Do the Democrats have a religion problem?

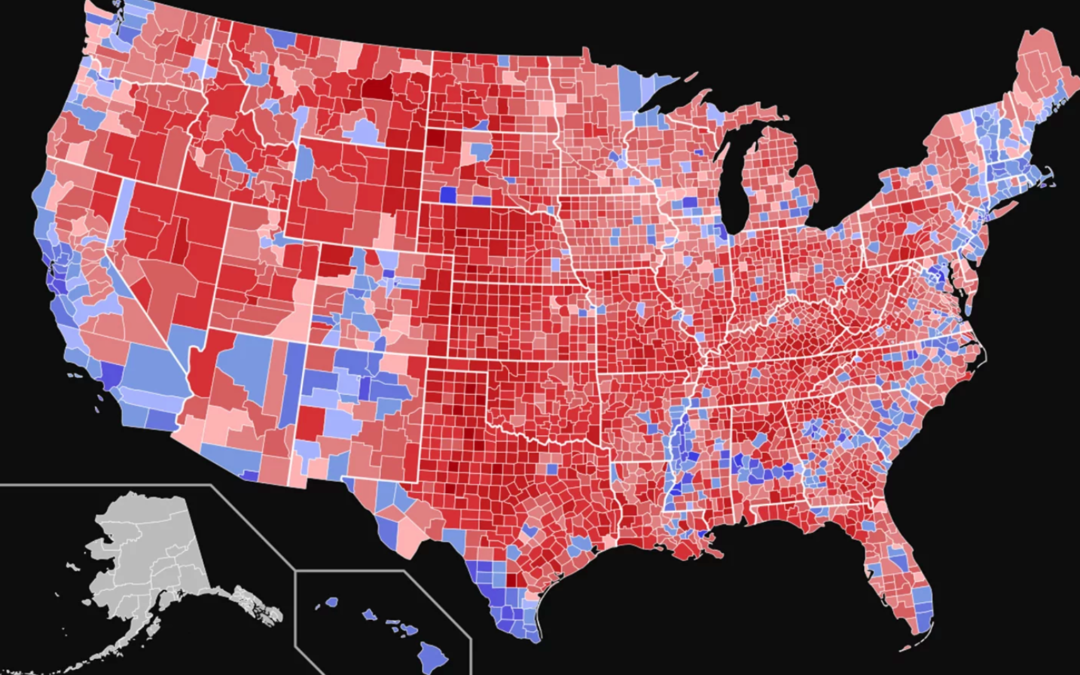

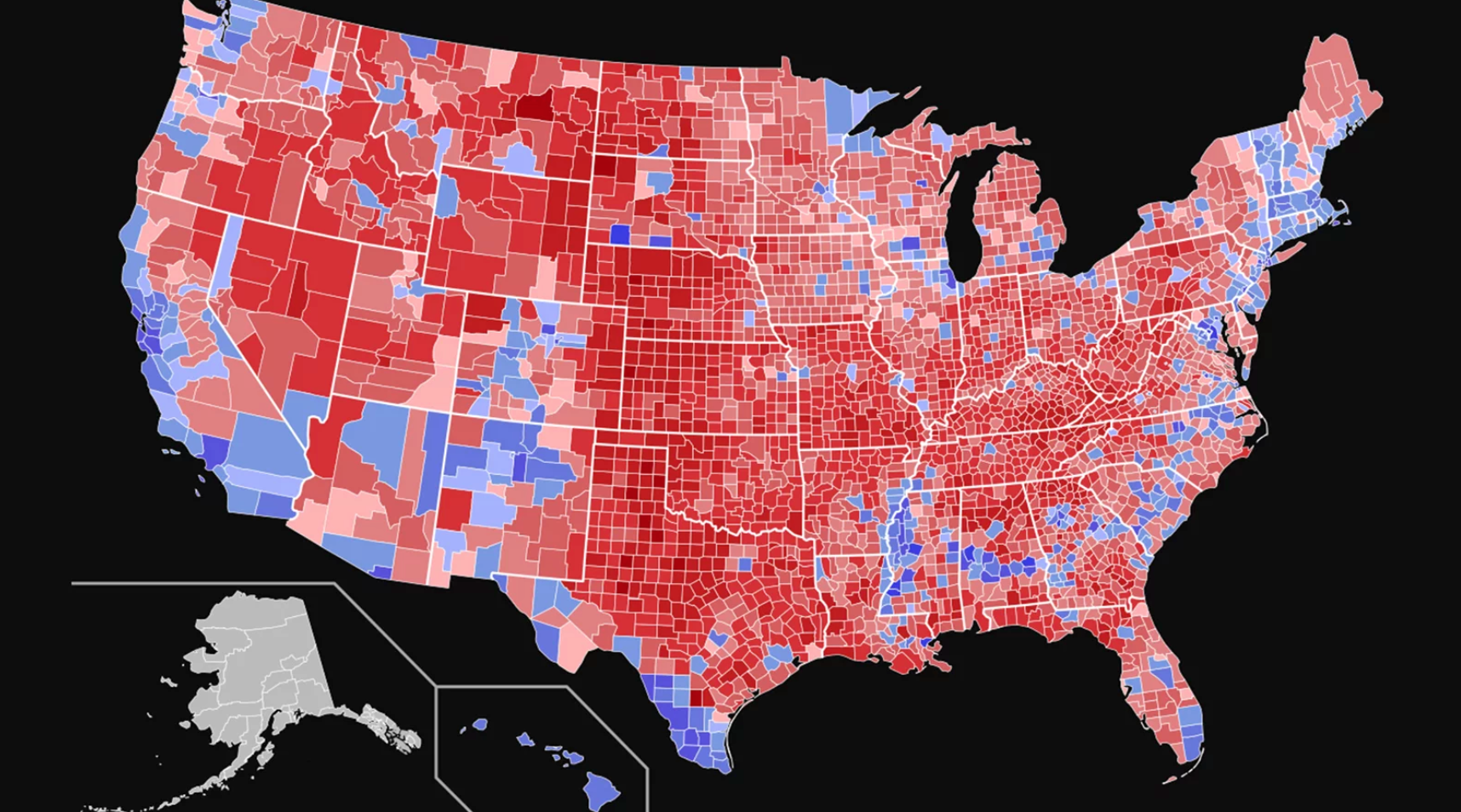

Nationwide map of 2016 U.S. presidential election results shaded by vote share in each county. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

For the past couple of decades, the question, “Do the Democrats have a religion problem?” has seemed to answer itself. Of course, they do!

The basis for this conventional wisdom is what came to be known in the early 2000s as the God gap. Measured in terms of the preference for Republicans among those who say they attend worship at least once a week, the gap grew from 5 percentage points to 20 between 1990 and 2000. That is to say, by the 2000 election, weekly worshippers (of all spiritual persuasions) were voting for Republican presidential and congressional candidates by a margin of 60% to 40%.

It’s not so easy to say why this happened when it did. President Bill Clinton was a regular churchgoer, a Southern Baptist who believed abortion should be “safe, legal and rare,” opposed same-sex marriage and instituted the “don’t ask, don’t tell” LGBT policy in the military. But then there was the Lewinsky scandal and, thanks to serious grassroots politicking by Pat Robertson’s Christian Coalition, the coming of age of the religious right.

Democratic presidential candidates participate during the Democratic primary debate hosted by NBC News at the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts on June 26, 2019, in Miami. (AP Photo/Wilfredo Lee)

However it is explained, the 20-point gap persisted in the 2002 midterms, and by 2004 Democrats were beginning to worry. In the keynote address that launched his national career at the Democratic convention that year, Barack Obama famously pointed out that “we worship an awesome God in the blue states.” Which was nothing if not an acknowledgment that the blue states had come to be seen as dominated by the godless.

Obama’s claim notwithstanding, Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry didn’t handle religion very well. Albeit a pretty observant Catholic, he was pro-choice and, like most New England politicians, averse to speaking about his faith on the campaign trail.

