.

The revival initially began with breaking barriers of race, class, and gender, but quickly reverted to societal norms. Why?

Estrelda Alexander

They began as this multi-racial congregation, though I think it still was largely black. Certainly there were people there of every race and from all over the world, and women had prominent roles. That was unheard of in the early twentieth century. They were derided not only for their racial mixing, but also for the fact that women did play prominent roles. But within 10 years, much of that had been erased. As the denominations started to form, which they did within 10 years of the revival, they started to form along racial lines. Sociologist Max Weber talks about the routinizing of charisma, that all new religious movements start with this freedom and openness to new ways of being, but as movements crystallize, they begin to form the customary patterns of other religious movements. You see that happen over and over again. That’s not just Azusa Street; that’s a process that is pretty well documented.

Is there still more racial integration in Pentecostal churches than in the wider of body of churches?

There has been an attempt to recapture the racial openness with certain movements. There’s what we call the Memphis Miracle, an episode where the divided denominations came together and consciously made an effort to tear down some of those barriers. It’s been more or less successful. There’s still quite a bit of division. It’s not on paper. On paper, there’s this idea that we’ve all come together, but the practicality of it doesn’t always get worked out.

Some of the division was about doctrine, in particular in regard to the nature of the Trinity. Was that interconnected with the racial issues, or are those two separate things?

They’re not interconnected. There are certainly some racial overtones in the discussion, but that doctrine gets permeated throughout black and white Pentecostal bodies. One of the interesting things, though, is that one of the longest-running experiments in racial unity was within the Oneness movement, which reformulated the doctrine of the Godhead. The Pentecostal Assemblies of the World has tried very hard to remain inter-racial, and adopted specific steps making sure that when there was elections that the leadership reflected both races. If, for instance, the top person elected was white, then the second person in place would be black. It would go back and forth. It’s now predominantly a black denomination, though.

Does Pentecostal theology make it more hospitable to alternative views of the Trinity?

Oh no. In Pentecostalism there is a major divide over the nature of the Godhead, and so the break over that issue wasn’t hospitable. I was a member of a Oneness denomination for a while, but I’m a theologian, so I’ve come to a more nuanced understanding of the Godhead. But in conversations with others, the language that gets used when they talk about each other’s camps is very strong. They are quick to call each other heretics. Among scholars, we tend to be more accepting of other ways of seeing things, but within the local churches, especially among pastors, that is a real intense issue.

In the book, you say Rev. T.D. Jakes views the Godhead as “manifestations” of three personalities and that he successfully straddles theological fences. How has he been able to do that?

For a lot of the people in the pews, what they see is Jakes’ success, so they don’t even pay attention to or understand that there is a difference. You’ll see people who, if they understood what Jakes was saying, they would not accept it. I’m not saying what Jakes is saying is wrong. I think the Godhead is a mystery and anybody that says they can explain it is not telling the truth.

Continued on page 2.

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book,

Dr. Estrelda Y. Alexander grew up in the Pentecostal movement, but didn’t know much about the black roots of that movement until she was a seminary student. In her groundbreaking new book,