Mary Lou’s Sacred Jazz

Mary Lou Williams inspired Duke Ellington and a generation of future jazz legends. But it’s her sacred jazz, and journey of faith, that captivated my spirit.

Mary Lou Williams inspired Duke Ellington and a generation of future jazz legends. But it’s her sacred jazz, and journey of faith, that captivated my spirit.

The brilliant jazz pianist and composer Mary Lou Williams, who died in 1981 at age 71, was a prolific artist, writing and arranging hundreds of compositions and released dozens of recordings. Along the way, she worked with jazz giants such as Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman and served as a mentor to other seminal figures, including Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk.

Williams, who often stated that she wanted to be a force for emotional healing through her music, began focusing on faith-based compositions during the 1960s. From 1963 until 1970, she composed a number of hymns and three Mass settings that garnered attention within the American Catholic church as well as from the Vatican. Her liturgical music even inspired Ellington to write his own Sacred Concerts.

As I sit in my Manhattan apartment, I am surrounded by the spirit of Mary Lou Williams: the record cover photo from her 1978 Montreux Jazz Festival solo concert looks out from above my computer; recordings dating back to 1938 sit on a CD shelf devoted strictly to Williams’ music; and my own sheet music scores are all over the living room futon as I finish putting together a songbook to accompany my own sacred jazz recording, From This Place.

Even more important than these physical items is the recognition in my own spirit of an affinity, a sense that I am continuing in Williams’ legacy of bringing together jazz and liturgy, whether I am literally playing her compositions with my trio or playing my own pieces in a local or faraway church. Why does Mary Lou Williams matter, and how has she given so much inspiration to me?

Rather than give a complete chronological overview of Williams’ work (which has been done with great aplomb elsewhere), I’d like to briefly recount Williams’ journey of faith — her conversion to Catholicism, her liturgical music — and how my own personal journey has been influenced by this bold woman’s inspiring path.

The Roots of Conversion

In 1952, after a career that had included being principal arranger, composer, and pianist for bassist Andy Kirk’s Twelve Clouds of Joy in the late 1920s and 30s, writing big band arrangements for Goodman and Ellington, orchestral arrangements of her original pieces, and playing extended trio engagements at respected New York jazz venues, Mary Lou Williams set sail for a nine-day performance tour in England. Her nine-day tour turned into a two-year European sojourn.

In 1952, after a career that had included being principal arranger, composer, and pianist for bassist Andy Kirk’s Twelve Clouds of Joy in the late 1920s and 30s, writing big band arrangements for Goodman and Ellington, orchestral arrangements of her original pieces, and playing extended trio engagements at respected New York jazz venues, Mary Lou Williams set sail for a nine-day performance tour in England. Her nine-day tour turned into a two-year European sojourn.

Williams’ conversion to Christianity had its roots in Paris. While she had experienced many successes in her career, she also had many disappointments, both in business affairs and in her desire to take care of those less fortunate than herself (often members of her extended family). Her brilliance as a forward-thinking composer and performer belied the lack of opportunities she was afforded to record as a bandleader. Her family in Pittsburgh had the impression that Williams was a wealthy woman (and she indeed often sent money home to aid her relatives); however, Williams struggled all her life to survive financially as a jazz musician. During her sojourn in Paris, she began to feel a growing depression, a sense that music held little meaning for her.

While in Europe, one of Williams’ patrons, an American expatriate and practicing Catholic named Colonel Edward L. Brennan, introduced her to a church with a garden. It was of this place that Williams later remarked that she had “found God in a little garden in Paris.” Around this same time, she began seeking solace in prayer and in reading the Psalms. She also grew more reclusive as she questioned her career as a musician and attempted to find a way to get close to God.

Returning to the States in late 1954, Williams began withdrawing from the performing world. She did several radio and television appearances, and also recorded the important chronicle of jazz music, A Keyboard History, but turned down offers to perform in nightclubs, feeling that their environments were sinful. She continued her inward spiritual search, briefly attending Harlem’s historic Abyssinian Baptist Church before embarking on an austere diet of prayer and service that began at Our Lady of Lourdes, a Catholic church in her Harlem neighborhood. Williams reportedly made lists of up to 900 names of people she would pray for every day: she would spend hours in the church in prayer, then return home to attend to family members (who had moved in with her from Pittsburgh), some of whom had addictions to drugs. Even though she needed money, she continued to turn down performance offers.