After Kerry went down to defeat, the party chairmanship fell to Howard Dean, another New England pol with a secular style. But Dean, determined to change the party’s image, recruited a black Pentecostal woman to do religious outreach and rounded up candidates around the country capable of engaging religiously. Lo and behold, in 2006 the Democrats captured control of both houses of Congress, as the gap shrank to 12 points.

Two years later, two books by prominent journalists chronicled the Democrats’ apparent revival: “The Party Faithful: How and Why Democrats Are Closing the God Gap” by Time magazine’s Amy Sullivan and “Souled Out: Reclaiming Faith and Politics After the Religious Right” by The Washington Post’s E.J. Dionne.

President Barack Obama, first lady Michelle Obama and daughters Malia and Sasha attend Easter church service at Shiloh Baptist Church in Washington, D.C., on April 24, 2011. Official White House Photo/Pete Souza/Creative Commons

Indeed, the 2008 election cycle saw a lot of religion on the Democratic side. During the primaries, Obama and Hillary Clinton competed in religious outreach. During the general election campaign, the prominent evangelical pastor Rick Warren conducted high-profile interviews of Obama and GOP nominee John McCain. But religion proved to be more of a burden than a balm for Obama as president, and in 2012, it more or less disappeared from his presidential campaign.

At the presidential level, none of this mattered. Regardless of the degree of attentiveness to religion by the Democratic nominee, the 20-point God gap persisted.

Here it’s important to recognize that the gap is mostly about white Christians — Catholics, mainline Protestants, evangelicals, Greek Orthodox and Mormons. Among non-Christians, only Orthodox Jews go Republican. Among people of color the only group that doesn’t vote strongly Democratic are Latino evangelicals, who divide equally between Democrats and Republicans.

The gap is also more about frequently attending men than frequently attending women. The former vote strongly Republican; the latter have tended to be closely divided between Republicans and Democrats.

And then there are the nones, who since 1990 have risen from under 10% to a quarter of the U.S. population. They make up a large portion of what can be called the godless gap — the portion of the electorate that says it goes to worship infrequently if at all, and that votes strongly Democratic.

I suspect that one of the reasons we’re not hearing much from Democratic operatives about dealing with the God gap in this election cycle is because they think it matters less and less. Sure, frequent attenders continue to vote Republican, but there are fewer and fewer of them — and more and more nones.

President Donald Trump speaks with reporters before departing on Marine One on the South Lawn of the White House in Washington on Aug. 21, 2019. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

Consider what’s happened to the prime antagonists in the culture wars, white evangelicals and nones, in the crucial swing states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. According to PRRI’s American Values Atlas, as of 2014 white evangelicals in Pennsylvania were at 18% and nones were at 19%. In 2018 white evangelicals had dropped to 17% and nones had risen to 23% — for a 6-point swing. Comparable swings took place in the other states as well: 7 points in Ohio, 5 points in Michigan, 5 points in Wisconsin and 6 points in Minnesota.

So why bother with religious outreach?

For one thing, white evangelicals punch above their weight when it comes to voting, and nones punch below theirs. For another, there’s a real opportunity to pick up votes among women who are frequent churchgoers.

The gender gap — women’s proclivity to vote Democratic — tied its high-water mark of 11 percentage points in the last presidential election, and in last year’s congressional races reached an all-time high of 19 points. At the moment, while men are disapproving of President Donald Trump’s job performance by a few percentage points, women are disapproving by close to 20.

If I were advising the Democrats on how to deal with the God gap, I’d say attack the hard-line anti-abortion laws being passed around the country while embracing the old Clintonian “safe, legal and rare” mantra. I’d emphasize the Trump administration’s assault on the Affordable Care Act, up to and including its facilitation of exemptions from the contraception mandate.

And I’d say do something else: Make the climate crisis the pro-life issue of our era. It’s about our children’s lives, and the lives of their children, and all the children who will ever live on Earth. With time running out and a president who has set his face against even acknowledging its existence, it is the political imperative of the moment.

It is also the spiritual challenge of our time. If the Democrats can’t manage to take it up, they really do have a religion problem.