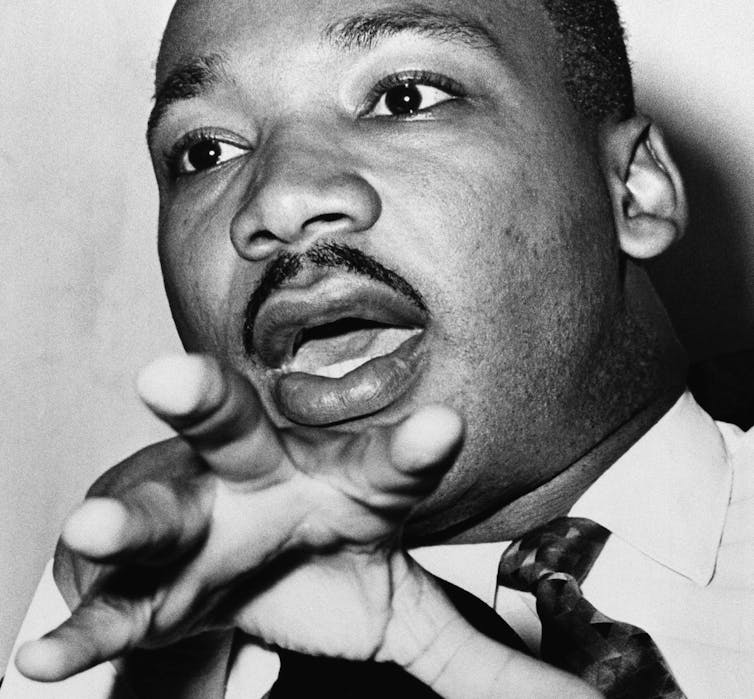

AP Photo

For years, Martin Luther King Jr. and poet Langston Hughes maintained a friendship, exchanging letters and favors and even traveling to Nigeria together in 1960.

In 1956, King recited Hughes’ poem “Mother to Son” from the pulpit to honor his wife Coretta, who was celebrating her first Mother’s Day. That same year, Hughes wrote a poem about Dr. King and the bus boycott titled “Brotherly Love.” At the time, Hughes was much more famous than King, who was honored to have become a subject for the poet.

Video Courtesy of Giovanni O’Neil

But during the most turbulent years of the civil rights movement, Dr. King never publicly uttered the poet’s name. Nor did the reverend overtly invoke the poet’s words.

You would think that King would be eager to do so; Hughes was one of the Harlem Renaissance’s leading poets, a master with words whose verses inspired millions of readers across the globe.

However, Hughes was also suspected of being a communist sympathizer. In March of 1953, he was even called to testify before Joseph McCarthy during the Red Scare.

Meanwhile, King’s opponents were starting to make similar charges of communism against him and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference, accusing the group of being a communist front. The red-baiting ended up serving as some of the most effective attacks against King and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

It forced King to distance his organization from men with similar reputations – Bayard Rustin, Jack O’Dell and even his closest adviser, Stanley Levison.

It also meant he needed to sever any overt ties to Hughes.

But my research has found traces of Hughes’ poetry in King’s speeches and sermons. While King might not have been able to invoke Hughes’ name, he was nonetheless able to ensure that Hughes’ words would be broadcast to millions of Americans.

Beating back the red-baiters

In the 1930s, Hughes earned a subversive reputation by writing several radical poems. In them, he criticized capitalism, called for worker’s to rise up in revolution and claimed racism was virtually absent in communist countries such as the U.S.S.R.

By 1940, he had attracted the attention of the FBI. Agents would sneak into his readings, and J. Edgar Hoover derided Hughes’ poem “Goodbye Christ” in circulars he sent out in 1947.

Red-baiting also fractured black political and social organizations. For example, Bayard Rustin was forced to resign from the SCLC after African-American Congressman Adam Clayton Powell threatened to expose Rustin’s homosexuality and his past association with the Communist Party USA.

Library of Congress

As the leading figure in the civil rights movement, King had to toe a delicate line. Because he needed to retain popular support – as well as be able to work with the Kennedy and Johnson administrations – there could be no question about where he stood on the issue of communism.

So King needed to be shrewd about invoking Hughes’ poetry. Nonetheless, I’ve identified traces of no fewer than seven of Langston Hughes’ poems in King’s speeches and sermons.

In 1959, the play “A Raisin in the Sun” premiered to rave reviews and huge audiences. Its title was inspired by Hughes’ poem “Harlem.”

“What happens to a dream deferred?” Hughes writes. “Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? … Or does it explode?”

Just three weeks after the premiere of “A Raisin in the Sun,” King delivered one of his most personal sermons, giving it a title – “Shattered Dreams” – that echoed Hughes’ imagery.

“Is there any one of us,” King booms in the sermon, “who has not faced the agony of blasted hopes and shattered dreams?” He’d more directly evoke Hughes in a later speech, in which he would say, “I am personally the victim of deferred dreams.”

Hughes’ words would also become a rallying cry during the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

During the grind of the year-long boycott, King spurred activists on by pulling from “Mother to Son.”

“Life for none of us has been a crystal stair,” King proclaimed at the Holt Street Baptist Church, “but we must keep moving.” (“Well, son, I’ll tell you / Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair,” Hughes wrote. “But all the time / I’se been a-climbin’ on.”)

Did Hughes inspire the dream?

King’s best-known speech is “I Have a Dream,” which he delivered during the 1963 March on Washington.

Nine months before the famous march, King gave the earliest known delivery of the “I Have a Dream” speech in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. (We can also now finally hear this connection after the reel-to-reel tape of King’s First Dream was recently discovered.)

But the roots of “I Have a Dream” go back even further. On Aug. 11, 1956, King delivered a speech titled “The Birth of a New Age.” Many King scholars consider this address – which talked about King’s vision for a new world – the thematic precursor to his “I Have a Dream” speech.

In this speech, I recognized what others had missed: King had subtly ended his speech by rewriting Langston Hughes’ “I Dream a World.”

A world I dream where black or white,

Whatever race you be,

Will share the bounties of the earth

And every man is free.

It is impossible not to notice the parallels in what would become “I Have a Dream”: I have a dream that one day … little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers.

![]() King spoke truth to power, and part of that strategy involved riffing or sampling Hughes’ words. By channeling Hughes’ voice, he was able to elevate the subversive words of a poet that the powerful thought they had silenced.

King spoke truth to power, and part of that strategy involved riffing or sampling Hughes’ words. By channeling Hughes’ voice, he was able to elevate the subversive words of a poet that the powerful thought they had silenced.

Jason Miller, Professor of English, North Carolina State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.