In 1956 and ’57, Williams met two priests who proved influential in her spiritual formation and her return to public performance. Father John Crowley met Williams’ close friends Dizzy and Lorraine Gillespie while working as a missionary in Paraguay. Crowley, a jazz lover, met with Williams when he returned to the East Coast. He urged her to stop taking in musicians and family with addiction issues. He also suggested that she offer her music as a prayer for others, nudging her towards her eventual decision to re-enter the jazz scene as an active performer.

A Jesuit priest, Father Anthony Woods, was introduced to Williams by Barry Ulanov, the great jazz writer who had himself converted to Catholicism from Judaism. Woods, who was based at the large St. Ignatius Loyola Church on Park Avenue, gave catechism classes that Williams attended with Lorraine Gillespie. Woods helped Williams learn how to pray for others without writing out each name on her lengthy prayer lists. Perhaps most important, he encouraged her to return to her music. In 1957 both Williams and Gillespie were baptized and confirmed in the Catholic Church.

A Marriage of Jazz and Faith

Williams’ conversion began a ten-year period of bringing together jazz and liturgy, from 1962 to 1972. In ’62 Williams composed “Hymn for St. Martin de Porres” for the Dominican lay brother who was the first person of color to be canonized in the Catholic Church. The piece appears on the 1964 recording Black Christ of the Andes, released on Williams’ own record label, Mary Records.

In 1964 Williams convinced the Pittsburgh bishop, John J. Wright, to help sponsor the first Pittsburgh Jazz Festival. At that festival, which included Art Blakey, Thelonious Monk, Ben Webster, and others, Melba Liston arranged much of Williams’ original material (including “St. Martin de Porres” and “Praise the Lord”) for a 25-piece band.

Pittsburgh was also where Williams composed the first of her three Masses. In 1967 she was hired by Bishop Wright to teach music at Seton High School, a Catholic girls’ school in the city. Williams began writing her first Mass (simply entitled Mass) during her teaching: according to Williams, she would write eight bars at a time and then teach the new material to the students. In July of the same year, her complete Mass was performed in Pittsburgh’s St. Paul’s Cathedral with a small choir of thirteen voices and piano.

In 1968 Williams was commissioned by the New York Catholic Diocese to compose a Mass for Lent. Mass for Lenten Season was performed for six Sundays at the Church of St. Thomas the Apostle in New York in 1968. The instrumentation included saxophone, flute, guitar, piano, bass and drums (or bongos). These first two Masses have never been recorded in their entirety.

That April, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Williams composed two tribute pieces for the civil rights leader. “If You’re Around When I Meet My Day” and “I Have a Dream” were both performed by a children’s choir on Palm Sunday of 1968.

In March 1969 the Pontifical Commission on Justice and Peace commissioned Williams to write the Mass for Peace. This papal commission was an opportunity that Williams had dreamed about for years.

This third Mass, which combined jazz-rock and gospel, is the best known of the three Masses. Williams self-released the work on Mary Records and premiered Music for Peace in concert at Columbia University’s St. Paul’s Chapel in April 1970. She presented the piece in churches and schools for several years before it was performed as part of a Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York in 1975. She also expanded the Mass for Alvin Ailey, who choreographed and performed the work, now known as Mary Lou’s Mass. (See the video above to hear my interpretation of “Gloria” from Mary Lou’s Mass).

From 1977 to 1981, Williams was artist-in-residence at Duke University, where her history of jazz classes had long waiting lists — Williams’ love of educating young people made her an extremely popular teacher. She formed the Mary Lou Williams Foundation just prior to her death on May 28, 1981.

Traveling with Mary Lou

My own journey with Mary Lou Williams began two decades ago.

In 2000, Dr. Billy Taylor asked me to lead my group at the Mary Lou Williams Festival at the Kennedy Center. I was excited and felt a huge responsibility to learn about Williams — at that time, I did not yet know any of her work. I had heard Williams’ name, and knew that she had been a pioneering jazz musician who had mentored Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, and Thelonious Monk — but I had not yet listened to that much of her music.

