How a courtroom ritual of forgiveness absolves white America

Botham Jean’s younger brother Brandt Jean hugs convicted murderer and former Dallas Police Officer Amber Guyger after delivering his impact statement to her after she was sentenced to 10 years in jail, on Oct. 2, 2019, in Dallas. Guyger shot and killed Botham Jean, an unarmed 26-year-old neighbor in his own apartment last year. She told police she thought his apartment was her own and that he was an intruder. (Tom Fox/The Dallas Morning News via AP, Pool)

RELATED: A TEST OF FAITH: KEY WITNESS IN GUYGER TRIAL DEAD

Last week, fired Dallas police officer Amber R. Guyger, who is white, received a sentence of 10 years in prison for the murder of an unarmed black man, Botham Shem Jean.

While the sentence of 10 years for Jean’s murder certainly didn’t sit well with many, the other events of the courtroom are what have become the subjects of discussion — the words of grace, forgiveness, love and well-wishes offered by Jean’s younger brother to Guyger, capped off by a warm embrace. And if that were not enough, Judge Tammy Kemp, also an African American, added grace upon grace by going to her office to retrieve a Bible. After handing it to Guyger, the judge, too, embraced Guyger tearfully and warmly.

This scene of grace, forgiveness and reconciliation operates almost like a ritual. We saw it in 2015 when relatives of the nine victims murdered by Dylann Roof in the shooting inside an AME church in Charleston, South Carolina, told Roof “I forgive you.” We saw it again when then-President Barack Obama eulogized Pastor Clementa Pinckney, one of those killed by Roof in that Charleston church, by singing “Amazing Grace How Sweet the Sound …”

The show of grace and forgiveness toward Guyger, like those before it, requires that we ask some hard questions. What if “grace” and “forgiveness” and their compulsory racialized performance are part of what makes this anti-black world keep on ticking? What if grace and forgiveness work in the interest of anti-blackness? And finally, what if grace and forgiveness are part of what must be refused in order to bring to an end an anti-black and brown world?

I know these are profane questions for a society that holds up forgiveness as hallowed virtues. But I raise them not to cast judgment on Jean’s younger brother. The Jean family is grieving. They are in a process of healing in the wake of violence and irreparable loss. My questioning of the virtue of forgiveness and grace in civil society does not begin with the individual.

Rather, I raise these questions to get at how America is structured through race.

President Barack Obama leads mourners in singing the song “Amazing Grace” as he delivers a eulogy in honor of the Rev. Clementa Pinckney during funeral services for Pinckney in Charleston, S.C., on June 26, 2015. Pinckney was one of nine victims of a mass shooting at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Photo by Brian Snyder/Reuters

That is, in asking about the value of forgiveness and grace within the American social and political structure, I am asking about how the anti-blackness of American society works through religion-like rituals and liturgies of grace and forgiveness. I’m interested in how grace and forgiveness function publicly, how they script roles around blackness and death within a society organized around whiteness as the sign of proper life, or the life that is properly human. In this context, police violence and forgiveness rituals work to secure the common good and civil society. They work to secure America as a project of religion. Such religion may be thought of as “the religion of whiteness.”

Sociologist Robert Bellah coined the phrase “American civil religion” to explain how a secular nation maintains a religious dimension that suffuses public culture, from the political realm to civil society itself. That religious dimension has embedded within it beliefs, symbols, and ritual practices — the most well-known being the inauguration of U.S. presidents.

But Bellah’s concern was not just with the history of American religious belief, symbols and rituals. He came to his insight about the working of American civil religion in a moment when the American fabric was being torn by internal strife. It’s as if through his work as a sociologist Bellah was channeling the racial melancholy of a nation in fear and despair. The moment of crisis that he was trying to make sense of was the violence against black life and the protest movements of the 1960s.

Bellah’s idea was that the belief in and commitment to the sacred ideal of equal rights to all humans as the natural law guiding the American project is what America has always drawn on. He makes a case that the Founding Fathers in their exodus from the Old World to the new drew from the reservoir of this civil religion to found the nation. Later in America’s history, Abraham Lincoln, as a kind of savior, drew from the civil religion reservoir as well, though in his case, it was to preserve a nation in the internecine distress of the Civil War.

Notwithstanding Bellah’s great insight about the operations of American civil religion, what he nonetheless failed to grapple with was the degree to which America as a religious project rooted in the higher ideal or the natural law of human equality and freedom for all rested on an inequality within the ranks of the human ideal of freedom.

Bellah failed to address how America, as a project guided by the ideal of human freedom and equality, was predicated on settler colonial genocide and the ongoing use of black lives as property to rework stolen land and to build the national treasury. Within this structure of violence and death, blackness cannot matter for itself but only for its usefulness. In short, Bellah did not account for anti-blackness, which is not America’s original sin but its DNA.

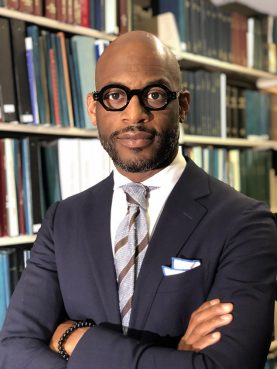

J. Kameron Carter. Courtesy photo

It is within this framework that the sacredness, sanctity and compulsory rituals of forgiveness must be understood. American religion needs black (and native) forgiveness in order to keep the national fantasy of civil society, which is anti-black, alive. After racial crisis and distress, American religion turns to rituals of forgiveness and grace carried out by those structurally positioned as black to re-cohere itself around its ideals of being the beacon of human equality and freedom. In fact, the rituals of forgiveness can be thought of as structural performances of the ideal made visible for an instant. These rituals of courtroom forgiveness display the “rightness” and sacredness of America as a project, confessed, as it were, by those who suffer under that project.

Again, what I am dealing with here is the American racial structure, not individuals. I’m dealing with why, within the religion of whiteness, whiteness needs black forgiveness to maintain itself. Black forgiveness is part of the ritual work of absolving or extending salvation to America. It is part of the work of re-cohering or saving whiteness in a moment of crisis. Should such black forgiveness be withheld, whiteness or the American religious project would face a potential collapse. It might suffer a “white out,” a possible end of the world or an end of its world.

But could the end of the world, a white out, be an alternative understanding of forgiveness, perhaps even an alternative religious orientation? Can there be a forgiveness that does not absolve guilt but brings the anti-black world to an end? Could there be a poetics of forgiveness that pressures forgiveness as we know it? Could there be a forgiveness that ends forgiveness, a forgiveness at the end of the world? Let’s hope so.

(J. Kameron Carter is a professor of religious studies at Indiana University. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)