Return looted artifacts made by brilliant African cultures

Shutterstock.

European museums are under mounting pressure to return the irreplaceable artifacts plundered during colonial times. As an archaeologist who works in Africa, this debate has a very real impact on my research. I benefit from the convenience of access provided by Western museums while being struck by the ethical quandary of how they were taken there by illegal means, and by guilt that my colleagues throughout Africa may not have the resources to see material from their own country, which is kept thousands of miles away.

Now, a report commissioned by the French president, Emmanuel Macron, has recommended that art plundered from sub-Saharan Africa during the colonial era should be returned through permanent restitution.

The 108-page study, written by French art historian Bénédicte Savoy and Senegalese writer and economist Felwine Sarr, speaks of the “theft, looting, despoilment, trickery and forced consent” by which colonial powers acquired these materials. The call for “restitution” echoes the widely accepted approach which seeks to return looted Nazi art to its rightful owners.

The record of colonial powers in African countries was frankly disgusting. Colonial rule was imposed by the barrel of the gun, with military campaigns waged on the flimsiest excuses. The Benin expedition of 1897 was a punitive attack on the ancient kingdom of Benin, famous not only for its huge city and ramparts but its extraordinary cast bronze and brass plaques and statues.

Wikimedia Commons.

The city was burnt down, and the British Admiralty auctioned the booty – more than 2,000 artworks – to “pay” for the expedition. The British Museum got around 40% of the haul.

None of the artifacts stayed in Africa – they’re now scattered in museums and private collections around the world.

The 1867 British expedition to the ancient kingdom of Abyssinia – which never fully acceded to colonial control – was mounted to ostensibly free missionaries and government agents detained by the emperor Tewodros II. It culminated in the Battle of Magdala, and the looting of priceless manuscripts, paintings, and artifacts from the Ethiopian church, which reputedly needed 15 elephants and 200 mules to carry them all away. Most ended up in the British Library, the British Museum, and the V&A, where they remain today.

Bought, stolen, destroyed

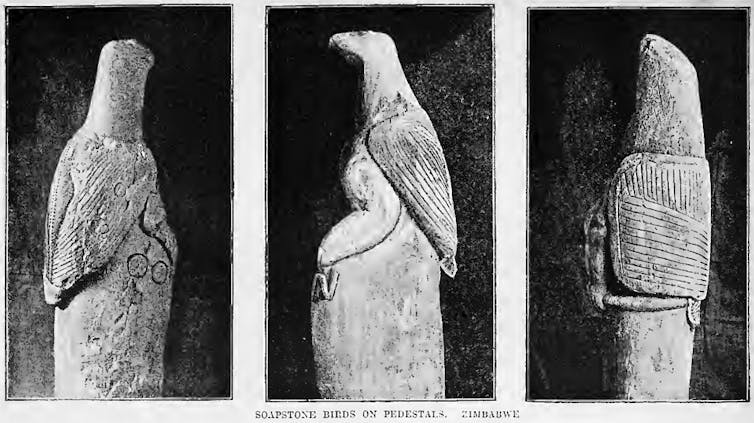

Other African treasures were also taken without question. The famous ruins of Great Zimbabwe were subject to numerous digs by associates of British businessman Cecil Rhodes – who set up the Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd in 1895 to loot more than 40 sites of their gold – and much of the archaeology on the site was destroyed. The iconic soapstone birds were returned to Zimbabwe from South Africa in 1981, but many items still remain in Western museums.

Wikimedia Commons.

While these are the most famous cases, the majority of African objects in Western Museums were collected by adventurers, administrators, traders, and settlers, with little thought as to the legality of ownership. Even if they were bought from their local owners, it was often for a pittance, and there were few controls to limit their export. Archaeological relics, such as inscriptions or grave-markers, were simply collected and taken away. Such activities continued well into the 20th century.

Making them safe

The argument is often advanced that by coming to the West, these objects were preserved for posterity – if they were left in Africa they simply would have rotted away. This is a specious argument, rooted in racist attitudes that somehow indigenous people can’t be trusted to curate their own cultural heritage. It is also a product of the corrosive impact of colonialism.

Colonial powers had a patchy record of setting up museums to preserve these objects locally. While impressive national museums were sometimes built in colonial capitals, they were later starved of funding or expertise. After African countries achieved independence, these museums were low on the priority list for national funding and overseas aid and development, while regional museums were virtually neglected.

Nowadays, many museums on the African continent lie semi-derelict, with no climate control, poorly trained staff and little security. There are numerous examples of theft or lost collections. No wonder Western museums are reluctant to return their collections.

If collections are to be returned, the West needs to take some responsibility for this state of affairs and invest in the African museums and their staff. There have been some attempts to do this, but the task is huge. It is not enough to send the contentious art and objects back to an uncertain future – there must be a plan to rebuild Africa’s crumbling museum infrastructure, supported by effective partnerships and real money.

The rightful owners

Sheep, CC BY-NC-ND

Will the Musée du quai Branly, that great treasure house of world ethnography in Paris, which holds more than 70,000 objects from Africa, be emptied of its contents? Or the massive new Humboldt Forum – a Prussian Castle rebuilt at great cost to house ethnographic artifacts in Berlin which opens early in 2019 – be shorn of its African collections? There are already fears at the British Museum that a very effective campaign may lead to the return of its Rapu Nui Moai statues to Easter Island.

This year is the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Magdala, and the V&A Museum has entered into worthy discussions to return its treasures to Ethiopia. But there are reports this would be on the basis of a long-term loan, and conditional on the Ethiopian government withdrawing its claim for restitution of the plundered objects. The Prussian Foundation in Berlin entered into a similar agreement, unwilling to cede ownership of a tiny fragment of soapstone bird to the Zimbabwe Government in 2000.

The report by Savoy and Sarr offers hope that such deals could become a thing of the past and that Africa’s rich cultural heritage can be returned, restituted and restored to the brilliant cultures that made it.![]()

Mark Horton, Professor in Archaeology, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.