Fortunately, I found ample resources with which to begin my research: trumpeter Dave Douglas had recently released the recording Soul on Soul, a tribute to Williams; author Linda Dahl had recently released her biography of Williams, Morning Glory; and I visited the wonderful Mary Lou Williams Collection at the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University.

The revelation about Williams’ sacred output was especially of interest to me, as I had moved from Chicago to New York in 1997 to accept a position as music director at All Angels’ Church, an Episcopal parish on the Upper West Side. While at All Angels’, I composed the beginnings of two Mass settings, Psalm settings, and new music for old hymn texts. After leaving that position in 2000 (right around the time of my Kennedy Center performance). Inspired by Williams, I realized that I had a book of music that might have a life outside of one congregation.

Like Mary Lou Williams, I began making contacts with churches when I would travel, and started presenting my sacred music in the context of worship services, something I do to this day. Like Williams, I feel passionately that jazz has much to offer the church: its life, richness, and ability to move hearts is sorely needed as part of the musical palette offered in worship music today. Like Williams, I converted to Catholicism. (I was received into the church in 2009.) While my decision to convert was not because of Williams, her courage to follow the leading of God’s Spirit — both in music and in faith — provided me with constant encouragement, comfort, and sometimes a kick in the pants to move forward.

Going back and rereading portions of Morning Glory, I resonate even more deeply with Williams’ struggles as a bandleader and composer. At times, I have felt discouragement, confusion, and loneliness as I have wrestled with where God is leading me. I have wondered why my path does not seem to be conventional. But then I look at the photo of Williams above my computer, and I’m reminded that I’m not alone. This strong, talented, sensitive, passionate woman has laid the groundwork for me and many others who follow in her wake. How could we not be emboldened by her remarkable example?

______________________________________________________________________

More Mary Lou

For additional information on the life and music of Mary Lou Williams, check out these selected resources.

Online:

• The Mary Lou Williams Collection at the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University has an online exhibit dedicated to Williams.

•The Mary Lou Williams Foundation is managed by Father Peter O’Brien, Williams’ former manager.

•Deanna Witkowski’s website features video clips of her musical seminar Moving With the Spirit: The Sacred Jazz of Mary Lou Williams.

In Print:

Historian Tammy Kernodle’s biography Soul on Soul: The Life and Music of Mary Lou Williams gives ample attention to Williams’ spiritual conversion and liturgical music. And the aforementioned Morning Glory, by Linda Dahl, is another significant biography of Williams:

On CD:

Both Mary Lou’s Mass and Mary Lou Williams Presents Black Christ of the Andes have been reissued in the last several years by Smithsonian Folkways, and are available on iTunes as well as at Amazon.

Williams’ non-liturgical recordings are also noteworthy and substantial. Two of Deanna Witkowski’s personal favorites are Live at the Cookery and Zodiac Suite. In addition, Nite Life includes a half-hour spoken commentary by Williams.

______________________________________________________________________

Related Article: A Chanteuse of Sacred Jazz

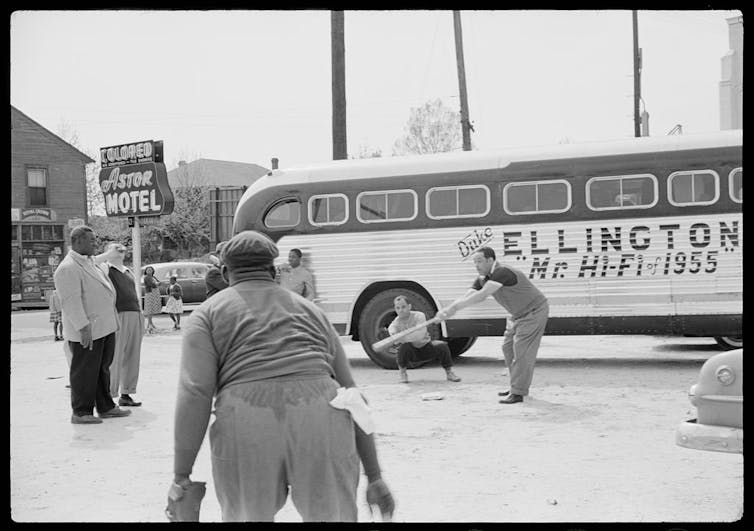

Photos from the Mary Lou Williams Foundation website.